Faith Ringgold began writing her life story in the summer of 1963. Resistance was fomenting. Earlier that year James Baldwin had published The Fire Next Time, condemning the nation’s brutal enshrinement of racial inequality, and in the South civil rights demonstrators were protesting segregation, spurring Martin Luther King Jr. to lead the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom that August. Ringgold, an artist, mother, and public school teacher, would later reflect that the events of that year inspired her to “create my own vision of the black experience we were witnessing”:

Baldwin understood, I felt, the disparity between black and white people as well as anyone; but I had something to add—the visual depiction of the way we are and look. I wanted my painting to express this moment I knew was history. I wanted to give my woman’s point of view to this period.

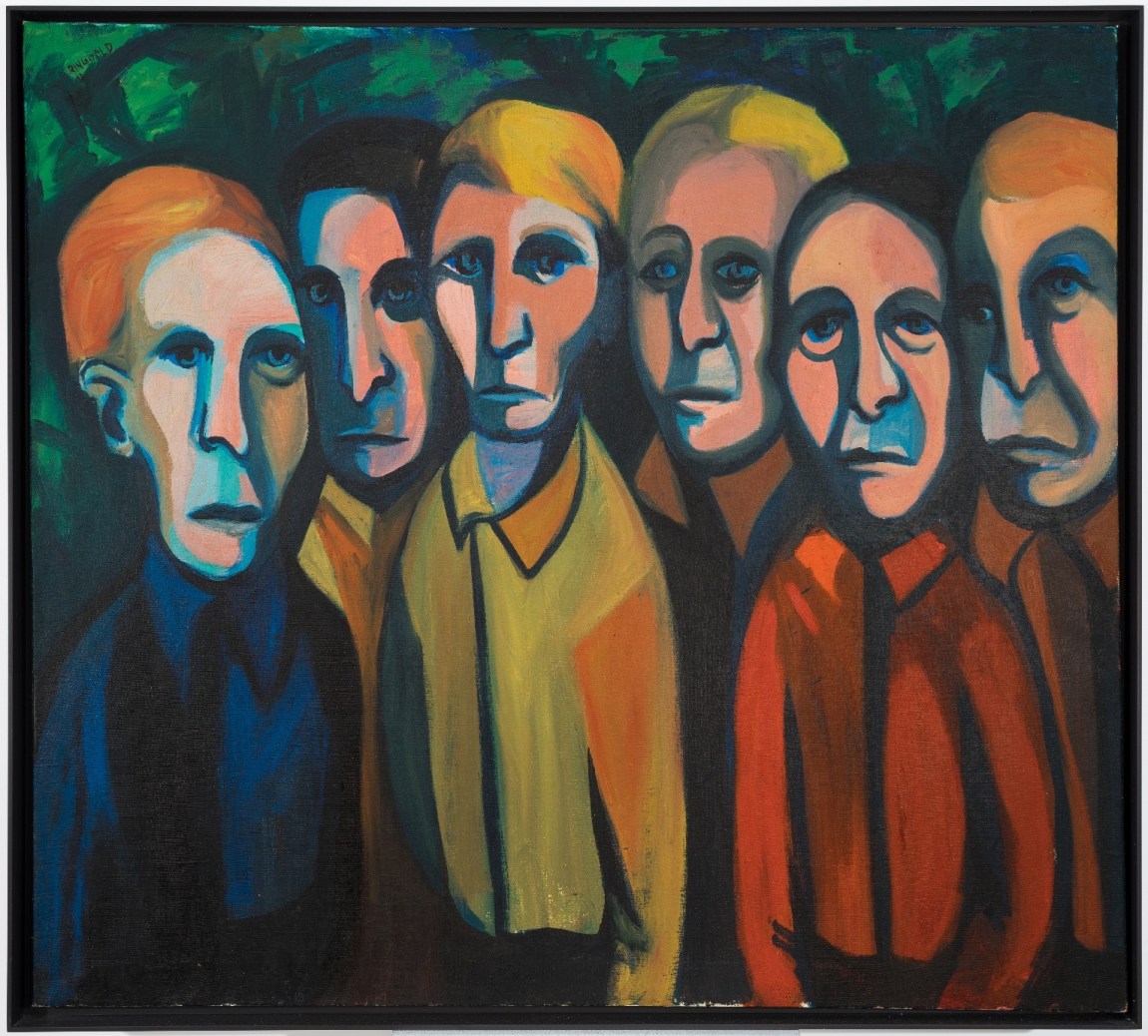

At the time Ringgold was mostly painting abstract landscapes, but the political urgency of the civil rights movement radically reshaped her style. She began crowding her paintings with Black and white figures, using the flat edge of her palette knife to create clean, harsh outlines, giving them a nearly cartoonish mien in a style she termed “Super Realism,” which complemented the work’s stark, confrontational subject matter. It was her way of making explicit the violence against the movement’s Black participants. In Neighbors (1963), a white family is pitched against a dark treescape, meeting the viewer’s gaze with deadpan expressions. For Members Only, from the same year, depicts a tight group of six white men whose long, forlorn faces are similarly chilling. These works supply an affective complement to the realities of desegregation, a gradual process met at every level by the stubborn resistance of white Americans. Ringgold constructed the images from childhood memories of racist harassment and her awareness of the political realities faced by Black people in her community. Eventually she called the series American People.

That series gives its name to Ringgold’s first major retrospective, currently on view at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. Covering nearly six decades of her incisive work in painting, graphic art, soft sculpture, and textiles, including the quilts for which she is perhaps best known, American People is both timely and overdue. At ninety-two, Ringgold has long been a beloved educator and children’s author and a pioneering activist for racial and gender equity both within and beyond the art world. This survey, which traveled from the New Museum in New York, traces Ringgold’s career trajectory, catalogs her diverse accomplishments, and emphasizes her formalist rigor.

*

As a child in Harlem, Ringgold was encouraged to explore her artistic talents by her mother, the successful fashion designer Willi Posey. In 1940 the family moved to Sugar Hill, populated since the Harlem Renaissance by artists, writers, politicians, and other members of the Black intelligentsia. A brief marriage to a jazz musician after high school and the birth of two daughters appeared to briefly derail Ringgold’s dreams of an artistic career, but following her divorce she graduated from the City College of New York with a degree in fine art and began teaching in the city’s public schools.

Summers spent painting serene scenes in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and a formative trip to France and Italy in 1961 gave Ringgold firsthand experience with the Western art historical canon, but she had little guidance and few connections in the commercial art world, which was then still dominated by white male artists and gallerists. Though artists such as Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis had made some inroads into this vaunted circle, few Black women were included in major exhibitions, and Ringgold faced rejection amongst her peers as she struggled to come into her own.

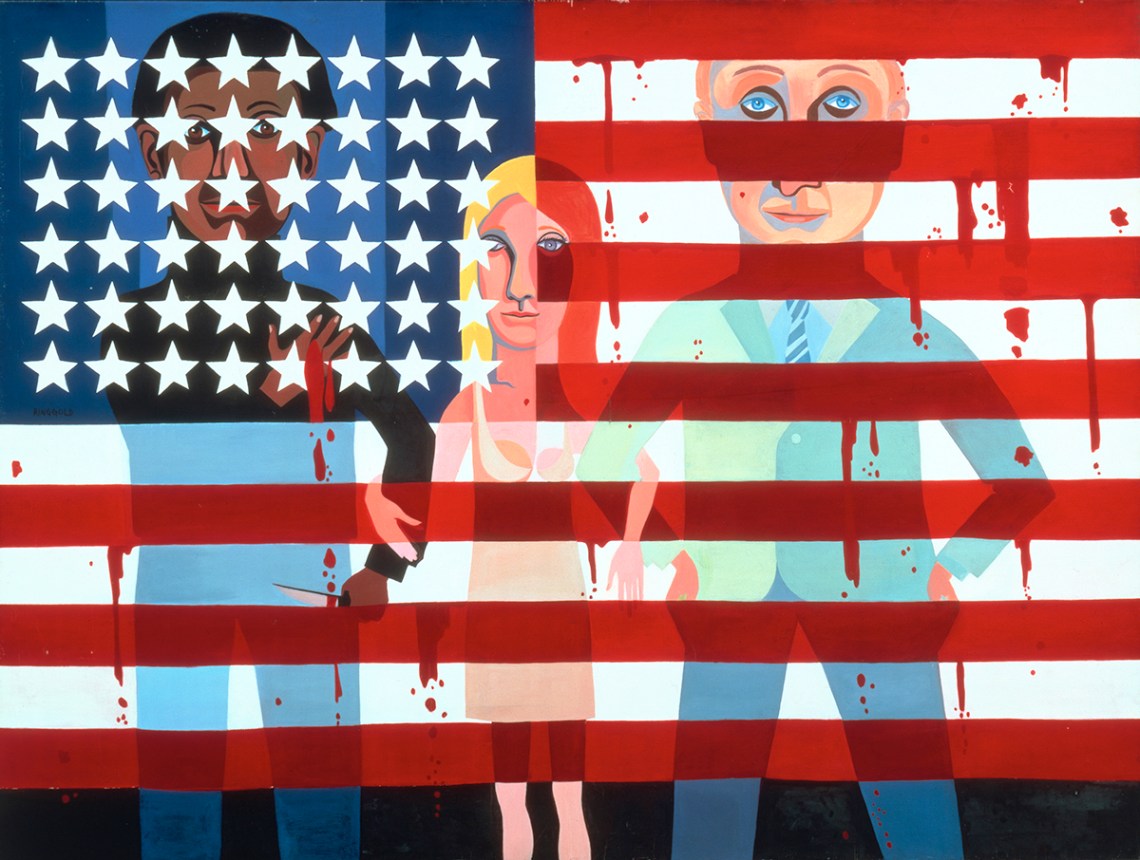

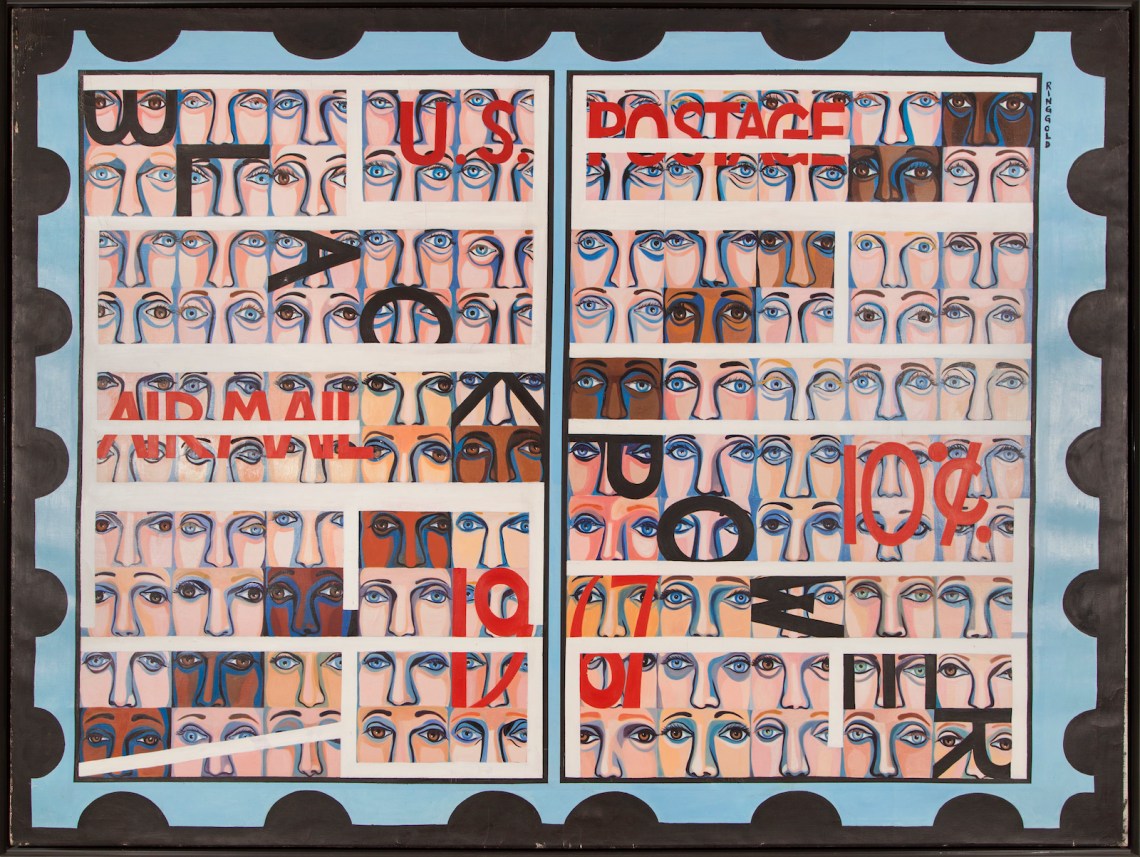

Her turn to realist facture and biting social critique in the summer of 1963 marked a decisive shift in Ringgold’s style, but it wasn’t until 1967 that she started gaining traction in the art world. That December she had her first solo show, at the cooperatively run Spectrum Gallery on West 57th Street. For the exhibition, she completed American People with three large-scale paintings that demonstrate her canny awareness—and defiance—of painting’s history and formal conventions. Two of the most striking, The Flag is Bleeding and U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, are on prominent display at the de Young. (A third, Die—based on Picasso’s Guernica and depicting a blood-soaked fracas of men, women, and children in the aftermath of a shooting—is absent from this exhibition, but made headlines when it was rehung in the same gallery as Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon at MoMA in 2019.) The exhibition was well attended by the luminaries of the Black Arts Movement, including Bearden and Lewis, and reviews praised Ringgold’s strategic depiction of violence and handling of paint—all leading to her first major sales.

Advertisement

The Flag is Bleeding was partly inspired by the critiques of American symbology mounted by Jasper Johns in his flag paintings from the 1950s, which Ringgold felt presented a “beautiful, but incomplete idea” of a fraught civil society. By naming the divisions between Black and white Americans as a main fault line, Ringgold redescribed the symbolism of the flag not as an abstraction but as a problem of the present. Amid the stars and stripes, which vacillate between foreground and background in a trompe l’oeil effect, she positioned three bleeding figures: A knife-wielding Black man and a suited white man flank and lock arms with a peacemaker, a diminutive white woman—a scene that functions as Ringgold’s critical reflection on her own erasure as a Black woman.

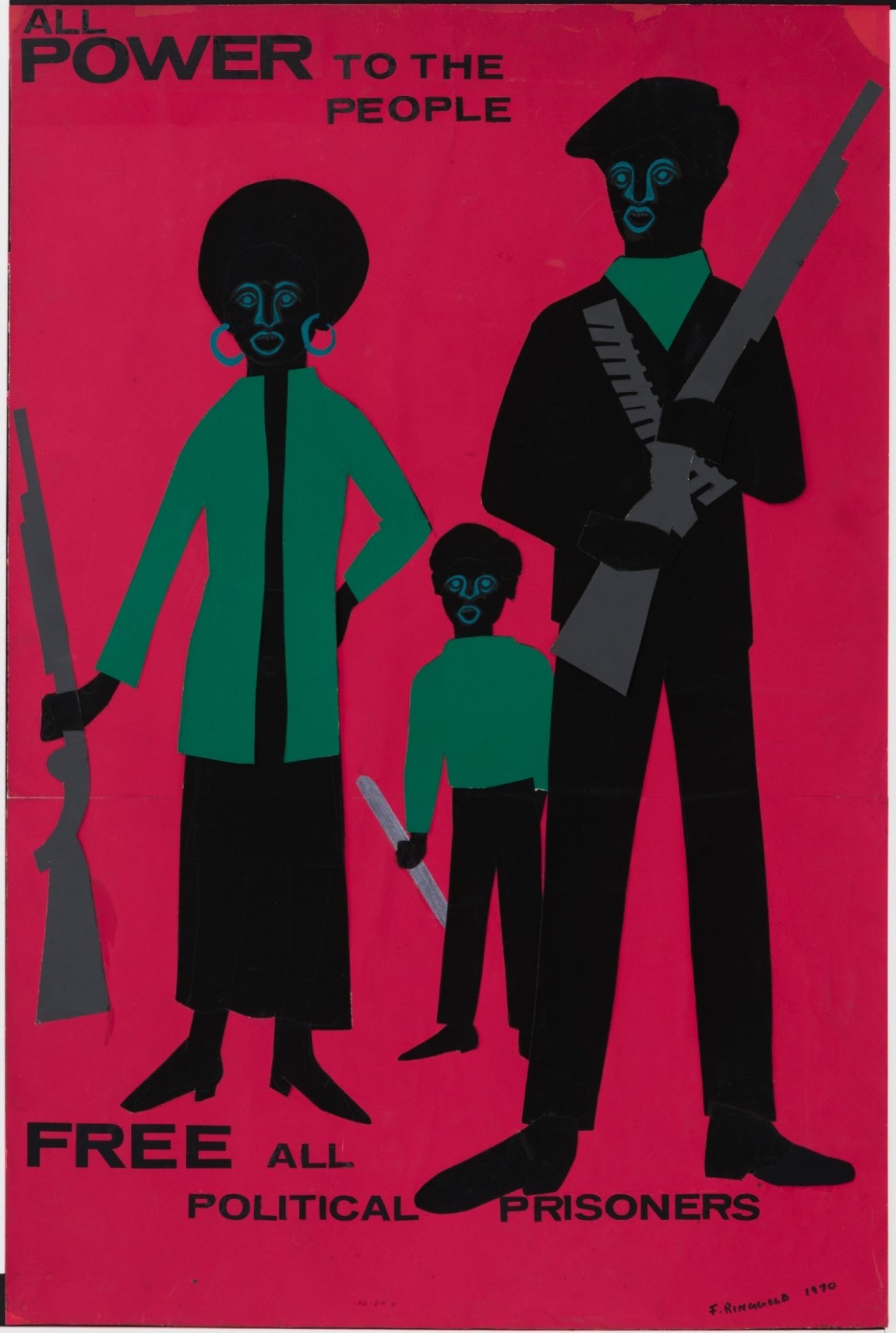

U.S. Postage Stamp uses a similar trompe l’oeil technique, with competing slogans (the hidden WHITE POWER and more immediately visible BLACK POWER) lodged within a panoply of cropped Black and white faces. Such bold graphic lettering reappeared in the many banners, picket signs, and posters that Ringgold created and put to use in the 1970s as a member of the Art Workers’ Coalition, the United Black Artists’ Committee, the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee, and Women, Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation—a history the exhibition registers with a small vitrine of archival documents.

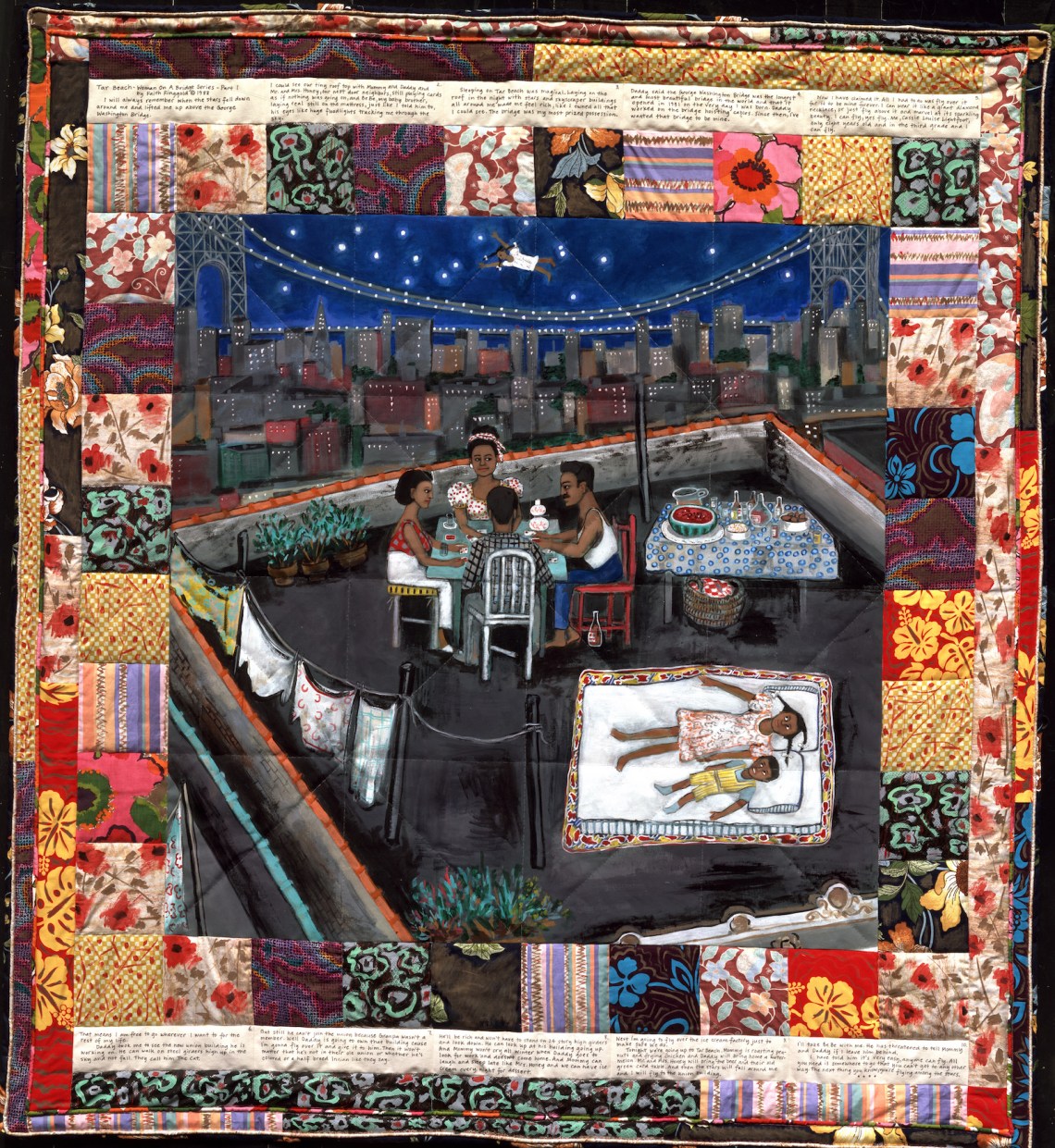

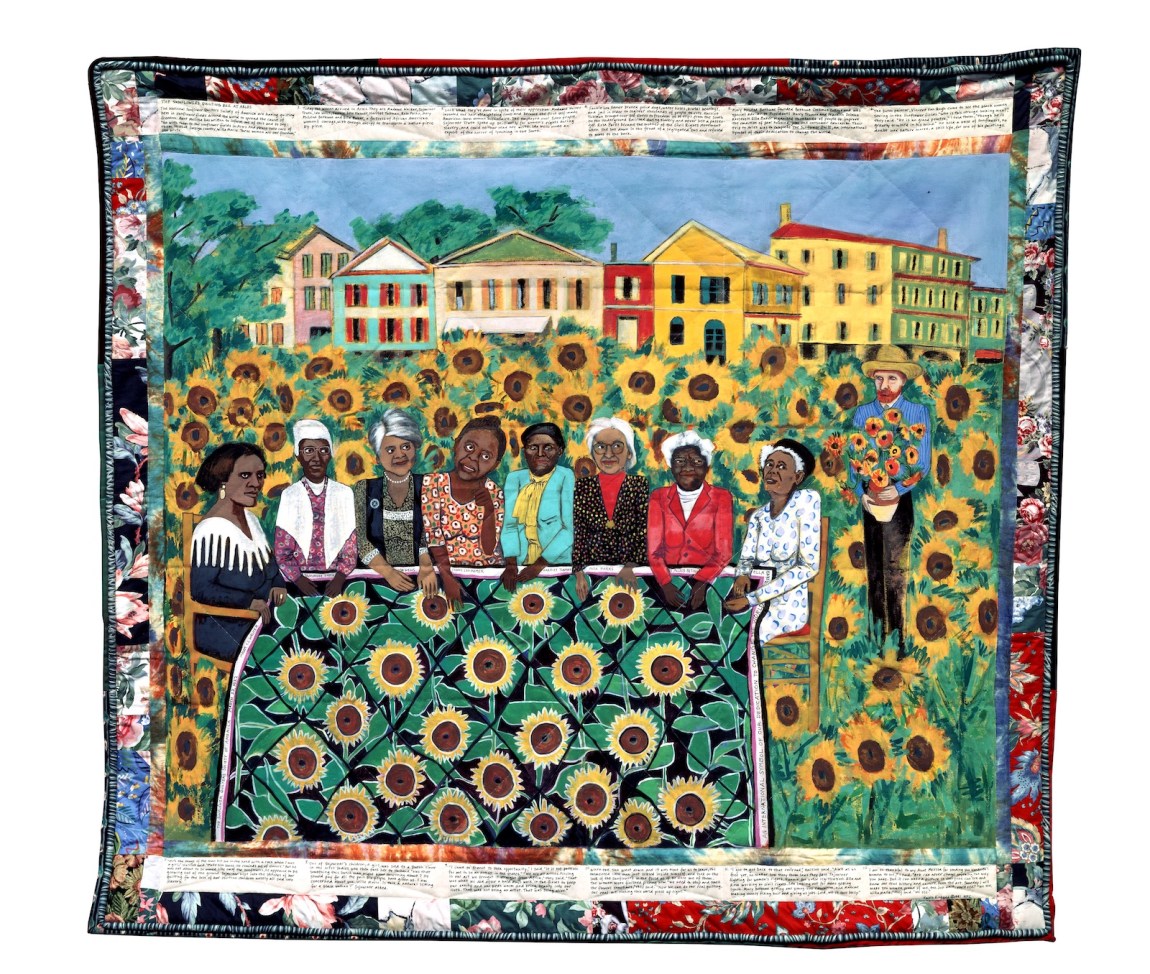

If these early paintings demonstrate Ringgold’s artistic commitment to the social and political concerns of her time, her later work shows her mastery of narrative form. Ringgold began making her “story quilts” in the 1980s, when she found herself the only surviving member of her immediate family and therefore the sole repository of stories she’d heard from her mother, grandmother, and aunts. In presence, scale, and titling many of these quilts resemble classical history paintings. Two major selections of quilts on view come from the respective series The American Collection and The French Collection.

By combining personal experience and imagined encounters, these intricate textile works rewrite American and European art history from a Black woman’s perspective. Her bold interpretations of history drew from sources as diverse as Tibetan tanka, Bakuba textiles, and Dan masks from West Africa. In Two Jemimas (1983) Ringgold depicts two monstrous figures in a direct address to the racist mammy trope that vilified Black women in popular media; for Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s (1991), Ringgold positions an avatar, a younger Black girl named Willia Marie Simone, among the attendees of Stein’s famous Paris salons. In quilts such as The Bitter Nest series and one recounting her own weight-loss journey Ringgold combines text and image as she did in her paintings and posters, writing herself directly into the fabric of American tradition.

*

Ringgold began formally organizing her memoirs in 1977, but it wasn’t until 1995 that We Flew Over the Bridge finally found a publisher; despite her many contributions to visual culture, it was always an uphill battle to assert her place in it. Her ethic, however, has always been one of shared authorship with the generations of Black women who preceded and followed her—including her mother and her daughter Michele Wallace, both of whom collaborated on her fabric works. Her art was supported and informed by her career as an educator. She spent nearly two decades working as an art teacher and two more as a professor of art practice at the University of California at San Diego. Her audience was multigenerational. That many of her story quilts were later adapted into children’s books suggests that Ringgold’s art, informed by the past, was consistently progressive in its address to posterity.

This is the Faith Ringgold I first encountered, and first loved, as a child in a New York City elementary school. Well before I could read or write I was captivated by her 1991 children’s book Tar Beach, based on the 1988 story quilt of the same name. One image, which also appears on the cover of We Flew Over the Bridge, depicts a young girl floating across the darkened city skyline, the span of the George Washington Bridge behind her. Small flecks of white light her path as she soars above her family. I was struck by that depiction of freedom, of being propelled by the sheer force of imagination, which I now know requires looking back as much as looking forward.

Advertisement