According to his mother, as Roland Penrose and John Richardson both recount in their biographies, Picasso could draw before he could speak. “The first sound that he made was ‘piz, piz…’—baby language for lapiz, i.e., pencil,” Richardson writes. “When given a pencil, the infant would apparently draw spirals that represented a snail-shaped fritter called a torruela.”

Richardson adds that “none of the earliest drawings have survived, so these accounts have to be taken on faith.” By the time Picasso was nine, however, his mother began to keep the work he was making. This gives us the first two works on display in “Picasso: Cut Papers” at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles: cutouts in paper of a dog and a dove, both dated circa 1890. While these do not show any particular signs of early genius, they do point to a moment when Picasso’s mother began to see the need to preserve for posterity everything that her son made.

Picasso, from an early age, worked with anything that was to hand. Richardson reports that “Picasso himself remembered that while other children played…he would make drawings in the dust.” And his secretary, Jaume Sabartés, wrote that at seven Picasso would borrow his aunt’s embroidery scissors and with his “skillful hands cut out animals, flowers, strange garlands and groups of figures.”

He did not just draw on paper but used it as a material that he could cut and mold and reshape and tear. The first piece at the Hammer that displays his ability to suggest an entire presence using the minimum of means is Man’s Head Seen from Behind, a drawing of the back of a man’s head on a tiny torn-out scrap of newsprint—Le Matin, December 30, 1906—that includes one ear and the neck behind it and a part of the jawline beneath it, plus the finely cropped hair and the collar of a jacket. In this fragment a person is conjured up, an entire illusion of density and depth is created. It is easy to imagine this young man turning around full-face.

Student with a Pipe, from late 1913 or early 1914, is oil and gouache on canvas, with gesso and sand and charcoal, but the pipe is a paper cutout and the big brown beret on the student’s head is a scrunched-up piece of paper stuck onto the canvas. Part of the effect is humorous, as the work sets out to propose a kind of provisionality for both the human figure itself and the human figure in a painting. If there is one perfect piece made by Picasso using scissors and paper, it is Dove in Flight, from circa 1922. The artist serrated the edges of the paper with both freedom and precision to suggest feathers in flight, making curly and clever cuts to imply shorter feathers toward the neck of the bird.

In 1943 in Paris, Picasso spent a good deal of time in restaurants, where he found the paper tablecloths and napkins useful. The Hammer show includes pieces of paper from that time, items that could so easily have been thrown away. Head, for example, is just over one inch by one inch, a torn scrap with two holes and a tiny mouth that look as though they were burned into the paper by a cigarette. There is a small burn-smudge for a nose. What is uncanny is how close this is to an actual face, a person or an animal looking to its left, slightly alarmed, somewhat curious. These works were photographed by Brassaï, who wrote how Picasso made doglike figures with paper to console Dora Maar, whose dog had died: “At every meal for several days Picasso resuscitated the little dog with his big dark eyes and floppy ears. The nose, eyes and mouth are sometimes poked out, but more often burned with the embers of a match or a cigarette.”

Some of Picasso’s paper works were made to amuse his younger children, Claude and Paloma, in the 1950s. He made a trapeze artist floating free from the rest of the paper, the cutout of her figure making her movement more graphic. He also made a man in a boat with his cutout head and legs in a comic, colorful assemblage. And he made masks, the most striking and evocative formed from a flattened foil-lined cardboard box.

On a few of the very small cutouts there are numbers inscribed, catalogue numbers for Picasso’s great archive. In three pieces from 1961, the number can be seen as disfiguring the small, helpless, delicate cutout, but it is also a sign that anything Picasso did was treasured and looked after for posterity. There is something slightly ludicrous and bloated about some of these more throwaway and casually made objects being exhibited and given a full page in a catalogue.

Advertisement

Picasso’s later work with paper arose from two collaborations, one with a locksmith and ironworker in Vallauris, Joseph-Marius Tiola, the other with the photographer André Villers. Between 1957 and 1965, Tiola and Picasso collaborated on over a hundred sheet metal sculptures. Picasso would begin by making a paper maquette; Tiola would make a version of this for his own use and return the original, which Picasso would add to his archive. Many of these are exhibited at the Hammer. It is interesting that while Picasso held onto everything, Georges Braque, when he created paper sculptures to prepare for a painting, did not preserve them. Allegra Pesenti, who organized the Hammer exhibition with Cynthia Burlingham, writes in a catalogue essay that “no examples by Braque survive and only one, from 1914, is recorded in a lost photograph.”

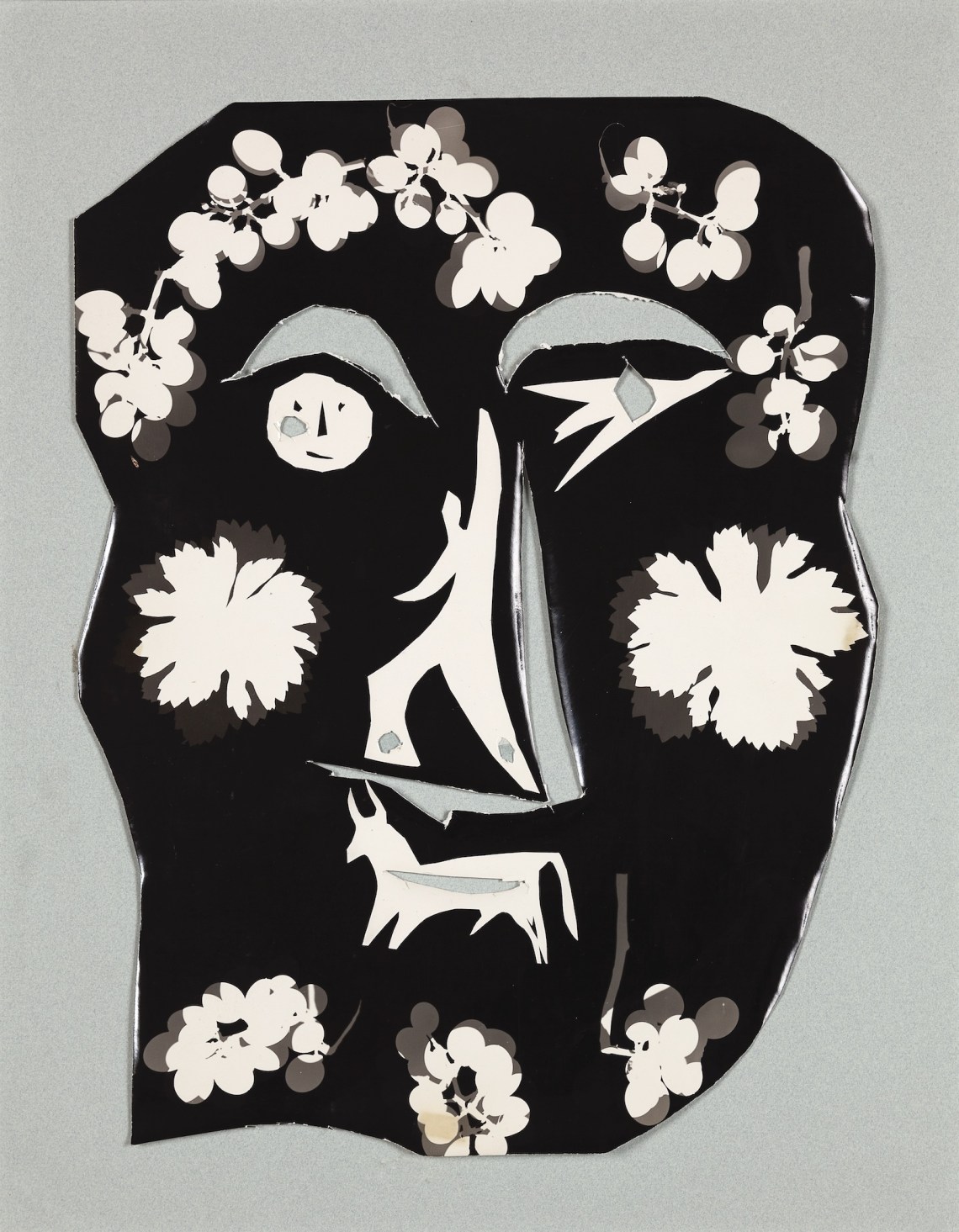

André Villers was in his early twenties when he began to work with Picasso. “We should do something together,” Picasso told him. “I’ll cut out little figures and you’ll take photos. You’ll enhance the shadows using the sun. You’ll have to take thousands of shots.” They collaborated between 1954 and 1962 using photograms and multiple exposures to superimpose images by Villers onto Picasso’s cutouts.

This sequence of images—called Diurnes—is the most substantial work on display at the Hammer. The painter and the photographer were clearly enjoying themselves with an iconography that includes mythological figures, familiar faces (including Jacqueline Roque, Picasso’s wife), music-making, flora, and foliage. In one, we see a cutout of Jacqueline’s head. In the next, that silhouette has been overlaid by the photographer with a picture of a fruit tree. It is the same shape, but leaves and branches now form its texture. In other images, there are faces and profiles made by Picasso, using paper and scissors, and then worked on by Villers so that a rich imagery—lacework, boats in a harbor, bare trees, rock, a leaf, a house—is layered on Picasso’s cutout.

Since Picasso was in his late seventies when most of this work with Villers was done, it is a sign, if we needed one, of how much visual energy he could still radiate, how much playfulness and innovation. Diurnes might seem marginal, merely amusing, until we see it image by image at the Hammer. On its own terms it is fully satisfying, complete.