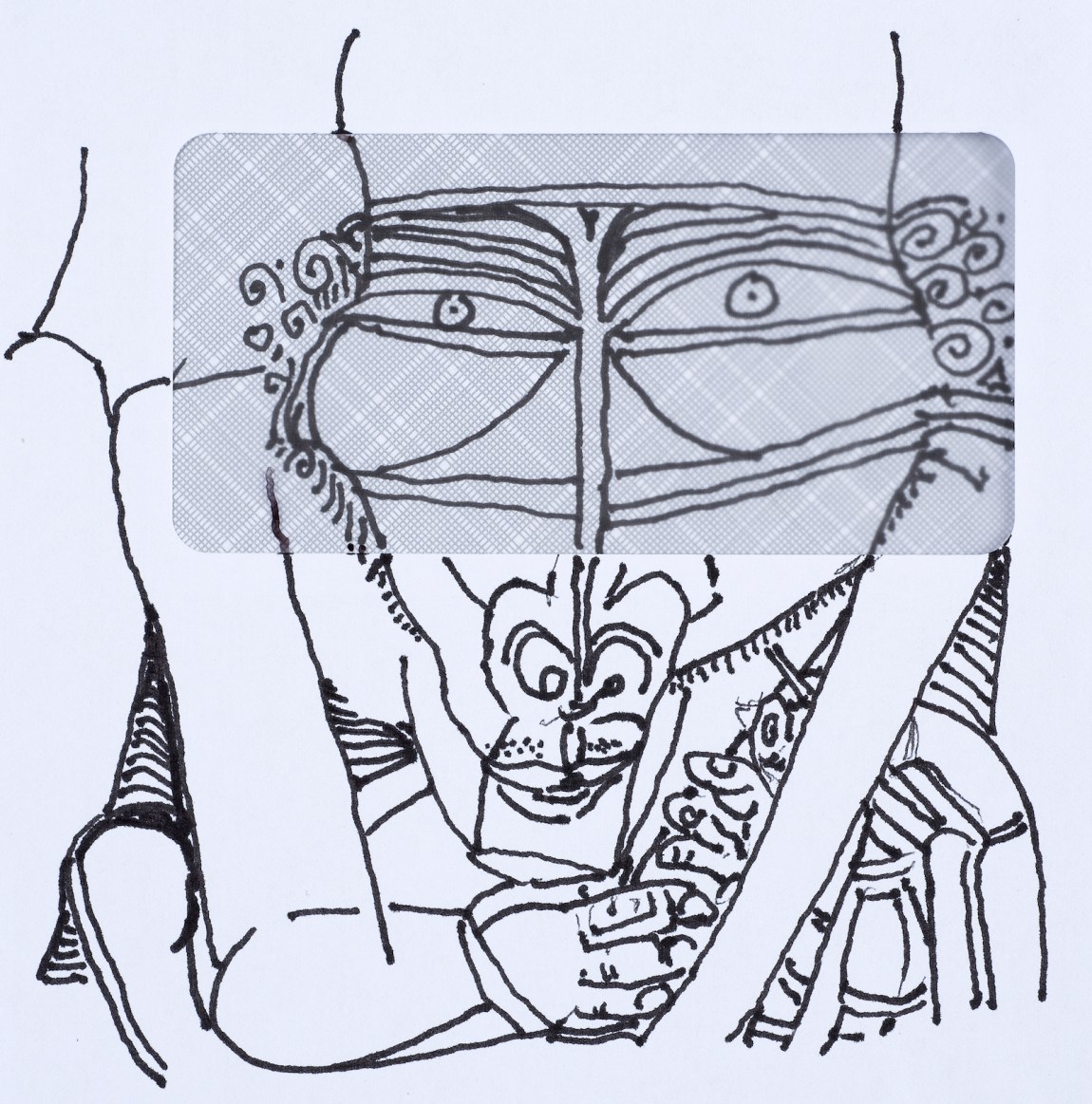

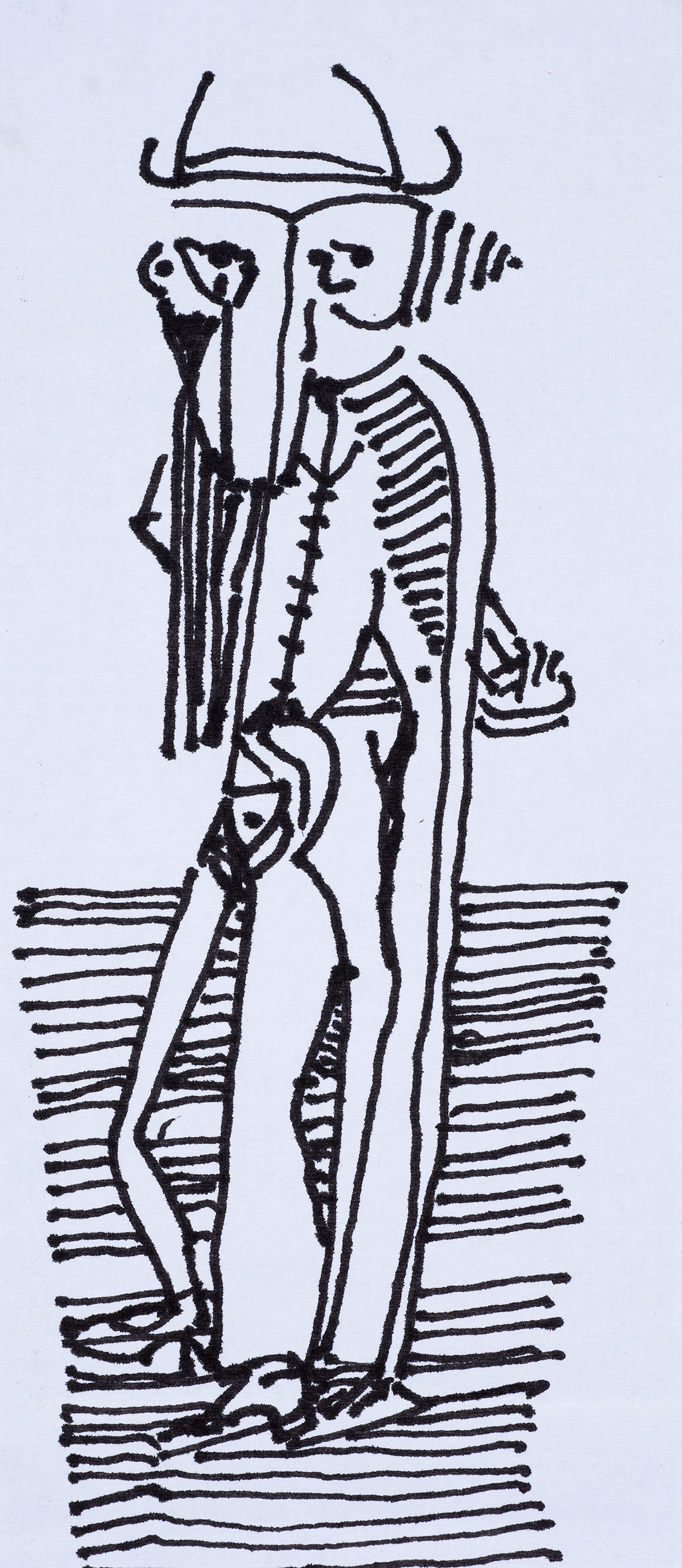

The face is a mask, vaguely leonine, narrowing from its enormous eyes to a snout of flared nostrils and a small mouth, twisted into what might be a grimace or a grin. The contours of the nose branch up into a network of wrinkles around the eyes, then extend out into fiddlehead ferns sprouting from the temples. The gaze is so insistent that it is easy to ignore the virtuosity of all the little lines: the sagging pouches of the eyes, the subdued yet prickly whiskers along the jaws, the dots of stubble on the upper lip and double creases at the knuckles, the striped upholstery of the chair. Strikingly, the sitter’s left arm seems to reach out beyond the frame, which crops the arm at its wrist. Is he holding up a mirror to himself (or a phone)? It is a self-portrait of the artist in an armchair, examining himself—and us—through a screen.

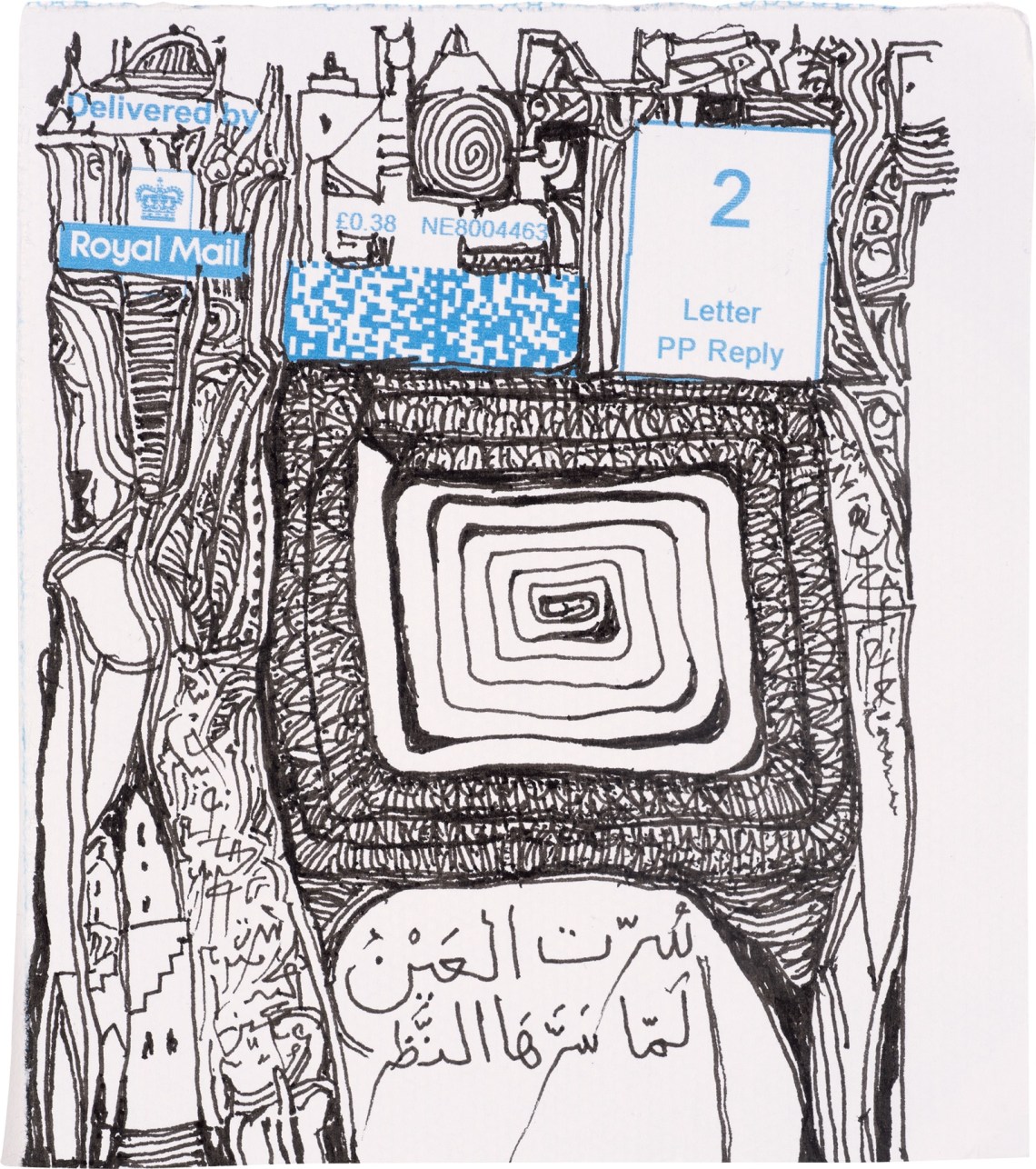

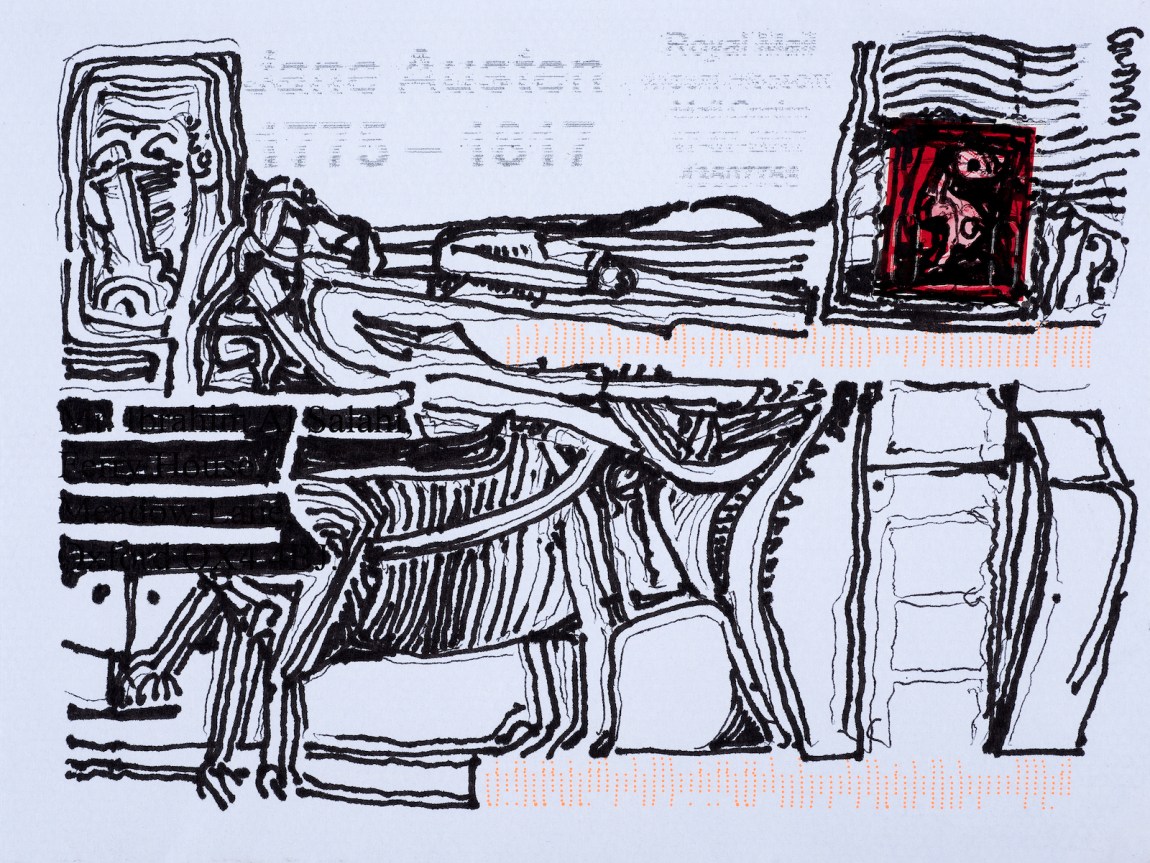

The screen in this case is the plastic window of an ordinary envelope, which constitutes the support of the drawing. Each work in the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi’s beguiling series Pain Relief Drawings, now on display at The Drawing Center, is drawn on a found canvas of this kind. As Laura Hoptman, the show’s organizer, explains in the catalog, El-Salahi started the series in 2016 at his home in Oxford, England. Suffering from back pain and Parkinson’s disease, he decided to convert his empty boxes of painkillers into materials for art. Many of the drawings, done in waterproof ink, show the creases where El-Salahi, now ninety-two, flattened out the small cardboard containers, as though readying them for recycling. In some works, he uses those creases—just as he uses envelope windows or stamps—as elements of the composition.

Once you’ve recognized the artist’s self-portrait, you begin to see it everywhere in El-Salahi’s work. The face is variously disguised, reduced to its basic lineaments, or severely cropped. Walking slowly through the small but absorbing exhibit of 122 drawings, you sense the artist playing peekaboo with his audience. Although El-Salahi’s visual code is often abstract, this self-conscious playfulness, along with the everyday materials he works with, adds a surprisingly intimate note to the show (one of the envelopes includes his home address). Each square is a kind of miniature essay, an effort to observe the self from a properly artistic distance—through a screen, as it were—as well as from up close.

A younger version of the same face—its whiskers more luxuriant, the cheekbones less pronounced—crops up in earlier works by El-Salahi, most notably Prison Notebook, a series of ink drawings with accompanying texts composed in 1976 following a six-month sentence in Kober Prison, north of Khartoum. (A cousin had mounted a coup against General Nimeiry, and El-Salahi’s incarceration seems to have been a matter of guilt by association: he was never put on trial.) During the previous twenty-five years, El-Salahi had become among the most successful artists in Sudan. After studying at Gordon College, a training ground for the colonial elite, he attended London’s Slade School of Fine Art from 1954 to 1957. He returned to Sudan, which gained its independence in 1956, and became a prominent member of what was known as the Khartoum School, a loosely affiliated group of artists who worked to create an aesthetic for the new nation by borrowing from Arab as well as African styles. El-Salahi produced oil paintings, illustrated Tayeb Salih’s novel The Wedding of Zein, and took a number of powerful posts in the Ministry of Culture—apparently, as the artist Hassan Musa argues in his catalogue essay, out of patriotic obligation rather than ideological zeal.

El-Salahi’s work was not—and has never become—explicitly engagé. (In the 1960s, he contributed to the Beirut-based Hiwar [Dialogue]—funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, later revealed to be a CIA front group—which advocated a supposedly apolitical modernism.) Prison Notebook is less a document of political defiance than a nightmarish record of confinement. In one of the notebook’s pages we find the artist, his face a mask of worry, squeezed between the walls of a tunnel barely wide enough for his slack, emaciated body. The bird perched on his shoulder appears in other drawings from the series as a bearer of spiritual wisdom. The accompanying text reads, in part, “I’m lost with no guiding light, no doors, no exit.”

While in prison El-Salahi invented a new method for his drawings. As he recalls in a commentary he gave for the images in Prison Notebook:

Advertisement

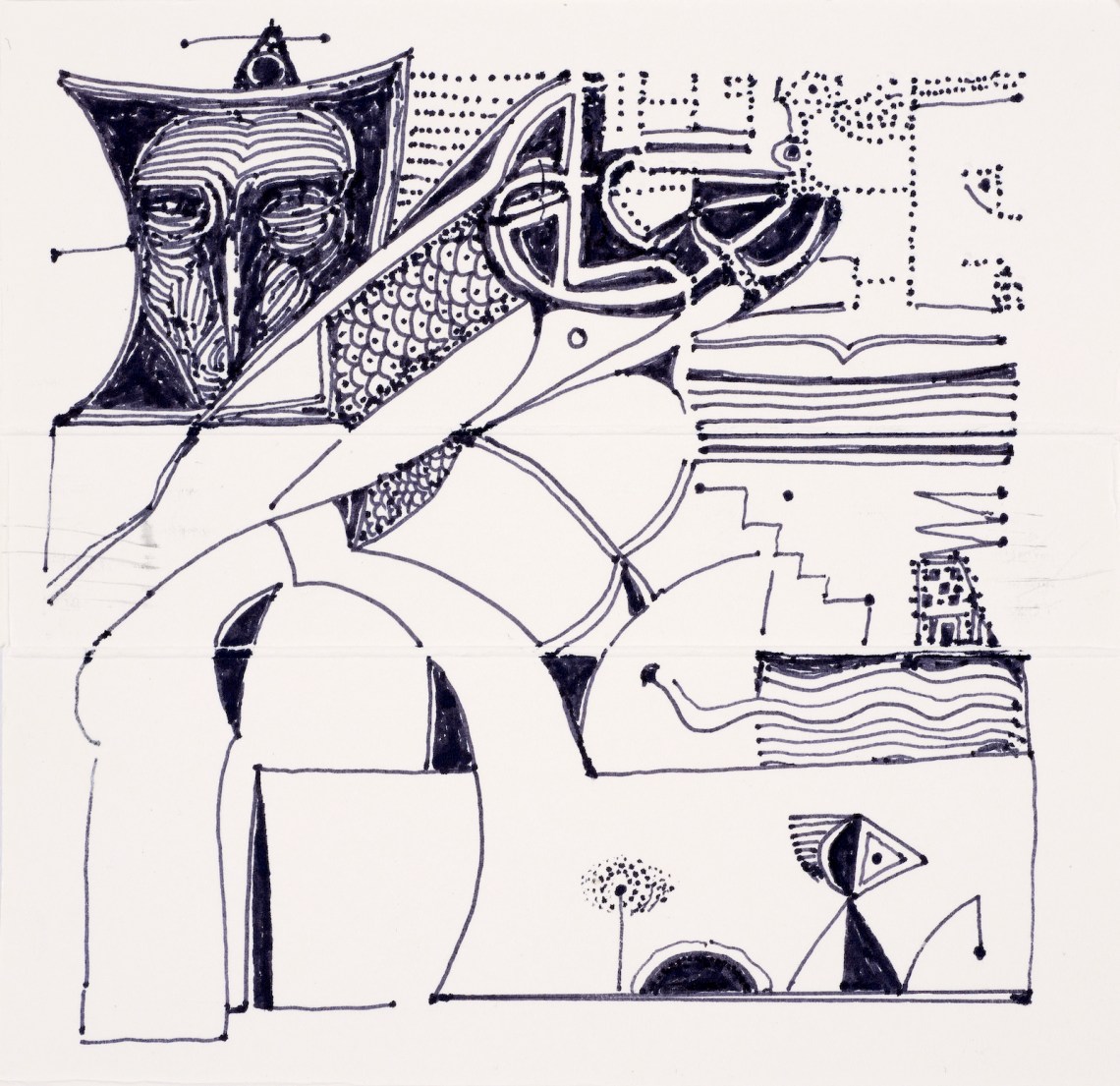

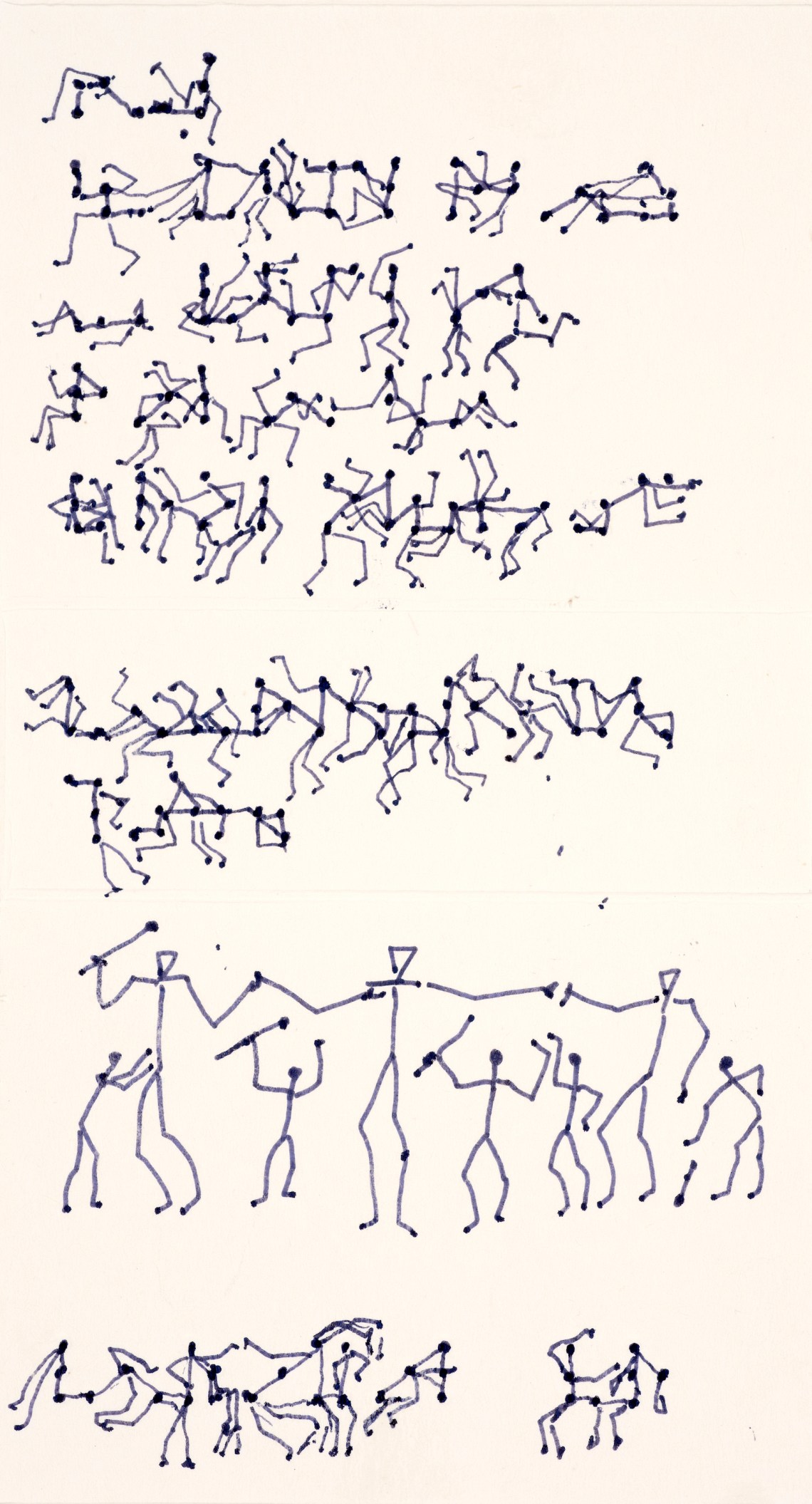

I had some cement bag casings, and I chopped them into small pieces…I used to make very tiny drawings on these little pieces of paper that I buried in the sand after finishing them. I worked on a nucleus, so something in the middle. Then I added one piece to the side on the right, then one piece to the left, one piece above, one piece below, until the picture grew into another image.

This method of construction—elsewhere El-Salahi calls it “endless organic growth”—is evident in Pain Relief Drawings, also executed on small pieces of paper or cardboard, with motifs that seem to exfoliate outward. He has referred to each work in the new series as itself a nucleus, or an origin. His anecdote about making art while in prison also suggests the importance of physical constraint in his practice. In many of El-Salahi’s drawings, the lines seem energized by the cramped spaces they fill; their torque is enhanced by their confinement. A different but related tension animates Pain Relief Drawings: these works are at once expressions of suffering—of being confined to a chair, or a bed, or a body in pain—and the traces of artistic pleasure and liberation. “When I work,” he has said, “I don’t feel pain at all.”

Another distinctive element of El-Salahi’s art is the presence of texts: Quranic quotations, snatches of popular song, fragments of original poetic prose. Many of the medicine boxes he uses are marked with braille. In his works from the 1950s and 1960s, often done in oil paint, calligraphy is an essential element. But the letters are typically broken off, turned upside down or inside out. El-Salahi has compared his treatment of Arabic letters to Picasso’s cubist treatment of the object:

At first I wrote a kind of gibberish…using the letters without meaning. Then I started to break the letters. I was interested in the rhythm within the writing. When you write, you put down the letters in a line, and then another line. But when you have a closer look, when you magnify it, you find the shape of the letters and also the shape of the spaces between them, and that gives you another rhythm…[I]t’s like hieroglyphs.

The scale of El-Salahi’s most recent work is small, but its ambition can be breathtaking. He limits himself to the most basic materials—lines, spaces, rhythms—to make hieroglyphs for our world.