It was Christmas week, New York City was facing off against a dangerous winter storm, and the mayor was nowhere to be found. The fact that this sentence could have been written in 2010 for Mayor Michael Bloomberg as it is being written about Mayor Eric Adams at the start of 2023 points to a pattern of attitude and policy in New York City government that has proved immensely durable since the city’s fiscal crisis in the late 1970s.

Stylistically there are of course differences between the billionaire Bloomberg, who belonged to the oligarchy that has ruled the city for the past fifty years, and the once blue-collar Adams, a former cop enamored of and indebted to that ruling class. Adams often finds himself palling around with its lower level, a rogues’ gallery of grifters, as opposed to the high rollers with whom Bloomberg surrounded himself. Bloomberg jetted from gala to gala, occasionally descending to walk among the people (which is to say, Goldman Sachs employees in need of a pick-me-up). Adams, meanwhile, has popped up at a cryptocurrency conference, a Wells Fargo event promoting predatory credit for renters, and a birthday party for tax-averse restaurateurs.

But neither could be found when conditions were at their worst. Bloomberg famously skipped out on a Christmas blizzard to soak up the sun in Bermuda, and Adams—well, his staff was tight-lipped at first, refusing to say where the mayor was as a storm pummeled the northeast. This evasion led to some of the funnier press conferences in recent memory, during which put-upon Deputy Mayor Lorraine Grillo had to explain that the mayor was “resting” at an undisclosed location. Eventually Adams revealed that he was in the Virgin Islands.

Going on vacation is not in itself a scorn-worthy offense. But the fact that it took Adams’s office so long to give his constituents a straightforward explanation of his whereabouts raises a question that has hovered over much of his time in office: What are New Yorkers, regular New Yorkers, owed by this City Hall? Like Bloomberg before him, Adams seemed to be signaling that when the city’s residents battle headwinds, whether of a storm or of an ever-deepening affordability crisis, they’re pretty much on their own—unless, as always in the gilded city, they can afford to buy their way out.

The concrete effects of that affordability crisis can be felt and seen throughout the city. Local eviction moratoria have expired just as federal Covid relief diminishes and rents skyrocket at a pace with which working and even middle-class New Yorkers can’t keep up. City shelters see more families, and single men especially find themselves either without a stable place to stay or on the streets. Without support, mental health issues go untreated and drug use increases. 2,668 people died of drug overdoses in New York City in 2021, an increase of 78 percent since 2019 and 27 percent since 2020. Overwhelmingly, these New Yorkers were Black, Latino, and low-income. The city’s oppressed are not only struggling, they’re dying from despair on its streets in unprecedented numbers.

People experiencing deep hardship and pain are more visible in the city than they have been in some time, especially in the subway. When the city took proactive steps to find housing for people at the height of the pandemic, it dramatically cut down on the number of people sleeping outdoors. But once those steps were no longer taken, the amount of people on the streets rebounded to over 3,400, a number many advocates for the homeless believe was a drastic undercount.

The city’s job is to assist those people. But more than a year into his mayoralty, Adams has instead relied—more than even many cynics had anticipated—on “quality-of-life” policing against low-level criminal actions like fare-beating or misdemeanor theft to force the people who need help out of sight and out of mind. His signature policy is his November announcement that the city would start instructing its police officers to involuntarily hospitalize people experiencing mental health crises if they appear unable to take care of themselves. Officers already had the authority to bring someone to a hospital (where they might spend days before going to a specialized psychiatric unit) if they seemed to pose “serious harm” to themselves or others, but are only now being trained on the more subjective determination that they cannot manage their own needs. The announcement, which surprised even the police commissioner, represented the culmination of a year spent demonizing those on the lowest rung of the city’s ladder.

*

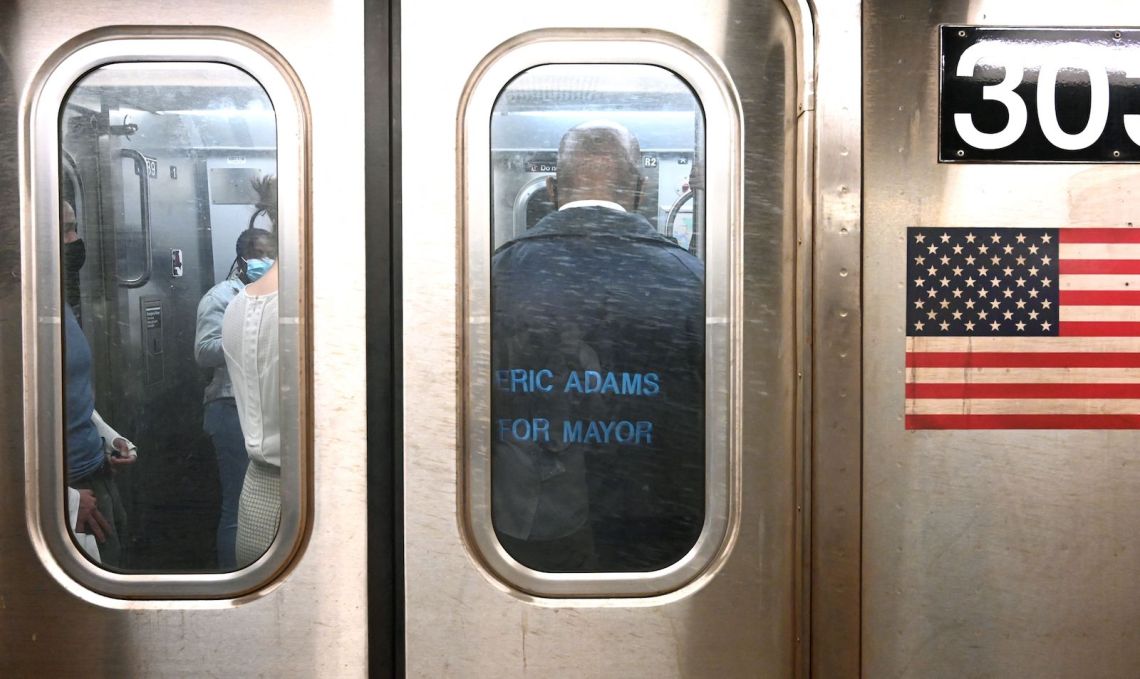

Eric Adams barely won the 2021 mayoral Democratic primary, a chaotic race in which the only constant was that he was always going to get around 20 percent of the vote. Relying on Black voters in southeast Queens, the adjacent neighborhoods in Brooklyn, and the Bronx, as well as on support from the city’s largest public sector labor union, DC 37, Adams could have been outflanked by a more liberal candidate on issues like policing, housing affordability, and public school funding. But that liberal effort self-sabotaged: Scott Stringer, the heir apparent, was undone by a sexual misconduct allegation, and progressives failed to settle on a backup. Their votes were split between the late-surging civil rights lawyer Maya Wiley and the technocrat sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia. New York City therefore found itself with a fairly conservative law-and-order mayor who’d had almost no signature achievements before entering Gracie Mansion.

Advertisement

Over the following year, as Kim Phillips-Fein recently argued in these pages, Adams used a debatable “fiscal crisis” to promote austerity and gut the city’s administrative state, limiting its ability to react to threats both real and imagined. Thousands of New Yorkers now face food insecurity each day because the city has been unable to properly staff offices that process food benefits. People have lingered in homeless shelters while designated housing units sit empty, again for lack of staffing.

This past summer migrants from the southern border were bused to New York by Republican governors seeking to somehow show up the Biden administration’s handling of immigration. Adams used the situation to try to curtail the rights of homeless New Yorkers by reassessing the city’s “right to shelter” agreement, which guarantees access to a shelter bed every night. The city’s shelter system, a hodgepodge of permanent shelters and hastily converted sites, can flex itself into a much larger network when necessary by renting hotel rooms, at great cost. Still, because it has never had the infrastructure to deal with chronically high homelessness levels, to say nothing of large spikes, it is easily overwhelmed.

Adams was quickly rebuffed by other politicians for his plans to tinker with the city’s policies and backed off. And yet he has kept trying to shift blame from his own lopsided budget. In December, speaking about the need for federal assistance, he warned that “every service we provide is going to be impacted by the influx of migrants in our city.” (To his administration’s credit, beyond the mayor’s rhetoric, much has been done to accommodate migrants in New York, and the just-passed federal budget will in fact reimburse the city for some of those costs.) Earlier this month, Adams unveiled a proposed budget that would keep police funding the same but cut drastically from libraries and the city’s nascent universal childcare programs, as well as many other social services.

Adams often speaks about the importance of such services for proactively preventing violence. But his budget shows no such concern, and he himself has consistently helped stoke fears about a spike in crime in the city. Shortly after its successful effort to get Adams elected, the New York Post, the city’s only remaining fully staffed tabloid, ramped up its tradition of plastering its front page with stories of violence and predation. The media market followed suit, and for much of last year local news was dominated by stories about how dangerous New York City streets had become. The murder rate actually fell between 2021 and 2022, but airwaves and newsstands were full of stories about violent acts and eye-popping statistics about the increase in property crimes.

Adams, meanwhile, set his sights on rolling back criminal justice reforms meant to keep nonviolent offenders out of the abattoir of Rikers Island, claiming that police could no longer do their jobs because New York’s criminal class was simply being released to commit more crimes. (In fact, study after study has found that bail reform had no impact on the crime rate.) Even as he tried to get its economic engine fired back up, Adams was somewhat confusingly still calling the city “dangerous” and insisting that he had “never witnessed crime at this level”—possibly to prove that only he could fix it. The collapse of New York’s Democratic candidates in November’s midterms correlates neatly with its suburban areas, where many voters experience the city through the prism of TV news, the Post, and Adams’s fearmongering. Shortly after those elections, Adams upped the ante still further by announcing his involuntary hospitalization plan.

*

“I want to get you to care about someone like me,” announced Ibrahim X, a New Yorker who was involuntarily hospitalized by the NYPD well before the new policy took effect. He was speaking at a rally opposing Adams’s plan on the steps of City Hall in early December. “Before you can help me, you’ve got to care about me.”

Adams had cloaked the announcement in compassion: it was cruel, he suggested, to let people be a danger to themselves rather than getting them help, whether they wanted it or not. But caring for the people who would now be brought into understaffed hospitals was another matter, one that Adams had already deprioritized by ordering the gutting of the city’s social services. Also speaking at the rally were doctors and healthcare providers who reported that, within hours of being detained, many people would be back out on the streets, either without a treatment plan or on a weekslong waitlist for care.

Advertisement

“It’s just a Band-Aid over a major problem,” Dr. Pierre Arty, the chief psychiatric officer at the nonprofit Housing Works, told me. “This is not a plan, this is just a masquerade.” Mental health professionals believe the answer to that problem lies instead in redirecting resources to supportive housing, outpatient treatment centers, robust drug treatment, safe injection sites, and other tried-and-true programs. Governor Kathy Hochul has already picked up on their suggestions, proposing over a billion in spending on many of these types of services.

“At any moment, so many New Yorkers can look erratic,” said the twenty-nine-year-old organizer Je’jae Mizrahi, who had come out to protest the new policy. Police officers “can say, ‘oh this person looks problematic, let’s whisk them away and put them in a state facility, and who knows how long they’ll be there.’” Mizrahi, who struggles with mental illness, said that even with a care team in place, they were still involuntarily hospitalized last year when the NYPD responded to an anonymous call about an “emotionally disturbed person.” They spent several days receiving care they considered unhelpful and unnecessary.

Within days of the announcement, groups that work with people experiencing mental illness appeared in federal court to fire the first salvo against the policy. Building on an ongoing civil rights case, the groups charged that Adams was making an existing, disastrous policy much worse. They argued that he was dramatically expanding the role of law enforcement without giving the NYPD adequate training, and they noted several high-profile cases in which the NYPD, responding to a report of an unarmed “emotionally disturbed person,” had ended up killing that person. Further unnecessary police interaction with people in mental distress, they insisted, would only lead to more of these tragedies. One of the arrests that spurred the original lawsuit against the city happened after a mother pleaded for police not to arrest her son; he needed treatment, not to be confronted by police officers. (The officers went on to arrest the mother as well.) On top of these concerns, lawyers challenging the policy worry that people taken to an emergency room against their will would have no one to advocate for them as they navigate the labyrinthine health care system—those in the criminal justice system at least get access to an attorney within twenty-four hours.

At the hearing, a lawyer for the city explained that Adams wasn’t actually changing the NYPD’s purview, just alerting police officers to what state law already allowed. The eighty-one-year-old District Judge Paul A. Crotty deferred ruling on the matter, allowing the policy to move forward while the plaintiffs and the city worked on further briefings.

*

Adams has made his priorities clear. The question is how the progressive coalition within the city council, which was forged during Bloomberg’s third term and grew during the bumbling de Blasio administration, will respond to them. The coalition’s left, represented by the council’s socialist members, has taken the lead in criticizing Adams’s involuntary hospitalization plan and his other priorities. They were never going to play ball with him.

The center flank, represented by the Park Slope and North Brooklyn liberals who learned their trade under Comptroller Brad Lander, has also opposed the hospitalization plan but found itself on Adams’s side of other debates—including voting for a budget that drastically cut school funding last year. And the right flank, which now controls the bloc and often reins it in, would very much like to keep the relationship with Adams cordial, since the mayor wields considerable power over money the council’s leadership needs to deliver to nonprofits. (Adams recently asked the council to slash that discretionary funding in half.) Their response to the hospitalization plan has been muted. Municipal unions, which can sometimes help give the progressive coalition the weight it needs to get things done, were relatively staid during the first year of the Adams administration. They are in the midst of negotiating new contracts with the city and need Adams as a partner, not an adversary.

The mayor isn’t invulnerable, and this year’s fight over the city budget is already shaping up to be the most contentious in a decade. Adams has had little success pushing his legislative priorities at the state level, and his relationship with the city council is already severely strained. (He and Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, who hugged him during last year’s budget agreement, were as of October reportedly no longer regularly speaking.) Without the financial resources Bloomberg was able to muster to get reelected twice as a relatively unpopular incumbent, Adams could face a serious primary challenge—if anyone is willing to risk their political careers on it.

But Adams has also found some unexpectedly large pockets of support. Chinese immigrants in South Brooklyn and lower Manhattan and reactionary post-Soviet communities in places like Brighton Beach have embraced his views on crime and bail reform, as have Orthodox Jewish communities. All three groups would like to see a tougher hand from the NYPD, especially as hate crimes against Asian and Jewish New Yorkers have increased. These same communities helped buoy the campaign of Trump-aligned Lee Zeldin in the shockingly close gubernatorial election; in much of South Brooklyn, it was a blowout for Zeldin.

Adams himself has changed party affiliation when it suited him, and although doing so would be political suicide in New York City, he could remain a Democrat in name but rule as the conservative he is, forging a coalition that unites these immigrant enclaves across the city with Black union-member households in the outer boroughs. For the obscenely wealthy New Yorkers who benefit from his policies, this would be an ideal coalition behind which to hide their own aims.

There’s currently no flag-bearer for the opposition to Adams, and prominent left politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (constantly summoned if only for the lack of other charismatic high-profile opposition leaders) have mostly stayed on the sidelines of local political issues. Progressive energy in the city is dimming, with an entrenched new administration hostile to the left’s recent victories and aims. If there’s going to be a challenge to Adams, it will most likely come from CUNY and SUNY students facing steep tuition hikes and young people being priced out of the neighborhoods they grew up in. But there has been no signal or sign that politics is the avenue for them to get what they want: for these young New Yorkers, the violent repression of the protests of 2020 and Adams’s election were a one-two punch of demobilization. It’s unclear if enough people with access to power still care about them—at a time when they’ve been dealt blow after blow and still somehow keep going.