Leo McCarey’s 1952 film, My Son John, perhaps the most well-known of the several extravagantly anti-Communist melodramas engineered by Hollywood studios at the height of McCarthyism, opens with two brothers tossing a football outside their house before Sunday Mass. It’s the eve of their departure for the front in the Korean War, but a third brother, John, is notably absent. He’s fled his hometown for a job in Washington, D.C., with the federal government. But when John, played by the skulky cool, queer-coded Robert Walker, returns for a surprise visit, he’s an object of curiosity and suspicion, embodying the kind of lefty limp-wristed intellectualism his family has been taught, in church and by the press, to exorcise. John’s boorish father, a hard-drinking Legionnaire, has all but disowned him. “It’s a commie specialty, breaking up homes,” he growls, as if recounting a newsreel (he probably is). But John’s more forgiving mother, Lucille, tends to him hand and foot, desperate to keep him in the fold. Forcing his palm onto a bible, Lucille asks him to swear he isn’t a member of the Communist Party. “The silver cord,” he had earlier told her coldly, “must be severed.” As is always the case in these films, John is revealed to be a Soviet spy. And when his mother, at its climax, pleads for his loyalty, she brandishes a framed photo of her other sons crouched on one knee in shoulder pads and helmets—“a great pair of halfbacks,” says the FBI agent. Lucille points out that John never played football. “I think sometimes it hurt you,” she tells him.

American football as a shorthand for endangered national values—patriotism, virtue, loyalty—did not begin with the cold war. Fifty-two years earlier, in an essay titled “The American Boy,” written for a children’s magazine, New York governor Teddy Roosevelt counseled young Americans to treat life like a football game and “hit the line hard.” Roosevelt didn’t play football himself; at the time, very few Americans did, and for the first several decades of the sport’s history it existed as a haphazard derivative of rugby played almost exclusively by college students in the Ivy League, where Roosevelt had first been exposed to the game as a Harvard undergraduate. But even leaders of those institutions maligned the sport as unseemly and gruesome. “As a spectacle,” wrote Harvard University President Charles William Eliot in 1905, “football is more brutalizing than prizefighting, cockfighting, or bullfighting.” That year, during which nineteen college football players died in one season from injuries sustained in the course of play, Roosevelt, convinced nevertheless of the sport’s character-building potential, leveraged his power as president to help rehabilitate it.

In October, after several universities canceled their football seasons, Roosevelt invited the coaches and athletics advisers of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to the White House to broker a compromise between the game’s purists, such as the Yale coach Walter Camp, and those who felt it needed to overcome its increasingly dishonorable reputation. From their summit grew the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, later the National College Athletics Association (NCAA), which tried to curtail the game’s more barbaric elements by introducing a number of rule changes, such as the legalization of the forward pass, which helped to spread out the violent scrum at the line of scrimmage, and the introduction of a “neutral zone” between the offensive and defensive lines. Gradually the game began to resemble its current form, but fatalities still multiplied, with forty in 1931 alone. “If football is the testing ground where the real man is revealed…are we to abandon it because death intrudes even there?” asked the dean of Yale College at the funeral of an Army cadet who sustained a fatal neck injury playing in that year’s Yale–West Point game. “I do not think so.”

Over the next three decades, politicians, military officers, and football coaches alike helped portray the sport as a seedbed of military prowess, frequently and brazenly instrumentalizing the game’s savagery as a corrective to what they perceived as the feminization of American men and the dilution of the national character. It was after World War II that these nationalist overtones crystallized both in performance, like the pompous flyover jet rituals that often precede NFL games, and in the self-important rhetoric of the game’s most zealous promoters.

As televisions replaced radios in American households, football overtook baseball not only as the country’s most popular sport but also as an entertainment product. Its ennobling, martial character was significantly enhanced by the small screen. Television, as Don DeLillo wrote in End Zone (1972), made “poetic sport of the wounded.” In the novel it functions as a proxy for the members of a Texas college football team grappling in ways both amusing and tragic with the psychic toll of the Vietnam War. The book’s tortured narrator, a running back named Gary Harkness, channels his bleak fascination with “modes of disaster technology” into football, which somewhat satisfies his appetite for ordered calamity. DeLillo recognized that there was a spiritual alliance between the US military and American football, whose vernacular of glory and self-abnegation could be easily retrofitted to the cause of American exceptionalism. Football, after all, was played nowhere else.

Advertisement

The year after the United States entered World War II and much of the country’s athletic talent went overseas, some two hundred universities halted their college football programs. In their stead, military service teams, often consisting of players fielded from Navy pre-flight training programs, competed against the remaining heavyweights of NCAA football, like Notre Dame and Ohio State. As the historian Kurt Kemper explains in College Football and American Culture in the Cold War Era, coaches and those leading the war effort held steady in their belief that the sport, for its exercises in teamwork and discipline as much as its tactical innovations, should not be made a casualty of wartime imperatives.1 “There is nothing which we can do in the educational field with our youth which will do more toward winning this war than the production of leadership qualities,” one American general told the University of Toronto’s student newspaper in 1942. “As a mechanism for this education there is nothing which can touch competitive athletics and, among this group of sports, nothing which can touch football.”

The passage of the GI Bill in 1944 allowed millions of servicemen to pursue higher education once they returned home. Thousands enrolled in American universities and played for their schools’ football teams. In 1946 the number of college football teams increased almost threefold, from 220 to 650. The greatest beneficiaries of an unprecedented surge in federal subsidies for higher education—compelled, in part, by fears of Soviet technological gains—were large public universities, the new behemoths of American college football. “By the end of the war,” writes Kemper, “military elites imbued the game with a high-minded ideological justification, a justification that many felt was validated with victory over the Axis powers in 1945.”

The long-term economic downturn that many expected might follow a decline in the production of war goods did not come to pass. Instead, the US economy swelled along with its population, and the material lives of most white Americans became easier than ever before. But victory did not forestall anxieties that a postwar culture of abundance had made Americans an idle and decadent people. Memories of World War II were long, and the specter of an even deadlier affair, fought this time with nuclear weapons, loomed large.

*

Cast against the threat of communism, football became the site of a struggle over the American family and, more pointedly, American boys, whom politicians often crudely identified as the last bastion of defense against Soviet risks to the “American way of life,” a euphemism for the free enterprise system and the nuclear family unit. The cold war, moreover, was by its nature patriotically unsatisfying, involving no concrete displays of military prowess or superiority, only the fear that the United States had been both outpaced and infiltrated. For legislators, then, and for the youth football coaches with whom they explicitly aligned themselves, football was a theater for muscular nationalism, throwing the perceived softness of containment policy into relief.

As Kathleen Bachynski documents in her book No Game for Boys to Play, a comprehensive study of the postwar rise of youth football, educators and medical professionals strongly objected to the promotion of football for young boys.2 In 1953 the National Education Association voted 43–1 to declare children too physically immature for contact sports (the lone dissenter was Joseph Tomlin, the founder of Pop Warner Football), and in 1957 the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended against tackle football for kids. In response, sports medicine doctors touted the importance of parental oversight and the supposedly prophylactic benefits of plastic helmets, which went into mass production after the war.

Notwithstanding concerns about the game’s brutality, football often came into the lives of boys well before they began high school. That American children appeared to be less physically fit than their European counterparts made matters more urgent to legislators determined to project a manly, mighty image abroad. In 1954, as Bachynski explains, a study showed that nearly 58 percent of Americans aged six to sixteen—compared to under 9 percent of Europeans—failed one or more of six strength and flexibility exercises. The study’s findings were presented—at a luncheon hosted by President Eisenhower (himself a former West Point tailback)—less like the work of medical professionals than of ideologues in an ongoing culture war.

Advertisement

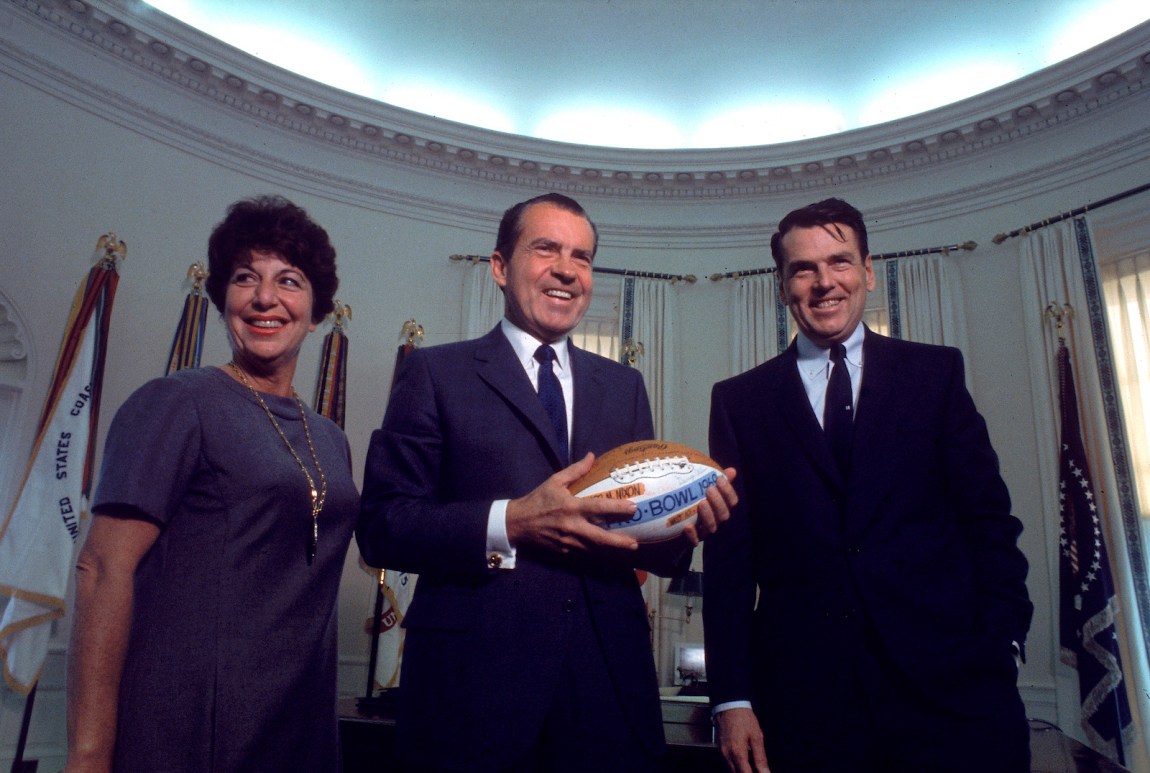

“American mothers are afraid of their children hurting themselves,” said Bonnie Prudden, to an audience that included Vice President Nixon and the baseball great Willie Mays. “This is a Band-Aid society. If a child breaks an arm, the arm may be in a plaster cast six weeks. That is not a catastrophe. The catastrophe is that so few opportunities for adventure remain to children—and the few that do remain are often curtailed by overanxious parents.” One is reminded of the overindulgent Lucille in My Son John, holding tight to the silver cord, unintentionally driving her son to sedition. Prudden’s coauthor, the physician Hans Kraus, added that Americans were now “paying the price of progress.”

Eisenhower responded by creating the President’s Council on Youth Fitness, of which Nixon, another—and lesser—former college football player, was made chairman. “I believe that competitive body contact sports are good for America’s young men,” said Nixon in 1958 at a luncheon for the American Football Coaches Association. Three years later, in an address to the same group, Attorney General Robert Kennedy described football as a testing ground for the qualities required of soldiers in combat. Half of American prisoners of war in Korea had died in captivity, Kennedy explained. He blamed this unusually high mortality rate on soldiers who “cared only for themselves, allowing their sick and wounded to go untended and die in the cold.” “Except for war,” he added, parroting similar statements made by his brother John, “there is nothing in American life which trains a boy better for life than football.”

*

One particularly effective engine for this idea was televised professional football, which arose as a national phenomenon in the early 1960s, when around 80 percent of American households had a television and color broadcasting began to emerge. In 1961, after NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle struck a deal with CBS to sell the league’s broadcast rights collectively, with profits shared equally among the league’s franchises, the Department of Justice filed a civil suit claiming the agreement violated antitrust law. Rozelle successfully lobbied Congress for an antitrust exemption, arguing that such a contract was necessary for Americans to be able to watch football on television anywhere, each week, without fail. Later that year President Kennedy signed into law the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961. It authorized the NFL and other professional and amateur sports leagues to sell their television rights as a whole, further enshrining government as an accessory to professional football in policy as well as in spirit. The NFL’s first broadcasting agreement with CBS was a two-year deal worth $9.3 million; its most recent one, negotiated in 2021 with five separate television networks, CBS, NBC, Fox, ESPN, and Amazon, totals roughly $110 billion over eleven years.

But it was football’s mediated presentation—grandiose but orderly, with innovative, sophisticated camerawork that sold the game simultaneously as a combat sport and an ultramodern ballet—that most effectively distinguished it from anything else on television. Where televised baseball, as Marshall McLuhan once argued, centered the individual encounter between batter and pitcher, football evoked a sense of pageantry and purpose: twenty-two men, eleven on each team, following only their specific orders, on each down, in service of the greater whole. That they could all be seen acting in lockstep from one aerial camera angle gave the game its patina of fraternity and order, and made football the perfect vanguard of a young medium.

When you zoom in, as television cameras do, order descends into honorable chaos, underscoring the grit and physical sacrifice of the athletes on the field. Limbs bending awkwardly in the pileup, cold breath wafting through facemasks, the distinctive crunch of one helmet hitting another: these were the sort of sensory details only television could provide. They were vibrantly dramatized in the promotion of the sport by TV networks, which would soon pioneer the pre- and post-game show, and the league’s in-house film studio, NFL Films. Founded in 1962 by Ed Sabol, who had served as a rifleman in World War II, NFL Films was the league’s public relations branch as much as a film and production studio, repackaging in-game highlights as works of cinema, setting hair-raising collisions to the sound of gruff, heavy-handed narration and the majestic rise and fall of an orchestra. The game’s roughness was precisely the point, a sort of litmus test, as the Yale University dean put it decades earlier, for the “real man.”

Where broadcasts of professional games made godlike gladiators of these athletes, football for boys seemed to exist more reasonably—and safely—in the conveniently benign tableau of postwar suburban America. The historian and former NFL player Michael Oriard called the phenomenon “Football Town,” for the scenes of homespun, all-American camaraderie rendered cheerfully in newspapers and magazines at the time.3 In many of these depictions, football is a family affair: son is on the gridiron, his helmet endearingly oversized; often Dad is coach; and Mom supplies snacks from the sidelines, lest she upset the peace by worrying about bumps and bruises. Always, it provides an occasion for fellowship. “For the last two weeks of this muggy summer, 8-year-old and 9-year-old boys have been learning to play football while, only a few yards away, girls of the same age have been learning to be cheerleaders for the Farmingdale Hawks,” began a 1973 New York Times profile of a youth football league in Long Island. “In Farmingdale, the parents who sit on canvas chairs and watch their children practice have only praise for the program,” the article continued, before describing how boys from opposing teams enjoyed hot dogs together after the game. “Let’s face it,” added one of their fathers. “It keeps them busy. It keeps them off the streets.” To a certain kind of American family, Football Town stood for a set of social relations that felt sturdy, modern, and reproducible.

*

By every measurable statistic, fewer boys play football today than they used to. Between 2008 and 2019, a period during which NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell testified before Congress about the league’s wanton concealment of the links between football and traumatic brain injuries, the number of boys playing football fell annually, from approximately 2.5 million to 1.9 million. It has become axiomatic to associate this decline with some broader reckoning on the part of the American public with the costs of the game, due in part to the suicides of beloved players like Junior Seau, who was discovered posthumously to have been suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy. But the NFL, despite its now well-documented attempts to obscure those costs, remains more or less unscathed as an entertainment product. The league accounted for eighty-two of the hundred most-watched television broadcasts of 2022, and college football was responsible for another five. It is hard not to conclude that Big Football, in its headlong commitment to the game’s stately and spectacular mythos, has effectively inured much of its enormous audience from the sort of moral calculus they might otherwise apply to their own children.

To sustain this cognitive dissonance, tragedy is woven into ready-made narratives of redemption and sacrifice. In the pilot episode of Friday Night Lights, based on the 1990 book by H.G. Bissinger about the local varsity football team in Odessa, Texas, quarterback and prospective five-star recruit Jason Street takes a hit in the season-opening game that paralyzes him from the chest down. As his teammates surround him, kneeling in prayer, doctors tend to Street on the field. His backup, the unrehearsed anti-jock Matt Saracen, miraculously steps in to complete a ten-point comeback, scenes of which are interspersed with glimpses of the operating room where surgeons drill through Street’s helmet and pads to save his life.

That scene rhymes grimly with the most salient one of the 2022 NFL season, when members of the Buffalo Bills and Cincinnati Bengals stood by despairingly while EMTs worked to restore the heartbeat of Bills safety Damar Hamlin on the field last month. Hamlin suffered a cardiac arrest after a hit in the game’s first quarter and was taken in an ambulance to Cincinnati Medical Center after nine long minutes of CPR, during which a morbid and unfamiliar silence fell over the fans in Paycor Stadium. ESPN broadcasters, obviously stunned, acquitted themselves well, expressing empathy, shock, and displeasure. For the most part they refused to seriously entertain the resumption of the game or the negligible implications of its suspension, though ESPN’s Joe Buck dutifully repeated an edict, reportedly from NFL officials, that the players had five minutes to warm up before restarting, which the league now denies it issued. Were it not for Bills coach Sean McDermott and Bengals coach Zac Taylor, who spoke privately on the field before sending their players back to their respective locker rooms, Monday Night Football might well have continued.

Back at ESPN’s New York studios, viewers were treated to a barrage of well-meaning but not entirely truthful platitudes. “We play a violent game,” said former player Booger McFarland before distinguishing between what had just taken place and the less immediately life-threatening but still constant realities of fractures and concussions—the shock of which football fans metabolize more easily, perhaps because broken bones seem like a cost of business and the effects of concussions take root long after the broadcast has ended. Another commentator said the league was in “uncharted waters.” Adam Schefter remarked that an event as serious as Hamlin’s cardiac arrest had “never happened” and that he could not recall an ambulance on a football field during a game, while Suzy Kolber added, “I can’t really remember seeing players openly cry.”

Over and over, newscasters belabored the supposedly unprecedented severity of Hamlin’s trauma, rather than the more sobering fact that the NFL had greeted many previous instances in which athletes’ lives were threatened by football—most often by slow, painful neurodegeneration—with either knee-jerk subterfuge or hokey demonstrations of unity. By week eighteen of the season, once Hamlin had fortunately awoken from sedation, the nightmare had been cynically digested and then excreted by the league as a celebration of life and fraternity. “This weekend,” Goodell wrote in an open letter after Hamlin’s condition had improved, “players and coaches from all 32 teams will wear ‘Love for Damar 3’ t-shirts during pregame warmups in a league-wide show of support.”

While Hamlin remained in critical condition President Joe Biden visited Hamlin’s family in Cincinnati, voicing vague concerns about the sport’s dangers. And at the NFL Honors ceremony in Phoenix this week, the annual end-of-season awards presentation, the first responders who saved Hamlin’s life were trotted out before Hamlin himself joined them on stage. It felt alternately poignant and exploitative, like much of the league’s vainglorious, self-exonerating stunts. This time there will be no presidential intervention, in part because—thankfully—Hamlin survived, but more significantly because there are no more reforms to be made, at least in the name of player safety, that would not undermine the very principles on which football and its powerful proponents staked the game a century ago: heroism, self-sacrifice, independence, and interminable, unchecked growth.