I recently texted a friend that the prose of Renee Gladman “makes me feel that there is a level of reality that I can love, trust, and accept—and that it is funny that I have forgotten about it.” Text messages are not usually the medium of my finest critical insights, but in this case I had stumbled on a way to describe a long history of awe at and delight in Gladman’s work. My friend replied that she, too, was dying to see Gladman’s current show of drawings.

Artists Space is an appropriate setting for “Narrative Magnitudes,” Gladman’s first solo exhibition in New York City. The nonprofit gallery, founded in 1972 as an alternative to commercial venues, focuses on artists whose interests move among media and elude easy characterization, as Gladman’s do: she has published as a poet, an essayist, and a fiction writer, and since 2006 created line drawings that play intriguingly with the limits of legibility. Gladman’s drawings trouble the eye’s desire for cut-and-dried distinctions between word and image, and pose broader questions about reading, writing, and what constitutes a successful act of interpretation. They display a seemingly inexhaustible array of graphic intensities: lacy scribblings, smooth arcs, word-like tangles, hermetic math. The overall effect is to displace everyday habits of meaning-making and spectatorship. Her works introduce the viewer to new forms of language, as well as the particular conditions that make them possible.

Because I first got to know Gladman through her poems and prose, I tend to think about everything she does in terms of syntax. What I admire most is her ability to simultaneously manipulate the visual qualities of writing and the time and space in which meaning is made. This is what I was trying to get at when I was texting with my friend: Gladman is one of a handful of living artists who can convince me that there really is a mutually constitutive relationship between words and the world that I need to get excited about, and puzzle over, and occasionally laugh or shout at. She disabuses me of the negative fantasy that language and phenomenal reality are caught in a hostile, never-ending staring contest.

It is, for example, impossible to feel anxious or alienated when reading a passage like the following, from Gladman’s 2016 collection of lyric essays, Calamities:

The sea moves but not in the direction of most things. I felt sure that most things moved from left to right or in the reverse. But the sea has an entirely other relationship to space; it seems to move backward, pushing at the end of it.

These three sentences occur in the midst of an at first abstract-seeming description of the experience of watching “nothing move slowly in and out of focus on a movie screen.” It’s not easy to narrate the subtle mutation of what looks like indistinct darkness in a film, but Gladman does: “I thought it was the night, I thought I saw telephone wires in the night, I thought I saw the bottom corner of the night curl up like a page.” Carefully she reveals an image of the sea, then a thought about how observing the sea might reconfigure our “relationship to space.”

This reflection is so enmeshed in the sentences that express it that we rediscover “the sea” and “space” at the same time as we rediscover that the sentence has both an extent and a sort of estuarial flow. Much as the sea seems to “move backward,” so a sentence causes the reader to accumulate sense in reverse, even as she reads forward: we need to recall the first words to comprehend the last. (Fans of Stéphane Mallarmé will be familiar with this sort of heightened attention to word order and ambivalent motion.) It’s not just the sea receiving descriptive treatment from sentences here, it’s sentences receiving descriptive treatment from the sea.

Gladman’s writing is frequently a two-way street of this kind. She is invested in the act of literary description, but she also uses the nature of the world to teach us about the nature of writing—a reversal of literary description’s standard rhetorical hierarchies. The adroit vagueness of her prose (“most things,” “most things,” “pushing at the end of it”), recalls Gertrude Stein’s love of repetition and plain language. The whole construction is deceptively simple, reimagining meaning as a physical space and sounding its edges.

*

Lest I make Gladman’s writing seem excessively technical I should explain that the problems of space and sense I have just outlined in miniature are addressed at a larger scale and with more explicit political implications in the quartet of slender experimental science fiction novels she published between 2010 and 2017, about a city-nation named Ravicka. In Event Factory, The Ravickians, Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge, and Houses of Ravicka an epic tale about translation and architecture unfolds. The Ravickians use a language that requires what English speakers would consider a nontrivial effort at precise, often whole-body movement. As a “linguist-traveler” who visits Ravicka in the first novel observes, “the simplest negotiations demanded some aspect of performance.” The gesture used to ask to take a shower is, for example, “famously misinterpreted,” given that it “requires a scooping motion that swings behind the person (whom you are asking) toward his rear end.”

Advertisement

Ravicka’s infrastructure, buildings, and social formations are disorienting both to tourists and to those born there. An unspecified crisis threatens the populace, and little is fixed: walls move and borders shift, and more general historical and narrative resolutions never arrive. One must simply keep going, trusting that these dramatic transformations can be survived through the exchange of words and other signs, particularly within artistic communities. (Many of the characters are writers.) The novels are a remarkable account of what it is to belong to a place, given that our first language is a system for establishing differences and values from which we never fully recover. Translation isn’t possible, but we have to do it anyhow.

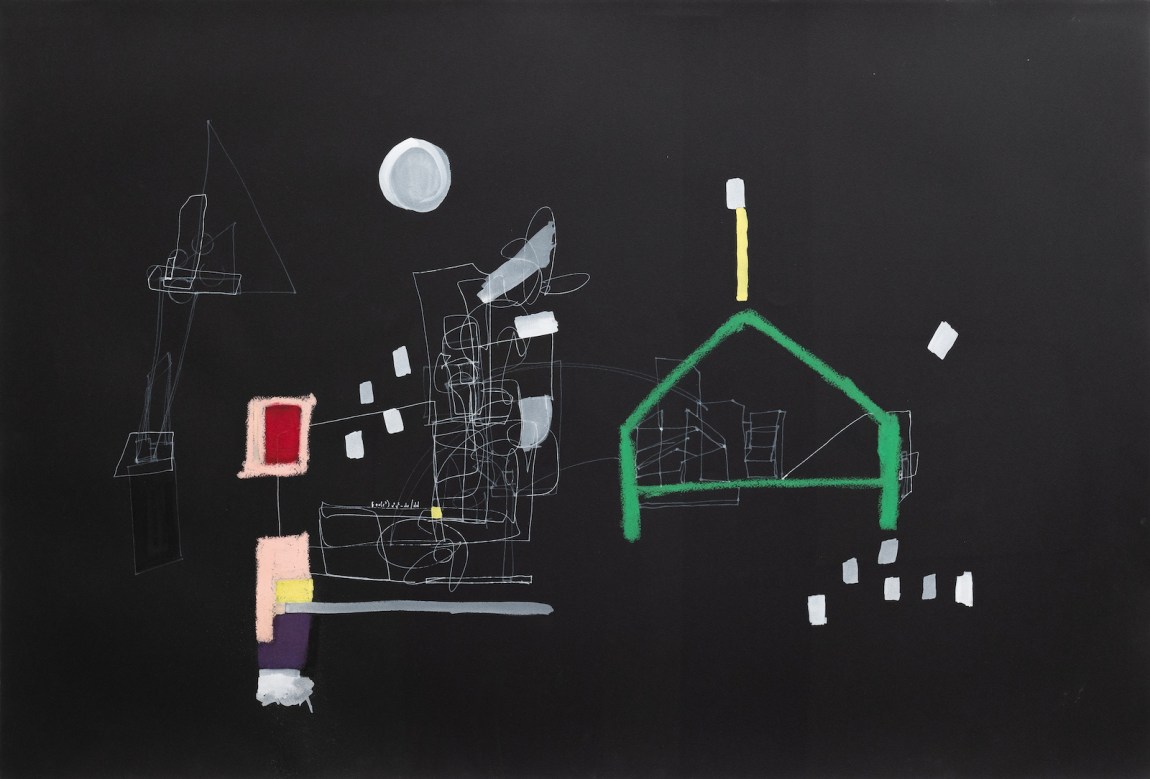

Gladman has also dispensed altogether with grids based on written characters and spaces. The “drawn writings” of her books Prose Architectures (2017), One Long Black Sentence (2020, in collaboration with Fred Moten), and Plans for Sentences (2022)—captivating, hand-penned forms that seem just about to transform into legible, semantic language but never do—are a bridge to “Narrative Magnitudes.” They look like city skylines or cross sections of catacombs, paragraphs or snarls of wire, maps of fairgrounds and airports. They are oriented at once toward the tropes and trappings of sentence-based meaning and those of schematic representation, but they also point the way into a zone between the two, a place of neither/nor and both/and.

“These sentences,” Gladman writes in Plans for Sentences, “will form a scaffold of ascending and descending clauses and will know space.” But then: “They will not know space.” The sentence cannot operate in advance of the logic it brings into being, and each of our attempts at expression comes with a nonsensical delay intimately related to what we hope to convey. What, Gladman seems to ask, would happen if a writer lingered in this weird limbo, making pictures of it?

*

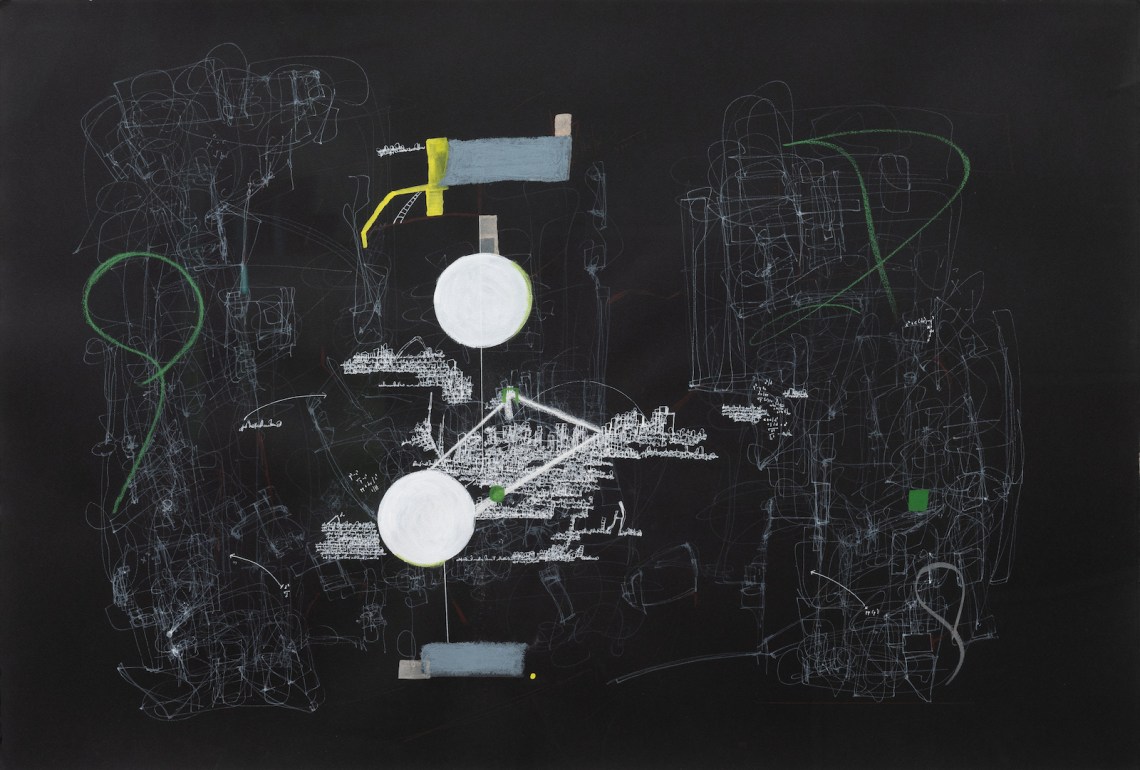

Reading Gladman’s literary texts will greatly increase the pleasure of standing in “Narrative Magnitudes,” but it is by no means necessary to be a completist to enjoy the show. As with the installations of the artist Hanne Darboven, another practitioner of asemic writing—script without semantic meaning—who liked to ask people to do something unexpected with their ability to read, the thrill here is in what you don’t yet know your mind knows how to do. The show consists of twenty-five works on paper, created from 2019 to 2022, hung on the walls of a single room. Many of the drawings involve white pigment on black paper. There are passages of bright color, too, a change from the drawn writings Gladman has published in books.

Gladman is also working on a large scale. Now one can bring one’s face into proximity with a materially rich and graphically detailed environment of traces arranged by her, at once getting closer to a sense of the hands that conceived these marks and sinking into a proliferation of inscription, doodling, brushwork, tracing, notation, planning, crossing out, erasing, calculation, and pointing. Like the Ravickians she invented, Gladman is deeply engaged with the affective possibilities of gesture. This is particularly apparent in the white pigment drawings, where the ink’s tendency to gather and thicken unpredictably carries an emotional charge. The white is sometimes translucent, revealing the dense black paper beneath, but in other places, even within a single thin line, we see layers, places where pigment has pooled. We note both the presence of the artist’s hand and the unusual dynamics of transparency entailed by white painting on a black ground, which differ from those of black ink on white paper. The drawings in “Narrative Magnitudes” indicate familiar habits of reading and looking but veer away from conventional resolutions. They resist the zealous interpreter’s art historical toolkit, favoring the eccentric qualities of handwriting over a lexicon of symbols and styles.

One of my favorite pieces in the show, Untitled (Moon Math), from 2022, involves a paragraph-like block of white script that reminds me of fine, crocheted yarn even as it also recalls inscription in stone. Gazing at it is a synesthetic experience. The white looping lines, which resemble a passage that might contain words, trigger something in my brain. I hear voices. As my eyes slide into other sections of the drawing I have more unexpected perceptions: circles bob convivially, and arrows point enthusiastically at variables arranged in equations I have difficulty parsing but nevertheless believe contain revelations about the functioning of the universe. Nearby, other marks seem to have been wiped away, perhaps to make space for a diagram that has yet to fully surface.

Advertisement

There is a simultaneously satirical and earnest, gentle grandeur to this work. It illustrates how hard it is to, convincingly, say nothing. Really saying nothing, it suggests, requires a preternatural comprehension of how sense forms, as well as a willingness to go into great detail. And yet I’m not quite sure that that is all that is happening here. It feels more like I’m being reminded that there is indeed a relationship to meaning-making, with all its delays and strange vectors, that I can love, trust, and accept—and that it is funny that I have forgotten about it.