Spring has been unusually noisy here in New England, more Stravinsky than twittering Vivaldi. Howling winds and honking geese in V formation usher in each abrupt change in the weather. Fighter jets from Westover Air Reserve Base scream overhead, training for World War III. Coyotes gather at night for their raucous karaoke. Our puppy gives me her “What the fuck is that?” look, her long ears twitching.

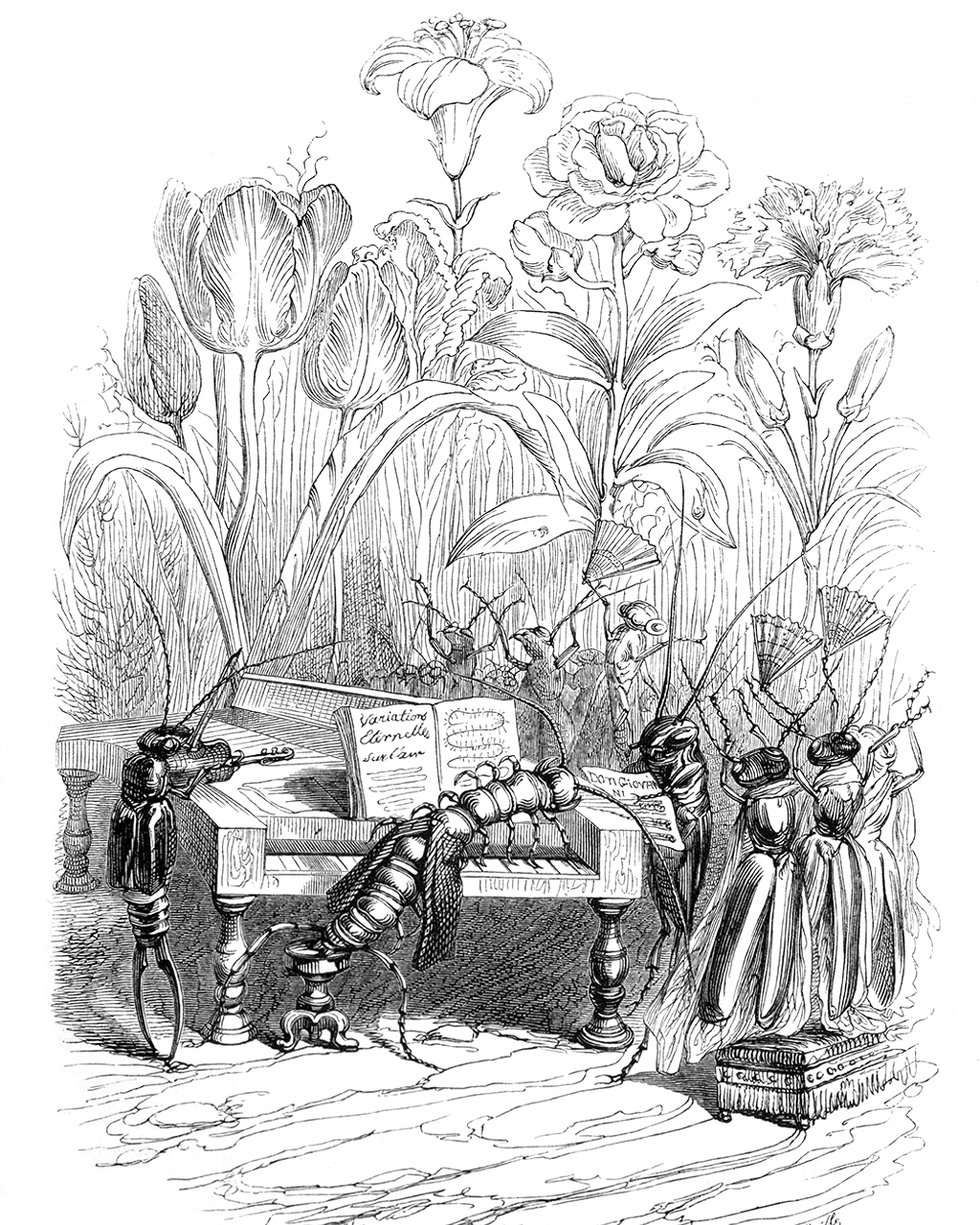

Spring just got noisier. A recent scientific study in Cell suggests that our seemingly mute plants are wailing too, especially when they’re cut or dehydrated. “Stressed plants make audible sounds that can be heard many feet away,” according to a glib article in The New York Times, “and the type of sound corresponds with the kind of bad day they are having.” We can’t hear them, fortunately, but their grievances are audible to moths and mice.

The news that plants are communicating about themselves made me wonder what they would say about us. “These rootless bipeds roam the world like tumbleweed, complaining incessantly. Viruses and language breed in their fertile mouths. Red roses aid them in mating, white lilies in dying.”

As Tiger-lily says about Alice in Through the Looking-Glass, “If only her petals curled up a little more, she’d be all right.”

Plant communication happens to be a thing in my family. My wife, Mickey Rathbun, is the garden columnist for The Daily Hampshire Gazette. She recently wrote about gardeners (like herself) who talk to plants. King Charles, she discovered, is an inveterate plant conversationalist, less skilled with human interaction. My brother Philip, based at Duke, studies how root cells communicate with each other.

According to researchers, plants thrive when talked to, or when music is played in their vicinity, whether Mozart or heavy metal. And when Emily Dickinson’s minor nation celebrates its unobtrusive Mass, apparently the flowers can hear the cricket chorus. A team of Israeli researchers confirmed in 2019 that flowers increase their nectar sugar to entice air traffic in their vicinity. “The wingbeats of flying pollinators, including insects, birds, and bats, produce sound waves that travel rapidly through air,” they observed, positing that “a possible plant organ that could relay the airborne acoustic signal into a response is the flower itself, especially in flowers with ‘bowl’ shape.”

Spring was ominously quiet when I was a kid, back in the heyday of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. I can remember the slow-moving truck at Myrtle Beach, where my grandparents would park their Airstream in the early Sixties, spewing a fog of DDT to kill mosquitoes. In the chapter titled “And No Birds Sang” in Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s phrase “the spraying of the elms” acquires the grim resonance of “the silence of the lambs.” You spray the elms with DDT to attack the nervous systems of beetles carrying Dutch Elm Disease, earthworms ingest the chemicals, birds gobble the worms, and everybody dies. Robins die; warblers die; the bald eagle dies, almost to the point of extinction. Oh, and the elms die, too.

“It was a spring without voices,” Carson writes. “On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.” For her book’s title (and also, I think, for its overriding mood), Carson was inspired by the lines “The sedge has withered from the lake,/And no birds sing” from John Keats’s “La Belle Dame sans Merci.”

I first encountered the gothic ballad in Jeff Campbell’s English class at the Putney School in the uneasy spring of 1972, when Nixon mined Haiphong Harbor. In her memoir, Hold Still, photographer and Putney alum Sally Mann describes Campbell as “a rotund, pipe-smoking, green-eyed black man” who encouraged her to read Absalom, Absalom!, thus introducing her to “the great sadness and tragedy of our American life” in general and the weight of race in her native South in particular. Unable to find a pulpit in lily-white Vermont, Campbell drove down to Dickinson’s Amherst, where I live now, to preach at the Unitarian Universalist Church.

I’ll be attending my class’s fiftieth reunion at Putney this spring. Reunions spaced five years apart have a way of telescoping one’s life: job, marriage, kids, divorce, retirement, illness, grandkids, death…

But hey, it’s spring, if still a little too cold for comfort. The forests are waking up, and so, if we’ve had enough coffee, are we. A friend of mine woke in the dawn light and realized he had forgotten to shut off his Merlin Bird ID app. He was astonished to find it had recorded a great horned owl. The song sparrows are “wound up for the summer,” as Elizabeth Bishop wrote in “A Cold Spring,”

Advertisement

and in the maple the complementary cardinal

cracked a whip, and the sleeper awoke,

stretching miles of green limbs from the south.