The child couldn’t tell the time. It was 1953, and she was looking up at the clock hanging on the wall in the vast, shadowy, central rotunda of her new school in Brussels, and couldn’t read the hands. Why she’d been asked to leave the classroom and find out the time is unclear; surely the classroom had a clock of its own—perhaps it was broken? That child was somber and earnest, eager to obey, keen to shine, and determined not to cry as she twisted one of her thin plaits round her fingers and stuck her thumb in her mouth, hoping someone would come and tell her the time so she could give her teacher what she wanted. Above her, the looming vault was entirely painted—a confusion of figures, gloomy and histrionic, soldiers, martyrs, angels in medieval clothes. She felt very small.

I was seven and newly enrolled in the Institut des Dames de Marie, a large Catholic school in a suburb of Brussels called Uccle. My father Esmond was a bookseller—we had come to live in Belgium because, after his bookshop in Cairo was burned down in the uprising of 1952, he had been made manager of the Brussels branch of W. H. Smith.1 My new school was an ample, imposing, freckled brick pile, Gothic crossed with Art Nouveau, with huge windows and a tall central porch leading onto the Rue Edith Cavell; it was a short drive from the house my father had rented for us. We weren’t far from the Grand-Place and central Brussels, on the Avenue de Fré, a long broad suburban street lined with substantial houses standing in herbaceous gardens. Ours had a barn where swallows arrived each summer to nest in the eaves. My father knew about birds, and the swallows made him happy; he built a bird table in the garden and recorded the visitors who came to feed there. A large predator raided one morning: a shrike! The excitement at this shark of the air—rare, handsome, cruel—was intense. The swallows, I was to learn, announced the turning season, timekeepers by instinct.

Telling the time that afternoon was complicated because I was only starting to learn French and even if I could have read the clock, I hadn’t yet learned to calculate backwards over the twenty-four hours in the French way, when twenty-to-four is seize heures moins vingt. I was also praying in French, and this is the side of my education that bears most closely on telling the time, on being able to picture the year turning, to know one day from the next. Daddy brought me home a missal, bound in pale calf, with a cross, a triangle, and the Holy Ghost descending embossed on the cover: Missel quotidien et vespéral, it says on its spine, and it has marbled endpapers and gilded fore-edges, over 1,500 pages of prayers and rites and lists of saints, including an appendix on Belgian diocesan saints, all of them very obscure. It is a bilingual missal, French and Latin, because those were the languages of the Sunday Mass which I attended with my mother and my sister. Daddy was an uncommitted Anglican but had kept the promise he made when he married my devoutly Catholic mother that he would bring up any children in the Catholic faith.

What I did not yet realize, as I stood baffled under the clock, is that time is not lived as points on a dial but as pictures in the mind’s eye, and those pictures are woven of experiences in language. Memory translates numbers into significant stories: the end-of-term, a birthday. A clock or a watch successfully imposes order on the tumult of life as it goes by, but le temps perdu and le temps retrouvé unfold in words and pictures—Proust’s magic lantern slides—not digits. The words “telling” and “teller” in English reveal how time translates into narratives, for as well as referring to narrating and speaking, they are used for counting, as in telling your beads, or bank teller. Chronicle contains the word for time, chronos. A journal, diary, or yearbook: all these forms of timekeeping are ways of storytelling, acts of language.

*

In Crowds and Power, Elias Canetti points out how the Catholic church, over its millennia-long history, developed methods of unparalleled efficacity in handling large groups; the calendar—the shared keeping of feasts and memorials—is one of them. Ideologies always have a stake in timekeeping, for radicals and conservatives alike. Augustus Caesar paid particular attention to the cycle of feast days, celebrating many personally in his role as Pontifex Maximus but also inaugurating many more, in this way consolidating his power. At the macro scale, be it in ancient Rome, Christendom, the Islamic world, imperial or communist China, the celebration of feasts and the memorialization of people and events play a part in governing the people. The ambition to name and control time also dominates at a more micro scale: heterotopias such as prisons, sanatoria, boot camps, religious cults, holiday camps, factories, alongside boarding schools and monasteries, necessarily impose a structure of time on their inmates and employees.

Advertisement

But this background in social conformism and coercion does not mean the practice cannot be adapted to help distinguish one day from the next more richly, more satisfyingly than what is offered by the arid numerics of the digital clock. Could renewed attention to ways of timekeeping enliven existence?

At some point a long time ago, I hid that Belgian missal behind some books. I didn’t want to see its spine on the shelves and remember those days of Catholic fervor. Yet near the start of the two years and more of the Coronavirus pandemic and the lockdowns, I began thinking about the way time was marked by feasts and holy days, how the dull everyday was translated into stories by the liturgy, and, in a flash, I remembered where I’d stowed my missal and fished it out unerringly. Did this rediscovery and my sudden renewed interest in the calendar mean that Catholicism was taking me back? Was I yet another case of “once a Catholic”…?

The answer is no—the message of salvation that the feast days communicate does not persuade me, yet the method of enlivening each day, of marking off the passage of time, strikes me as a way ahead. I now see a structure beneath the doctrines, like a watermark: the liturgical year is a very old way of timekeeping, from an era before watches and digital clocks, like one of those intricate and awe-inspiring orreries that reproduces the interrelated circlings of the solar system.

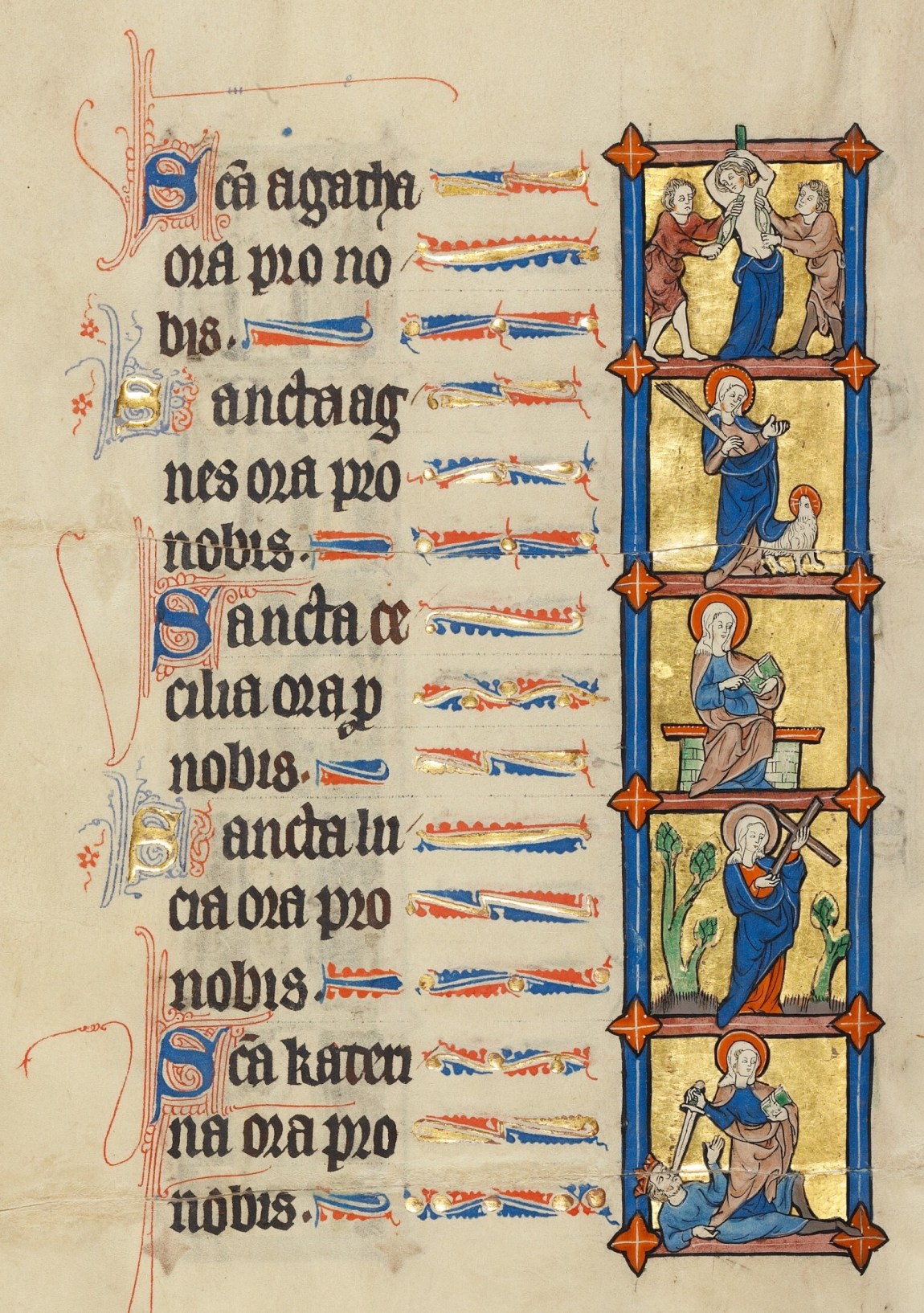

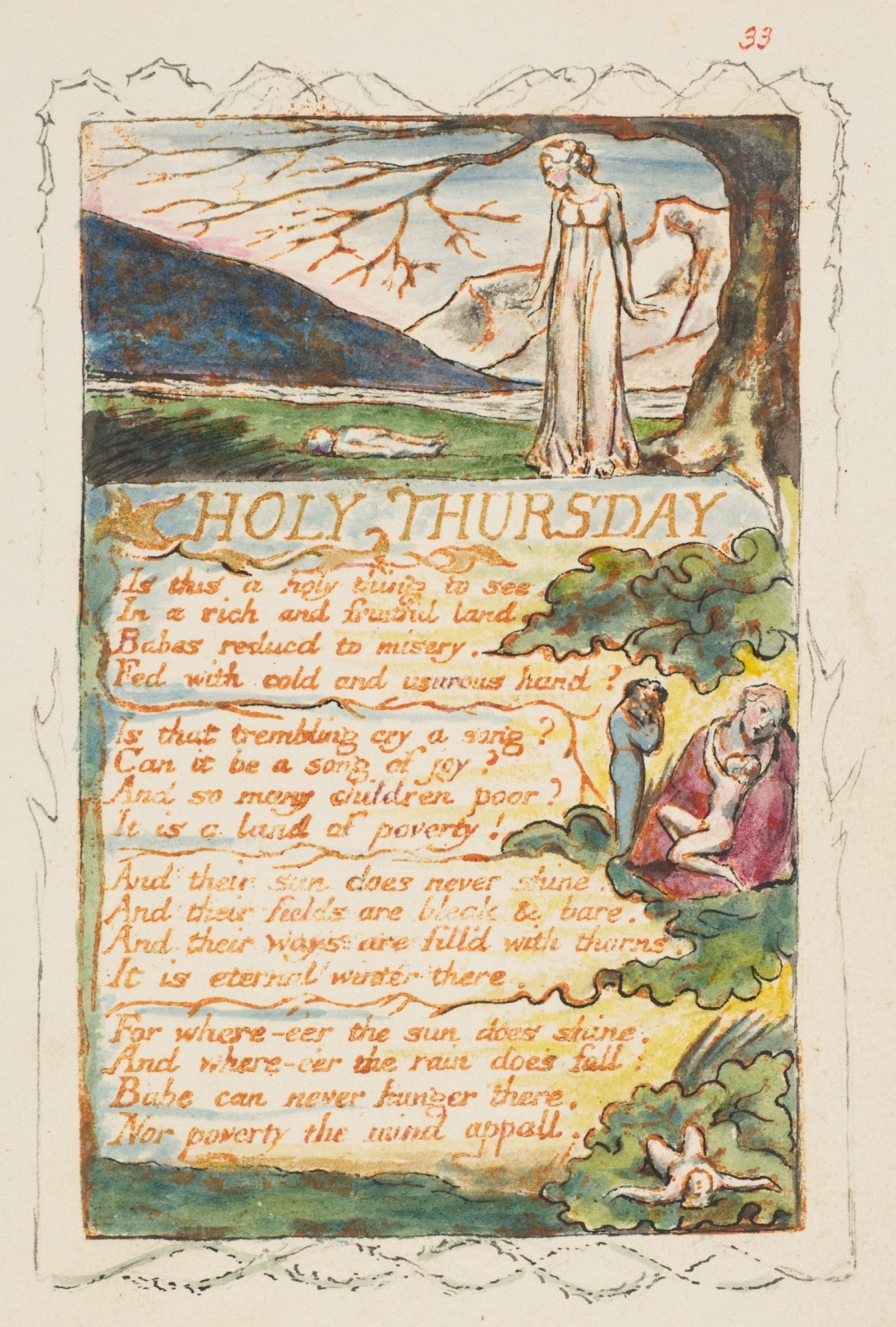

The cycle of temporale, the sequence of the offices or rituals for the moveable feasts, was braided into the cycle of sanctorale, the feasts kept on certain days, year in year out. The holiest days were picked out in scarlet by medieval scribes in their Books of Hours and liturgical calendars: red-letter days. Temporale gave out a changing rhythm: Good Friday, Easter, and Whitsun fall on different days from one year to the next. Together with sanctorale, which included such fixed feasts as the Annunciation, All Saints, Christmas, and all individual saints’ days, this calendar is mapped onto the old pagan festivals, just as state holidays in many countries now take place on days that were once sacred: May 1, the closing day of the Floralia in Imperial Rome in honor of the goddess Flora, became the feast of Labor and was later translated by the Vatican into the feast of Saint Joseph the Worker.

The daily rhythm of life in lockdown had a peculiar effect; we all felt it. Days slipped by, undefined, seemingly interchangeable. Another Sunday arrived hard on the heels of the one before. Yet, while time speeded up, it also slowed. It was as if Time weren’t wielding a scythe or wheeling about the heavens in a winged chariot but was accosting us—like an accordion player who stretches out the music in an infinity of wheezing, and then suddenly squashes his instrument tight and sticks there, in dumb and threatening silence. The identical days made them feel arrested; yet events that had taken place in 2019—the last visit to Italy, the last New Year’s Eve party—seemed sunk in the Jurassic strata of deep time. This monotony was shot through with dread that came and went, and still comes and goes with terrible intensity. Death was closer: for others, for me, as anguish at time disappearing would not be appeased.

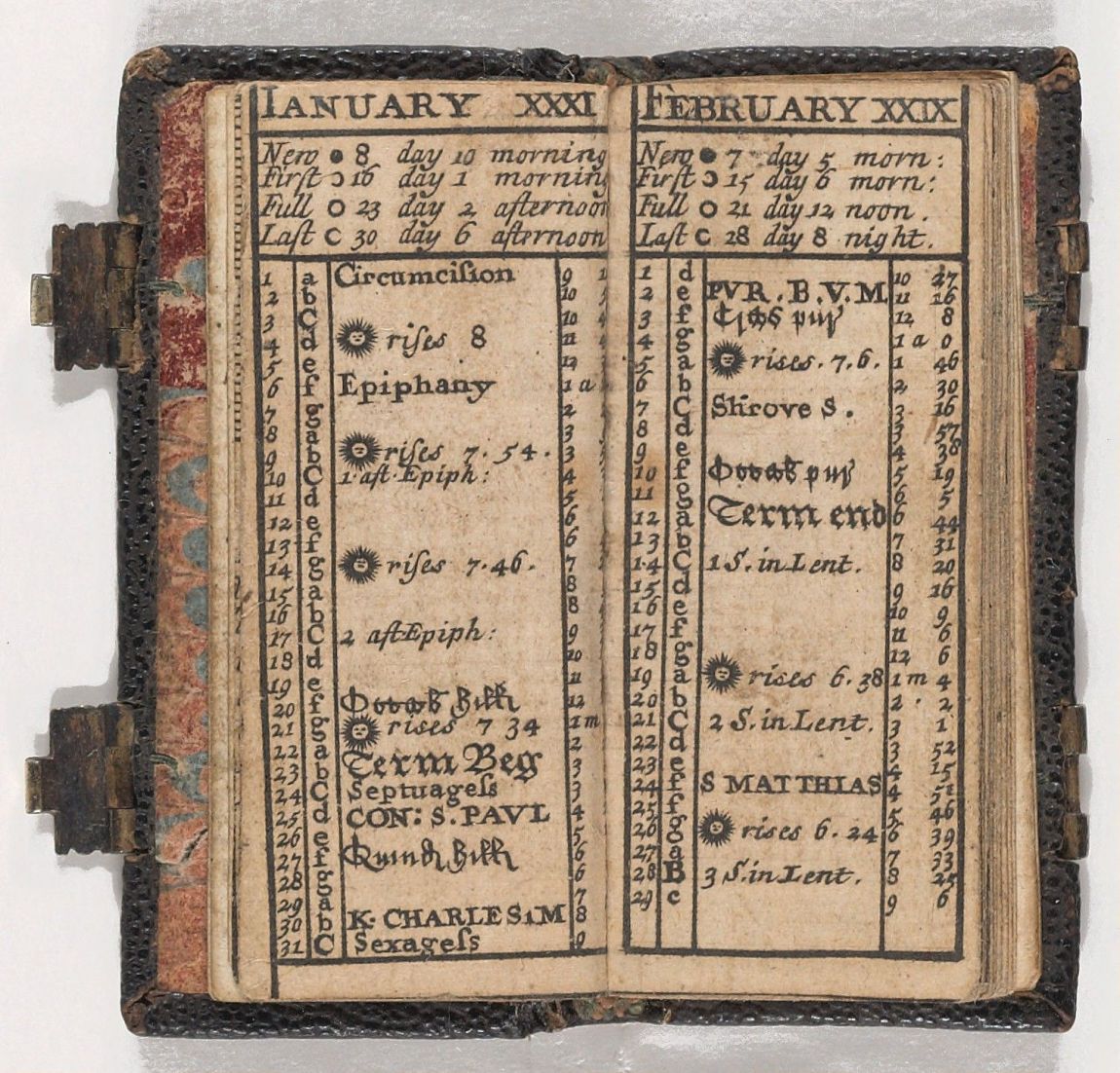

Gradually, over the long months, I became accustomed to the restrictions, and my experience of time began to change again. The sense of empty days disappeared; there was no longer any moment for tidying drawers or mending a broken chair. Only the fugitive speed remained: each day had gone—puff!—like a cartoon drawing of Bugs Bunny scooting off. The combination of this plague-stricken suspension—the new Covidian temporality—and the dread of worse just over the horizon gave new meaning for me to old forms of timekeeping: calendars, with their red-letter days and anniversaries, their high days and holidays and the sacred duet of temporale and sanctorale, and almanacs, with their reminders of feast days, cycles of the moon and the stars, and corresponding confident prognostications. Did the attachment of each passing day to a different event, miracle, or saint, help mark the endless repetitive flow, in the same way that a buoy out at sea will provide a landmark for sailors in the undifferentiated expanse of open water?

Advertisement

The daily lives of men and women and children enclosed in establishments such as monasteries, sanatoria, and foundling hospitals, or living and working on the land, needed these ways of measuring the seasons and the days to know where they were in time and space. Calendars and almanacs are time-maps, and apart from their survival today as gifts, they are a feature of a pre-digital era, superannuated: GPS knows where you are if you’re lost, and you can keep precise atomic time on your i-wear. But calendars and almanacs survive because they help to differentiate passing time. Our ancestors made schedules and charts to situate themselves, especially in relation to longer arcs of time than the local church bells or the town clock provided. It’s not surprising that a film called Everything Everywhere All At Once has just triumphed at the Oscars.

*

Picking up the worn missal of my Catholic girlhood and feeling it again, the squishiness of the binding (it is coming apart and there is foam backing under the leather), brought me up against that Belgian child I used to be. In 1956 the missal had traveled with me to St. Mary’s Convent in Ascot, Berkshire, where the services were still in Latin, which meant I wouldn’t be left out in spite of my prayerbook being half in French. I was terribly homesick, treated as an outsider because my English was formal (I had only spoken it with grownups and the speedy slang of my fellow boarders was entirely foreign to my ears, as they shouted “Bags I,” “Fains,” “Vamoose,” and “Quis? Ego!”). We pupils at St. Mary’s led the lives of little nuns, and my missal was in daily use; pages have fallen out from the middle where the ordinary of the Mass appears, for every morning we went to hear Mass and take communion.

We were woken by a nun entering the dormitory and, later, in the sixth form, coming into our own room, intoning “Dominus vobiscum,” to which from under the bedclothes we had to murmur “Et cum spiritu tuo” to show we were awake. After Mass, during which it was not uncommon for one of us to faint (we had to fast before taking communion), we went to breakfast where we stood for grace, which was pronounced before and after every meal. At 6 AM, midday, and 6 PM, the bells above the chapel rang the Angelus; twice a week, we went to Benediction, the evening ritual with prayers and singing, and on Fridays we made our confessions in the chapel, where one of the friars, in a dark box with a starry screen through which only his shadowy form was visible, would hear us—indulgently.

We also said the rosary, sometimes in the Lourdes grotto in the crypt underneath the high altar. The statue of Mary as she appeared to Bernadette, the young shepherd girl from the Pyrenees, stood in a niche among craggy rocks, all made of cork oak (“from the Holy Land,” Mother Emmanuel told us, in a reverent whisper) festooned with rosaries—beads made of cut glass, amethyst, or olive wood, which had been dedicated to Our Lady by others who had come to pray there before us. Owning a beautiful rosary caused fierce rivalry, but the mother-of-pearl, olive wood, and crystal varieties were expensive, and I never had enough pocket money for one. I made my own, with knotted string and wooden beads, and in the dark and cobwebbed rhododendron bushes that grew abundantly in the grounds of the convent I built myself my own grotto. I would keep my eyes tight shut while invoking Our Lady, and then open them suddenly, like a child playing peekaboo, to catch her before she could disappear. At “Holy Shop” (which alternated with “Sweet Shop”) I bought a plastic Jesus-on-the-cross that glowed; I used to take him to bed with me and read under the bedclothes by his light.

In Ascot as in Uccle, I was held in an unfolding drama and, within that overarching story, connected to a huge cast of people and their stories that were partly contained in that missal, stories often bizarre, bloody, human. These were the lives of the saints, one of whom was remembered each day in that morning Mass. Sometimes they came in pairs (Peter and Paul, Cosmas and Damian) or even in very large groups (Saint Ursula and her eleven thousand Virgins, all massacred together). Specific prayers followed from their status as Confessors or Martyrs or Virgin Martyrs, and the priest’s robes when he came in to say Mass would give us a clue as to which office in the missal we should use to follow the service.

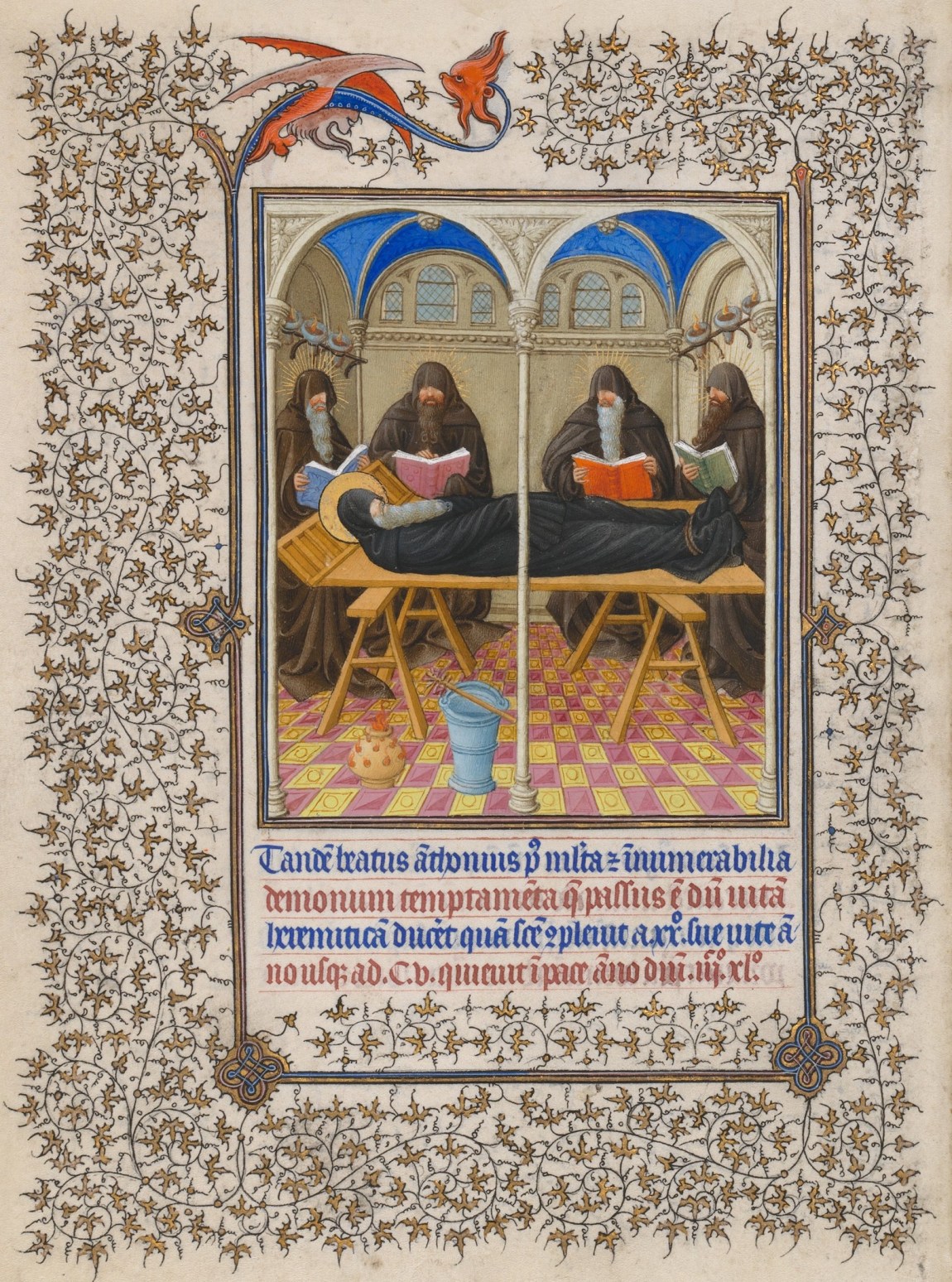

Sumptuous Books of Hours made in the Middle Ages and Renaissance recorded these feast days and saints’ days, weaving them into the unfolding agricultural year, with illuminations of monthly tasks, weather, harvests. Many such manuscripts are matchless and precious artifacts made for princes, such as the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry or the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, in which saints appear with their emblems (Saint Gertrude, who protects those who suffer from a phobia of mice, appears with rats and mice chasing around her; Saint Laurence, patron saint of chefs, carries the griddle on which he was roasted to death), richly surrounded by decorative borders and, in the lower margin, comic and grotesque doodles.

Did these glorious polychrome pages provide ways of overcoming the daily tedium? Only the rich could acquire these remedies against monotony, but the stories that inspired the illuminations weren’t behind a paywall. They were evoked in the daily Mass and would be picked up in sermons and pictures and gossip: the nuns at my school relished relating scenes of assault and vindication. In 1902, Maria Goretti (feast day July 6) was eleven years old when she was killed by a neighbor who had attempted to rape her; in 1950 she was canonized in the presence of her mother and her murderer. She was a favorite subject of our bedtime stories.

We tend to think of such stories as evidence of religious beliefs and rituals, but as Walter Benjamin points out in his essay “The Storyteller,” storytelling flourishes when men and women are imprisoned in repetitive tasks, shelling peas, preserving fruit, fulling cloth. “Boredom,” he writes, “is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience.” As the nightmarish twists and turns of the virus filled the news with futile information, different stories, outlandish, impossible, unverifiable, became a way of overcoming terminal ennui.

Aside from questions of historical veracity, the stories that fill the liturgical calendar are weird and startling, but they speak truthfully in the same way that a fable such as Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis does (and Kafka was inspired by local and Yiddish folklore). The freak-show qualities of some hagiography make it surprising that the depicted figures should be considered holy, but if you switch from theological expectations to look at their adventures as a desperate remedy for the drudgery, dreariness, and sheer misery of the daily grind, they become a kind of popular fiction, an offshoot of the fantastic. Arabic has a term for the literature of wonder—‘ajå’ib, which contrasts with the term adab, a category closer to belles lettres. Critics tend not to have thought of hagiography as a branch of literary fantasy, since it is written as true history and expects to be believed, whereas fantastic literature invokes a supernatural that is undecided and indeterminate, not divine truth. In contemporary culture, these boundaries are yielding.

The sequence of feasts is above all a cycle of stories, arranged into a mnemonic pattern. It may be thought of in terms of prosody, how scansion and rhyme add point to a poem, how memory can take the print of the lines more readily than a similar thought written in prose and lift a commonplace to the stars. (“Thus have I had thee as a dream doth flatter,/In sleep a king but waking no such matter.” “Wild nights—Wild nights!/Were I with thee/Wild nights/Should be our luxury!”) So too does the liturgy add personality to the quotidian: if in the Western world Mondays still have a certain feel, and Fridays likewise, due to the rhythm of an ordinary week, then the Mass we attended every morning as children and the songs we sang there added a particular flavor to that Monday, to that Friday, because when Father Alfred strode into the sanctuary in his sturdy old sandals under his silk and satin—red vestments meant a martyr, white a confessor (the celebrant might even be arrayed in rose, very occasionally, for specially joyful days)—we’d have to hunt at the back of our missals where the calendar listed lesser-known saints to find the right readings from the gospels for that day. The search was like a pinch, it could give a twist of interest to that morning. Ah yes, Saint Astius! Smeared with honey and stung to death by wasps.

Almost any day will yield anecdotes and memories—wonder tales. Saint Christina the Astonishing (died 1150, feast day July 24) rose from her coffin high into the air and lived on, performing feats which inspired her sobriquet. Saint Joseph of Cupertino also flew, in view of many witnesses and on numerous occasions—and he lived not so long ago (he died in 1663, feast day September 18). Saint Christopher sometimes appears with a dog’s head, like a victim of Circe’s enchantments, but in 1961 his authenticity was doubted, and he was expunged from the ranks of the saints as part of a major cull. (I remember how Sister Philomena cried when she was helping me at bath time, because her patron saint had been declared an archaeological error: an inscription on a sarcophagus in the catacombs had been misread. Philomena the child martyr, the patroness of babies, had become a figment, and the old Irish nun who cherished her was bereft.)

*

In a poem from her recent collection, Lurex, Denise Riley evokes the saints and martyrs she also knows, their stories and emblems. She closes with a question that is also a wish: “What hope is there of a purely secular grace?” Riley sounds skeptical, even despairing, that the secular sphere could ever be infused with grace.

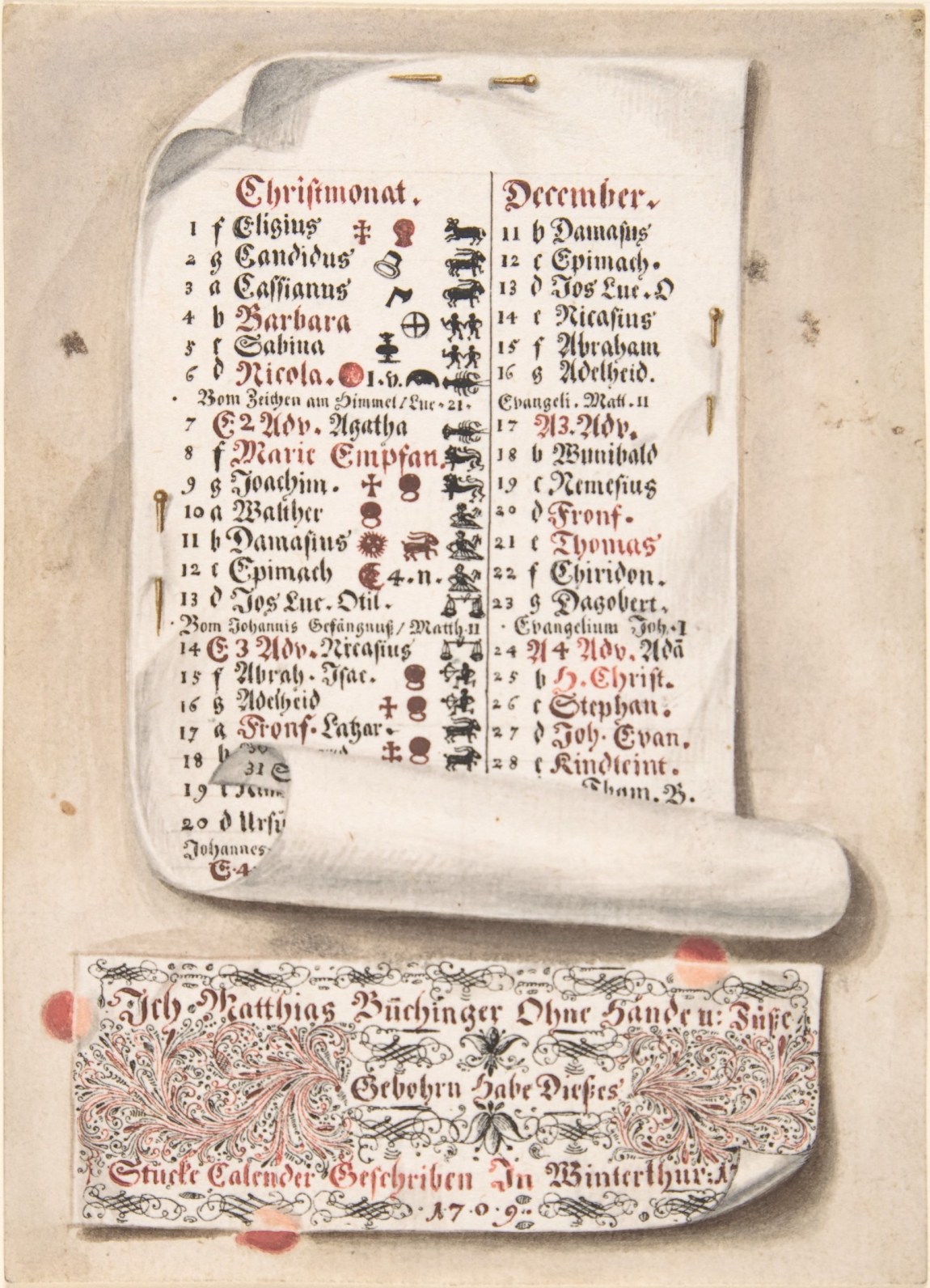

There have been attempts made; some of them tongue-in-cheek, others in earnest. For example, almanacs may be simply a kind of calendar, offshoots of Books of Hours, but they serve the locality in which they circulate and are alert to place and its particularities. They also tilt their vision away from repetition of past cycles toward future prospects, weather-forecasting and prophecy, horoscopes, recommended times for sowing and harvesting: almanacs entail prognostication. This is a crucial distinction between almanacs and religious calendars. Their heterogenous contents are traditionally a range of astrology, medicals nostrums, charms and remedies, portents and warnings—in sum, folklore, or “superstition.” When print made possible the wide distribution of almanacs, they became a dominant element of early commercial literature, typically carrying notices of auctions, fairs, livestock sales, suppliers, trades notices, small ads, and later, sports statistics. Their supernatural is not official religion but magic and divination, signs and wonders: an almanac predicts eclipses of the moon, the transit of Venus, meteor showers, and other less ascertainable phenomena. They are less hegemonic, more personal. To each their own almanac!

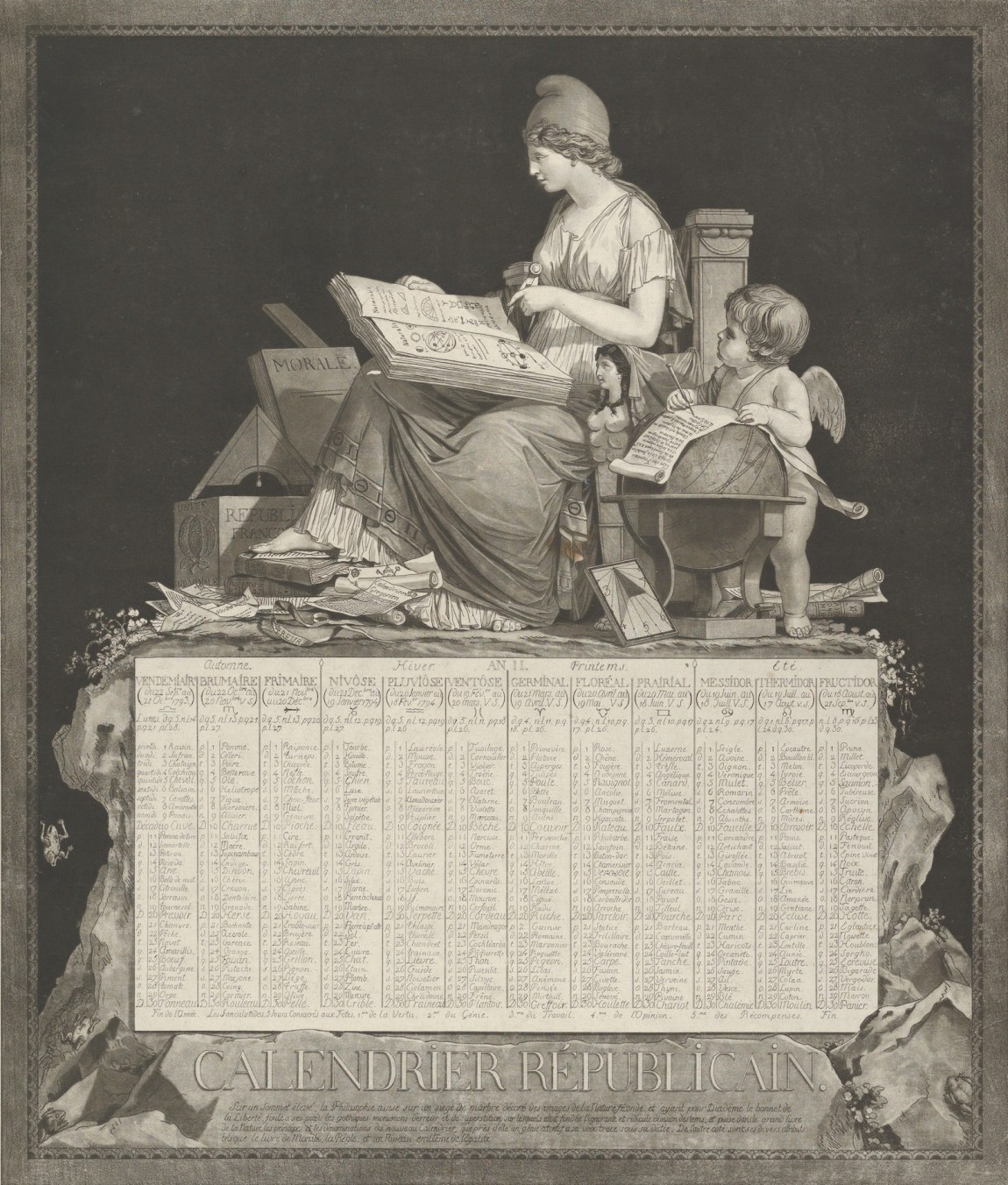

In 1793 the French government combined the pastoral almanac with the calendars’ collective memorialization; it set out to reinvigorate Time by inaugurating the Revolutionary Calendar. Theirs was a move analogous to adopting the meter as the fundamental unit of measurement; the power to determine such measures was considered divine, and an attribute of supreme authority on earth, symbolized by the rod or tally stick carried by deities in Sumer, Ancient Egypt, and Persia. It was also a gloriously extravagant and literary undertaking. Ten-day weeks (décades) in groups of three for each of the twelve months formed the main structure, leaving five days over for designated special feasts. A Fête de la Révolution was to be held every leap year. Philippe-François-Nazaire Fabre, actor, poet, and playwright, was appointed rapporteur to the committee charged with devising the new Calendar. Flamboyant and improvident, Fabre had done time in a debtors’ prison but had emerged, in 1793, as one of Danton’s right-hand men. He had added “Églantine,” the French word for honeysuckle, to his very ordinary surname, after he took part in the annual Jeux Floraux in Toulouse, a joust in which poets competed with one another. His sonnet to the Virgin Mary, the set topic, did not win, but it is a sign of his panache that, thinking he should have won, he adopted a spray of honeysuckle as his emblem and had himself portrayed carrying a silver replica of the flower.

The poet André Chénier and the artist Jacques-Louis David also contributed to the plans for the new regime’s timekeeping. They decided the months were to be called after French weather: the year began on September 22 with Vendémiaire, after a word for the grape harvest; Brumaire, foggy, followed, then Frimaire, frosty, then Nivôse from Latin for snowy; January was renamed Pluviôse, rainy, followed by Ventôse, windy; spring began with Germinal, followed by Floréal, and Prairial; summer included Messidor (from another word for harvest), and Thermidor from the Greek for heat and gift combined. The close of the Republican year, corresponding to August, was called Fructidor.

Fabre d’Églantine and his colleagues took their task into every corner of French bucolic life. They gave each day its own name, after the country’s flora and fauna, its raw materials and crafts and trades. The first day of each décade is named after a flower, fruit, crop, herb, or substance found at that time of year; accordingly, the spring opens with Germinal and the primrose, whereas the winter lists fuel and other raw materials—peat, coal, bitumen, sulfur, saltpeter, granite, marl, lime, gypsum. The fifth and the fifteenth days are named after a domestic or wild animal found throughout la France profonde (not forgetting fish and fisherfolk); the tenth and the twentieth days invoke gear and tackle and tools. The range is eccentric and the effect festive, successfully celebrating the ideals of the Revolution while dignifying the lives of the workers.

Fabre d’Églantine went to the scaffold, alongside his friend Danton, the year after his Revolutionary Calendar was adopted, on April 5, 1794—16 Germinal, Laitue (lettuce). Chénier was beheaded, too, on July 25, 1794—7 Thermidor, Armoise (mugwort). The system they had devised lasted another ten years, but in 1805, during the Directoire, Napoleon announced a return to Gregorian timekeeping—every day having a different name was unworkable. The Commune reintroduced the Calendar in 1871, but the attempt lasted only seventeen days.

A retort was issued in the 1880s, when the pataphysicians, an anarchic experimental group founded by Alfred Jarry to pursue “the science of imaginary solutions,” began dreaming up an alternative, absurdist calendar; a final version was adopted in 1949, the year after Jarry’s death. It consists of thirteen months, each twenty-nine days long, the twenty-ninth being imaginary and the thirteenth always falling on Friday. A high-spirited, profane parody, it mocks Christianity’s sacred cycle as well as state pietas. The months have loopy, idiosyncratic names, some of them after private obsessions of Jarry’s (February 22 to March 22 is Pédale, for his love of cycling). One month (October 6 to November 2) is called Haha; another (December 29 to January 25) Décervelage (Disembraining). A fundamental principle of the pataphysical philosophy is enshrined in the name of the month from March 23 to April 19: Clinamen (the Swerve).

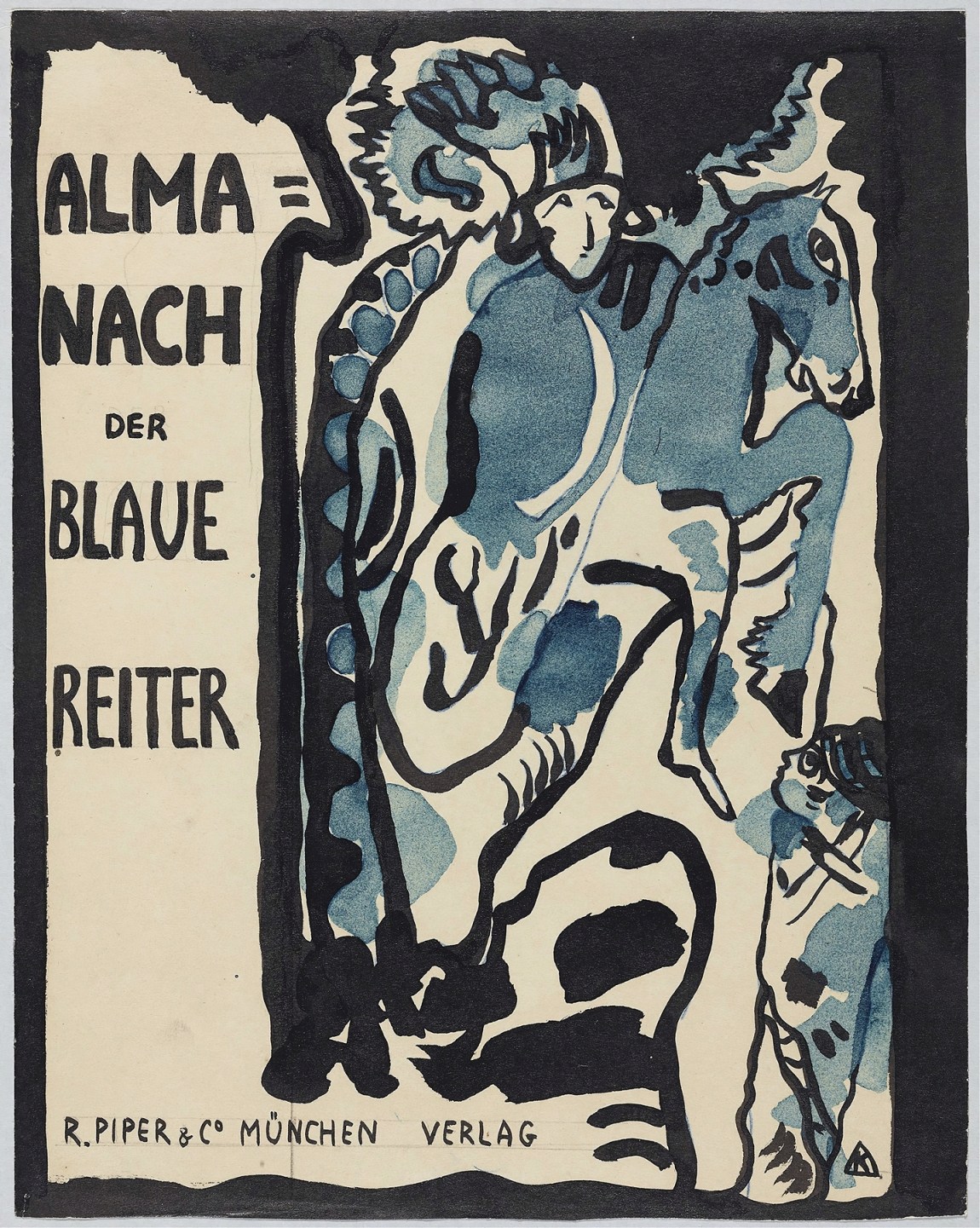

In 1911 the radical group of artists, writers, musicians, dancers, and thinkers who called themselves Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) proclaimed their own vision of secular timekeeping: “Well, I have a new idea,” wrote Wassily Kandinsky, “A kind of almanac (yearbook) with reproductions and articles…and a chronicle!…the entire year must be reflected; and a link to the past as well as a ray to the future must give this mirror its full life.” The artist Franz Marc became Kandinsky’s enthusiastic coeditor as they embarked on gathering visionary, provocative pieces by like-minded dreamers—in literature and music as well as the visual arts. August Macke, Arnold Schoenberg, and Paul Klee contributed, using the almanac as a platform for manifestos of their hopes and ambitions.

Their interests ranged widely and abolished aesthetic hierarchies: they laid a strong emphasis on vernacular culture—ancient Egyptian shadow puppets, Alaskan weaving, Russian folk art, glass paintings of saints and heroes from Bavaria, children’s drawings. Performance, storytelling, the fantastic, the ghostly, the supernatural, were never far from their minds. But the crucial aspect of their work is that their almanac—an eclectic display of artifacts, a call to cultural engagement, and a salmagundi of ideas, beliefs, and references—was making them into a community, even a movement. Compiling it, they joined friends, allies, comrades, and this fostered the intensity and productivity of their vision.

Drawing up a new calendar to suit a community still preoccupies agencies such as the United Nations. In the refugee camps they run, children and families observe a packed sequence of special days to commemorate struggles against illnesses (World Malaria Day) or to encourage various behaviors (World Handwashing Day). This calendar carefully avoids all religious or national references. It is regimenting but earnestly hopeful and inclusive (World Autism Awareness Day; International Mother Earth Day; International Birdsong Day). It aims at global acceptance, to be unifying and irenic. But it lacks the grain of the storyteller’s voice and the flavor of a place and the fun of stories, of fable, fantasy, individual memory, and inherited wisdom. In my lifetime, the thirst for feasts has been growing intensely, as the grounds for a community’s identity: Chinese New Year, and the religious festivals of Hinduism (Diwali), of Islam (the end of Ramadan) and of Judaism (Purim, Sukkot) are kept now with far greater visibility. And beyond the churches and NGOs, campaigns for memorial days, as for monuments, keep forming, some with great success: Pride month.

The relation between timekeeping and storytelling corresponds to the celebrated axiom of the Polish-American philosopher Alfred Korzybski: “The map is not the territory.” By analogy: the clock is not the day; the timekeeper is not the night. Korzybski meant that the accurate survey of a place does not convey the ways that place is experienced by the inhabitants who live there or travelers who pass through it, and that individual mental orientation charts a place according to many other factors besides the measurements of gradients and distances. Writers have frequently created characters and habitats, which, though they remain invented, are then written back into the fabric when invention eclipses reality: today, the city of Oxford presents itself as the setting of Alice in Wonderland and Harry Potter. Inventions overlay reality and reality gives way. As Borges writes in “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”: the truth is, reality wants to give way.

*

Can something similar be undertaken regarding time as we are living it now? The marking of time does not need to conform to a religion or a religious calendar or to an ideology commanding allegiance, not least as this would lead to even more interfaith tensions than are raging already in our conflicted world. But something richer and more personal could be built, closer to the keeping of birthdays and anniversaries, entangled with personal memories and connections. Like the Chinese, we could adopt a guardian animal for each year, not necessarily following the signs of the Zodiac, instead of the dry numbering we use now. The Ukrainians still have different names for the months: April is the month of Blossom, September, the month of Heather. In a new calendar, the old gods could be remembered haunting the new days; perhaps Friday, which used to belong to Venus and Freya, could still allude to love, passion, affairs of the heart. There is no end, really, of ways of enriching the daily round.

Certain dates still mean something to me, sealed into my sense of time from those stories and picture-memories of my childhood: December 6, la fête de Saint Nicolas, was kept in Belgium with more excitement and far more treats and sweets than Christmas itself. Bakers and pâtissiers and confectioners displayed trays upon trays of delicious vividly dyed replica fruits, strawberries, plums, bananas, oranges, pineapples, all made of pâte d’amandes, or massepain. But the date meant so much to me because San Nicola is the patron saint of my mother’s hometown, Bari. His body was brought there by a band of intrepid sailors who liberated this most precious of relics from the infidels then in power in Myra, in present-day Turkey. There San Nicola—who was to become Father Christmas—had left dowries overnight in the bedroom of three poor dowerless girls and, flying down over the storm-tossed waves, rescued the drowning from a foundering ship. In that part of southern Italy, Christmas was subdued by comparison with San Nicola or with La Befana, January 6, the feast of the three kings. This feast—Epiphany (la fête des Rois)—was celebrated in Brussels with a special galette in which a bean was hidden: if you found the bean in your helping, the gold-leaf paper crown from around the cake would be yours, queen for the day.

But calendar stories don’t have to be uplifting or jolly; they can also tell of old unhappy far-off things. They can pierce the punctum in memory. For me, May Day is mixed up with the scent of lilies of the valley: it was the custom in Belgium to exchange posies of muguets on that day. They were hawked on the streets at exorbitant prices and with their small white frilled bells and ecstatic scent, they were irresistible and we—my mother, my sister, and I—all wanted some. My father always fretted bitterly about money, and our nagging for a bunch of lilies of the valley set him off into one of his sudden terrifying rages. He was driving us to church when he began to bellow, then drove us straight at a cherry tree in full blossom, stopping just before he hit the trunk, my mother shaking and sobbing in the front seat.

One date I always notice when it comes around is November 22, Saint Cecilia’s feast. She is the patron saint of music, martyred in ancient Rome, who appears among the company of heaven playing her psaltery, sitting on a cloud. Much of the music we sang in the choir at school was composed by our Reverend Mother, Mother Cecilia, the heiress of the department store Marshall & Snelgrove, who had brought her immense fortune as a dowry to the convent when she took the veil. She died one term, when I was ten or eleven, and we were all taken to see her on her bier, white flowers piled around her, her face pale, her eyes closed, her white hands threaded with a rosary. I do not remember what the beads were made of, but certainly something precious. On Saint Cecilia’s day there rises inside me again the awe and horror I felt at my first sight of death.