A public memorial requires, at minimum, a shared memory—a consensus that something significant happened, if not necessarily what that something meant. The best monuments of remembrance, in fact, are those that inspirit collective emotion while accommodating disparate interpretations. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., evinces patriotic pride for some, renews rage for others. Yet the impassive wall invites the same gesture from nearly every visitor: to place a hand on it, to touch a few, if not a special one, of the 58,281 names inscribed there. Everyone can see their own reflection in the polished black granite.

The events commemorated by a public memorial, moreover, must have happened to a group—a tribe, a community, a nation—or created a group in happening. War memorials implicitly define the group by excluding those who are not of it. Critics note the absence from the Vietnam memorial of the three million Vietnamese casualties, including the US’s South Vietnamese allies in what they call the American War. One does not have to be the enemy to be the Other.

So far, the Covid-19 pandemic has satisfied neither of these criteria. Biology undermined solidarity. Politics killed it. Mutual protection meant keeping our six-foot distance. Some people—the uninsured, the incarcerated, the Black and brown, the expendable “essential” worker—experienced a different pandemic from those who waited it out in the Hamptons. The fellow-feeling and collaboration common during mass calamities—Rebecca Solnit’s paradises in hell—could not materialize. Even had the Trump administration not seized the crisis as another nation-fracturing opportunity, how were we to come together when we were not even allowed to breathe on each other?

Everything about the pandemic remains in dispute. We still do not know how it started or who, if anyone, to blame. We do not concur on when, or even whether, it ended. The Biden administration declared the national public health emergency over on May 11, three years after the red states began lifting restrictions on such necessary institutions as tattoo parlors and casinos, and President Trump congratulated the pastors who kept packing their churches as the virus raced among the parishioners. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that nearly 6 percent of US adults are still suffering from long Covid, and more than a thousand US residents are dying weekly.

Not all of us even agree that there was a pandemic. Almost 104 million cases were reported in the US and more than a million people died. If you live in a city where the sirens screamed day and night, you could not deny reality; 900,000 New Yorkers each lost at least three people they loved. If you spent the pandemic in rural Montana logging into Parler for intelligence, however, you may continue to insist that the whole thing was a hoax.

Some New Yorkers have erected permanent markers to the city’s fallen. One honoring the first sanitation worker to die of Covid made the rounds of department facilities before its fixed installation outside a garage on Spring Street in Manhattan. At Queens College, a commemorative plaque has been affixed to a stone. The online publication The City, working with some of the city’s journalism schools, is archiving the stories of the Covid dead.

But it makes a kind of sorry sense that the Covid-19 tributes being mounted by a New York collaborative of artists, folklorists, and community groups are intentionally “ephemeral”—made to live briefly, to fade and tatter, and to be dismantled after a month’s time. “Makeshift” is how The New York Times described an early installation, attached to a fence on the Lower East Side.

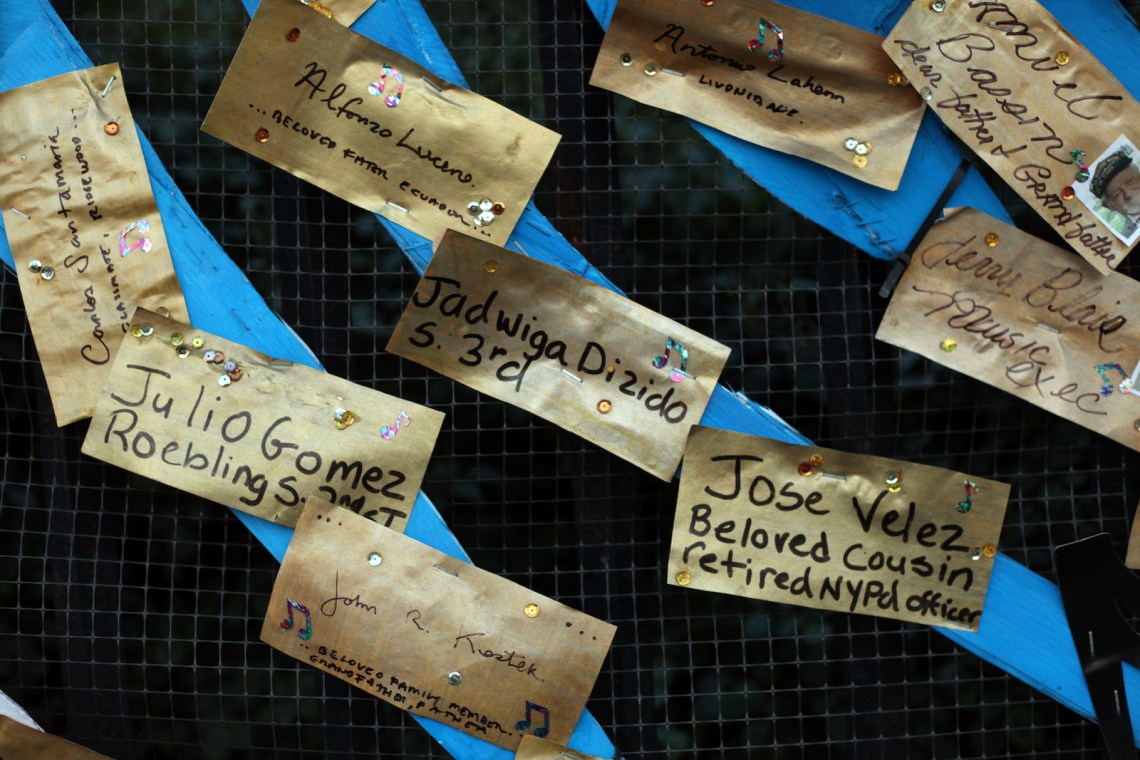

Naming The Lost Memorials (NTML), in collaboration with City Lore, Mano a Mano: Mexican Culture Without Borders, and the Bread and Puppet offspring Great Small Works, has been organizing open-source pop-up monuments around the five boroughs since 2020. On May 11, hours after the crisis officially expired, the project staged an “activation” of its monument to “The Many Losses From Covid-19” at Green-Wood Cemetery in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Winging from both sides of the main entrance at Fifth Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street and comprising handcrafted tributes contributed by twenty grassroots organizations, the installation covers about a half-block of the cemetery’s wrought-iron fence.

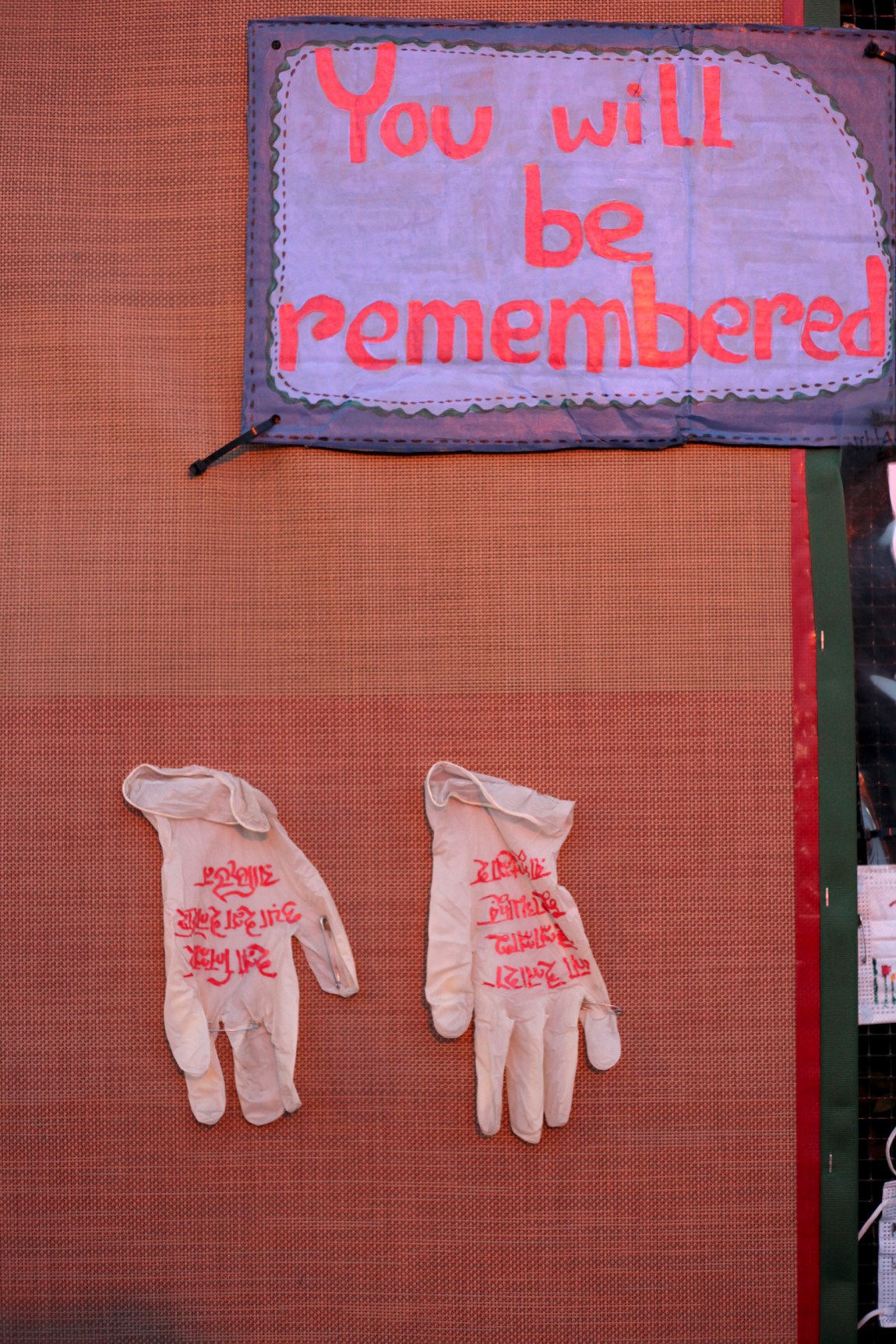

The population resting among the lush hills of Green-Wood is not half as diverse as the New Yorkers represented on the fence. The names and messages are in English, Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Arabic, and Hebrew; the words hope and love recur like a refrain simultaneously translating this babel of lyrics from every language to every other. Thin white cotton strips, with an invitation from the Jews of Color workshop to “name your loss on fabric,” suggest the simple shrouds of Jewish burial. Bengali characters in bright red, orange, and yellow, painted on quilted Kevlar by volunteers at the Bangladesh Institute of Performing Arts, recall the colors of Hindu funerary rites.

Advertisement

Hearts, birds, clouds, rainbows, butterflies, and people are crafted out of paper, string, popsicle sticks, plastic flowers, Kente cloth, and polyester. Hanging everywhere are blue surgical masks decorated with Sharpies. The masks on Yaffa Cultural Arts’ tree depict syringes stabbing buggy-green coronaviruses—no antivaxxers here. Everything is held to the mesh-lined fence with safety pins and plastic twist ties, as if to guarantee impermanence.

At seven in the evening, a crowd of about 150 gathered on the other side of Green-Wood’s double-arched, brownstone Gothic Revival gates. Swooping occasionally from the nest wreathing the central spire were the cemetery’s resident feral parrots, like neon-green jewels tumbling from a garish crown. There was an international contingent of drummers and a handful of banners: the Women’s Empowerment Coalition of NYC, held by women in hijabs; the Parent-Child Relationship Association, a community group for immigrant families in Sunset Park and Dyker Heights, Brooklyn.

Still, the “procession” to the Gothic-style Historic Chapel, just a few hundred yards away, was more like a stroll. Some attendees were dressed for a picnic, in T-shirts and shorts, some for a proper funeral, in dark suits or long white dresses and African print headwraps. One woman wore a tiara of green sequined streamers, a huge red fabric amaryllis, and a crest of spoons, the disability community’s symbol of chronic disease.

Outside the chapel, honored guests settled in the folding chairs facing the steps and the rest of us fanned out onto the shallow grassy amphitheater. Green-Wood’s cheerful curator of death education welcomed us to the Necropolis. District 38’s City Council member roused the assembled: “We are doing what our country failed to do! We are here because we love. We will keep calling out injustice!” A Guyanese preacher from Brooklyn drummed and chanted a libation—“Hello hello! Hello hello hello hello!”—pouring wine and water into the garden at the center of the oval drive and spraying aerosol fragrance into the air. We all shouted “Ashay!” A Gambian kora virtuoso in a gray embroidered kufi played and sang a prayer for long life, followed by an Israeli singer warbling a prayer for the dead and four Honduran women swinging linked hands to an Afro-Caribbean invocation of unity. Long Covid Justice gave a “litany of loss.” The prelude closed with “Let It Be.”

I sat behind a draped column and a barefoot girl with wings and a missing hand, the contours of both monuments relaxed by time and acid rain. As the sun set and the air chilled, I leaned against a new granite gravestone to my right, still as warm as day.

With little plastic tea lights in hand, we moved to the front, where Kay Turner, performance artist, folklorist and cofounder of NTLM, led a call and response. Naming the lost! Attendees shouted out their dead, a preponderance of whom were Hispanic. A family who had lost four members in one week paused after each name for the crowd to add its amen, Naming the lost! Next came the losses. “Employment!” Naming the losses! “Mothers!” “Sisters!” “Brothers!” Naming the losses! “Connection!” We filed past an altar heaped with silk and plastic flowers, placing the tea lights among them. The high wooden doors opened, and a mariachi band emerged. The horn blasted, the guitarrón sounded its big-bellied thrum, and women in stiff white dresses danced in a circle, fuchsia sashes aloft. It was hard to leap right into celebration so soon after all those names.

As I walked my bike past the fence, I noticed I was still wearing the N95 mask requested by the organizers. The smell of my breath inside it, the fog on my glasses dissipating, the fact that I’d forgotten I had the mask on—all pulled me into a past that is hardly past. Something glinted from the sidewalk: a safety pin. I picked it up and put it in my pocket. It would probably disappear into a drawer or the dryer.

I copied out the words climbing a cloth rainbow: Si después de esta pandemia no somos mejores personas, entonces no habemos apprendido nada de esta. If after this pandemic we are not better people, then we have learned nothing from it.