In the fall of 2021, as military forces from the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) swept south toward Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, they encroached upon a swathe of highland territory known as Menz. A blue-green land of deep ravines, terraced hills, and imposing flood basalts, Menz is sometimes seen as a place apart. In his classic midcentury ethnography of the area, Wax and Gold, the University of Chicago scholar Donald Levine observed among its inhabitants—most of them farmers of barley, sorghum, and teff—a potent mix of martial prowess and piety. This “land of fighting and fasting,” as he called it, served as the cradle for a dynastic line of Amharic rulers that included Menelik II, the founder of the modern Ethiopian state who dealt a shattering blow to the Italian colonial army at the battle of Adwa in 1896, and also Haile Selassie. It was hardly surprising, Levine noted, that the people of Menz proudly call their region “ya-negus agar” (the king’s country) and “ya-amara mentch” (the source of the Amhara).

When people there heard the artillery of the advancing Tigrayan forces, able-bodied men and women rushed to the front, while more vulnerable residents did what their ancestors had done countless times before during periods of war: they fled their villages for the shelter of one of the innumerable caves that pock the faces of the nearby mountains. But there was one cave in particular that they avoided, an expansive and seemingly impregnable cavern with a slit of an opening halfway down a towering cliff. Known as Ametsegna Washa, or the “Cave of the Rebel,” it has long been regarded by locals as a place of evil, haunted by malevolent spirits and by memories of a horrific act of mass violence that occurred here more than eighty years ago.

In the spring of 1939, Italian military forces under Mussolini used mustard gas to flush out a band of Ethiopian resistance fighters, their families, and civilians from surrounding villages who had taken shelter in the cave. The details of what happened next remain contested to this day, but well over a thousand Ethiopians—including women and children—probably died, either from the effects of the gas or during the summary executions that followed their surrender. Forgotten and deliberately ignored for decades, it is an event that, like the rest of the five-year Italian occupation, has cast a long shadow over a divided and war-torn Ethiopia. It has also sparked fierce debate in Italy at a moment of far-right revival and continuing denialism about the country’s colonial past and its brutality. Today the darkened chambers of Ametsegna Washa are still strewn with the detritus of the siege and the bodily remains of the lives it extinguished—a grim memorial that unequivocally refutes the apologists’ polemics.

*

One afternoon last November, I descended an escarpment that led to the cave, following a footpath made indiscernible in places by an underbrush of flowering thistle. To the left, the ground fell away to a vista of high plateaus and a winding river. A consort of geladas—the bleeding-heart baboons, so-called for the exposed patch of red skin on their chests—perched on a promontory.

There were just over half a dozen people in our party, most from Kambo, a nearby hamlet of zinc-roofed huts named after an Italian military camp. A militiaman joined us as an escort, slinging a bolt-action rifle across his shoulders. There had been peace in the area for over a year, and just days before my visit the TPLF and the Ethiopian government had signed a ceasefire in South Africa, ending a brutal civil war that is estimated to have been the deadliest conflict of the twenty-first century. Still, people here had little to celebrate. Years of erratic rains—the result of anthropogenic climate change—and soaring fertilizer prices due to the war in Ukraine were imperiling the food security and livelihoods of many. Violence had erupted between and within families over sparse tracts of tillable land.

Our guide was a fifty-year-old woman from Kambo named Elfinesh Tegene, who bounded down the rocky defile in thin-soled sneakers with an alacrity that left even the local men exasperated and exhausted. The daughter of a resistance fighter who’d survived the massacre at the cave, she had taken on the unofficial role of caretaker—a responsibility she regarded as something of a sacred duty. “It’s a living memory,” she told me. “We feel it’s a huge part of us.”

Approaching the cavern, she gestured to the two stone barricades on either side of its opening, which the Ethiopian defenders had used as firing positions in the early stages of the siege. “This whole valley was filled with dead Italians,” she said.

Advertisement

Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935 is widely seen as one of the events that led to World War II, undermining the already feeble interwar norms of collective security and the credibility of the League of Nations as a guarantor of peace. Buoyed by ambivalence in Western capitals and ineffective sanctions, the Italian fascist forces advanced rapidly across the vast country—a member of the League of Nations and one of the few places on the African continent not under European control. By May 1936 they had reached Addis Ababa, forcing Emperor Haile Selassie to flee into exile in England.

But Ethiopia was far from conquered. Even before their entry into the capital, the Italians had faced grassroots opposition from the Arbegnoch, or Patriots: Ethiopians of all classes, regions, and ethnolinguistic groups. Over the next several years the Patriots waged a campaign that included, among others, women, the Orthodox clergy, and a short-lived cadre of former military cadets and foreign-educated elites who espoused constitutional republicanism, rather than a restoration of the emperor. Facilitated by underground networks of spies, saboteurs, and message runners in cities and towns, the locus of the insurgency shifted to the rugged provinces north of Addis Ababa, where small, dispersed, and sometimes quarrelsome bands of partisans conducted hit-and-run raids and ambushes. The resulting war of attrition was exceptionally ferocious, marked by Italian reprisals in the form of executions, the burning of homes, and the destruction of crops and cattle.

Elfinesh’s father joined the resistance at twenty-five. By the time of the siege at the cave he’d already suffered gunshot wounds to his arm, legs, and head. He served under a formidable guerrilla chief named Teshome Shenkut, himself no stranger to violence and hardship: he’d lost two of his four brothers to the Italians—one of them decapitated—and would lose another before the war was over.

In late March 1939 an Italian reconnaissance plane tracked Teshome’s band of fighters to Ametsegna Washa. Within this troglodytic world, hundreds of Patriots and their families attempted to replicate the life they had lived aboveground. They slept and socialized in separate quarters. They ground coffee and cereals, cooked wat and injera in separate hearths, as custom required, and brewed a nutritious beer called tella. They drew fresh water from a large subterranean lake. When Italian soldiers appeared below the cave on the morning of April 2, the defenders inside thought they would be safe. They had ample stores of grain and livestock, and the cave’s narrow entrance was shielded by a stone facade and overhang. Any attackers, at least in the daytime, would expose their silhouettes to rifle fire.

Indeed, in the first few days of the siege, Italian troops fell under a withering fusillade as they tried to advance. The Italian officer in charge, a bushy-bearded colonel named Orlando Lorenzini, famed among his troops as the “Lion of the Sahara” for his part in crushing an earlier insurgency in Italian-ruled Libya, grew frustrated. Just a couple of weeks before he’d been handed a cable from Mussolini himself that demanded a conclusive victory, ordering that “no respite is to be given to the fugitives.” Lorenzini’s first idea was to employ a flamethrower to incinerate the denizens of the cave, but that device was quickly rejected in favor of a more complicated stratagem. On April 8 the chemical platoon of the 65th Infantry Division “Grenadiers of Savoy” arrived at Ametsegna Washa with a hundred artillery shells filled with arsine, a tear gas–like compound, and twelve jerry cans containing over two hundred kilograms of mustard gas that had been transferred earlier from a large aerial bomb.

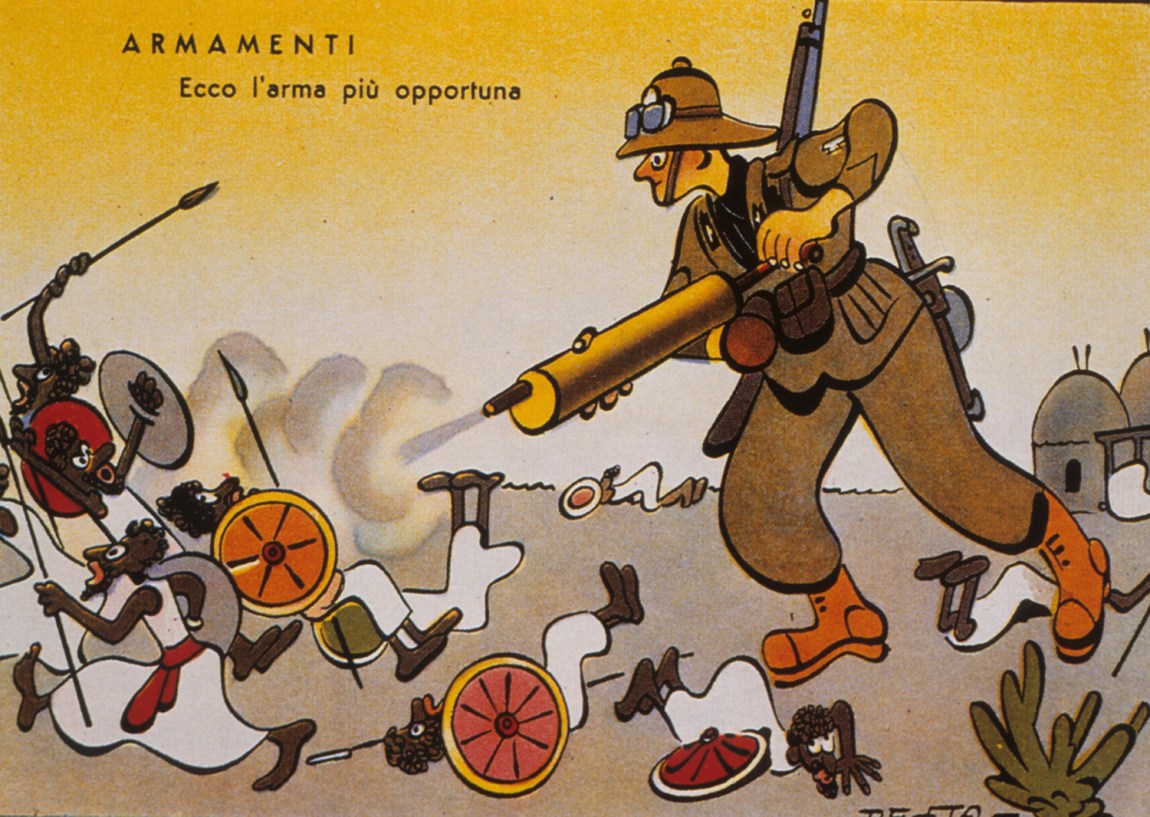

Chemical weapons like mustard gas and phosgene—banned by the 1925 Geneva Protocol, to which Italy was a signatory—had been integral to Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia: roughly 10 percent of all Italian munitions shipped to East Africa for the campaign contained poisonous gases. Throughout their war against the Italian occupation, Ethiopians would endure roughly five hundred tons of these toxins, often delivered via diabolical means: sprayed on their crops, livestock, and pastures, and dumped into lakes and rivers to punish civilians and deny insurgents resources. This rain of death, with its attendant ulceration of the skin—most Ethiopians fought barefoot—internal bleeding, and frequently lethal damage to the respiratory tract, only added to the panic inflicted by Italian airplanes and other mechanized weapons.

The night of their arrival, Italian troops from the chemical platoon ascended to the top of the cliff above the opening of the cave, hauling with them the mustard gas–filled canisters, to which they’d affixed lengths of steel cable and electric detonation cords. Staging the cans behind a pile of rocks, the soldiers hunkered down on foldable cots and waited in the windswept chill for dawn. At daybreak on April 9 the Patriots inside the cavern spotted what appeared to be a cluster of cylindrical objects being lowered by ropes before the entrance. They heard the distant report of artillery and then the boom of much louder and more proximate explosions, followed by gunfire. Thick clouds of smoke and yellowish vapors billowed toward them, filling their nostrils with a rancid smell like the odor of the senafich, or mustard seed.

Advertisement

*

Paces beyond the opening of Ametsegna Washa, the light vanishes. The cave ceiling quickly lowers to no more than two or three meters and the air fills with particulates from the chalky floor, making breathing difficult. Glimpsed in the gloom, my companions—hunched over and haloed by the light of their cell phones and torches—looked like a procession of pilgrims or supplicants, as if on a frieze.

With the release of the mustard gas, the Patriots closest to the opening fell to the ground and died immediately, according to testimonies I read and gathered. Others seemed to lose their wits and lunged for their weapons, threatening their fellows. Those that were not incapacitated or killed immediately retreated deeper into the recesses.

We wandered into the first of these chambers, one that was clearly used for the preparation of food and for cooking. There are stone mortars, fire pits, winnowing baskets, storage jars, and conical granaries called dibinit, fashioned from mud and straw. Some of these artifacts are still intact. Pushing deeper, we descended to the west, into the grotto of the lake. A colony of bats alighted, fluttering over the tea-green surface. Here the Patriots had gathered after the initial attack, attempting to overcome the ravages of the gas, wetting their eyes and cupping handfuls of water to their lips, to slake their thirst. But the fumes of the gas quickly reached this room and poisoned the pool. Not all of them gave up arms. That night, Teshome Shenkut and fifteen other fighters used diversionary fire and grenades to break the Italian cordon. Caught in the beams of the searchlights, some of the men died under machine-gun fire; others, including Teshome Shenkut, survived.

Farther along in the cave, the shadowed outlines of human remains came into view: skulls of varying sizes, mandibles with rows of molars, a ribcage, and a femur, draped in a decomposing garment. Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of eighteen people, including those of women and children. It’s a relatively small number of corpses, which corroborates the testimony of eyewitnesses: the vast majority of Ethiopian victims perished not inside the cave but outside, after they’d surrendered on the morning of April 11. Sickened, blinded, and faced with the pollution of their food and water supply, they had no other choice.

Based on her father’s recollections, Elfinesh related that the Italian troops separated the men and adolescent boys of fighting age from the women and small children. Tying the males together at the shoulders in groups of two, they marched them away from the cave. Her father was among them, and as he waited in what seemed to be an interminable queue, he turned to the comrade to whom he was bound and whispered, “This will not end well for us.” He loosened his binding and begged his companion to join him in fleeing. He was met with a shake of the head. Sprinting into the foliage, he managed to escape the fate that befell the others.

All told, about eight hundred Ethiopian men and boys were killed outside the cave, either by gunshot or by being pushed to their deaths into a deep canyon. “No rebel [has] escaped deserved punishment,” Colonel Lorenzini cabled to his superiors. He considered using explosives to collapse the opening of the cave because the stench of the corpses.

*

In 1941 the Patriots, along with forces from the British Commonwealth—including thousands of Africans conscripted from British colonial possessions across the continent—and colonial soldiers from Belgian Congo and Free French Forces defeated the Italians in Ethiopia and restored Emperor Haile Selassie to the throne. Over the next several years the Ethiopian government made a fruitless effort to bring Italian perpetrators of atrocities to justice, sending reams of documentation to the United Nations War Crimes Commission that detailed the use of chemical weapons, the bombing of medical facilities, and the slaughter of civilians.

The most notorious of the latter crimes were the February 1937 Addis Ababa massacre, in which an estimated 19,000 people were murdered, and shortly thereafter the killing of up to 1,600 monks and pilgrims at a monastery called Debre Libanos. Both were ordered by Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, the Italian viceroy of Ethiopia, already notorious as “the butcher” for killing tens of thousands of civilians in Libya. But not only were Graziani and other fascist figures in Ethiopia spared prosecution by Allied tribunals, some of them assumed leadership positions in postwar Italy. Historians have assigned much of the blame for this injustice to the governments of the United Kingdom and, to a lesser extent, the United States, which saw the fascists as bulwarks against communism. Another, no less compelling explanation is that the victorious Allies were eager to perpetuate the white-led colonial order and reluctant to sanction its upholders, however odious their conduct.

The horrors at Ametsegna Washa are scarcely mentioned in Ethiopia’s submission to the United Nations, save for a short testimony provided by Teshome Shenkut, who describes returning to the site after liberation to collect hundreds of skulls, which he deposited at the nearby church of Saint George. Among locals, meanwhile, the atrocity passed into lore and myth, handed down through generations. Few residents care to enter the cave for fear of the kifu menfes—evil apparitions whose breath, it is said, will extinguish the candle of any transgressor and make them lose their way in the darkness. The surrounding region is cursed as a “land of blood.”

Aberra Moltot, a white-haired, bespectacled nonagenarian, remembers these stories well. Born not far from the cave, he was seven at the time of the massacre and lost his eldest brother, two of his uncles, and his paternal grandmother to the Italians’ gas and bullets during the siege. We met in Addis Ababa in the high-ceilinged piano bar of the venerable Taitu Hotel, Ethiopia’s oldest lodge, founded in 1905 by Empress Taitu, the third wife of Menelik II. Like most Ethiopians, Aberra distinguished between the fascists and the Italian people. Still, he is astonished that Italy, a Christian nation, could have committed such savage acts. He recalled the unremitting hunger of those years and the Italians’ attacks on villages. After the war he became a teacher. A steady climb through the ranks of the provincial and national bureaucracy followed, before his imprisonment for seven years by the Derg, the Communist junta that toppled Emperor Selassie in 1974 and ruled through terror until 1991.

Today, Aberra worries about the deplorable conditions in Menz, where the “land is overpopulated and eroded” and people “cannot maintain themselves in farming alone.” “The Italian government is spending a lot on development here in Ethiopia, but they should do more to help Menz,” he told me. In the meantime, he’s enshrined the memory of the massacre in a poem he wrote in 1981, included in the memoir of Teshome Shenkut, which was edited by his nephew and translated into English in 2020. The verses are lamentations addressed to the cave but also, perhaps, to Ethiopia as a whole:

All the people of [the village] counted on you for a shield

How many people did you gulp down?

Tell us, Oh Cave, let’s hear it all

How many disappeared, how many did you devour?

*

For decades such literary evocations, along with oral testimonies, were the only accounts of the massacre, which seemed to vanish altogether from recorded history. The precise location of the cave was lost to the outside world. Then, in 2004, an Italian doctoral candidate at the University of Turin named Matteo Dominioni stumbled across a file in the Italian military archives that contained a one-page, handwritten note and an attached map. The unsigned document states that the “cave was poisoned with mustard gas” and that “in the morning about 800 were shot.” In the spring of 2006 Dominioni and an Ethiopian archaeology graduate student used the map to locate the cave with the assistance of villagers and priests. Stories about the discovery in La Repubblica and other papers soon followed, causing a sensation in Italy and spurring impassioned debates about the country’s legal culpability.

One evening that fall, just around dinnertime, Dominioni received a telephone call at his home. “Good evening, Mr. Dominioni,” the caller began. “We don’t know each other; I found your number on the Internet. My name is Giovanni Boaglio and I am the son of the person who employed the gas in the cave…I have always known about the existence of the cave. My father left a diary in which he talks about that massacre.”

Weeks later the graduate student read the diary, written by one Alessandro Boaglio, who had been a noncommissioned officer in the chemical platoon of the Grenadiers of Savoy and had served in Ethiopia from 1936 until his capture and internment by British forces in 1941. Among the notebook’s eleven chapters is one dedicated to the operation at Ametsegna Washa. In it, Boaglio describes abseiling in the darkness down the face of the rock above the cave, guiding the cable-bound mustard-gas canisters over the opening, acting, in effect, as the final executor of what he later concedes is an appalling plan. He wonders nervously if the Ethiopians inside will spot the hanging containers and cut them down, or shoot him in midair. Scurrying up the cliff, he avoids the blast of the detonation but not the noxious effects of the gas.

In the following days he witnesses the shootings of Ethiopian men and boys at the edge of the gorge, noting the laughter of the Italian troops as bodies fall to the ground. One wounded man is shot as he clutches at a shrub below the ledge, his face becoming a “mask of blood.” Boaglio also visits a makeshift encampment not far from his tent where women and children from the cave—visibly distressed, screaming, and dying—are kept under guard. “How to explain the tragedy of that scene? How to find adequate words capable of making such horror understood?” he writes. The cotton shammas of the women, normally scrupulously white, are tattered and sullied with dirt. Blood-clotted bandages cover gaping wounds. Everywhere on exposed skin, he sees blisters—“sinister and frightening boils, each one swollen with poison”—from the mustard gas bombs that he himself had emplaced. He watches one young woman “twirl the beads of a wretched rosary” as a “a deadly serum” drips down her chest.

The diary is a wrenching corollary to what Ethiopian witnesses had been saying all along. Excerpts of it appeared in Dominioni’s book The Collapse of the Empire: The Italians in Ethiopia, 1936-1941 (2008), based on his dissertation; two years later, an academic press published the journal in its entirety. Even so, the truth about what exactly happened at the cave became a magnet for criticism in Italy, much of it centered on whether or not the gas had lethal effects, especially on noncombatants.1

One of Italy’s leading speleologists, who is also a chemical engineer, traveled to Ametsegna Washa in 2008 and 2009 and concluded, based on a survey of the cavern’s interior and the dispersion properties of mustard gas—80 percent of it remained outside the cave, he asserted—that Dominioni’s tally of 800 to 1,500 Ethiopian deaths was vastly inflated. The entire incident, in his view, was a “battle” but not an “unjustified massacre,” the use of gas an “unfortunate decision” but one that needed to be viewed alongside the equally ruthless tactics of the Ethiopian insurgents. A study of Italy’s war on Ethiopia commissioned by the Italian army’s historical office, based entirely on Italian documents, similarly claimed to find no evidence of any deaths at all from mustard gas.

But Dominioni’s staunchest critics have been veterans and supporters of Italy’s elite corps of mountain infantry, the Alpini troops, distinguished by their plumed headgear and legendary elan. They are determined to protect the legacy of a much-beloved Alpini officer named Lieutenant Colonel Gennaro Sora, who was the on-scene military commander at Ametsegna Washa. The author of the “Prayer of the Alpino”—a nationalistic orison written to his mother in 1935 that has been recited at official Alpini functions, though not without controversy, given its reference to “our millennial Christian civilization”—Sora also enjoys wider popularity in Italy for attempting to rescue survivors of a doomed 1928 Italian airship expedition to the North Pole. Accordingly, his admirers argue that a man of such noble principles and heroic stature was absolved from culpability, either because of the exigencies of war or because he was following orders.

*

There’s a deeper subtext to these apologetics. For decades now, Italy has been afflicted by a sort of collective amnesia about its conduct during World War II—an officially sanctioned revisionism that has come to be known as Italiani brava gente, or “Italians, the decent people.” Evident in media whitewashing, omissions from school curricula, and the prevalence of skewed historiography, it has obstructed an honest, public reckoning with the nation’s colonial crimes. Only in 1996 did the Italian ministry of defense formally admit to the use of gas in Ethiopia.

The dissimulation endures to this day, especially as Italy is gripped by right-wing populism and xenophobia, embodied in the figure of the current prime minister, Giorgia Meloni. A self-admitted heir to Italy’s postwar neofascist movement, Meloni recently lambasted France’s colonial exploitation of Africa while failing to express any contrition for Italy’s predation of the continent. But this wave of fascist self-acquittal in Italy dates back to the tenure of the late Silvio Berlusconi, who famously quipped, “Mussolini never killed anyone.”

Shortly after the last Berlusconi premiership the mayor of the bucolic village of Affile, not far from Rome, used federal funds to begin construction on a monument for the purveyor of so much terror in Ethiopia and Libya, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, who was born near Affile and continues to be remembered fondly by its conservative citizens. An uproar ensued in 2012, in Italy and abroad, with diasporic Ethiopians launching an especially vocal petition campaign. While officials in Affile were convicted and sentenced, their case was ultimately annulled, and the shrine to Graziani still stands.

The controversy is hardly an isolated case. In recent years a number of political, artistic, and cultural initiatives have draws critical attention to fascist Italy’s colonial past, especially after the Black Lives Matter movement, which inspired protests and sit-ins in major Italian cities. But vestiges of that past are still visible in street names and monuments across the country. Travel today to Pisa, for example. Visit the iconic tower and then stroll north for about twenty minutes. Veer slightly to the east and you’re bound to cross the Via Generale Orlando Lorenzini, named for the general who was killed in battle in Eritrea by Allied forces in 1941.