Berenice Abbott was “the Tulloch-Turnbull girl with her coldblood Kodak” to James Joyce, “Berry” to her ex-roommate Djuna Barnes, a “spry old lady” to her friend Allen Ginsberg, and, to a reporter from Life magazine in 1938, just a “Springfield, Ohio girl.” Life was covering the progress of what was to become a classic book of photography: Changing New York, a representation of the growing city, on which Abbott was working with the literary critic Elizabeth McCausland.

McCausland, too, had moved from the Midwest to New York City, where she met Abbott in 1934. They were two grumbling communists in their mid-thirties, curmudgeons beyond their years. Within a year of meeting, they became “close friends” (Abbott’s preferred euphemism) and secured a Federal Art Project grant to work on the four-year effort that became Changing New York. From 1935 until McCausland’s death in 1965 they lived and worked in studio apartments across the hall from each other.

After living in New York for a brief period in her twenties, Abbott had spent much of the 1920s working as a portrait photographer in Europe. The idea for Changing New York came to her on a short visit to the US in the spring of 1929. In the years she’d been away, downtown and Midtown had erupted into Art Deco; construction on the Chrysler and Manhattan Company buildings was underway. “I felt that here was the thing I had been wanting to do all my life, photograph New York City,” she wrote. “So back to Paris, to wind up my affairs there. And back again to the United States with feverish excitement.”

She returned just in time to watch the Financial District crash and then grow: the Depression meant money for the arts had dried up, though the building boom continued. (Abbott applied for grants from the Guggenheim, the Museum of the City of New York, and the New-York Historical Society, with no success except for a single $50 check from a private donor.) She watched with her finger on the shutter, constantly trying, and usually failing, to secure funding for her time and equipment. She had intermittent success exhibiting her project-in-progress: “I wanted miles and miles of such pictures,” Lewis Mumford wrote in The New Yorker in 1934.

Historians have tended to attribute any leftist aspects of Abbott’s photography to McCausland, who had been active in support of Sacco and Vanzetti and various labor struggles throughout the 1920s, over a decade before she met Abbott. (Abbott’s FBI file, padded out by an informant from the downtown lesbian scene, has almost as much to do with McCausland’s political activities as her own.) But though Abbott was not as deep a political thinker as her partner, she too got involved in Marxist and antiracist politics. She was an important early member of the Workers Film and Photo League, a product of the Comintern; she dragged fellow artists to protests, donated to bail funds for political prisoners, and organized for civil rights. Former friends, some of whom conveyed their thoughts to the FBI, perceived her as a Communist, even though she never joined the Party; and Abbott did have a certain abstract passion for the cause, distancing herself from her friend Walker Evans for his upper-class aspirations and maintaining a sentimental attachment to Soviet propaganda art until her death, long after most American Communists had lost their taste for the stuff.

“The city has the romantic power of its dreadful reality,” she wrote in 1942. Though she conceded that some of the city’s “themes” were best left to literature, she was desperate to capture as many of them as she could. As she knew from the moment her ship pulled in and the new skyline came into view, her major theme would be the unprecedented scale of growth under new industry, new federal funds from the New Deal, and new philosophies of urban planning (Robert Moses was installed as the city’s parks commissioner in 1934). The Federal Art Project was created in 1935 as a relief measure for the nation’s creative class; with McCausland’s help on the application, Abbott was able to secure money, equipment, and a team. She became, in the scholar Sarah M. Miller’s words, “one of very few FAP photographers to have her project classified ‘creative.’”

*

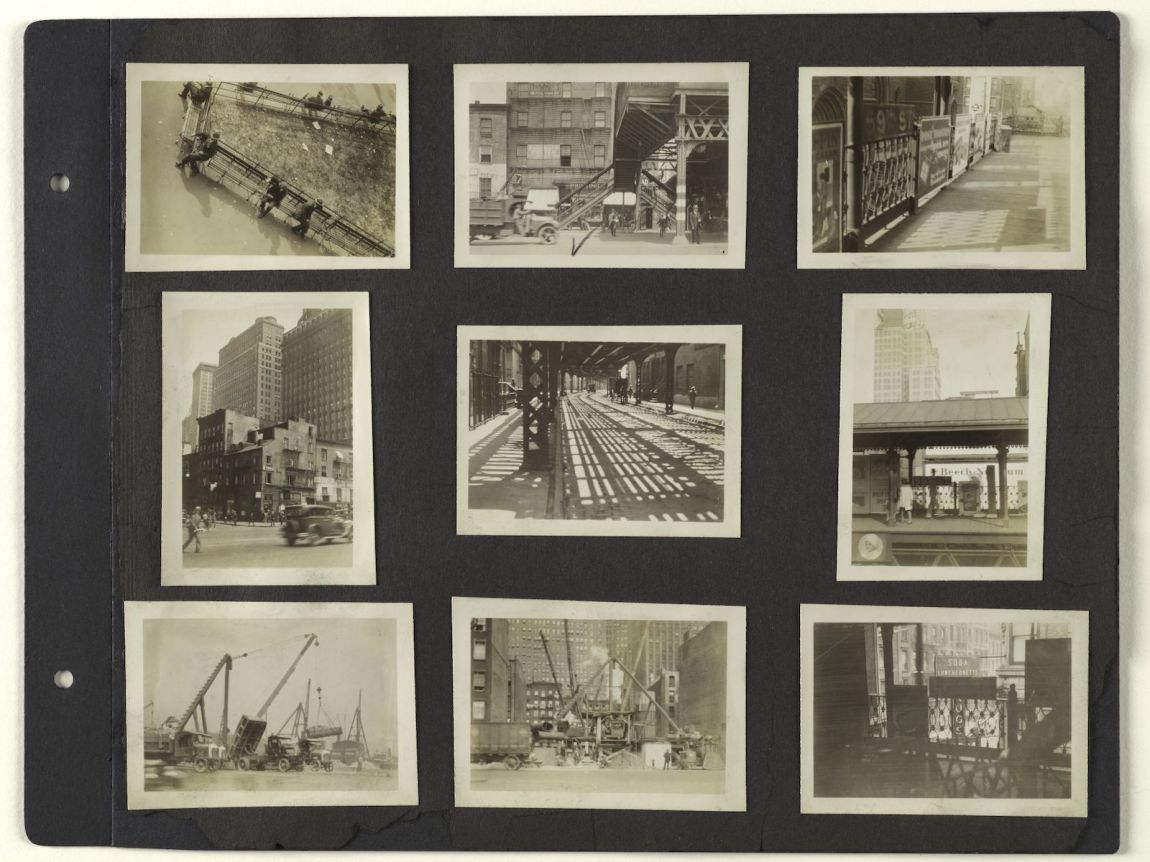

Berenice Abbott’s New York Album, 1929, organized by Mia Fineman, occupies a small exhibition room at the Met this summer. Fittingly for a photographer of accretion like Abbott, it is a collection of anthologies. The album of the exhibition’s title—her first attempt to, in her words, “fix for posterity the image of a modern city”—is on display alongside her portraits of modernist friends and her collection of her mentor Eugene Atget’s archive, which she bought after his death with a loan from a girlfriend and took to America. The exhibit also includes several of the photographs from Changing New York, which sold well, though Abbott never saw any profit.

Advertisement

The Changing New York published by Dutton, as the Met curators note, bore almost no resemblance to the project on which Abbott and McCausland had worked so hard. With the 1939 World’s Fair approaching, their editors, in conjunction with their funders in the Works Progress Administration, gutted their manuscript and rebuilt it into a tidy, circumspect guidebook for the impending hordes of tourists eager to see “the world of tomorrow,” cutting most of Abbott’s contributions and almost all of McCausland’s. “More than 10 percent of the photographs,” in Miller’s words, “were excised and replaced,” including, at the last minute, a picture of segregated Harlem. The remaining images were reorganized in geographical order, so that someone might keep the book in their hand as they wandered around the city.

McCausland and Abbott had high pedagogic aspirations. They believed it was their duty to educate the masses on how to see the new city: the photographer should be “trained in history and architecture,” Abbott wrote, with “an understanding of the interplay of forces in the world today, how history affects his daily life and how it alters the face of his city.” Like many in their leftist milieu, they were admirers of Mumford’s architectural history Sticks and Stones (1924), and their FAP proposal borrowed his description of the city’s essential framework: they separated the sections on New York’s “material aspect” (the architecture), its “means of life” (the transit systems), and its “people and how they live.” If a reader took these photographs as mere documentary representation—a tourist’s guide to the city—they would miss the photographer’s artistry and misunderstand the beauty of the city’s growth.

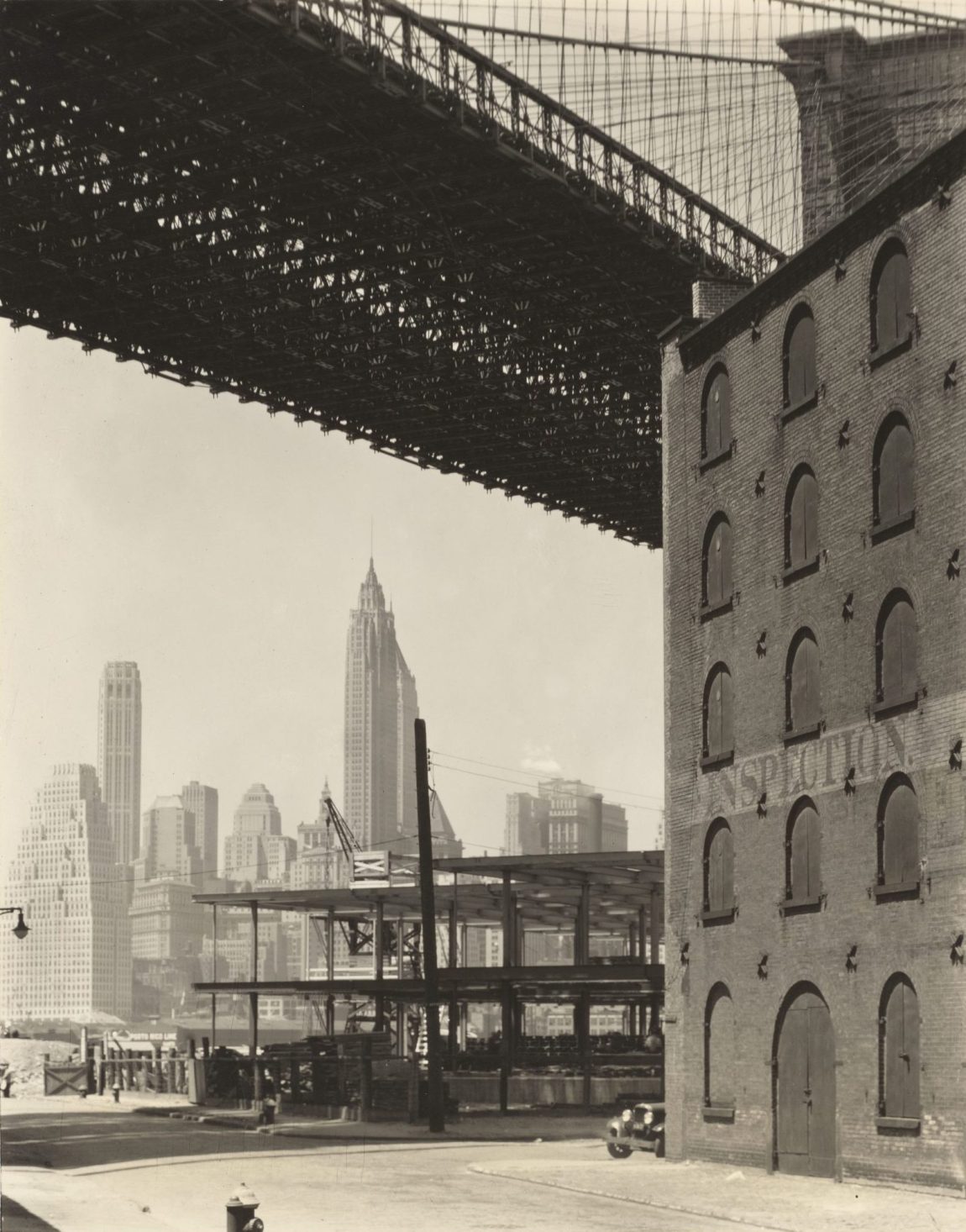

The original manuscript—recreated by Miller and published in 2020 by MIT Press and the Image Centre in Toronto—opens with a view of Brooklyn Bridge from what is now DUMBO. Two curt sentences accompany the photograph in the edited, published text, where it appears late in the book as one of relatively few outerborough images:

Brooklyn Bridge is the technological ancestor of all the great steel cable suspension bridges which connect Manhattan Island with the world. The Roeblings’ success in devising a steel cable strong enough to support the strain of its mighty span opened the way for the Williamsburg, Manhattan and George Washington Bridge.

The published caption gives no suggestion of anything to interest the eye in the photo, let alone the bridge itself. Here, in contrast, is McCausland’s original entry:

The taut cables of the first bridge to link Manhattan with Brooklyn visibly soar above the brick warehouse. Every molecule of steel in the fine-woven strands and in the interlacing girders and beams contribute to the perfect equilibrium of suspension. At the same time, this tension (invisible to the eye, which scientists have been able to photograph at speeds of one-millionth of a second) is a living element in the picture. Between the power of steel and the pull of gravitation, the photograph achieves its own equilibrium, powerful and dynamic.

Abbott’s camera is capable of both might and precision; elsewhere, McCausland describes it almost as a creature in its own right, with its own particular urges. (The light on Exchange Place, she wrote, was insufficient for “the optical and physical needs of the camera,” whose “eye cannot hope, therefore, to register minutiae of detail. It can only look upward to the sky for the light which is its indispensable instrument.”) At the same time, it is drawn to its mechanical kin, especially metal in all its forms: trains, trolleys, water tanks, wrought-iron fences, fire escapes, bridges.

The Met includes many of Abbott’s photographs of skyscrapers—mostly from the ground up, taken from what she liked to call the “canyon” between them—alongside a few by her peers, to contrast her conversational style with the abstract modernism of Paul Grotz and the daredevilry of Margaret Bourke-White. In Bourke-White’s picture of the Chrysler, taken from outside its top floors, the top of the building stands at voluptuous remove, like a portrait of a Gilded Age heiress; the Grotz photographs are beautiful, rigid monuments to regularity and dichotomy, in thrall to the Manhattan grid. Abbott and McCausland were not interested in drawing such a stark contrast between the past and the present. They were, Abbott wrote, after a “synthesis which shows the skyscraper in relation to the less colossal edifices which preceded it.”

Advertisement

The marvels of the new age had been imposed on the city from above. “There is no way of photographing the gigantic monuments of Manhattan’s financial district except by extreme distortion,” McCausland wrote. (No need to say, as a more doctrinaire duo might have, that the financial world in New York in the 1930s was the cause of many extreme distortions.) Abbott and McCausland allied themselves with the engineers; they were partisans of the sensuality of infrastructure, the “dynamic equilibrium” among steel cables, parts of a photograph, and people in a street that made those things whole. Dutton and the WPA had hoped they would produce a celebration of New York’s great leap forward, but Abbott and McCausland didn’t believe in such simple movement. “The changing in Changing New York,” Miller writes, “would be not a linear progression in which old gives way to new, but a scrutiny of the interdependence of destruction and creation, neglect and innovation, visibility and disappearance.”

Every move into the future summoned its own history; each singular technological achievement depended on the labor of thousands. “No great engineering construction is completed without a technical organization as complex as an esthetic synthesis,” McCausland wrote.

To this miracle, the city-dweller is commonly blind. He passes over bridges or through tunnels, walks by skyscrapers, uses a myriad facilities, but never sees them. To him the artist presents the fact of daily life, the apparatus by which 7,000,000 people live, but with a new meaning. Every rivet, bolt, nut, screw, beam, girder of Manhattan Bridge, as one looks up at it, comes to life as the portrait of integrated technics by which civilization survives.

In a photograph from the New York Album, a sign shaped like a hand instructs pedestrians to “look up.” It’s an advertisement for a luggage shop, but none of the people in the photograph are looking up, and the camera doesn’t bother to capture the suitcases the hand is pointing to. Still, the imperative to “look up” grasps the viewer tight. As the city rocketed upward, new connections were made in the sky: bridges and clotheslines strung up, train stations and highways lofted. Buildings and the people in them competed for a shot at the sun. Look up, Abbott says: it’s where the past is recorded, where the future is promised, and it’s the best view of the present.