Every spring, when students come to my office and ask for advice about life after graduation, I tell them the same thing: don’t become a graduate student, instead try to become a bank, because then the government will care about you. I did not expect the first six months of 2023 to demonstrate the point with such precision and cruelty.

There are three immediate reactions to the Supreme Court’s decision in Biden v. Nebraska to block student loan forgiveness. First, of course it is a hypocrisy impressive even by the standards of the time. Compared to Clarence Thomas’s gifts from the richest 1 percent of Nazi memorabilia enthusiasts, the sudden payment of Brett Kavanaugh’s extravagant credit card debts, or Samuel Alito’s propinquity to hedge fund billionaires, apparently the decision to take out loans to get an education is unforgivable. As so often, here the court is symptomatic of a wider elite trend. The database of the Paycheck Protection Program is a rich seam of forgiveness, including, variously, $960,000 to the quarterback Tom Brady’s sports performance and nutrition company and $447,000 to OceanGate, the now-famous operators of Titanic submersible tours. Don’t become a student, become a millionaire quarterback’s wellness company, because then the government will forgive your loans.

Second, of course the decision undermines the legitimacy of the court. But that ship has surely sailed, with no obvious consequences. Short of the Biden administration declaring that Marbury v. Madison is itself illegitimate because judicial review does not appear in the Constitution, it is unclear how the power of an illegitimate Court will be less than that of a legitimate one. The administration is already announcing that it will explore other solutions, and perhaps it will find one. Doubtless there are other emergency powers available to the executive, or baroque means-tested stratagems that will appeal to Congress. But as Keynes might have said to student borrowers, the court can stay illegitimate longer than you can stay solvent.

And third, of course the decision is fiscally unnecessary and economically harmful. The 40 million Americans whose payments will resume in October will not spend that money on goods and services; they will pay it to the Department of Education, which does not need to turn a profit, and which will not itself spend that money buying goods and services. The previous assault on student borrowers, shouted in the middle of the debt ceiling theater, also appeared in the guise of fiscal responsibility. A solid bloc of Republicans, plus Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and Jon Tester, passed a resolution to use congressional rules to overturn what the representative Virginia Foxx called “the Biden Administration’s student loan scam” on the grounds that it “could end up costing taxpayers $1 trillion.” Biden vetoed it immediately. The eventual deal to raise the debt ceiling included a provision that the pause on student loan repayment that began under Trump in 2020 and was extended by Biden would end, and the administration would be prevented from extending it again without congressional approval.

There are allocative reasons not to take claims like Foxx’s seriously (we can afford that Pentagon budget, after all) and technical reasons (the US government borrows in its own currency, which it produces at will) and Keynesian reasons (erasing debt from the Department of Education’s balance sheet harms no private borrower and stimulates spending). Claims to fiscal responsibility are so clearly a matter of transparent partisan conflict that the only surprise is how often Democrats take them seriously.

The Court’s decision helpfully clarifies that the loan forgiveness program threatened the state of Missouri with “concrete and imminent harm to a legally protected interest, like property or money,” because it “would cost MOHELA, a nonprofit government corporation created by Missouri to participate in the student loan market, an estimated $44 million a year in fees.” That’s the rationale: not a moral claim about the necessity of repaying debt, not a fiscal claim about the federal budget, not a legal claim about the inviolability of contracts. To forgive student loans would reduce MOHELA’s fees, and that would be unforgivable. Don’t become a student, become a nonprofit corporation participating in the loan market, because then the government will protect you from concrete and imminent harm.

*

Beyond these three reactions, what is more striking about the court’s decision is the problem of forgiveness. The political history of that problem is in its infancy. Analyses of adjacent subjects have begun to accumulate over the past two decades, as spectacular mass crimes have provoked thinking about amnesty and clemency, sovereign immunity and the International Criminal Court. All of those subjects are close to forgiveness but distinct from it.

Modern thinking on forgiveness might begin with the 1726 sermons of the Anglican bishop Joseph Butler. He warned against malice and revenge, both as the anger of individuals and as a social principle. But he was not altogether opposed to resentment, nor did he think it irreconcilable with goodwill and self-love. For him forgiveness was a kind of righteous resentment, because “the passion of resentment was placed in man, upon supposition of, and as a prevention or remedy to, irregularity and disorder.”

Advertisement

Butler found it perfectly natural to hate and resent the perpetrators of wrongs and injuries, and maintained that even a moral society was consistent with some forms of public retribution, because “a general and more enlarged obligation necessarily destroys a particular and more confined one of the same kind, inconsistent with it.” In contrast to the contemporary therapeutic emphasis on letting go, for Butler forgiveness and resentment could go hand in hand.

Who has the right to ask forgiveness, or to grant it? The right to forgive has adhered at least as often to power as it has to the wronged party. Ten years before Butler’s sermons, the Regent of France employed a different version of debt settlement, the chambre de justice, a kind of ritual prosecution of all of the Crown’s creditors after the War of the Spanish Succession, on the assumption that they must have done something illicit or immoral at some point, as well as to satisfy public demands for justice and accountability. It was the lenders, not the borrower, who had to ask to be forgiven. The fines and banishments the chambre issued were forms of structured default on the sovereign debt, which was still the personal debt of the monarch, not the perpetual debt of the government. This is one example of a general point: the dispensation of forgiveness and clemency has been, and remains, a constitutive feature of sovereignty.

How should contradictory claims to forgiveness and harm be adjudicated? In the aftermath of the 1720 financial crisis, many writers argued over whether it was moral to uphold the rights of creditors over debtors in all cases, or whether creditors had only second-order claims to things they did not themselves produce. The moral stain of usury still clung to lenders, especially those who seemed not to follow the local strictures of tradition, custom, and fairness that governed economic life. (That the king was a debtor strengthened this argument.) The question remained unsettled and subject to emergency revision. Many of the great conflicts of the French Revolution hinged exactly on who owed what to whom, and who could be forgiven, or called to account. Indemnities and sovereign defaults repeated similar problems, from the Napoleonic reparations of 1817–1819 through German reparations after World War I. The power to either forgive or insist on the full repayment of debt could have been distributed very differently.

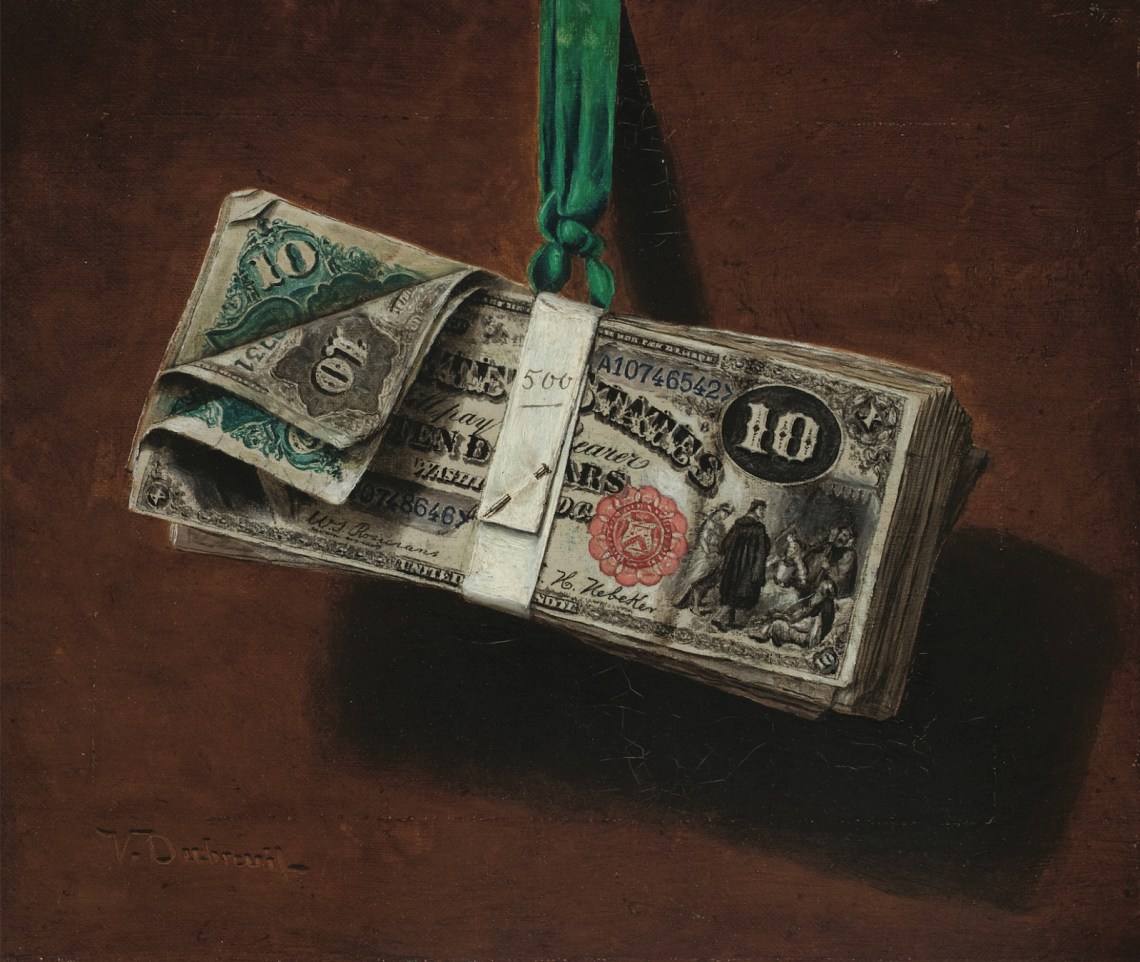

It seems clear that in the US today debt is a disciplinary tool. Students, homeowners, medical patients, and the governments of poor countries are subject to the discipline of debt; heavily leveraged investment banks, Supreme Court justices, and the Pentagon are not. Workers who have to make student loan payments are unlikely to make demands of their bosses, especially since student loans are no longer dischargeable in bankruptcy, thanks to a 2005 law championed by Joe Biden during an election cycle in which he received $500,000 in Senate campaign contributions from the financial sector.

American society is constituted by inequalities, and one of them resides in the political economy of forgiveness. The specific character of that economy probably dates to another illegitimate Supreme Court decision, Bush v. Gore (2000), a rupture in the distribution of justice and accountability that has never been repaired. The subsequent promoters of the Iraq War are today not only forgiven but feted, and the bloody ledgers of the torturers have apparently left no outstanding balance. The erosion of civil liberties at home and the extrajudicial killings abroad are bipartisan enthusiasms that no longer register as things to forgive. The banking leviathans of 2008, groaning under hundreds of billions of dollars in debt, represent a strange permutation of this phenomenon. Many of them repaid their debts to the Treasury for its TARP funds, and some of the executives returned the bonuses they received for running their ships aground. Did they owe a debt to the 8.8 million people who lost their jobs, or the 6 million who lost their homes? On the contrary, those borrowers were expected to pay their debts in full.

The crimes of the rich are more readily forgiven than the debts of the poor. The result is a corrosion of political and civic life. The public voice today is a steady choir of demands for redress, accountability, punishment, and justice, but those demands are mostly expressed through the legal system, which is one of the most powerful anti-majoritarian institutions in American governance. In the contemporary class war, the refusal to forgive is the prerogative of the winners, leaving the far more numerous unforgiven to covet the implacable resentment of the elite.

Advertisement