In response to:

The Long War on Black Studies, June 17, 2023

To the Editors:

Journalists and scholars regularly struggle to write accurately about racial controversies, and now your venerable review has conveyed two accounts—by Adam Hochschild and Robin D.G. Kelley, respectively—that distort an important component of Florida’s Stop W.O.K.E. Act.

In launching his trenchant and illuminating critique of recent state laws that target Critical Race Theory [“The Long War on Black Studies,” NYR, June 17], Professor Kelley offers a widespread but manifestly flawed interpretation of the 2022 Florida statute. Kelley correctly notes that it prohibits attempts to “indoctrinate or persuade students to a particular point of view inconsistent…with state academic standards.” Kelley errs significantly, however, by adding that the law “prohibits teaching anything that might cause ‘guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress.’” Kelley then proffers the alarmist conclusion that “introducing and teaching race, gender, sexuality, and anything remotely resembling critical race theory” is now “strictly prohibited.”

Regarding the above-mentioned types of distress, the relevant clause in no way precludes content that “might cause” any of them. It merely prohibits teaching that a student “must feel” distress (because of actions “in which the individual played no part, committed in the past by other members of the same race, color, sex or national origin”). It says nothing, in other words, about how students might react to learning about slavery, lynching, rape, or other horrors. As I elaborated in “Discomfort Is Still Legal” (Inside Higher Ed), similar errors have been proliferating in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and comparable venues. The Times eventually corrected three articles from 2021–22, but two subsequent articles repeat the original mischaracterization (see here and here). To his credit, Kelley soundly interprets the plank about “distress” later in his essay, when tracing the sprawl of anti-CRT legislation to President Trump’s Executive Order 13950, which had restricted the teaching of “divisive concepts.”

Kelley’s online essay links to an Adam Hochschild article [“History Bright and Dark,” NYR, May 23] that appeared also in your print edition. Hochschild’s paraphrase of the Florida statute—that it “forbids instruction that could make someone feel guilty or ashamed” about the past actions—relays the common error.

I concur with Kelley’s complaint that SB 266, a more recent Florida bill about public higher education, constitutes a “flagrant attack on academic freedom and faculty governance.” Here too, though, he adds distortion. According to Kelley, for example, the new law forbids teaching that “systemic racism, sexism, oppression, or privilege” are “inherent” in US institutions and were created to maintain “inequities.” That restriction, however, applies only to “[g]eneral education core courses” (556-61). And the law’s prohibition on “advocating” DEI or “participating in political or social activism” does not constrain “faculty or staff” (Kelley’s phrase) generally. It applies to university institutions that are spending public funds (309-16), and the statute permits “access programs” that support diverse students, including first-generation, “nontraditional,” “low-income” families, and Pell Grant recipients (338-42).

If we cannot rely on scholarly venues and top-tier newspapers to inform us meticulously about controversial political, legal, and cultural developments, what institutions will fill the breach?

Peter Minowitz

Professor of Political Science

Santa Clara University

Santa Clara, California

Robin D.G. Kelley replies:

I will concede the semantic distinction between teaching subjects that “might cause” distress and teaching that students “must feel” distress, as the language of Florida’s Stop W.O.K.E. Act states, but such quibbling completely misses the point of the law—to intimidate educators. The climate of fear created by these laws makes actual enforcement unnecessary. In Miami, a seventh-grade civics teacher was warned against bringing up the lynching of Emmett Till because, according to the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, “people say you’re not supposed to talk about that because it will make children uncomfortable.”

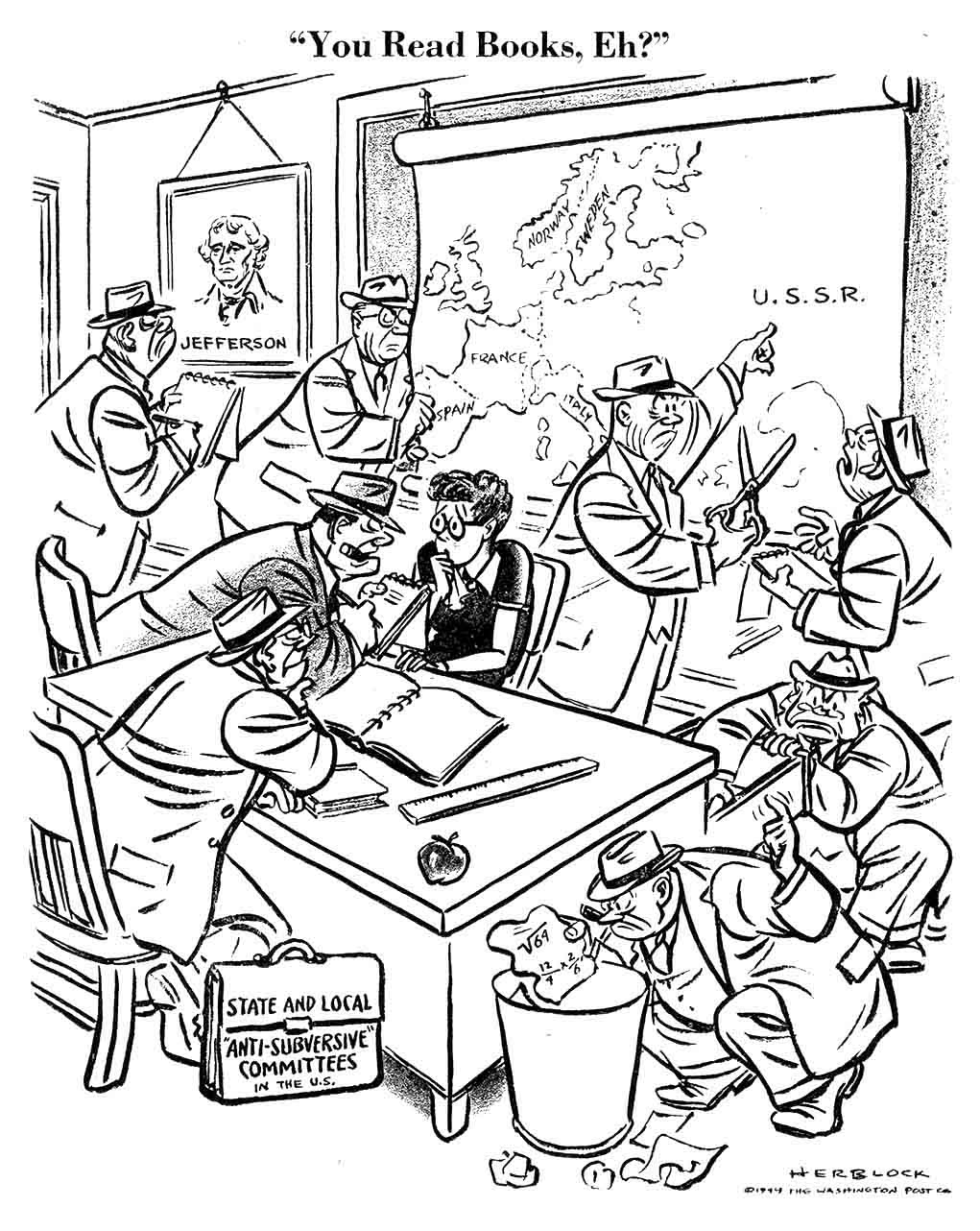

We know from a flood of articles and social media that Florida teachers are afraid of running afoul of the law. Many feel as if they have no choice but to self-censor, purge their courses of “anything that might cause ‘guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress,’” or quit their jobs. The effect is analogous to the wave of extreme state anticommunist laws passed in the early 1950s, when Michigan imposed a life sentence for anyone “writing or speaking subversive words” and in Tennessee “unlawful advocacy” mandated the death penalty.1 No one was ever convicted because the point of such draconian legislation was to create fear.

Besides, as I pointed out in my essay, no one working in critical race studies teaches students that they “must feel” guilt or shame on account of their race. It is not only absurd but contradicts the very framework of anti-racist education. A law prohibiting a virtually nonexistent practice is intended to scare teachers.

On the second point, Professor Minowitz is mistaken. First, I clearly refer to SB 266 as an “attack on Florida’s state university system,” i.e., “university institutions that are spending public funds.” Nowhere do I claim that SB 266 applies to all of Florida’s higher education. Second, he seems to have overlooked the law’s first reference to bans on teaching that systemic racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression are inherent in US institutions. The section to which I am referring grants the Board of Governors power to review “the mission of each constituent university” and “existing academic programs” and issue directives

Advertisement

regarding its programs for any curriculum that violates s. 1000.05 or that is based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities (121-131).

The language here is not limited to general education classes, and thus opens the possibility of a blanket ban. Indeed, the law’s vague language has been the source of confusion and frustration for educators and administrators, many of whom have taken the extraordinary step of altering curricula that might be in compliance.

Finally, the “access programs” mentioned in SB 266 only apply to military veterans, nontraditional, first-generation, and low-income students, transfer students from community colleges, Pell Grant recipients, and students with disabilities (338-342). Excluded are programs such as diversity and cultural competency training for faculty and staff, support services to address the needs of students of color and gender nonconforming students, and strategies to ensure increased representation in personnel, to name a few. And as Professor Minowitz surely knows, some of the access programs the law allows cannot be eliminated without violating federal laws, and there is nothing in the legislation that requires the state to fund them. In the end, my chief point stands: these attacks on Black Studies, in particular, and education, in general, are political and indefensible.