1.

When my sister and I were kids we used to listen for the resonant horn of New Jersey Transit and run out to meet my dad coming up the block in the twilight. We always lived near a train station so he could commute to a postproduction studio in the city. Sometimes he’d have movies in his briefcase, ones we couldn’t get at Blockbuster: subtitled Studio Ghibli VHS tapes on loan from a coworker, and the Streamline dubs from Kinokuniya, the Japanese bookstore in midtown.

For my sixth Halloween, my mom sewed me a dark purple dress and put my short hair up in a red Junie B. Jones–style bow, and I savored our reenactment of the scene in Kiki’s Delivery Service in which Kiki stands in front of a mirror as her mother fixes her hem. She is about to leave home to complete a rite of passage for teenaged witches: living on her own in another town for a year. She’s itching to go, but as she looks at her reflection her face falls. “Oh mom,” she says, “I look really… dumb.” In another reenactment, I would fling myself off a parapet at the base of our lawn. Kiki, having established an air-delivery business in the big city, suddenly loses her ability to fly. She runs downhill on her broom, struggling to get airborne, and lands in a ditch. “I’m still in training to become a witch,” she says to her landlady, distraught. “If I lose my magic that means I’ve lost absolutely everything.”

The 1989 animated film is based on a lighthearted novel for adolescent girls, each chapter a delivery gone awry. But Kiki’s ennui—the faceplant on the bed, the dead-eyed stare—plunges it into emotional territory that I would only become acquainted with as I grew older. Everyone wants Kiki to succeed, but she deflects their admiration and constantly sells herself short. The film’s only antagonists are the local joyriding teens, of whom she has a social terror, and an enormous dirigible that seems to mock her ability; that is, the conflict is almost entirely psychological. “Maybe you’re working too hard,” an older friend, a painter, counsels:

Ursula: When you fly, you rely on what’s inside of you, don’t you?

Kiki: We fly with our spirit.

Ursula: Trusting your spirit, yes! That’s exactly what I mean. That same spirit is what makes me paint, and your friend bake. But we each need to find our own inspiration, Kiki. It’s not easy.

Hayao Miyazaki modeled Kiki’s character on the young women who had moved to Tokyo to become manga artists and instead found themselves painting acetate on an assembly line at Ghibli. Their animations were inscribed as colorful maps on my brain when I was very young, but for a long time I couldn’t say what they were truly about, although dialectics like Ursula and Kiki’s appear in almost every one of Miyazaki’s films. The director sticks to a deliberately vague line, one that could be applied to the most anodyne Disney venture, that all his films are about “how to live.” Few scholars or critics have done the work to penetrate this author’s statement. “What’s it about?” asked Nigel Andrews of Spirited Away. “Simple answer: Everything.” Ligaya Mishan writes that Miyazaki’s films seem to “thwart the Western mind.”

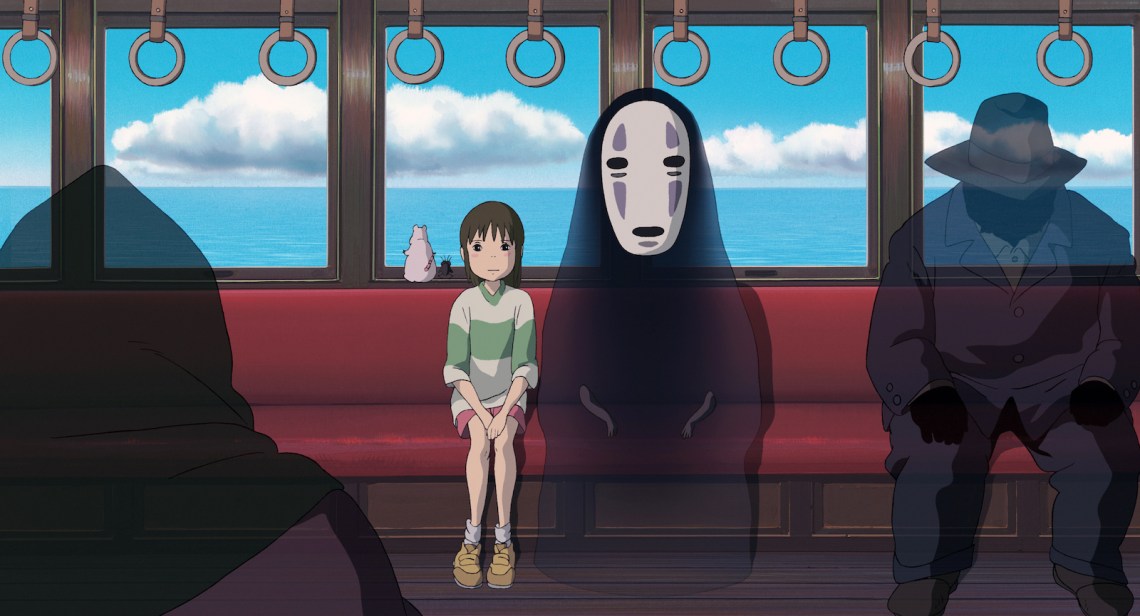

Yet his greatest theme, a certain alienation he diagnosed in Japanese society, affects Americans as well. At seven, the strange melancholy of the train scene in Spirited Away revealed something inarticulable to me about my father’s bifurcated life. Ten-year-old Chihiro has taken a grueling job in a bathhouse for spirits, and with the help of friends manages to escape her workplace for the first time, taking a commuter train to the end of the line. For Miyazaki that ride traversed a metaphysical boundary. The scene is uncanny not just because the train is full of ghosts but because Chihiro is a child, and the other passengers are adults. She watches out the window as they disembark at a local station and sees the shadow of another girl standing on the platform—the distance, and difference, between them finally signaling how Chihiro has been changed by her entry into the adult economy.

Miyazaki’s final feature, in production since 2016 and premiering in Japan tomorrow, takes the title of the 1937 novel How Do You Live? by Genzaburo Yoshino. The book is structured as a dialogue between a middle-schooler and his uncle that ranges from physics to philosophy to political economy, always applied to the child Copper’s everyday thoughts and experiences. One of its central lessons follows from Copper’s visit to the home of Uragawa, his bullied classmate who falls asleep at school. He discovers that Uragawa has been absent because he has been helping in the family’s fried tofu shop. He watches, rapt, as Uragawa expertly handles the frying tofu with long chopsticks and dries it on a wire rack. Later, when Copper’s uncle asks what he thinks is the greatest difference between him and his classmate, he answers that Uragawa’s family is poor.

Advertisement

The essential distinction is, rather, that Uragawa is a producer and Copper is a consumer. “Try not to overlook this point,” his uncle tells him:

Between the people who produce things over and above what they consume, and send them out into the world, and the people who don’t produce anything and who do nothing but consume, which are the great human beings? Which are the important human beings?… If nobody made anything, there would be no tastes, no pleasures—consumption would be impossible. The work of making things itself makes it possible for people to be truly human.1

Yoshino was imprisoned for his socialist politics during the interwar rise of authoritarianism in Japan. Upon his release he found work at an academic publisher, where he was tasked with writing a textbook on ethics for children. In the guise of a novel, How Do You Live? escaped the notice of the Tokkō, the thought police, for nearly a decade before it was banned and censored.

“Work—always present somehow, always close to our thinking lives—is itself near enough to us that theorizing can miss the grainy, interesting, unexpected bits and take us only part way round to the truth,” the novelist Richard Ford has written. But to take it up in art, he estimated, is nothing less than “the ignition mechanism for illuminating and identifying something important and up-to-now unknown about humankind.”2 Miyazaki’s mission to create meaningful and uplifting entertainment for kids, radical in itself, has undoubtedly partly obscured his core preoccupation as a filmmaker: it’s by looking through the eyes of children, who don’t yet know the meaning of work, that the great problem of adult life can be seen and approached.

2.

A boy sits alone at a desk working a piece of wood under the light of a lamp. Shavings curl away from his chisel, which he holds between his thumb and crooked index finger, his other fingers steadied against the wood, which his left hand rotates gently but firmly against the knife. He lifts the piece, so he can see straight down its length, and examines its lines.

A girl prepares an oven for a casserole. She carries heavy logs from a shed, builds the kindling, lights the edge of the newspaper with a match and then tosses the match in, and stokes the fire until it has burned down to embers and the bricks are hot. Her sleeves are fastened back with clothespins. Sweat drips from her brow.

A hallmark of the films of Studio Ghibli is their realism. Their twinned pleasures are the imaginative visual leaps and analogies that animation makes possible and the carefully observed details from life that, like precise prose, stir recognition. The development of the Ghibli style—of any animation style—was a matter of engineering as much as aesthetics. Early innovations by Miyazaki and his peers included figuring out how to naturalistically capture the act of running over a fixed frame rate and how to break the constraints of horizontal movement in order to depict action that moves from background to foreground. Disney and Pixar would study Japanese animation, and increasingly Ghibli’s films, for solutions to technical hurdles.

But the approach to realism Miyazaki shared with Isao Takahata, his collaborator, colleague, rival, and peer throughout his filmmaking career, extended beyond visual fidelity. “Human beings live in the midst of all sorts of other things, including a certain relationship to production,” Miyazaki said in an interview in 1997, “so it isn’t right to make films that only depict the feelings and thoughts and human relations of the main characters. What was their source of livelihood?”3 While his politics have shifted over the decades, his plots, his characters, their loves and dreams and conflicts, have all turned on a Marxist view that the human spirit is expressed in work.

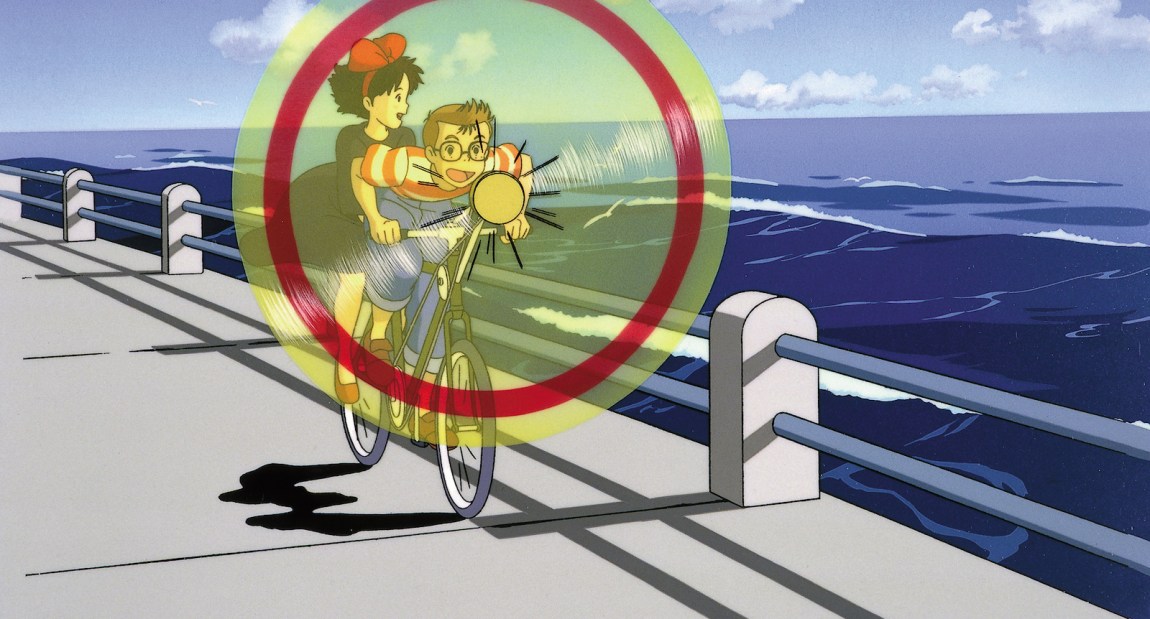

Miyazaki’s boys are budding engineers who strive to achieve what the girls they admire seem to do effortlessly. Magic doesn’t contradict mechanics, but complements it. Kiki fends off the attentions of Tombo, a boy trying to turn his bicycle into an airplane in his garage. When they take it on a test ride and spin out of control, they’re briefly airborne. “Was it your magic that made us stay up?” he asks after they crash. “I don’t know,” says Kiki, “anything’s possible.”

Advertisement

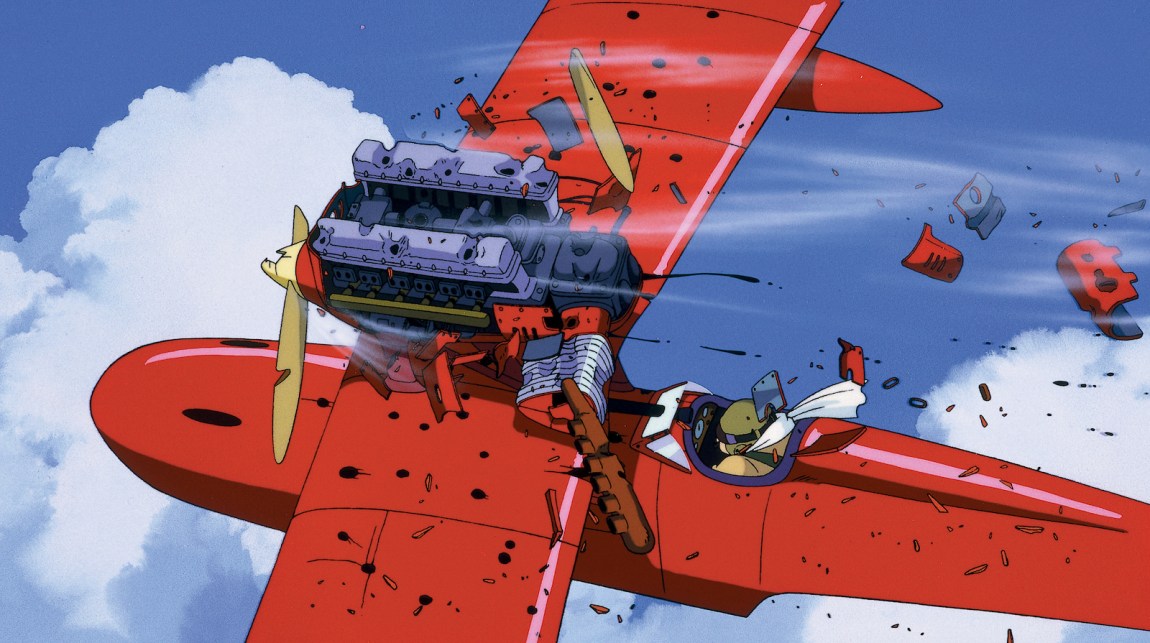

They could be avatars of the animator: the trained hand that is useless without inspiration, the intrinsic talent that can only be consummated with discipline. In Porco Rosso, the plucky young airplane designer Fio attaches herself like a barnacle to Porco, the finest pilot in the Adriatic turned misanthropic bounty hunter. His trauma during World War I—grief and shame at being the only surviving member of his squadron—has left him disfigured with the face of a pig. At first he’s reluctant to let a teenage girl rebuild his red seaplane, but she convinces him to give her a chance:

Fio: Tell me what you think it takes to make a pilot great. Experience?

Porco: No, it’s intuition.

Fio: I just knew you weren’t going to say experience.

Later he’ll fight for her in the plane she’s redesigned, a plane that only he can fly. Miyazaki was entranced with the idea that, during the days of wooden aircraft, the touch of the craftsman could influence a plane’s performance just as the sound of a violin is a duet between its luthier and the musician. It’s not Gina, Porco’s old flame, whose love redeems him, but Fio’s kiss (it’s implied) that breaks his curse and turns him back into a man. In film after film romance is subject to annihilation by illness, war, and time, but lives can always be repaired by labor.

Even Ghibli’s take on a shojo romance, Whisper of the Heart, uses the charged theater of the middle school crush to tell a story of creative genesis. In the original manga by Aoi Hiiragi, a girl, Shizuku, pursues a mysterious boy whose name she keeps finding on library checkout cards. He turns out to be a painter, a kindred spirit who inspires her to start writing. Ghibli’s adaptation, directed by Yoshifumi Kondo in close collaboration with Miyazaki, relies on a reimagination of Shizuku’s crush as an aspiring violinmaker. In the film, Seiji Amasawa is an almost tragically serious figure who, like the American Fio, intends to forgo high school to apprentice in a workshop in Italy. In the production notes Miyazaki asks, “When our young heroine encounters such a boy, what happens?”

Confronting Seiji’s discipline and clarity of purpose, Shizuku decides she’s unworthy of him until she’s produced a novel, a project that threatens to derail her high school entrance exams and, by extension, her life. There is an austere dignity to the way she imagines Seiji at work (she finds an engraving in a library book of a prisoner making a violin in a cell), but her own creative practice involves shirking chores and skipping meals for a drawer of candy, sleeping in her clothes and on the floor. Her parents, staging an intervention over her failing grades, warn her: “It’s never easy when you do things differently from everyone else. If things go wrong, you’ll have only yourself to blame.”

What they don’t know is that their daughter is not alone. It was Miyazaki’s idea to end Whisper of the Heart with an improbable marriage proposal, but the shape it takes—“I promise I’ll be a professional violinmaker, and you’ll be a professional writer!”—is a commitment as much to their talents as to each other. With their deemphasis on sex, the relationships in these films are animated by “a third partner: the work,” to borrow words from the philosopher Gillian Rose. “The work equalizes the emotions, and enables the two submerged to surface in series of unpredictable configurations.”4

Ursula, the painter in Kiki’s Delivery Service, suffers creative blocks, too, when she can only make “copies of paintings I’d seen somewhere—and not very good copies, either.” She has ulterior reasons for inviting Kiki to visit: “Today when I saw you I thought, I want to paint! You’ve got such a great face!” Kiki is uncomfortable as a model and mortified as a muse, but Ursula can’t apologize for seizing inspiration when it strikes. “It’s better than you scrubbing my floors,” she says. This is the wisdom that restores Kiki’s mojo: how to be someone else’s inspiration, how to turn it back into your own.

3.

Hayao Miyazaki was born in 1941 in Tokyo. He grew up sickly and described his childhood insecurity as a “gap between his inner self and the world,” one that could only be filled by drawing. The family business was an airplane parts manufacturer for the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Japan’s main combat model during World War II. The Miyazakis lived comfortably and survived the war intact, though his mother spent the following decade suffering from spinal tuberculosis and hospitalized for long periods.

As a teenager, Hayao’s ambition to be a manga artist outstripped his modest talent. When he saw that his early attempts looked like imitations of Osamu Tezuka’s comics, he burned them. At university he studied economics and political economy, majoring in Japanese industrial theory. On Saturdays throughout his college years he would practice drawing at the studio of his middle school art teacher, a painter. The drawing went poorly but the two would drink and talk about “politics, life, all sorts of things.” In 1963, after a discouraging attempt at shopping his manga manuscripts to publishers, he was recruited by Toei Doga, Japan’s premier animation studio, in Tokyo.

Miyazaki had decided to become an animator after seeing Toei’s first feature, Hakujaden (Tale of the White Serpent), released in 1958 when he was seventeen. Lushly yet precisely animated entirely in color, it seemed to inaugurate the studio as a peer to Disney. The story was based on a Chinese folktale, a boy who gives up his pet snake only for her to return to him years later as a beautiful goddess. Miyazaki’s obsession with Hakujaden took the form of a fixation on Bai-Niang, the snake goddess, who became a “surrogate girlfriend” to him:

I fell in love with the heroine of this animated film. I was moved to the depths of my soul…. I was no longer able to deny the fact that there was another me—a me that yearned desperately to affirm the world rather than negate it.

After many viewings, and the disillusionment that came with actually working in Toei’s sweatshop, he came to find the film overly sentimental and melodramatic. By the time Miyazaki was hired, the animation staff had unionized. As Jonathan Clements notes in his history of anime, animators who had worked on Hakujaden had made the equivalent of $500 a month, and many suffered what became known as “anime syndrome,” the cumulative effects of stress, poor diet, and lack of sleep that sometimes led them to collapse in the studio.5 The union won higher base pay and supper during overtime.

Solidarity in the union was channeled into the filmmaking. The members read leftist texts and watched reels from Disney and Moscow’s Soyuzmultfilm. Miyazaki was drawn in by the union’s magnetic vice president, Isao Takahata, six years his senior, and served as its general secretary in 1964. Takahata was a staunch Marxist and remained so all his life, while Miyazaki flirted with Maoism and later described his younger self as “a leftist in terms of emotional affinity.” He managed to insinuate himself as a key animator on Takahata’s feature directorial debut, Horus, Prince of the Sun—part psychological thriller, part socialist allegory, in which the inhabitants of a small village band together to defeat an evil sorcerer. The production stretched three years with delays and racked up record expenses, during which time Miyazaki married a fellow key animator, Akemi Ota, and had a son, Goro. Frustrated with Takahata and the union, Toei executives gave the film, praised internationally for its technical sophistication, a ten-day run in theaters.

After their second son was born, Miyazaki insisted Ota quit her job to raise their family—though she was his senior at the company and made more money, and he had assured her they would both have careers. This broken promise scarred their relationship. The tradeoff was that Miyazaki barely saw his children as they were growing up. “I would get up in the morning after the children had gone to school and return at night after they had gone to bed,” he recalled. “There was a while when I went to work even on Sundays. That meant we didn’t see each other until the film I was working on was done.”

Clements argues that Toei, because it kept a large staff on payroll but could not always keep them busy, served as a training ground for a generation of animators who had time to experiment and learn from one another between projects. Many went on to found studios of their own. After leaving Toei in 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata made adaptation after adaptation, mostly classics of Western children’s literature, for the studios A-Production and Nippon. Takahata’s most ambitious project during these years was Heidi, Girl of the Alps, for which Miyazaki did layout and scene design. A television series, it ran for a year and was dubbed into twenty languages. Miyazaki maintains that Heidi, and not the heartbreaking Grave of the Fireflies, was Takahata’s finest work.

In 1978 Miyazaki adapted an American sci-fi novel as an adventure series, Future Boy Conan. He employed a trope that he’d repeat several times—boy with indefatigable strength and unwavering loyalty forms bond with girl with mysterious powers—with Conan and Lana, who meet in a postapocalyptic world and overthrow the remnants of Industria, the regime that had nuked it. Miyazaki has said that during these years he thought of his sons as his first audience, though by the time he’d completed a show or a film they’d usually outgrown it. In truth, he was making films for himself: “We animators are involved in this occupation because we have things that were left undone in our childhood…. Those who fully graduated from their childhood leave it behind.”

In 1981 Miyazaki was commissioned to write a serialized manga for Tokuma Shoten’s journal Animage. His star as a filmmaker was rising after his feature directorial debut, The Castle of Cagliostro, an entry in the popular Lupin III franchise. But manga still offered an outlet to make one’s name as an artist by affording complete ownership and control. He wanted to achieve something that could “only be done with manga,” and he did it with painstakingly inked panels crammed with text and a minutely realized science-fiction world. Miyazaki also proposed a looser, less time-consuming style to his editor at Animage, Toshio Suzuki, but Suzuki, who was already envisioning it as a feature film, encouraged his ambition.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is an epic, sprawling, violent story, and not for children, though I pulled it off the shelf when I was eight: the princess of a peaceful kingdom is conscripted into a war over dwindling resources, traversing a postapocalyptic landscape where warring tribes attack each other with biological weapons and refugees make treacherous migrations. Encroaching on all sides is a toxic jungle, populated by insects the size of buildings, and a tsunami slime mold that engulfs villages. Nausicaä alone seems capable of empathy for all the earth’s ruined creatures—even the mold—and in return they receive her as a messiah. At the time that he conceived Nausicaä, Miyazaki was “angry about the general state of the world…. In addition to being upset by environmental problems, I was also concerned about where humanity was headed, and especially about the state of Japan. Most of all, I suspect, I was angered at the state of my own self.” Nausicaä was his tool for thinking, and he outfitted her with a wind glider for nimble flight: “I hope that I can somehow bring this young heroine into a world of peace and freedom.”

4.

The solitary artisan makes a regular appearance in Miyazaki’s films, but so does the service worker, the bustling workshop, the hierarchical company, the industrial concern. The medium can encompass all. Animation is an industrial art, through which even an auteur’s vision is broken down into its constituent parts and realized by a team on an assembly line. The sensibility of a Miyazaki film is as much the poster-paint backgrounds of Kazuo Oga, the color designs of Michiyo Yasuda, Joe Hisaishi’s scores; but it is also executed by key animators who distill character and pose, inbetweeners who draw the intervening frames that simulate motion, tracers who transfer the drawings to acetate, painters, and finishers who check and touch up cels. The films’ subject matter may be totally original or liberally adapted, but it is always mediated by the environs in which Miyazaki has spent his life, the microcosm of the studio: “What is happening in Ghibli is happening in Tokyo. What is happening in Tokyo is happening throughout Japan. What is happening in Japan is probably happening throughout the world,” he has said.

Studio Ghibli was founded in 1985 as a subsidiary of the publishing company Tokuma Shoten to produce Miyazaki and Takahata’s feature films, after Topcraft, the studio that had just made the adaptation of Nausicaä, folded. Takahata was averse to having an official stake in the company, believing that a director should not be a member of a studio and preferring a position akin to an artist in residence. He refused to actually sign the Tokuma deal. “A real creator,” he told Miyazaki, “shouldn’t place his seal on a document like this.”

The great difference between the two men was that Takahata did not draw, and relied entirely on a production staff to execute his exacting vision, while Miyazaki remained at heart a key animator for the rest of his career. According to Suzuki, who became the brain of Ghibli’s business end, Miyazaki was unnervingly suggestible as a director, ready to defer to the opinions of others on major plot points and soaking up ideas from the people around him.6 Better able to work on deadline than Takahata, he had a more practical conception of their new enterprise and believed that filmmaking was as much a business as an art and must pay for itself at the box office. “Companies are just conduits for money,” he told the first team of seventy workers, mostly contractors. “What’s important is that you’re doing what you want and that you’re gaining skills. If Ghibli ceases to appeal to you, then just quit.”

The higher-ups were simpatico. “Money?” the president of Tokuma once said to Suzuki. “It’s nothing but paper,” and “the banks have plenty of that.” Ghibli had inherited the debt of another failed venture by the company, and its first task was to dig itself out of a hole. The studio would only make features, as they brought in the most money and allowed for longer breaks between projects. Miyazaki’s profits from Nausicaä and then his personal savings were soon drained to produce The Story of Yanagawa’s Canals, Takahata’s meticulously researched documentary on the restoration of the titular canals (another one-year project that took three), necessitating a blockbuster to keep the studio solvent.

With Castle in the Sky, Miyazaki delivered the kind of wild adventure that at the time epitomized his strengths as an animator: virtuosic escapes, slapstick brawls, and biblical firepower, delivered on the wings of diesel-punk airships. Pazu, a miner’s apprentice, befriends Sheeta, a girl whose crystal amulet enables levitation and is the key to a legendary city in the sky. Pirates and men in dark suits are after the crystal, which was once extracted from the very hills where Pazu’s crew scours exhausted shafts for ore. By the time Miyazaki was developing the story, which was inspired in part by the failed miner’s strike in Wales, where he went to scout locations, his union days were receding behind him: “In Japan, the idea of workers with a true sense of solidarity…is a thing of the past.”

Operating as though each film could be its last, Ghibli would hire around seventy people and let them go once production was complete. The directors would then take time off to come up with their next idea, and the cycle would repeat. By the early 1990s the need to formalize the business was apparent to Miyazaki: “We can no longer overcome inferior working conditions by staff spirit alone.” Kiki’s box office, the highest in Japan that year, had unexpectedly liberated Ghibli from debt, and the studio shifted from contracts to salaries, boosting benefits and pay for animators but sacrificing the breaks that they were accustomed to taking between films.

Steve Alpert, who served as Ghibli’s international sales man and was the only gaijin, or foreigner, employed by the studio, observed that when he joined in 1996, “Japanese companies then still worked a six-day week. Overtime, if required, was not compensated, even for hourly workers. Vacations and holidays, though earned, were rarely taken.” During the last stage of production, after the director had finally decided how the film should end, the killer weeks that had once driven animators at Toei to unionize reared their head:

the animators and back-end production staff began violating Japan’s labor laws and working an illegal number of hours to finish the film. When the animators were ordered to go home and get some sleep, they either pretended to leave and snuck back to their desks, or just outright refused. The production support staff were keeping the same hours as the animators, even those who didn’t have any more actual work to do on the film. It was about both solidarity with your comrades who had to work and the unspoken code of traditional Japanese peer pressure: if everyone else is working, so are you, even if you don’t have any work to do.7

Miyazaki’s favored plot device is the contract of employment. Porco is under contract with Mediterranean cruise lines to protect their ships from seaplane pirates. The pirates are in business together, sharing the spoils from heists, although each outfit is “responsible for their own expenses.” Porco’s relationship to the pirates is strictly business—“I’m a pig. I don’t fight for honor, I fight for a paycheck”—and it’s in his interest to keep them in the air. He has just made his last payment on his plane to the bank when Curtis, an American gun for hire, is contracted by the pirates to take him out. Curtis is “trouble” because his motivations are not only financial; he flies for fame and glory, and Porco is his prize.

Miyazaki always conjures a fantasy of refuge for his characters that’s not an escape from work, but a place where their work belongs to them alone: Ursula’s cabin in the woods, Howl’s castle stepping into the mist, Porco’s secret hideaway in a sheltered cove in the Adriatic. Nausicaä is tempted to abandon her struggle and make a home with the forest people who live deep in the toxic jungle, in harmony with its ecosystems. But the refuge is always infiltrated, the fantasy always punctured. To rebuild his totaled plane Porco is forced to go to Italy, where he’s a wanted man for deserting the Italian Air Force (“I’d rather be a pig than a fascist”). He hands over all his cash to the Piccolo company, his trusted shop in Milan.

Piccolo employs a multigenerational, all-female staff to rebuild Porco’s plane, the men of Milan having been forced elsewhere for work when the Depression hit. In an exhilarating montage we see them planing wood, welding struts, and spraying red paint, as well as cooking vats of pasta, while Porco rocks a baby in a cradle. What he doesn’t bargain for, when he agrees to let Fio do the job, is that he won’t be able to leave the shop without her: she builds a hatch for herself in the deck so she can come along to make repairs, saying “I’m responsible for this plane.”

In its promotion, Ghibli touted the fact that Porco Rosso had been “made by an army of beautiful women.” Takahata had tied up the principal staff on Only Yesterday, a film about a woman who takes time off from her office job to harvest safflowers on a farm; the studio had never before made two films at once. Miyazaki expanded the women’s bathrooms for the growing female contingent and later installed a nursery. Some had been promoted, but many were housewives contracted to do “piece work,” tasks that are paid by the frame and were, as Rayna Denison notes in her recent book Studio Ghibli: An Industrial History, part of a trend of deprofessionalization that pushed women in animation “to the margins.”8 Suzuki said Miyazaki recognized that “it was women who worked their fingers to the bone to ensure the animation was completed.”

In a lecture Miyazaki gave at Tokuma Shoten in 1982, he told a laudatory story about the finish inspector he had worked with on Heidi. Her job (men could do this job, he noted, but it was nearly always a woman) was to check every frame of the show for flaws and mistakes. She regularly stayed overnight at the studio, working on two hours of sleep to get through seven thousand cels a week. The situation clearly amounted to a labor violation, but it was compounded by a combination of pressures: on top of the high frame rate of Heidi and the weekly deadlines of television production, she insisted on working alone. Miyazaki admitted that “I found myself asking her to do more and more work because she was someone I could utterly depend on.” She was eventually hospitalized, only to return to work after a few days.

In January 1998 Yoshifumi Kondo, who had worked with Miyazaki and Takahata since Lupin III and in whom they’d placed hopes of succession at Ghibli, died of an aneurysm. He was forty-seven. At the crematorium, another animator said that it was Takahata who had killed him. There was no question that he had suffered decades of overwork, during which he had made himself invaluable on Only Yesterday and Porco Rosso; while the directors customarily took monthslong breaks to recover between films, Kondo went directly from wrapping Whisper of the Heart to directing animation and supervising for the studio’s most ambitious film to date, Princess Mononoke.9 Miyazaki’s eulogy is almost shocking for its candor: “Kon-chan didn’t stop moving his pencil, withstanding his pain. In many ways, in our profession, we wear ourselves out, and once we get through this final rap, we can take a brief rest, and we can start working again—so I had assumed.” Miyazaki announced his retirement shortly thereafter, before returning to make Spirited Away.

The contract binds people to each other, or keeps them apart; it compels action, or prevents it; it may be desperately sought only in order to be escaped. “Can’t you give me a job? Please, I just want to work!” Chihiro begs Yubaba, the sorceress who runs the bathhouse, who finally relents and promises to work her to death. In signing the contract, Chihiro assumes a new identity as an employee. “Your name belongs to me now,” Yubaba tells her.

The story goes that Miyazaki was so struck by the apathy of a coworker’s daughter that he decided to create a film for her, one that would “trace the reality in which ten-year-old girls live, as well as to trace the reality of their minds.” The film he made is a coming-of-age story embedded in a parable of Japan’s financial crisis. Chihiro and her parents stumble upon an abandoned theme park as they’re moving to their house in a new development; the park, built in the early 1990s, turns out to be haunted by spirits. Her parents, armed with “credit cards and cash,” gorge themselves at a buffet reserved for the park’s clientele and are turned into pigs; Chihiro enters into her contract with Yubaba to save them. Everyone in this world is either a worker or a customer, and those who are neither simply disappear.

During one of her shifts scrubbing floors in the bathhouse, Chihiro lets in No-Face, a dangerous spirit with the power to mint gold. With its bottomless purse and an appetite that grows the more it feeds, it quickly consumes everything the bathhouse has to offer, plus several of its workers. Refusing No-Face’s money, Chihiro is the only one who can purge its reckless consumption and save the bathhouse. This projectile-vomiting black hole could be an avatar for the Bank of Japan, which contributed to an asset price bubble that tanked the nation’s economy. Between 1985 and 1991 the value of land in Japan increased as much as fiftyfold before the real estate market crashed. All of No-Face’s gold turns to dirt. Chihiro leaves the bathhouse on a train over land that is literally underwater; but what she finds at the end of the line is, unexpectedly, a warm home that welcomes her in. The train used to run in both directions, but at some point the ties between work and home were severed.

One could imagine that this stark portrayal was intended to prepare children growing up in the Lost Decades to inherit a weakened economy, their parents’ debts, and a service job with no end in sight. But the idea to make Chihiro a worker came from a broadcast documentary Miyazaki watched about child labor in Peru. He’d wanted to make a film that kids anywhere in the world could understand; he pointed out that in Japan, “the idea that children don’t have to work is really very new.”

The bathhouse is Ghibli, and despite its exploitative contracts and even deadly risks, it is not an altogether brutal place. For every nightmare there is a triumph, and Yubaba knows how to animate as well as intimidate her workers. When what begins as a hazing for Chihiro—bathing a customer so disgusting that food spoils in his vicinity—becomes an opportunity for wild profit, the boss breaks out a pair of tessen fans and leads the staff in a collective effort to pull a landfill’s worth of garbage from the body of what turns out to be the god of a polluted river. The bathhouse is where Chihiro finds courage and self-respect. Yet it is also a world apart. Time moves differently there, and it’s not clear whether she stays for days, weeks, or months. She begins to forget her parents, and the reason she is working. She nearly forgets her name. Bai-Niang is curiously inverted in Spirited Away as the shapeshifting dragon boy, Haku, who helps Chihiro escape. Chihiro’s love breaks the spell that enslaves Haku to Yubaba, but it’s when she recognizes him as the spirit of a river she once visited as a small child that he is truly free of his own contract.

What does a director owe to those below the line? The only thing that can justify such sacrifice—if indeed it can—is the quality of the product. An American animator who left New York for the Japanese anime industry reported, after being hospitalized three times from overwork, that “everything about my life is utterly horrible, however the artist in me is completely satisfied.” Yet high standards are another vicious cycle, inherent in the ambition, articulated by Miyazaki in his 1982 encomium to the finish inspector on Heidi, that the show should “go beyond the limitations of normal television.” For animation to transcend its limits required that animators transcend theirs. “She adapted,” Miyazaki added; he expressed regret that he had never gotten to work with her again.

Ghibli was conceived as a one-off, obsolete if its auteurs ever died or retired. Its ambition secured its survival, but every film has been make or break. It is a tragic irony that Miyazaki, who was so invested in making the studio a refuge, developed a reputation as a controlling and hot-tempered boss. The dynamic that plagues the industry at large is said to be the expectation of directors who work themselves sick that everyone else will follow. Mamoru Oshii, the director of Ghost in the Shell, said that Ghibli was the Kremlin. “The more talented you are, the more he demands,” cautioned one animator working on The Wind Rises. “If there’s anything in you that you want to protect, you may not want to be around him long.” The studio has never had a union.

5.

Syndication of the complete Nausicaä manga from 1982 to 1994 eclipsed the production of the Nausicaä film, Castle in the Sky, My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Porco Rosso, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. As she probed deeper into the secrets of the forest, Miyazaki came to dread drawing the installments, and never knew where the plot was going, saying that “Nausicaä’s confusion is also my own confusion.” By the end the glider is gone and she’s traveling in the palm of a god warrior, an artificial life form and weapon that was created by—and destroyed—the previous human civilization. Discovering a time capsule left by those militant forebears in order to reestablish their society after the earth’s purification, Nausicaä destroys it with its own technology. She has found out all the world’s secrets, but knowing them doesn’t change, or make easier, the task before her. “No matter how difficult it is,” she tells her followers, “we must live.”

Miyazaki said that spending fourteen years on Nausicaä allowed him to make his “lighter” works. But it was in these films that his sober preoccupations—fascism, war, environmental collapse—found a more practical approach. Clements has noted in Miyazaki’s early essays “the shadows of Marxist structuralism, lamenting the passing of the primitive Communism of the good old days when animators supposedly made animation for animation’s sake, decrying the proletarianization of labor in the animation business.” But by 1992 Miyazaki claimed to have succumbed to a “nihilism based on realism,” no longer believing that a worker revolution could solve the problems he was thinking about. “I don’t think I abandoned Marxism because of any change in my position within society,” he told an interviewer in 1994. “On the contrary, I feel that it came from having written Nausicaä.”

That year, in a speech to the Association of Scenario Writers, he cautioned against the urge toward completism in a medium that offers a canvas without limit:

you will find included not only your daily life, but world affairs, politics, and even economics…. You may not be able to easily integrate everything—even the things that you are most interested in and are the foundation of your world—but the whole world is also struggling because it can’t do this; it’s normal that you can’t either.

Having closed Nausicaä’s epic, Miyazaki started over with a different environmental fable. Rather than burden a lone, infallible heroine with the reconciliation of the world’s brutal contradictions, Miyazaki distilled the story’s conflict to a tension between two characters: Ashitaka, a young chieftain who sets out to save himself and his village from the sudden wrath of the forest’s ancient spirits, and San, a woman raised by wolves who believes she can renounce her own humanity. Princess Mononoke tells a story of early industrialization, a transition that is presented as inevitable, or at least unstoppable: the gods, including the haunted boar who attacked Ashitaka’s village, have been aggressed by the deforestation and mining necessary to iron production. But industry is not inherently corrupt. Lady Eboshi, who runs the ironworks, employs sex workers at her bellows and lepers who turn the metal into firearms. The work gives them dignity and protection from roving samurai, and even Ashitaka, collateral of Eboshi’s crusade, decides Irontown can be redeemed.

The central debate among Japanese Marxists during the 1930s was how Japan had transitioned so rapidly from isolationist feudalism to high-intensity capitalism in the Meiji Restoration of the late nineteenth century, and why, despite the strength of the economy, workers there earned some of the lowest wages in the industrialized world. The transition transformed the environment of Japan. Chelsea Emery has aptly read Mononoke through Marx’s theory of the “metabolic rift,” the alienation of human labor from the natural resources that sustain it.10 But by setting that rift in a fantasy of the fourteenth century, before encroachment by the West, Miyazaki suggests that humanity’s alienation from nature is older and deeper than capitalism, even intrinsic to what it means to be human. For him, problems of labor and the environment are always contiguous. Somewhat fittingly, Mononoke forced Ghibli to modernize, subsequently abandoning hand-painted acetate for digital ink, and end a principled isolationism, courting international distribution (Harvey Weinstein) to cover its record costs.

Mononoke answered the challenge of Takahata’s 1994 environmental message film, Pom Poko. In mockumentary style, a band of raccoons oppose the development of their forest for housing by resurrecting their mythic art of transformation. They haunt the human community with a campaign of illusion that ultimately inspires delight rather than terror and penitence. The film seems to ask whether animation can do anything more than entertain its audience. The raccoons expend tremendous energy to transform, which they replenish with hamburgers and tempura; when, to survive, some choose to live in human form and enter the workforce, they chug energy drinks to banish the telltale dark circles under their eyes.

The two films both end with the hopeful spectacle of deforested hillsides becoming green with new growth. But it’s Miyazaki’s 1988 feature My Neighbor Totoro that has had the most tangible influence on conservation in Japan. Its depiction of two sisters exploring their new country home and befriending a gentle nature spirit, Totoro, inspired a movement to maintain local forests and waterways and a surge of interest in the sustainable satoyama model of farming. The beginning of any reading of Totoro, however, must be that Miyazaki was not raised in the countryside. Animators who had been, like Hideo Ogata, were critical of the film’s depiction of rural Saitama: ten-year-old Satsuki and her younger sister, Mei, run around bare-limbed, as though the woods are free of biting insects. The realism of the setting was otherwise accomplished by Oga, who painted the backgrounds from his childhood memories of Akita prefecture. The time and place is a fantasy: it appears to be the late 1950s, but Miyazaki says that it is set “before television.”

The Kusakabe family has left Tokyo so that their ailing mother can recover from a serious illness: tuberculosis was a disease of Japan’s industrial centers. Their new house is haunted by soot, but not only that; with its Western-style sunroom, Miyazaki imagined it as a place where someone sick had died. He said that he didn’t “have happy episodes from my childhood that I want to depict,” but he gave Satsuki his own burden: when his mother was sick, Hayao apparently took on her household duties and care of his siblings. Satsuki takes up the work of the home that is still a form of play: wiping wooden floors, stamping laundry with her feet, preparing bento boxes for her father and sister. Yet as the weight of this role she’s instinctively taken settles on her we see her harden with stress and worry, fighting with her sister, for whom she is increasingly a maternal figure rather than a peer.

The girls eat vegetables that they harvest from their neighbor’s farm, and Mei becomes convinced that the ear of corn she picked herself will nourish her mother back to health and restore the balance of their family. As eager as she is to follow Satsuki into adulthood, Mei is also the one who pulls her sister back to childhood’s refuge and magic: the woods are home to gentle beasts that only the young can see. What is magic but the suspension of the laws of physics, growth without loss? The morning after their night with Totoro, who urged their garden to grow into an enormous tree and flew them around the countryside, the sisters awake to see there is no tree, but the seeds they planted have sprouted. “It was only a dream!” Satsuki concludes. “It wasn’t a dream!” says Mei.

6.

Hayao Miyazaki is eighty-two. Each film he has made since his first retirement announcement in 1998 (he has now retired six times) has seemed to address some unfinished business; he made Spirited Away to reckon with a deadly workplace, he made Howl’s Moving Castle for his wife, he made Ponyo because he had not yet made a film for very young children. The Wind Rises, a manga story of the Mitsubishi engineer who designed the Zero—the fighter plane Miyazaki’s own family had built—crossed with the life of the novelist Tatsuo Hori, was a retirement passion project syndicated in a hobby magazine. He did not intend to make it into a film, but he couldn’t stay away from Ghibli, which had temporarily halted production when he left in 2014.

The Wind Rises self-consciously answers the mystery at the heart of Castle in the Sky, to which it serves as a sort of prequel. In the earlier film, humankind, engineering ever more advanced machinery and tapping ever deeper into the resources of the earth, built a beautiful utopia—Laputa—that was also the vessel of a world-ending power. The children who discover Laputa’s ruins are astonished that its laser-shooting winged robots are otherwise occupied tending to a giant garden and rescuing birds’ nests. The image of a broken robot from Laputa, under study by the military, is closely recalled by a dream sequence in which Jiro stands over his ruined plane, spread on the floor as though for an autopsy.

Joe Hisaishi reprises the Laputa theme for the scene in which Jiro goes to the train station to meet his fiancée, Nahoko, who is so weak she collapses on the platform. She has come down from a sanatorium in the mountains to support Jiro as he finishes work on the Zero. In order to sleep under the same roof in his boss’s house, where Jiro is living, the couple must marry. “I knew it,” Nahoko says, as Jiro sits up late beside her bed refining his design. “You work better when you’re holding my hand.” Jiro then asks his tubercular wife if he can smoke a cigarette.

One of the film’s only other jokes is Jiro’s halfhearted suggestion to his build team that the plane’s design would be lighter if they took out the guns. Another is his partner’s: “To work hard at the office, you need a family at home.” Ten thousand Zeros were built, and 650 were used in kamikaze flights. That technologies of death, too, are products of love is the cynical but logical extension of what amounts to a theory of human nature in Miyazaki’s work. Jiro’s childhood yearning to build flying machines can only find expression in wartime. Jiro is a pacifist, but the film at no point suggests that he is a hypocrite for making fighter planes, or a coward for taking the military’s money when the rest of the country is starving. “People who design airplanes and machines…no matter how much they believe what they do is good, the winds of time eventually turn them into tools of industrial civilization,” Miyazaki said. “Animation too. Today all of humanity’s dreams are cursed somehow.”

Famously averse to professional acting talent, he cast another animator, Hideaki Anno, to voice soft-spoken Jiro. Anno got his start as a key animator on Nausicaä, picturing the god warrior’s fire of heaven as a laser beam that erupts into a mushroom cloud on impact. He went on to create Neon Genesis Evangelion, a mecha-psychodrama about children who are trained to defend humanity from alien monsters by piloting enormous weaponized robots. The children repeatedly ask themselves why they suffer the physical and mental stress of piloting the robots—why they kill. One of them arrives at an answer in the show’s last episodes, rendered in sketchy stills as budget cuts hampered production: “Because it allows me to exist as myself.”

7.

Howl’s Moving Castle has perplexed critics, all the more because Miyazaki once called it his favorite. The film is based on a fantasy novel by the British writer Diana Wynne Jones, who said of the adaptation that Miyazaki “understood my books in a way that nobody else has ever done.” She went on to explain that the story is about the transcendent power of love. Yet surely what grabbed him was Jones’s depiction of the home as a site of production. From the first pages, her characters are aware of the exploitation of their labor and dissatisfied with the ways their lives have been compromised by it. Sophie, an apprentice in her family’s hat shop, is transformed into an old woman by the jealous Witch of the Waste just as she is beginning to agitate for a fair wage. She almost finds a sense of relief in the new start afforded by the curse, but the theft of her productive years is an outrage that must be challenged.

Trying to get them back, Sophie finds her way to the castle of the wizard Howl and makes a bargain with the fire in his hearth. The fire demon, Calcifer, is bound to the castle and holds it together, and will use its powers to help her if she can break its contract with Howl, the terms of which it can’t reveal:

“Don’t you get anything out of this contract at all?” she said.

“I wouldn’t have entered into it if I didn’t,” said the demon, flickering sadly. “But I wouldn’t have done if I’d known what it would be like. I’m being exploited.”

The moving castle is a fortress to be defended, a machine that runs on combustion, and a business out of which Howl and his apprentice, Markl, sell charms and spells. Sophie offers her services as a cleaning lady and finds solidarity with Calcifer and Markl serving the capricious master of the house, a playboy and spendthrift who hates to work and uses his magic “for entirely selfish reasons.” Howl is indebted to the monarchy of a fantasy kingdom, which sponsored his apprenticeship as a wizard, and to whom he signed an oath “to report when summoned.” When he breaches his contract by refusing to lend his magic to the war effort, the government attempts to strip him of his powers on the basis that he has become a danger to society.

Sophie: Tell him this war is pointless, and you refuse to take part, eh?

Howl: You obviously have no idea what these people are like.

Howl is frequently derided as “lazy” and “selfish” for his reluctance to participate in transactional relationships; in fact, he exhausts himself every night sabotaging the king’s army, battling other wizards who have turned themselves into weapons. The invasion of Iraq began while Howl was in production, and Miyazaki engulfs its characters in a senseless war, including scenes of aerial bombardment, based on what turns out to be a misunderstanding. He has said that adults “shouldn’t be showing children antiwar films to salve our own conscience,” and Howl’s Moving Castle isn’t one. Howl’s guerrilla attacks don’t stop the bombing, but his crusade against war itself is slowly eroding his humanity: the demon’s power he wields corrupts righteousness into a violent addiction. Where Nausicaä engaged in war on every front in an effort to redirect and extinguish it, Sophie’s plea is self-preservation: “Don’t fight, let’s run.”

In the book, Sophie discovers she possesses an unstudied magical gift for bestowing and restoring life. Miyazaki never makes her powers explicit, but like all of his characters she has a singular talent and is searching for a vocation. Howl offers one in the form of a field of flowers that is an unsubtle token of his care for her. “With all the flowers you’ve got in this valley, you could easily open up a flower shop! I’m sure you’d be good at it,” he condescends. She tells him what she wants instead: “I know I can be of help to you.” After examining the working lives of artists, engineers, bakers, miners, and writers, Miyazaki finally considers the implications of what he once said ruefully about his own marriage: “you have to have a talent for family life or for being in love.”

In breaking their contracts, Sophie transforms this group of workers into a family, one that even comes to include the defanged Witch of the Waste. Howl uses his magic to transform the castle from a bachelor pad into a single-family home, transposing it onto the frame of the house and shop where Sophie grew up. In a conventional romance, this act—the playboy domesticated—should signal victory, and Sophie’s younger self peeks through as though the spell has been broken. But there’s a telling line, as she inspects her new bedroom and recognizes it as the very workroom in which she used to decorate hats, without pay, for the family business: “Perfect for a cleaning lady.” She smashes the home to pieces when Howl starts playing the hero to protect it from an air raid.

“In personal life, people have absolute power over each other,” Gillian Rose writes, “whereas in professional life, beyond the terms of the contract, people have authority, the power to make one another comply in ways which may be perceived as legitimate or illegitimate.” Or, in Jones’s formulation:

“And you’ll exploit me,” Sophie said.

“And then you’ll cut up all my suits to teach me,” said Howl.

While Jones’s Howl was a young man when he entered into his contract with Calcifer, Miyazaki’s was a child. To discover its terms Sophie must journey back in time to the particular loss of innocence that Miyazaki is most concerned with, the moment when the spirit is harnessed to ambition, when a child gives up his heart for fuel; a journey that is the signal task of a lover, as well as the end to which animation is a means.