1.

Stockton Street in Brooklyn is bounded on one end by Sumner Houses, a public housing development home to 2,400 people, and doesn’t get very far before it is cut off by Broadway Avenue, a major thoroughfare with trains clattering on overhead tracks. It’s right where Bedford-Stuyvesant meets Bushwick—a poor area that is gentrifying quickly. Despite its small size, the block displays a patchwork of competing visions for how space in the city should be used. There’s an upscale wine bar, a community garden where an anarchist collective distributes groceries, an empty luxury apartment building called The Stockton, and an unfinished Blink Fitness where around five hundred migrants, most of them from Latin America and West Africa, have been living since late June.

In the last two years hundreds of thousands of people around the world fleeing violence, political repression, collapsing economies, and natural disasters have taken an overland route from Latin America to the United States to surrender themselves to border authorities and request asylum. Given the US’s constricted immigration policy, this has become one of the only ways for people with few resources to enter the country, even though asylum was essentially banned during the Trump administration and remains severely restricted under Biden. Over 90,000 asylum seekers have made it to New York City, mostly on long bus rides. Some have traveled to New York of their own volition, while others have been sent by Texas governor Greg Abbott as a political provocation.

Many of those migrants have quickly slipped into city life, but about 54,000 are currently being housed under the mandate of New York City’s forty-year-old Right to Shelter law—a provision, unique among major cities, guaranteeing a bed in a shelter that meets certain minimum standards, within a day, to anyone who asks. Migrants have been put up in a combination of homeless shelters, emergency shelters in hotels and other semipermanent locations, and “respite centers” like the one on Stockton Street, which often violate the terms of Right to Shelter by lacking basic amenities like showers.

Initially Mayor Eric Adams’s administration said that these sites were merely temporary holding rooms for people awaiting transfer to better-resourced shelters, but they have since taken on a more permanent function. In a recent city council oversight hearing, Zachary Iscol, the commissioner of emergency management, was asked how long migrants would be housed in respite centers. “There’s no maximum amount of time,” he said. “It’s when space becomes available at other places.”

The Stockton Street location—a seven-story commercial building whose owner, the property management company Transition Acquisitions, filed permits before the pandemic but finished construction last year—has concrete floors and, migrants reported recently, only one working toilet. When I visited in the first week of July, there had been a mobile shower trailer downstairs for a week, but it wasn’t functioning. A small portable washroom on the sidewalk on Broadway was shut with a padlock that said “do not remove.”

No one was sure when they would be moved, and the days of sleeping on cots close together in an open room, unable to wash, were stretching on. The city has at times been evasive about how many respite centers there are, but in late June Iscol said there are eleven, housing about three thousand people (the mayor’s press office did not respond to a question about the latest version of these numbers). There are reports that the city may soon open two tent shelters in Queens housing a thousand people each, one at Aqueduct Racetrack and one at the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, which is a fifteen-minute drive from the nearest subway stop. Both plans have been met with pushback from locals.

Many of the men at 359 Stockton are Muslim, and the lack of water, which they need to perform ablution before prayer, was particularly distressing. “It’s really a shame,” said Suleiman, a man in his mid-thirties from Mauritania, speaking in Portuguese as Diane Enobabor, a cultural worker and migrant advocate, translated. (The names of all asylum seekers interviewed for this article have been changed.) “You’re sleeping next to your neighbor who hasn’t showered as well. Why are we being treated like criminals? We’re not criminals, we are just looking for a better life.” He had gone around the neighborhood trying to find a place to wash, but people wouldn’t open up their homes. Men had tried to shower at a public pool a twenty-minute walk away, but they were turned away because they needed flip-flops, a lock, and swim trunks with mesh to enter. (After Gothamist and Documented reported on the lack of shower access, the shelter arranged for the pool to open to the men for a few hours before its public opening, but the timing was difficult for men who had managed to find jobs). Suleiman said workers in the respite center would rudely cover their noses with their shirts while checking people in. “Feio, feio,” he said a number of times—ugly.

Advertisement

There were numerous other problems, he said. Some of the men had been scammed by someone who approached them on the street and offered to sell an affordable SIM card. (With no Wi-Fi in the building, they needed a way to get in touch with their families.) Food was paltry, unfamiliar, and sometimes not halal. Storekeepers were impatient when the men couldn’t speak English. The asylum seekers knew they needed to fill out their application papers, but they weren’t sure how. When they asked the workers at the shelter, they were told it would cost $5,000 to file. Advocates had heard from other men that AC was intermittent, and the heat and noise in the communal room made it difficult to rest. Lights would be turned on and off throughout the night, apparently to prevent theft. “They told us in America we would be free,” said one migrant man who walked over. “We are humans, we are not animals.”

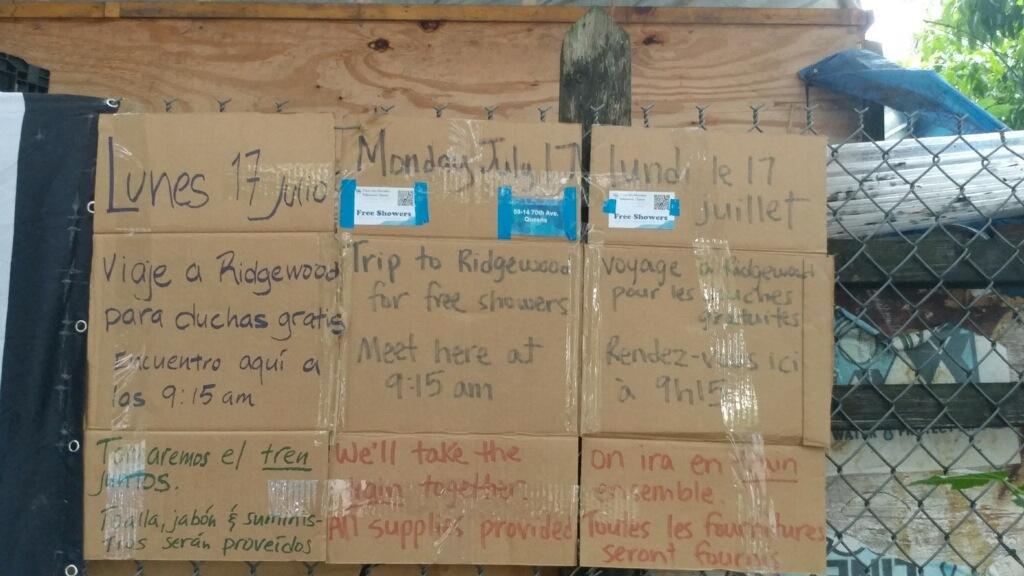

In the first days that the migrants arrived, the community came together to plug some of the gaps left by the state. Bushwick City Farms, the community garden, became a space for migrants to gather. Volunteers at the garden rented two portable toilets for $400 each per month, set up a water jug on a stand for handwashing, built out a cooking area, and bought bulk groceries so the men could prepare communal meals of rice and meat. They organized donation drives for food and clothing and connected with migrant advocacy groups who were able to provide translation services and arrange for assistance with paperwork. They purchased flip-flops, locks, and swim trunks with mesh.

Days after volunteers at the garden alerted her that migrants had arrived at the Stockton Street shelter, Enobabor cofounded a group called the Black and Arab Migrant Solidarity Alliance with a fellow activist named Rana Fayez to advocate for long-distance Black and Arab migrants, who she said not only faced racism and xenophobia but also had unaddressed religious needs, as well as issues accessing translation services. The West African men staying in the shelter mostly spoke some combination of Arabic, French and Wolof. One man spoke only Pulaar, another only Tigrinya. “Mauritania is not something that comes to the top of people’s minds when they think ‘immigrant,’” Enobabor said. “And so there’s no understanding of the cultural nuances of folks from this particular region.” A national group with a similar mission, the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI), was also coordinating aid for migrants at the garden.

Local residents were confused about the migrants’ arrival; the city, Enobabor said, gave them no notice that five hundred people were about to join the community. (“We conducted outreach ahead of opening,” Kate Smart, deputy communications director for the mayor’s office, wrote me. “We don’t have notice when or who is being sent to NYC and so it’s a fast-moving fluid situation to be able to help everyone.”) Members of the garden had some warning only because they have contacts with groups that monitor shelter transfers. Several weeks earlier Mariel Acosta, a volunteer with the garden, noticed people who looked like city workers coming to prepare the building. She said she was a neighbor and asked if there was going to be a shelter on the block. “They said, ‘yeah,’ but wouldn’t say more,” she remembered.

Many respite centers have been set up extremely hastily. In the same hearing, Iscol described beginning lease negotiations for one building at 4 PM, moving people in by midnight, “and continu[ing] to build out infrastructure for longer-duration stays with people staying in those facilities, and that has become sort of normal at the pace that we’re doing this.” But in the case of the Stockton shelter, there was clearly more lead time that could have been used to prepare better living conditions. Enobabor also wished that more thought had gone into placing a shelter in this area, which has little public space other than the community garden and is already stretched for resources. Nonetheless, people have been welcoming. Enobabor said that residents of Sumner Houses pooled their EBT points and bought chicken for the men to cook. “Everyone’s interacting,” she said. “It’s been a very interesting social experiment, for the good.”

Many of the men spent time working in Central America before coming to the US, but the anti-Black racism and violence they faced was too severe for them to stay. Melissa Johnson, an organizer at BAJI, wondered if New York City was doing much better. “If you’re denying people the access to showers, running water, AC, what is that saying about the state? Do they actually want to make sure their lives are safe, to allow them to integrate into our societies?” she asked. “Or are we placing them in the same kind of precarity and vulnerability that will likely [cause them to be] detained and then deported?”

Advertisement

2.

Immigration has always been a fundamental part of New York. The city shed nearly a million residents over the course of the 1970s, and the US-born population stagnated for decades until brisk immigration finally brought the city’s population back to its 1950s peak. By 2009, 36 percent of the city was foreign-born. Immigrants have a higher rate of participation in the workforce than do native-born residents, and economists widely agree that their labor power benefits the economy, especially in the aging US.

The reason that the current wave of migration is attracting attention is that recent arrivals are entering the shelter system at higher rates than in the past. David Dyssegaard Kallick, director of the Immigration Research Initiative, told me that this is thought to be largely because people are fleeing crises rather than moving for opportunity, and thus lack the existing social connections that would make it possible to double or triple up in an apartment with friends or relatives. There is not a large existing Venezuelan community in New York, for example, though Venezuelans are now the second-most common nationality coming over the border.

“The city is being destroyed by the migrant crisis,” is how Adams has taken to summarizing the situation. In response to criticisms that asylum seekers are being housed in illegal and inhumane conditions, Adams and his spokespeople have said that they don’t have the resources to do any better. There is a performative quality to the city’s search for shelter locations; officials repeatedly suggest that they’ve left no stone unturned. They have thrown out the possibility of using the gutted Flatiron Building, which has no heat or bathrooms, and Rikers Island, which evokes a detainment center and would make it extremely difficult for migrants to access the rest of the city. (Migrants were temporarily evacuated from a shuttered prison in Harlem after the plumbing exploded three days after men moved in.) Adams flirted with the idea of using Gracie Mansion, before saying that it was merely a symbolic gesture. “I think leading the challenge of the migrant problem is both substantive and symbolic and as I always said, ‘Good generals lead from the front’…. The symbolism of saying, ‘I’m willing to put a homeless family in Gracie’ is that symbolism.”

Questions about space are at the center of the conflict around the asylum seekers’ arrivals—whether the city still has it, for whom, and at what price. Adams has taken to saying that there is “no more room at the inn,” a phrase that both evokes turning away the innocent and, more to his purpose, suggests that New York City is a hotel with a finite number of beds available rather than a dynamic landscape of political choices, fluctuating markets, and demographic trends. (Another biblical phrase he now uses to describe the perceived impossibility of housing migrants is “our cup runneth over.”) New York City is shrinking: foreign-born arrivals dropped precipitously as a result of the pandemic and Trump’s harsh immigration policy, which contributed to a net loss of about 400,000 city residents overall between April 2020 and July 2022. And yet over the same period the median rent of a one-bedroom apartment increased by about 12 percent, and it has only continued to climb. “No room” is an evasive way of saying “no affordable housing.”

According to city officials, migrants currently make up about half the shelter population, which means there are another fifty thousand longtime New Yorkers who are unhoused. The shelter census decreased during the pandemic—from an average of about 61,000 people a night in January 2019 to 45,000 three years later—as a result of policies like the state’s eviction moratorium and the city’s offer to put vulnerable unhoused people in hotel rooms. Dave Giffen, the executive director of the Coalition for the Homeless, argues that the administration should have anticipated that shelter capacity would need to increase as those protections were removed.

There would be more room for asylum seekers in the shelter system if it didn’t take so long to move longtime residents from shelters into permanent housing. Last year the average length of a stay in a shelter was 509 days for single adults, 534 days for families with children, and 855 days for adult families. Meanwhile there are tens of thousands of low-cost apartments across the city being held vacant for reasons ranging from financial speculation to bureaucratic incompetence. The chief researcher for the city’s Housing Preservation and Development department told The City that in 2021 there were over 88,000 rent-stabilized apartments vacant or off the market—an eighth of all rent-stabilized units in the city. Landlords hoping to wait out 2019’s tenant-friendly rent stabilization laws “warehouse” apartments, or combine multiple vacant ones to remove their stabilized designation.

More recently, Brooklyn councilman Lincoln Restler revealed to the Daily News that there are nearly four thousand empty units in the New York City Housing Authority, and over 2,600 in the city’s supportive housing network, which is specifically intended for the homeless—room for about 15,000 people in total. It now takes NYCHA an average of 258 days to fill an empty apartment, he noted, which is twice as long as it took when Adams entered office. “Management in the shelter is a huge problem,” Giffen told me. Job vacancies have been a major concern across city agencies, but particularly in the Department of Homeless Services: there are 456 fewer people working there now than before the pandemic, and more than a hundred vacant positions were permanently cut from next year’s budget. Giffen said that people in shelters are not getting the help they need from casework staff to fill out applications for housing and rental assistance. “That has been a problem with this administration from day one. There are so many bureaucratic and administrative obstacles. People are spending months and months and months longer in shelters.”

Smart, the mayoral spokesperson, noted that the vacancy rate at NYCHA is currently 4.1 percent and that extensive repair work was taking place across the system as the result of a 2019 agreement with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. “NYCHA’s budget has been also impacted by swelling rent arrears,” she added, “with rent comprising one third of the Authority’s operating budget.” (Public housing residents were prioritized last for emergency rental assistance during Covid-19 under then-governor Andrew Cuomo and received no aid, though the state budget passed this April included $391 million in rental assistance for public housing statewide.)

In May the city council passed four bills that would have expanded eligibility for rental assistance vouchers (called CityFHEPS vouchers) by removing work requirements and changing those for income, making the vouchers available to people still in their apartments but at risk of eviction, reducing the amount that people with rental vouchers have to pay for utilities, and eliminating a rule that people have to reside in a shelter for at least ninety days. Adams met one of these priorities by revoking the ninety-day rule by executive order, touting his own work at moving people out of shelters. But at the same time he increased the work requirement for adult families and, using the second veto of his term, vetoed the full package of city council bills. (On July 13 the council voted 42–8 to override the veto.) He argued that it would be too expensive to pay for more vouchers—though it’s far cheaper to pay for a rental voucher than to house someone in a shelter—and that there’s not an adequate housing supply for an increased number of people with vouchers to rent. Giffen told me that the supply problem was caused in large part by landlords illegally discriminating against tenants with vouchers and that understaffing and bureaucratic inefficiency make it hard to prosecute them.

One might have hoped that the sudden doubling of the shelter population would bring a sense of urgency to the city’s long, shameful inability to address mass homelessness, but instead in May the Adams administration petitioned a judge to suspend the Right to Shelter law. “This is one of the most responsible things any leader can do when they realize the system is buckling and we want to prevent it from collapsing,” he said. But what would ending a longstanding rule that has helped New York avoid the dire street homelessness of other major cities signify if not a system in collapse? “If we want to live in a city that has tens of thousands of people sleeping in boxes along Fifth Avenue, then by all means eliminate Right to Shelter,” Giffen said.

3.

The administration seems to hope that if it repeals Right to Shelter migrants will stop coming to the city. “Since we have a front door that is open, people are finding themselves here,” deputy mayor Anne Williams-Isom said at a recent press conference. Last Wednesday Adams announced that the administration had created “border advocacy flyers” that would be distributed at the southern border, urging migrants not to come to the city. “There is no guarantee we will be able to provide shelter and services to new arrivals,” reads one bullet point, which is not true as long as Right to Shelter stands. Another, more plaintively: “Housing in NYC is very expensive.”

But not only is asylum a human right and immigration the lifeblood of New York, the hazardous journeys that people take to get here also testify to the fact that they will always migrate when they feel they have no choice. Migrants who cross through Central America and Mexico risk kidnapping and frequent extortion by the police or bandits. Luis, a thirty-four-year-old from Nicaragua, said he had been kidnapped for four days while traveling through Juárez. “It was a difficult experience,” he said in Spanish. “They took us to a big ranch, then to another house with all sorts of weapons.”

Since Mexico and other Central American countries restrict visa access for people, such as Venezuelans and Haitians, who belong to nationalities that are currently fleeing to the US in high numbers, migrants often travel first to South America, sometimes working for months or years in Colombia or Brazil until discrimination or difficulty finding sustainable work push them onwards. The 2,500-mile overland journey to the US usually starts in Colombia, where migrants congregate near the country’s border before attempting the Darién Gap, a sixty-six-mile bottleneck of mountainous rainforest between Colombia and Panama that has no roads. Hiking is made hazardous by muddy slopes, swift rivers, snakes, scorpions, and malaria—as well as by violence from paramilitary groups and smugglers, though these are also the people who make the crossing possible.

Ana Martinez de Luco runs Our Home, a community of mobile homes in Staten Island that shelter formerly unhoused people and those with substance abuse issues. Recently the program has been housing asylum-seekers as well, and de Luco relayed some of the stories she had heard about the dangers of the trip. Migrants described “going up mountains where everything was mud,” she said. “You have no way to hold any branch, and people keep slipping…. The moment you slipped you just went down totally, and then no more.” One man told her that he injured his knee in the jungle and couldn’t walk. He told his companions to leave without him, and his brother and brother’s wife carried on, but his partner stayed behind. “He insulted her and threw stones and everything, saying go on, go with them, I will die here and I [would] like to die here, leave me alone,” de Luco said. The woman went to get help and finally managed to carry him to a safer place, where he recovered.

De Luco expressed fear that people arriving in the US are unprepared for the difficulty of life as a migrant here. Now they were having trouble finding housing and feeling stuck without legal work authorization, for which they are only eligible after staying in the country six months. “At times they can work in delis, washing, undocumented,” she said, “but paid $10 an hour. They feel abused because they know $15 is the minimum. The little work you can find, still you find you are being abused. They give you the job nobody else would do.”

4.

On June 23 a large crowd of parents gathered outside Row NYC, a tourist hotel around the block from several Broadway theaters and a Junior’s, to greet their children, who were being dropped off at the hotel in five yellow school buses. A mother and boy dwarfed by his huge Spiderman backpack waited at the door of the bus for two twin girls wearing pink tulle skirts and clutching a giant bunch of helium birthday balloons, including a large silver “4.” A girl clambered on scaffolding while her father held her folder and pencil case, which bore her name in capital letters. No one would argue that Eighth Avenue and Forty-fourth Street is the most relaxing place to drop off numerous small children, but it worked.

The city has set up an “arrival center” at another hotel nearby, the Roosevelt, which closed during the pandemic. Migrants check in and are eventually shuttled to other shelters throughout the city on MTA buses. Until recently the buses would also pick people up from Port Authority, where migrants frequently arrive ill or hungry after a days-long ride, many of them with small children. But on the night of July 4 this service was suddenly revoked. Now National Guardsmen pass out a flier with a screenshot from Google Maps, directing new arrivals to walk nearly a mile across the heart of midtown.

The city’s temporary-residency contracts with over 140 hotels, including Row NYC, have been a boon as many recover from the Covid-era tourism depression. In its haste, the city suspended the traditional competitive bidding process for contracts and has offered some hotels more than market rate to book empty rooms. Bloomberg reported that a Holiday Inn in the Financial District that had recently filed for bankruptcy signed a deal with the city that would increase the hotel’s revenue by $10 million.

Conditions in hotel shelters are considerably better than in respite centers. Luis, staying in a hotel shelter in Staten Island, said that the accommodations were good and that he was grateful the government was paying for a place to stay, though he was having trouble finding a stable job. But the hotel shelters have issues, too. Victoria, thirty-four, from Ecuador, was staying in the same hotel and said that her children weren’t given proper food and that she and other residents were forbidden from cooking in their rooms. Without childcare available, she wasn’t able to work. “The children had to be with me at all times,” she said in Spanish. “They didn’t allow me to leave them with other people who were there…. They would threaten to call the police because the children were left alone. They threatened us with the police as if we were dogs.”

Manuel, twenty-nine, from Nicaragua, had enrolled his children in school. “At first it was hard, but now they are getting used to it,” he said in Spanish. One of them wouldn’t eat the frozen food the hotel provided, but Manuel had found a job and was buying food from outside. (There have been multiple reports from across the city that migrants are being served spoiled food in shelters; this week migrants staged a walkout at a Sheepshead Bay shelter protesting food that had landed multiple residents in the emergency room.) His family had started saving money and was hoping to rent an apartment, but they hadn’t gotten any help with their asylum paperwork at the shelter and he was worried about finding a lawyer, which he had heard would cost thousands of dollars. “We need to file for asylum before our one-year anniversary in the US,” he said. “We have to find a lawyer somehow.”

Recently the Adams administration has seemed dangerously close to throwing up its hands and leaving people on the streets, legally or not. At last Wednesday’s press conference, Adams announced that to ensure hotel shelters have enough space for families, single adult asylum seekers living in the more permanent emergency shelters, known as Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers (HERRCs), will be limited to sixty-day stays, “paired with intensified casework services to help them explore their options and connect with their networks of friends and families.” If that fails, they can reapply for shelter at an arrival center, but Adams and other officials at the same press conference said there is no guarantee they will find a place. Adams suggested that people would have to wait at the arrival center for space to open up. “Is there a bed there? Where do they go?” asked a reporter. “That’s a good question,” said Adams. “Wherever they can find a place to wait. There are no laws that prevent people to wait wherever they can find a place to wait. But right now we have no space, so wherever they can wait, they are waiting.”

5.

In April Adams cited the cost of housing migrants as a reason to threaten cuts of 4 percent to all city agency budgets. The budget his administration ultimately negotiated with the city council avoided many of these reductions and found increased funding for NYCHA and Housing Preservation and Development, meeting a campaign promise to invest $4 billion per year in affordable housing for the first time. But essential services at Rikers were cut, and homeless services providers contracted by the city are expected to reduce their spending by about $29 million per year through 2027. (Smart argued that “the savings DHS achieved…[do] not make it more difficult to help people leave shelters and find permanent housing,” and that “DHS has ample remaining vacancies to hire for critical positions.”)

Adams and city officials have repeatedly said that asylum seekers will cost the city $4.3 billion by next July. The Independent Budget Office has disputed that number, which seems to be based on the idea that the number of migrants in the city’s care will continue to increase at a steady rate—even though people should be exiting the shelter system at a fairly steady rate as well, especially as they approach the six-month mark at which they can receive work authorization. (“Our modeling has been on track,” Smart wrote. She noted that the June budget even raised the estimate by $50 million “due to rapid growth.”) The state has contributed about $1 billion, and FEMA is likely to contribute $100 million. In May the city council predicted that New York will take in $1.8 billion more in revenue than was expected through 2024.

Whatever the city will spend on shelter, it’s certainly a considerable sum. Theo Moore, vice president of policy and programs for the New York Immigration Coalition, said that the state and federal governments should step up to provide more funds:

But really what we need is the mayor to be a convener, the person who is bringing folks from the Hochul and Biden administration together to work towards solutions, and except for scapegoating and trying to pass on blame we haven’t seen him play that role, or with local folks on the ground.

Indeed, despite Adams’s frequent requests for assistance (he has taken to demanding that any city officials who criticize him, especially the progressive comptroller Brad Lander, should spend their time in Washington asking the federal government for funds), the city has at times left members of grassroots organizations that advocate for migrants feeling dismissed. Power Malu, a longtime Lower East Side community organizer who runs a group called Artists Activists Athletes, has been greeting migrants at Port Authority since the immigrant advocate Adama Bah alerted him to the first bus from Texas. He says that he and Bah started doing advocacy work as they realized how few services the city was providing. They would refer people with particular needs to the correct organizations and push city administrators when something fell through the cracks—when, for example, a family was separated and sent to different shelters.

At Port Authority their table became a hub where migrants would ask for information or report problems, until the city abruptly announced that the area would be closed and there would be no place for Malu and other activists at the new Roosevelt Hotel arrival center. “They just said, oh, by the way, we’re shutting down operations at Port Authority and we’re now going to start sending the buses to the intake center,” he said. “They know that we are on the inside, we have all of this information, and for them it was threatening.” Asked for comment, Smart directed me to Port Authority to ask about operations there and wrote, “New Yorkers have stepped up tremendously to help address this crisis and we appreciate all the volunteers who have helped.”

Malu was happy for his work to remain independent from the city, but he didn’t understand why there was so little communication from the Adams administration. “Why would you want to stop an organization that is doing this work when we’re volunteer-based?” he said. “There’s things that advocates can do that regular staff members cannot do because they have to follow protocol, and that allows us to actually make things happen, right now, in real time.”

Around the city, activists and neighbors have jumped in. On a recent visit to Stockton Street, I saw garden volunteers and asylum seekers spend thirty minutes using a combination of English, French, Arabic, gesturing, and Google Translate to establish how to use a laundromat around the corner. There are toilets, handwashing stations, people offering legal advice, food trucks donating halal meat. That grassroots groups have done so much to address problems that city officials haven’t, on a shoestring budget and with only a week’s notice, suggests that this is not an unmanageable crisis, though it’s undeniably a strain on volunteers with full-time jobs.

The city alone cannot solve some of those problems. “On a federal level we need to start rebuilding our welcoming system that was systematically dismantled during the Trump administration,” Moore said. Applying for asylum is an unnecessarily complicated process, and requiring migrants to wait for six months before granting work eligibility causes unnecessary financial distress. The state and federal governments can and should contribute more funds. But it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that the Adams administration, based on political grandstanding and a misguided belief in deterrence, is not strongly motivated to do a good job of serving the city’s newest residents. In a time of federal gridlock, it’s not feasible to punt the issue and let people languish.

On Thursday the city brought in a water truck to fill the mobile shower’s tank and a security guard told Acosta that it would finally be open for use the next day, over three weeks after the shelter opened. (There had been considerable negative press attention, and garden members had been reaching out repeatedly to their city councilman.) Acosta told me via text message that the asylum seekers she had spoken to had been confused about when the showers would be available, and some hadn’t known at all. She asked a security guard how the information had been publicized and said she was told that a few men who knew English had been informed and were expected to have spread the word. Despite the positive development, Acosta said that the men were feeling demoralized after learning about the new sixty-day shelter limit. “They think they’re gonna end up in the streets.”

“People are not a crisis,” Kallick told me. “I have no doubt that the immigrants coming today are going to find a place in the economy.” What will provoke a crisis is denying migrants the initial help they need to gain a foothold in society—say, by placing them in a shelter far from any subways, or making it difficult for them to shower before going to job interviews, or leaving them perplexed over how to apply for work authorization. (Smart said that the city had opened an asylum application help center several weeks ago, which is a step in the right direction, though none of the people I spoke to seemed to have used it or been aware of it.) If migrants never get that help, the financial burden of caring for them in shelters will keep growing, which could ultimately be used as an excuse to gut services or legal protections for all New Yorkers.

According to the standard anti-immigration rhetoric, new arrivals will take away resources from earlier residents. But the arrival of asylum seekers can be better seen as a chance to rethink the city’s housing and resource distribution to make it more livable for all. “This is an opportunity we have to unite the city, and I say it all the time, and I tell it to the migrants when I go on the bus,” said Malu. “I say, you’re going to be blamed for all these things that were happening way before you got here, so don’t believe the hype. We got your backs.”