Come Here (Jai Jumlong), the most recent feature from the Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong, opens with a trick of the eye. Glowing in the center of the screen is its visual double, a bright spot of light and motion circumscribed within a darkened frame. But what at first looks like a screen turns out to be the window of a train hurtling through a mountainous landscape. Gradually the sound of the railway becomes the noise of its construction: clanging pickaxes and shoveling coal. The landscape rushes by so quickly that for a moment the train seems to reverse its motion. The film’s journey is not only through space but also through time.

Come Here was inspired by Anocha’s travels to Kanchanaburi, a province in western Thailand where part of the “Death Railway” is still intact. Built in World War II during the Japanese occupation with forced labor from civilians and Allied prisoners of war, the railway claimed a devastating human cost: over 100,000 people are estimated to have lost their lives from overwork, physical abuse, and disease. The film keeps alluding to this history but deferring its explication. Its travelers are four young tourists, vacationing members of a theater troupe. Their journey begins at the Hellfire Pass Memorial Museum, which commemorates a particularly brutal section of the Death Railway, but when they arrive they find it closed for refurbishment. “Where did the railway lead again? Did they ever finish building it?” they ask one another on the adjacent memorial trail, before the film cuts to a site where fragments of the railway ties remain preserved.

The troupe checks into a resort house on the banks of the Kwai River, where they drink, smoke, converse, watch fireworks, playact, and, above all, sleep. The film is attuned to their languorous activities with slow, sumptuous shots that allow texture and rhythm to come to the foreground: the lapping waves of the river; the soft inhalations and tangled limbs of sleeping bodies. But all this aimless repose is also tinged with a sense that the characters don’t belong, that they aren’t inhabiting space so much as passing through it.

This sense is amplified by disappearances and substitutions that fray the boundary between the real and the imagined. A young woman not in the troupe, Way (Waywiree Ittianunkul), ventures out alone at night and gets lost in the forest. When she collapses in distress by the side of a lake, she transforms into Sorn (Sornrapat Patharakorn), one of the troupe’s actors. Elsewhere, on an empty soundstage, workers construct a sparse theatrical set that approximates the vacation house. There the actors restage the evening they have spent together with a cast of three instead of four—Sorn, now missing, is played by one of the remaining actors, Aim (Bhumibhat Thavornsiri). Another actor, Saiparn (Apinya Sakuljaroensuk), seems to describe the film’s own mercurial form when she confesses to Sorn, in a moment that will be restaged on set, that she can’t imagine pursuing theater as her long-term livelihood: “I’d want something more…stable.”

These plotlines cut across each other, double back on themselves, and splinter off in new permutations, as if the weight of the past is preventing any sustained narrative traction. Anocha’s interest is less in historical events themselves than in the silences and impasses they impose on the present. The troupe’s carefree vacationing suggests the disconnect between these contemporary urbanites and the traumatic histories that animate their countryside retreat, but their rehearsals also surface the region’s dormant memories. A sparring match between the boys, acting as various animals, subtly shifts into a more violent register as the scene develops, the camera lingering on their brute determination to force each other to the ground.

*

Since Thailand’s shift from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy in 1932, the country has experienced more successful military coups d’état than any other in modern history. It was under nearly continuous military rule from 1947 until 1973, when a student-led popular uprising overthrew the reigning dictatorship and ushered in a brief era of radical possibility: growing social movements staged mass actions to demand dramatic reforms in labor, education, land policy, and welfare. The backlash was swift. Another coup three years later reinstalled a military government, which escalated armed conflicts with communist guerillas, student activists, and organized labor. A new period of parliamentary governance began in the 1980s, and in 1997 the country adopted a liberal “reform constitution.” But power remained consolidated among elites and income inequality surged to extremes.

The monarchy, meanwhile, was shoring up and expanding its power. Royalists redescribed the monarchy as an ally of “democracy,” a bulwark against the ostensible threats of military dictatorship on the one hand and communism on the other. In the following decades, as corruption scandals inspired widespread distrust of electoral political parties, conservative coalitions co-opted these populist discontents to discredit electoral democracy as such. Instead they called for expanding the monarchy’s power.

Advertisement

In 2006 a royalist coup toppled the elected government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, and since then the alliance between the military and the monarchy has strengthened. After the 2014 removal of the then–prime minister, Thaksin’s sister Yingluck Shinawatra, General Prayuth Chan-ocha seized control of the state in another coup. He has stayed in power by manipulating the law to extend his term limits and stifle political dissent—although this May’s parliamentary elections, which had the largest turnout of any in Thai history, resulted in an astonishing victory for his democratic challengers.

The country’s military rulers have presided over a sociopolitical climate of increasing authoritarianism. Harsh lèse-majesté laws written into Thailand’s criminal code beginning in the early 1900s aim to punish acts deemed critical of the monarchy, and longstanding censorship laws prohibit films deemed injurious to public morality or national security. Under Prayuth such laws have been coupled with a heightened constriction of civil liberties, restrictions on public assembly, and the silencing of dissidents through torture and forced disappearance.

These repressive policies have forced politically minded filmmakers to either use creative techniques of evasion or seek funding and support outside Thailand. Apichatpong Weerasethakul has become an exemplary figure of this persecution. After battling censors and withdrawing more than one of his films from circulation in Thailand, Apichatpong announced in 2015 that he would no longer make films in his homeland. “This government will never give freedom to the people,” he wrote in a 2007 essay lambasting the country’s new Film and Video Act, which replaced a much older censorship law with a new ratings system but retained the state’s capacity to censor and ban films outright. “We are making a pact with the devil.”

Anocha’s indirect treatment of historical trauma might be understood both as a tactical maneuver around such restrictions and as a way of registering how they splinter national memory. But that is just the starting point of her cinematic practice. In their time-bending narrative structures and constantly shifting forms, her films—she has released four features and eleven shorts since 2006—suggest that the past is open not only to violent co-optation and erasure but also to revision. They insist, as the scholar May Adadol Ingawanij writes, that “change takes place, somehow, even in the face of a political petrification that seems all-consuming, terrifyingly spectacular and blinding in its denial of the inevitable.”

*

In interviews Anocha often emphasizes that 1976, the year of her birth, was also the year of the Thammasat University Massacre—the execution of leftist student protesters by police and right-wing militias—and the subsequent military coup that ended the fragile gains of the 1973 popular uprising. Precipitated by the publication of a photograph that was falsely alleged to show students staging a mock hanging of then–crown prince Vajiralonkorn, the massacre was a violent spectacle. After police stormed the campus, wounding hundreds of students, angry mobs lynched protesters in front of enthusiastic crowds. Witnesses documented these murders; one of the most chilling photographs shows onlookers gathered around a man as he beats the body of a hanging student with a folding chair, a perverse appropriation of the students’ play.1 The image won a Pulitzer, but its protagonists—both victim and perpetrator—remain unidentified. One can trace the origins of Anocha’s aesthetic and political sensibility here: to the brutal collapse, during Thammasat, of the boundary between historical events and their representation.

The historian and Thammasat survivor Thongchai Winichakul called the massacre at once “unforgettable” and “unrememberable.”2 The perpetrators have never been brought to justice, and the state’s efforts to control the story—first by persecuting critics and survivors, then by partially recognizing a sanitized account of the event in the name of “unity” and reconciliation—has prevented Thammasat from being fully investigated or discussed in public life, even as it was succeeded by the 1992 massacre of protesters during “Black May” and the crackdown on pro-democracy “Red Shirts” in 2010.

“I tried to pose the question of whether or not one can really feel the pain of others through film,” Anocha reflected in an interview about Come Here. It was an interest that began with her earliest work. Her thesis film, Graceland (2006), follows an Elvis impersonator in Bangkok hitchhiking home with a mysterious stranger. At night in the woods they share a moment of improvised tenderness, but after he undresses her and reveals a large scar on her breast, the woman collapses into his arms in tears, and in the morning he wakes up alone. The stylized trappings of melodrama (lush lighting, swelling music, a woman on the run from an unspoken, violent past) are left behind as Elvis hitchhikes the rest of the way home on the back of a truck. When he arrives he takes off his costume, crawls into bed next to his sleeping family, and, as if he has inherited the stranger’s burden, begins to weep.

Advertisement

After receiving her MFA in filmmaking from Columbia, Anocha returned to Thailand, where she witnessed the 2006 coup. It “shattered” her, she remembered, and prompted her to more explicitly engage with Thai history and politics. Mundane History (Jao nok krajok, 2009), her first feature, depicts the relationship between a young disabled man, Ake (Phakpoom Surapongsanurak), and his male live-in nurse, Pun (Arkaney Cherkam), in a stultifying mansion in Bangkok. Paralyzed from the waist down after an unnamed accident, Ake alternates between sullen, fatigued withdrawal and impetuous, childish rebellions against the painful loss of his autonomy: refusing to dine with his cold, distant father; hurling dishes across the room; staying outside during a downpour.

Scenes of Pun and Ake growing closer are interspersed with ones that remind the viewer of the stark difference in their social positions. Alone in the cramped servants’ quarters, Pun calls his partner to say that everyone in the house is “soulless” and that he wants to quit. But over the course of their relationship Pun goes from being the target of Ake’s outbursts to a cautious collaborator in his rebellions. The two men steal away from the house to view a planetarium show and have stilted conversations in which Pun admits he wanted to be a writer and Ake reveals an aborted film career—gestures that the critic Carmen Gray reads as veiled comments on creative repression in Thailand.

“Is it possible for us to live without a past?” Pun asks Ake. “Without a future as well?” Ake asks in return. Both of them are confined in their circumstances, isolated from the world beyond the mansion’s walls by disability or servitude. But occasionally the past and future interrupt the film’s stagnant present. When Pun finally asks about his accident, Ake falls silent, but as if in response the following sequence shifts into an experimental mode, intercutting and superimposing images of Ake in the hospital with those of protests by the Royalist “Yellow Shirts” who had called for Thaksin’s overthrow. At another point the narrative gives way to footage of a supernova accompanied by noisy, distorted guitar music; the culminating scene is a live cesarean birth.

Intimacy—between strangers, friends, lovers, colleagues, artists and their subjects—has remained Anocha’s preferred subject for approaching political and historical trauma. She describes Come Here as a meditation not only on place but also on love—“a complicated” concept, she has written, in today’s Thailand, where it “is used to describe one’s dutiful relationship to the nation, religion, and king,” the three pillars of Thai state ideology. Love binds the self at once to the state and to other people; it can reproduce dominant social relations but also bring people into contact with what transforms them. For the most part, Anocha’s films center on failures of intimacy—moments of misrecognition, illegibility, and disconnect that call cinema’s capacity to represent “the pain of others” into question. They put particular emphasis on the differences and antagonisms between two kinds of subjects: the contingent, feminized laborers (migrant, seasonal, care, and service workers) who bear the weight of history, and the creative workers (filmmakers, actors, and other performing professionals) who represent it.

In the short film Jai (2007), a young director named Mai sets out to remake Jon Ungpakorn’s 1975 documentary Hara Factory Workers’ Struggle, about the historic takeover of the Hara jeans factory by its striking female workers. Ungpakorn’s film is primarily composed of first-person testimonies from the workers themselves, but Mai casts a movie star to play the protagonist in her fictional remake and reduces the workers to silent extras; gradually Anocha’s film comes to focus not on the star but on one of the extras Mai ignores.

Jai planted the seed for Anocha’s second feature, By the Time It Gets Dark (Dao Khanong, 2016), which follows the attempts of another young director, Ann (played initially by Visra Vichit-Vadakan), to make a film about a Thammasat survivor, Taew (Rassami Paoluengtong). In one conversation Ann worries about the gulf that separates Taew’s experience of “living history,” as she puts it, from her own of “appropriating” it. The film interrogates that distinction. In an early scene, Ann directs a reenactment of a famous photograph of the massacre, which shows soldiers pointing guns at rows of students lying face-down before them. “More brutal!” she calls out over the loudspeaker. “Be more brutal!”

What Anocha calls Ann and Taew’s “lack of bonding” sets the film on a course of relentless deconstruction and recombination. Scenes from the film Ann is making, of students preparing for the Thammasat demonstration, are interwoven with Anocha’s restaging of Ann’s and Taew’s encounters with new actors. A young service worker, Nong (Atchara Suwan), appears across the film’s many narratives as, variously, a barista, a cruise hostess, and a maid. Her labor becomes a foil to that of the young creatives—until the film’s ending, when she appears as a Buddhist nun before getting caught in a glitching frame that disintegrates into an ecstatic web of pixels. Documentary footage of laborers at a tobacco plant collapses into another fiction when one of the workers turns out to be an actor, who later films a scene in bed with a lover—Anocha’s riff on the opening scene of Godard’s Contempt—and then heads to a soundstage to film a music video. The film erupts into a musical number before returning to pick up its tangled threads; in its final shot, a candy-colored landscape slowly fades back into naturalistic color. “At some point,” Anocha said in 2019, “I want the film to attack the audience.”

*

A visually ascetic work, shot in black and white and in the 4:3 aspect ratio of 35mm silent cinema, Come Here mutes the confrontation of Anocha’s earlier features, but the absences that her films all circle—the loss of historical memory, interpersonal detachment—are all the more palpable for its stripped-down form. The soundscape, designed by Ernst Karel, privileges both ambient noise (the lapping water of the river, the rustle of leaves) and recorded sounds from other times (of the railway, the song, a zoo) over dialogue, cluing the audience into layers of history that the characters seem not to sense.

Interspersing the troupe’s activities is travelogue-style footage of the route between Bangkok and Kanchanaburi. The camera takes phantom rides along the Death Railway and down the Kwai River, revealing landscapes devoid of people but bearing their traces: power lines snaking alongside the tracks; the Srinakarin Dam’s steel pipes carving through the mountainside; an abandoned house sinking into the river; the debris of sociality—cigarette butts, empty beers—that the troupe members abandon on the deck of their vacation house. A patriotic Thai song set to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”—“together we can achieve anything so long as we unite as one”—rings out over an empty platform like an unfulfilled promise.

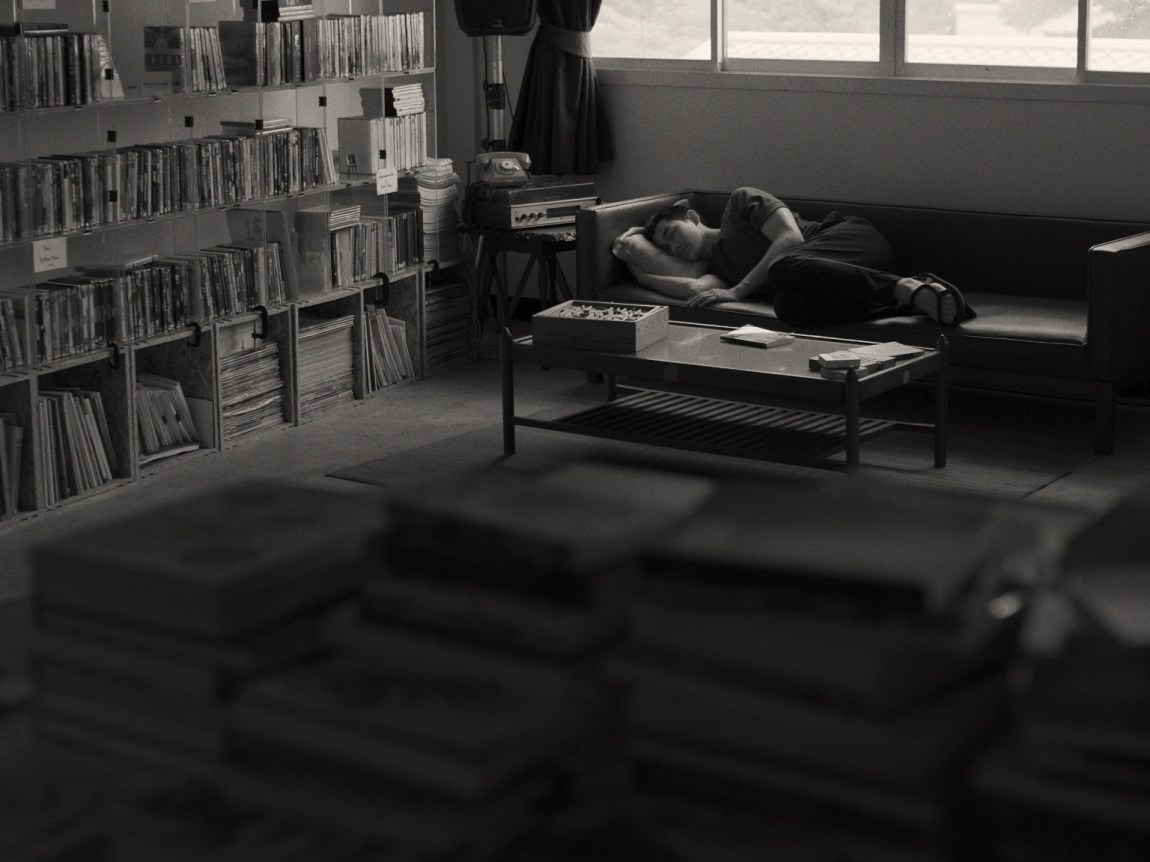

In the final scene, Sorn falls asleep on a couch in the Reading Room, a free contemporary art library and public event space in Bangkok. The film cuts to a long close-up of soil, one of Anocha’s recurring images of rebirth. In moments like these Come Here seems to be addressing an uncertain future, an anticipated audience who might inherit the claims and burdens of historical memory that its characters cannot.

Come Here stops short of suggesting what that future, or that audience, might look like, reflecting a contemporary uncertainty about the world young Thais are inheriting. Resistance to Prayuth’s regime gathered momentum when in 2019 he disqualified his progressive electoral opponent, the Future Forward party leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, from parliament. In February 2020, after Prayuth’s constitutional court ruled to disband Future Forward altogether, the party’s supporters, many of them young students, took to the streets, beginning with a flash-mob demonstration at Thammasat University. Later that year protesters resumed demonstrations that drew on the symbolic force of the Thai past, including on June 24—the anniversary of the 1932 overthrow of the absolute monarchy—and in October, when they commemorated both Thammasat and the student uprising of October 14, 1973.

The arrest of hundreds of protesters under charges including lèse-majesté quieted such public actions in 2022, but this year’s elections sent a strong message of ongoing dissent. Move Forward, the successor to Future Forward, won the largest share of parliamentary seats. Pheu Thai—the party of Thaksin and his successors—came in second place, and military-affiliated parties won a combined total of under 20 percent of the seats.

Move Forward ran on a bold reformist platform: drafting a new constitution, abolishing mandatory military conscription, and amending the country’s lèse-majesté laws to expand Thai citizens’ political and artistic freedoms. This last proposal especially met with strong opposition from the conservative and royalist members of Thailand’s parliament, which currently consists of five hundred elected members and 250 appointed members who regularly side with ruling military and royalist interests. In the first round of voting on July 13, Move Forward’s ministerial candidate, Pita Limjaroenrat, failed to win enough votes to deliver him the premiership, and as parliament readies itself for a repeatedly postponed second vote, it has denied Pita a second bid. On July 19 the constitutional court suspended him from parliament while it investigates a legal complaint about his eligibility. The move, reminiscent of the court’s disqualification of Thanathorn on similar grounds, has already prompted protests.

Anocha continues to film in Thailand, investing in its independent cinema and in particular its experimental short film scene. In addition to teaching film, she cofounded the independent production company Electric Eel Films in 2006 and the film fund Purin Pictures eleven years later. Both support alternative filmmaking, especially by Southeast Asian and female artists. One of Electric Eel’s recent coproductions is Pom Bunsermvicha’s Lemongrass Girl (2021), a short film born out of conversations among Anocha, Pom, and four other filmmakers—Tulapop Saenjaroen, Parinee Buthrasri, Maenum Chagasik, and Aacharee Ungsriwong—about patriarchy and sexism in the film industry. Anocha drafted the script, about a Thai superstition, still common practice on film sets, that a young virgin must plant lemongrass on the set to ward off rain.

Lemongrass Girl takes place on the set of Come Here and builds on its imaginative ground. Pom has described the film’s lack of formal “purity”—it combines documentary scenes of Come Here’s production with a fictional narrative—as suggestive of the arbitrariness of the superstition itself: “It doesn’t even matter if she’s a virgin or not. Either way, it’s a lose-lose situation for the woman.” Either she gets teased for being a virgin or blamed when it rains; her body has in any case become subject to public speculation.

In Lemongrass Girl the ritual is given to Piano, a production assistant. While the technical crew clusters together around monitors and equipment or kills time in easy camaraderie, Piano stays on the margins, alone in the frame as she balances trays of beverages and forages for lemongrass, the last person to take breaks. She is both the only member of the crew who has contact with the world beyond the set and the one who must account for the film’s effect on it. In the woods where Way disappears, Piano receives a phone call that the shoot has disturbed the natural landscape by dislodging some rocks from the mountainside. “Please accept our apologies,” she replies, before taking responsibility: “I should have kept a closer eye on it.”

Lemongrass Girl insists that cinema is not a world apart but a part of the world, threatened by its social hierarchies and historical and political impasses. Anocha’s appearance as herself in Pom’s short, directing scenes from the feature, is her most explicit acknowledgment of the risk of her continued creative labor: complicity with cinema’s tendency to stay indifferent toward the world it inhabits due to its absorption within the world it creates. And yet the short’s mode of production resists such closure. Instead it models a collaborative, protean working method in which the set for one film becomes a chance to beget another one. Lemongrass Girl ends with Piano’s disappearance from the shoot. She is last seen laying down to sleep, as rumbling thunder announces the coming rain. For Anocha, sleep and cinema are both journeys into unknown terrain, laced with threat but also with the promise of transformation. The risk, she insists, is worth taking.