In 2019 the Internet Archive gave me and other Istanbul enthusiasts a great gift: one of its users uploaded all eleven volumes of the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, one of the most eccentric encyclopedias produced in the last century. The first article I read was on the Ağa Hamamı, a Turkish bathhouse a stone’s throw from my writing studio in Beyoğlu. I learned that it was built in the sixteenth century in the classic Ottoman architectural style, that it was at one point run by an Armenian and was sold to a Muslim in 1953, and that “some single men, belonging to the ranks of roughnecks, would use it as a hotel.” The entry described how the playboys, drunkards, and gays of Beyoğlu used to stay the night at the bath and emerge all cleaned up in the morning. It had a captivating mixture of the matter-of-fact voice of an encyclopedia and the informality of a gossip column.

The amateur historian Reşad Ekrem Koçu and his team of authors and artists spent twenty-two years attempting to put together this compendium about the ancient city of his birth. The project’s first phase, from 1944 to 1951, ended in bankruptcy; the second, from 1958 to 1973, concluded shortly before Koçu’s death, leaving the encyclopedia unfinished at the letter G. (The final entry tells the story of “Gökçınar, Mehmed,” a junkie poet from Istanbul who spent eighteen months in prison for possessing an illegal substance and earned the moniker “Hippie Mehmed” after locals noticed him wandering Istanbul’s streets barefoot.) İstanbul Ansiklopedisi has remained out of print in Turkey ever since.

Koçu, a journalist who savored Ottoman history’s most salacious details, first thought of writing a city encyclopedia in the 1940s. His aim, as he put it in the introduction to the first volume in 1946, was to produce a “grand register” of Istanbul. İstanbul Ansiklopedisi is the second known city encyclopedia in history, after William Kent’s An Encyclopedia of London (1937). Unlike Kent’s work, a compilation of the landmarks of pre–World War II London that came to a satisfying conclusion, Koçu’s encyclopedia was destined to stay a work-in-progress: it was an ever-growing palimpsest of Istanbul’s murders, love affairs, real estate debates, pandemics, and more. The gravestone of an ordinary citizen could get an article as detailed as a monumental mosque; a thief from an impoverished neighborhood could be profiled with the same attention as an Ottoman sultan. Bitlisli Ali Çamiç Ağa, who served coffee in his cafe for seventy-three years, gets an entry, as do the attractive young men working at the city’s storied barbershops.

The encyclopedia’s more than six thousand pages include articles on history, architecture, folklore, and literature. Biographies of contemporary figures, such as the bestselling female Turkish writer Nezihe Araz, contain quotes from their subjects gathered through interviews or survey questions. Numerous articles about the Armenian and Greek heritage of the city were written by, respectively, an Armenian contributor, Kevork Pamukciyan, and a Greek one, Neoklis Sarris. Koçu also solicited letters from readers, requesting, for instance, information about the city’s Greek churches. Some articles end with a “Reşad Ekrem Koçu Travel Note” that gives his own reflections on a street or building. In Istanbul: Memories and the City (2003) Orhan Pamuk celebrated these “strange and colorful entries.” He described the encyclopedia as an “unrivaled guide to the city’s soul, for the texture of the prose is the texture of the city itself.”

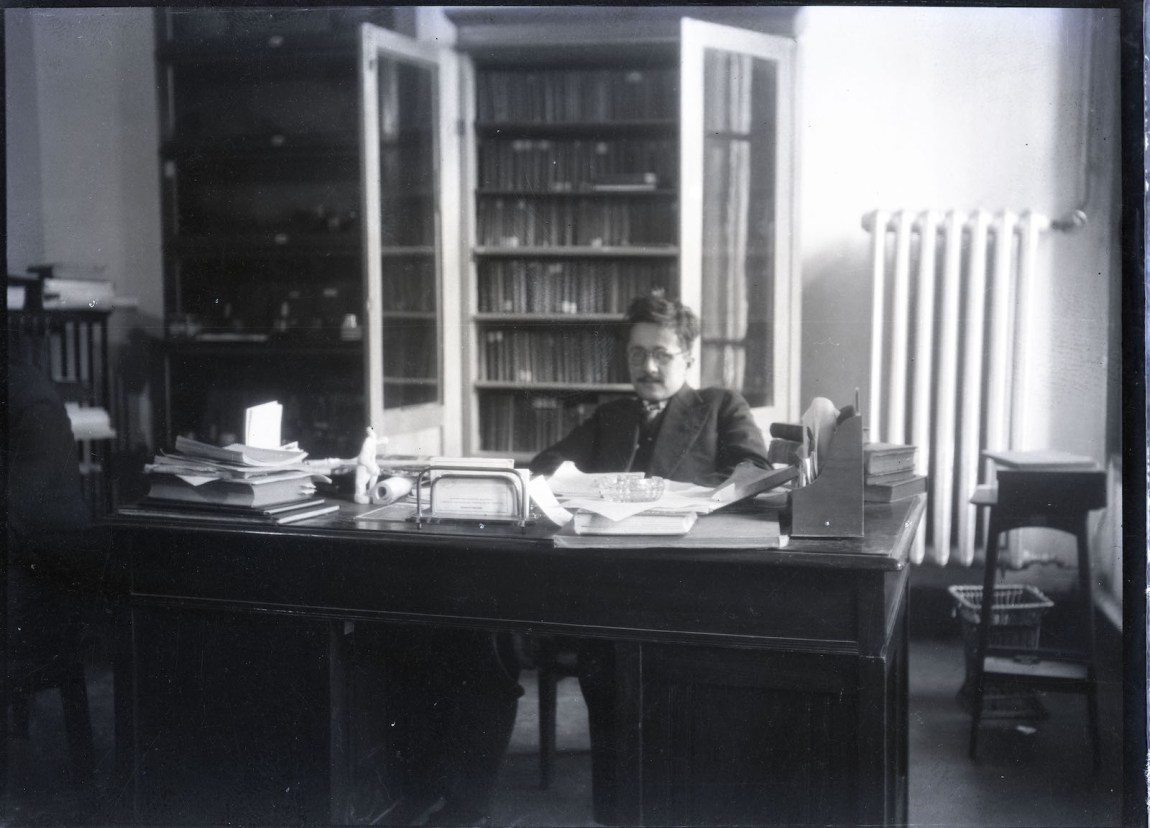

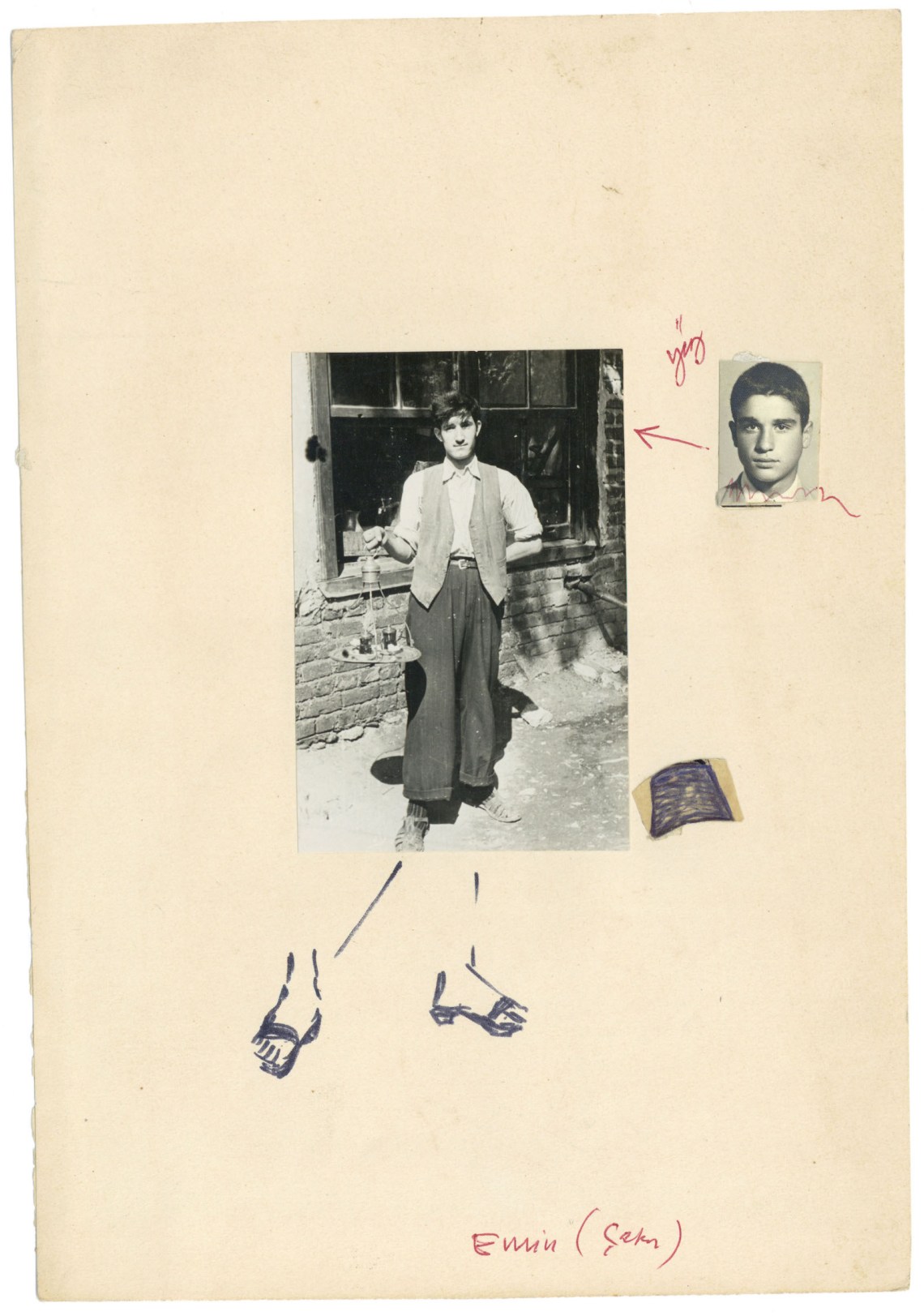

“No Further Records,” a show at Istanbul’s Salt Galata gallery, is part of an archival project that makes public for the first time everything Koçu amassed for the unpublished volumes: article drafts, newspaper clippings, notes, drawings, letters asking for money to support his work. Photographs and manuscript drafts are scattered with appropriate chaos across the exhibition space, with snippets of text offering clues about the encyclopedia’s scope. There are lists, hundreds of them, continuously revised and expanded, on Istanbul’s bathhouses, mosques, graveyards, scholars, barbers, gardeners, wine sellers, weather, spices, flowers, and brigands. The extent of Koçu’s obsession, the curators argue, ensured that his work “would always be incomplete.”

*

For locals of Istanbul today, İstanbul Ansiklopedisi preserves the past of a city that has seen countless urban development projects over the last century. In the 1950s, under the prime minister Adnan Menderes, wide avenues were constructed, historical buildings demolished, and coastal roads built around the Historical Peninsula, the spit of land enclosed by the ancient city walls on one side and by the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Golden Horn on the other. The vision of a “global Istanbul” promoted by Bedrettin Dalan, the city’s mayor in the second half of the 1980s, included razing industrial and residential buildings along the Golden Horn—the estuary that once formed the northern boundary of ancient Byzantium and now separates the Historical Peninsula from new Istanbul—to create new recreational areas, and using bulldozers furnished with Turkish flags to eliminate historic buildings owned by Christians in the Tarlabaşı area, arguing that “it is not our culture, anyway.” Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s projects, first as Istanbul’s mayor and then as president, have been still more destructive: his “Canal Istanbul” initiative, surpassing the Suez and Panama canals in scale, will turn the city’s historic center into an island.

Advertisement

These politicians justified their destruction of historic architecture and neighborhoods with a nationalist reading of Ottoman history. In their telling, atheist republicans led by Turkey’s Europeanizing founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, knowingly abandoned the former seat of the Islamic caliphate to its fate after Turkey became a republic in 1923. The republican founders had been nationalists themselves: inspired by German models, they celebrated purity and discipline and considered the old empire dangerously degenerate. Rulers like Menderes, Dalan, and Erdoğan rejected this nationalist project only to embrace another, predicated on recovering a lost utopia of Ottoman expansionism. Istanbul is central to this revivalist vision. While Atatürk reviled the city as a site of Ottoman debauchery, Erdoğan and his right-wing predecessors embraced it for its connection to the sultans they idolized—Mehmed II, who took Istanbul from the Byzantines in 1453, and Selim, who turned it into the seat of the Islamic caliphate in 1517. They celebrated its legacy by razing its ruins and replacing them with shiny architectural kitsch.

Koçu articulated his own ambition in nationalist terms, dedicating the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi to the five-hundred-year anniversary of the date Mehmed II took Istanbul from Constantine XI and ended the Byzantine Empire: “the Turkish conquest of this great city, which I’m proud to be an inhabitant of for five generations.”1 Unlike Turkey’s official historians, who routinely erase Istanbul’s Armenian and Greek heritage, Koçu showed the full extent of the city’s Armenian and Greek culture before the genocides of the 1910s. Still, he was in other respects a typical Ottomanist, declining to defend Armenian rights or advocate for the recognition of the empire’s atrocities.

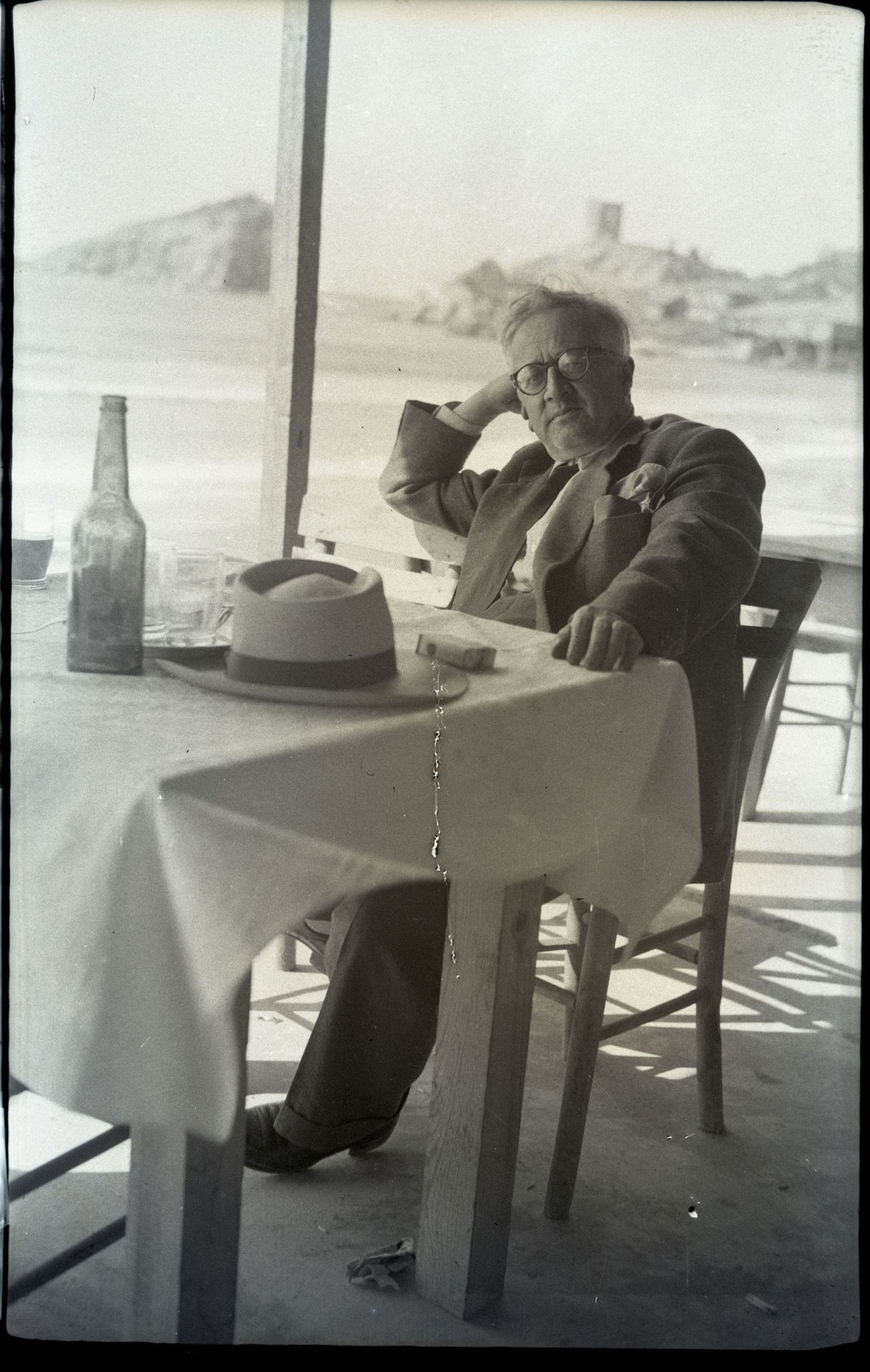

During the 1930s he worked at Dârülfünûn—later to become Istanbul University—as an assistant to the esteemed Ottoman historian Ahmet Refik Altınay. At the time Kemalist historians proposed placing the “Turkish race” at the center of world history, a trend Altınay rejected. In 1933 the government resolved to “reform” the university by cleansing it of Kemalism’s critics, including Altınay. The purge led Koçu, among many other intellectuals, to write critically of Atatürk’s party, the CHP. In his columns for the conservative newspaper Tercüman, he leaned toward the center-right Democrat Party, the CHP’s main rival, whose ranks comprised both disgruntled leftists and conservatives.

Yet the Democrat Party proved to be an even harsher violator of democratic rights when, under Prime Minister Menderes, it came into power in 1950, stoking xenophobia against Turkey’s Jews and Christians, suppressing opposition parties, stifling the press, and, in 1955, orchestrating a pogrom against the city’s remaining Greeks, who eventually fled the country. Koçu’s anger about the party’s urban development program is evident throughout the encyclopedia. He doesn’t hide his disgust in his entry on the Köprü Bathhouse, “an architectural masterpiece that was demolished thanks to the orders of Menderes,” or when he describes the destruction of the Camcılar Mosque in Aksaray as a “huge disaster which some called a development between 1957 and 1959.” These changes were personal for Koçu. Realizing that, over the course of the 1950s, the city in which he had once wandered freely was vanishing, he took on the role of its obituarist. The encyclopedia was a record of his obsessive search for the old Istanbul: its ancient walls, its gardens and flowers, and its locals victimized by modernization.

In 2002 Koçu’s close friend and contributor Semavi Eyice told the newspaper Hürriyet that Koçu had been gay, confirming a suspicion that Koçu’s readers had long harbored. The Turkish historian Murat Bardakçı has said that Koçu was “what the elders used to call a ‘lover of jamal’ [the handsome].” Koçu’s closeted queerness found its best expression in the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, where he uses a colorful, perfumed prose to write about Istanbul’s men, adoringly fetishizing their garments and bodies. One of his articles describes a youth named Eskicigüzeli Yetim Ahmed as a

Advertisement

barefooted boy whose baggy trousers had forty patches, and you could see his skin from the crack of his shirt; in terms of his beauty, he was peachy, his eyebrows furnishing his forehead like a certificate of beauty, his hair like a demoiselle’s, his dark skin made of gold, with coyness in his look, coquetry in the way he speaks, and his body lean like a needle.2

*

A timber merchant bankrolled the first era of the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, and the first fascicle—thirty-two pages and about nine by thirteen inches—appeared in November 1944. The title page includes a list of its contents that encapsulated the spirit of the work:

Istanbul’s Mosques, Masjids, Madrasas, Schools, Libraries, Lodges, Shrines, Churches, Greek Springs, Public Fountains, Palaces, Waterside Mansions, City Mansions, Kiosks, Inns, Bathhouses, Theaters, Coffeehouses, Wine Houses… All of Its Buildings… All of Its Statesmen, Scholars, Poets, Artisans, Businesspeople, Medics, Professors, Hodjas, Dervishes, Priests, Monks, Lunatics, Young Men, Beloveds, Singers, Musicians, Dancers, Male Dancers, Drunkards, Vagabonds, Oil Wrestlers, Fire Brigadiers, Ruffians, Gamblers, Thieves, Outcasts, Beggars, Murderers… All of Its Celebrities… All of Its Mountains, Slopes, Waters, Airs, Promenades, Flower Gardens, Vegetable Gardens… All of Its Natural Beauties and Geographies… Its Streets, Quarters, Neighborhoods… Its Fires, Plagues, Earthquakes, Revolutions, Murders, and Legendary Love Affairs… Customs, Traditions, Garments From Era to Era… Its Slang… Paintings, Poems, Books, Novels, Travelogues About Istanbul… All the Foreign Celebrities Who Visited Istanbul

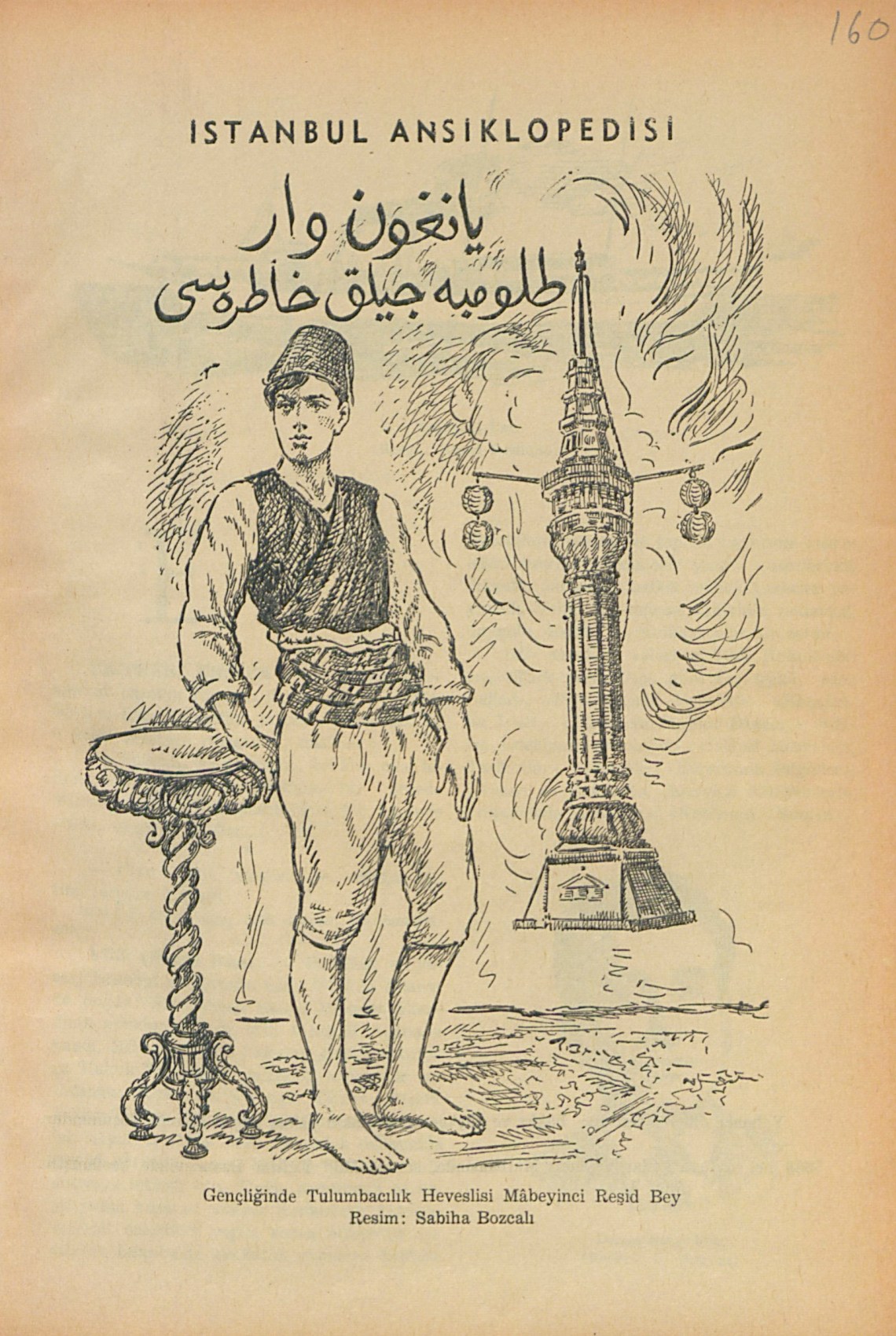

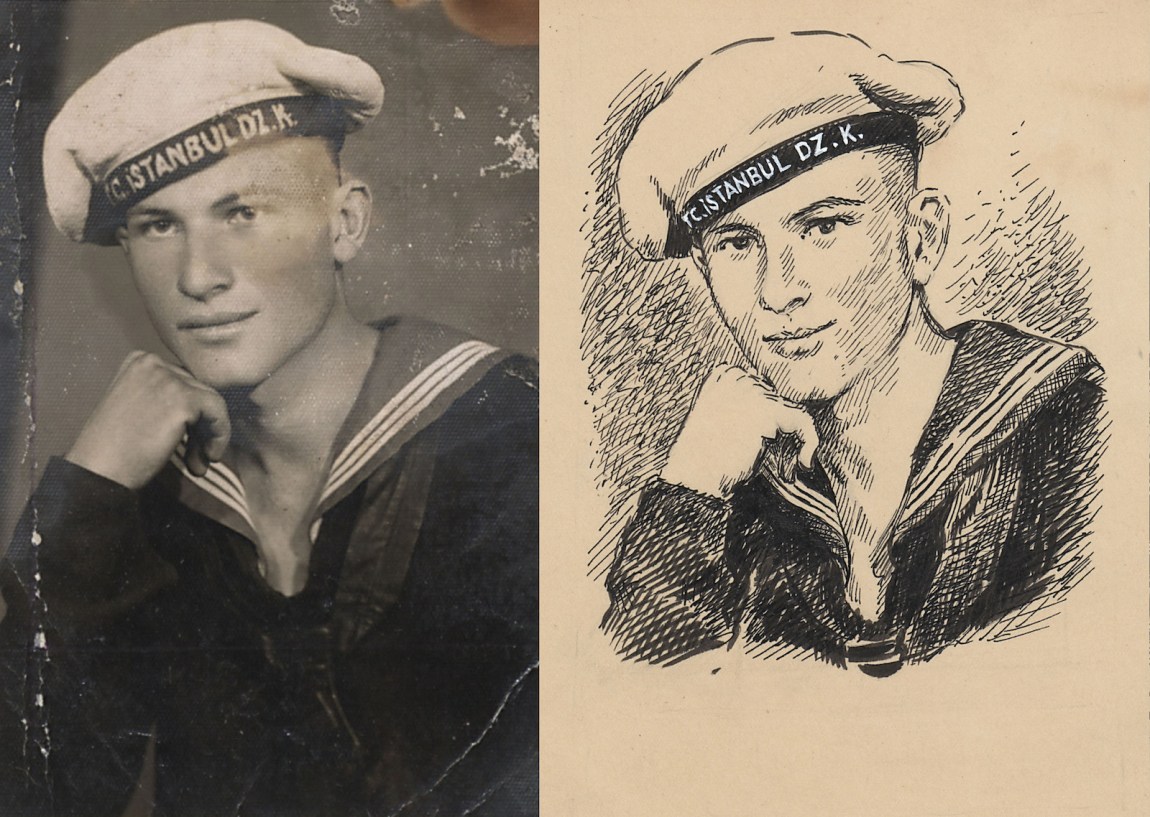

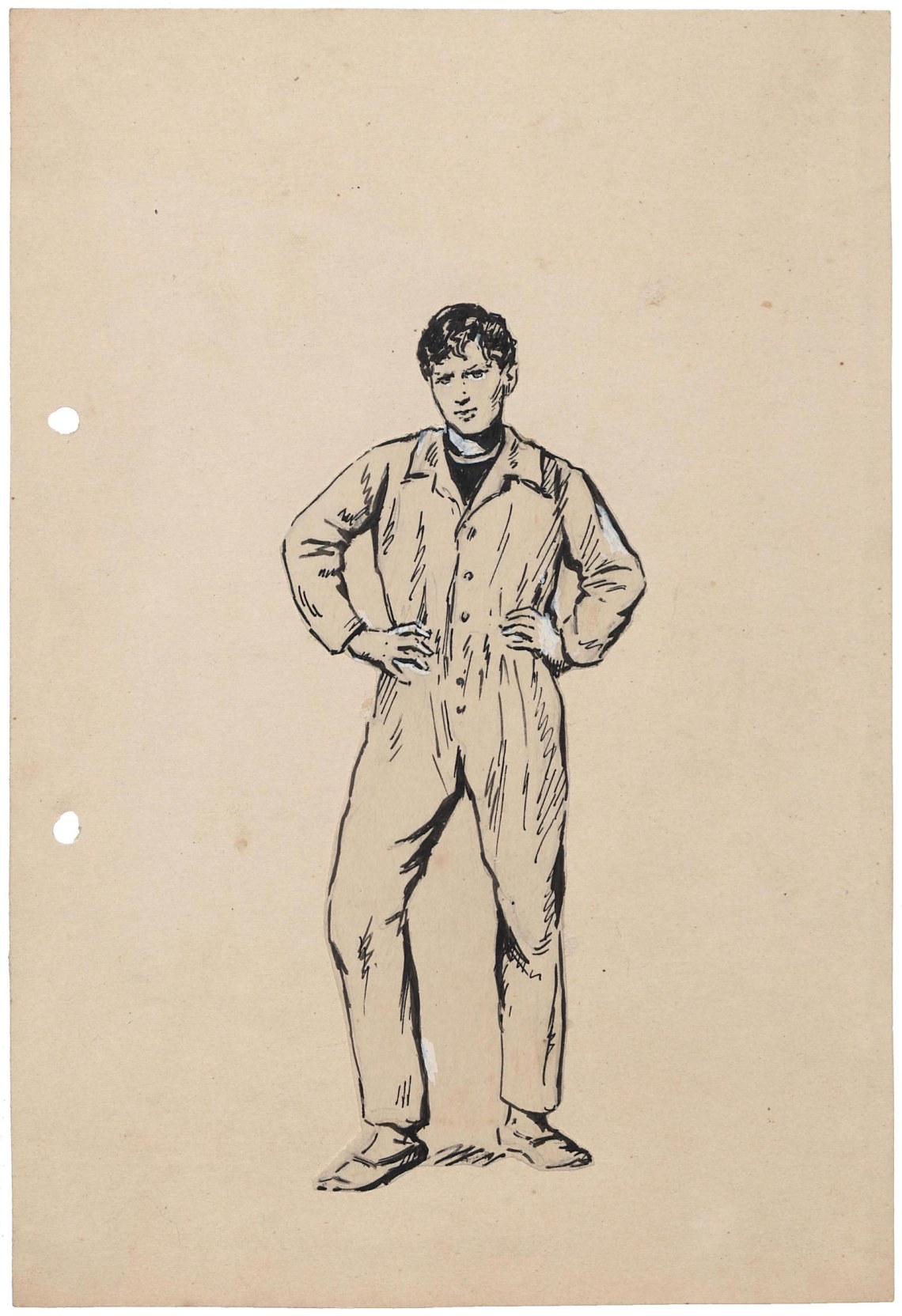

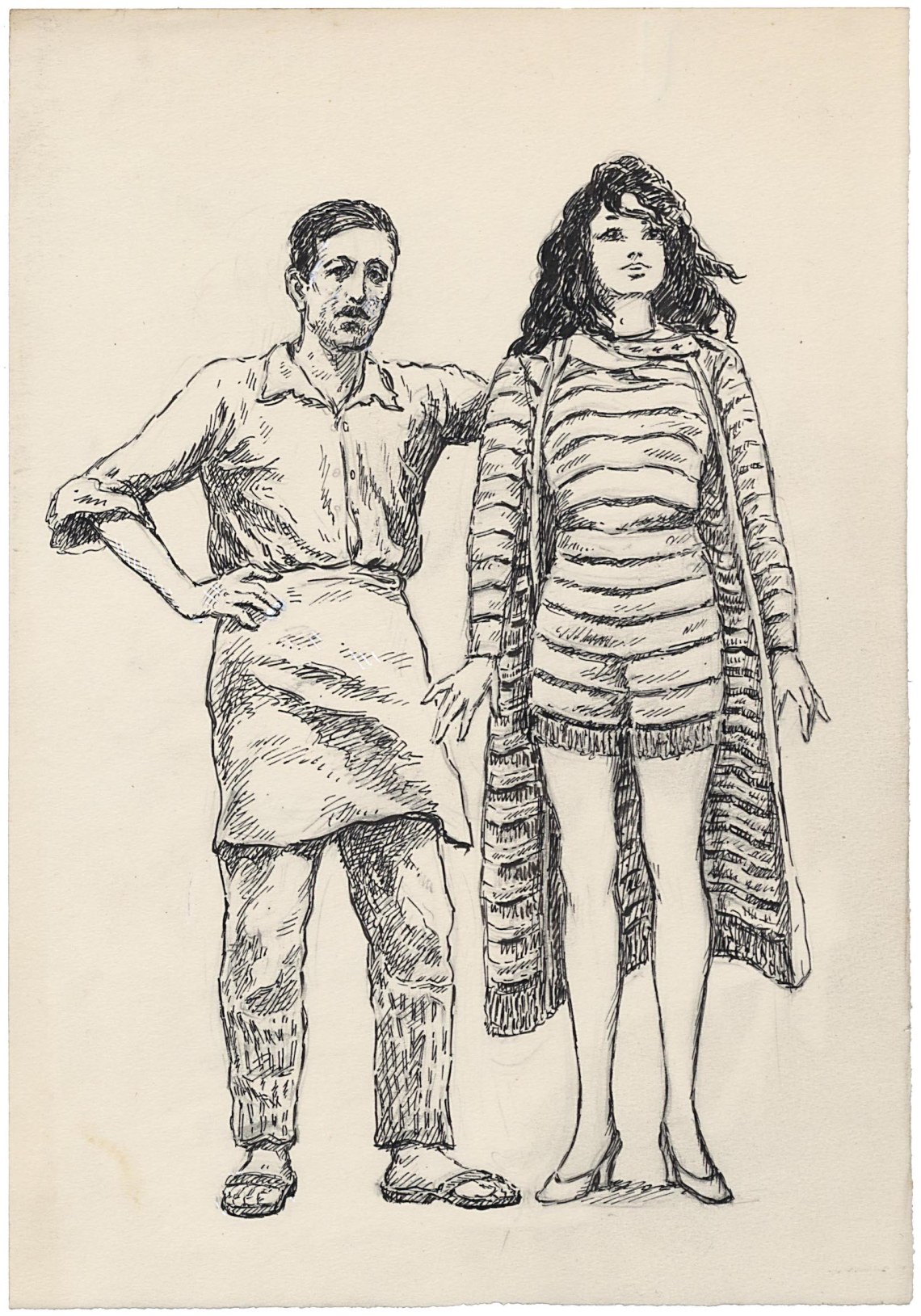

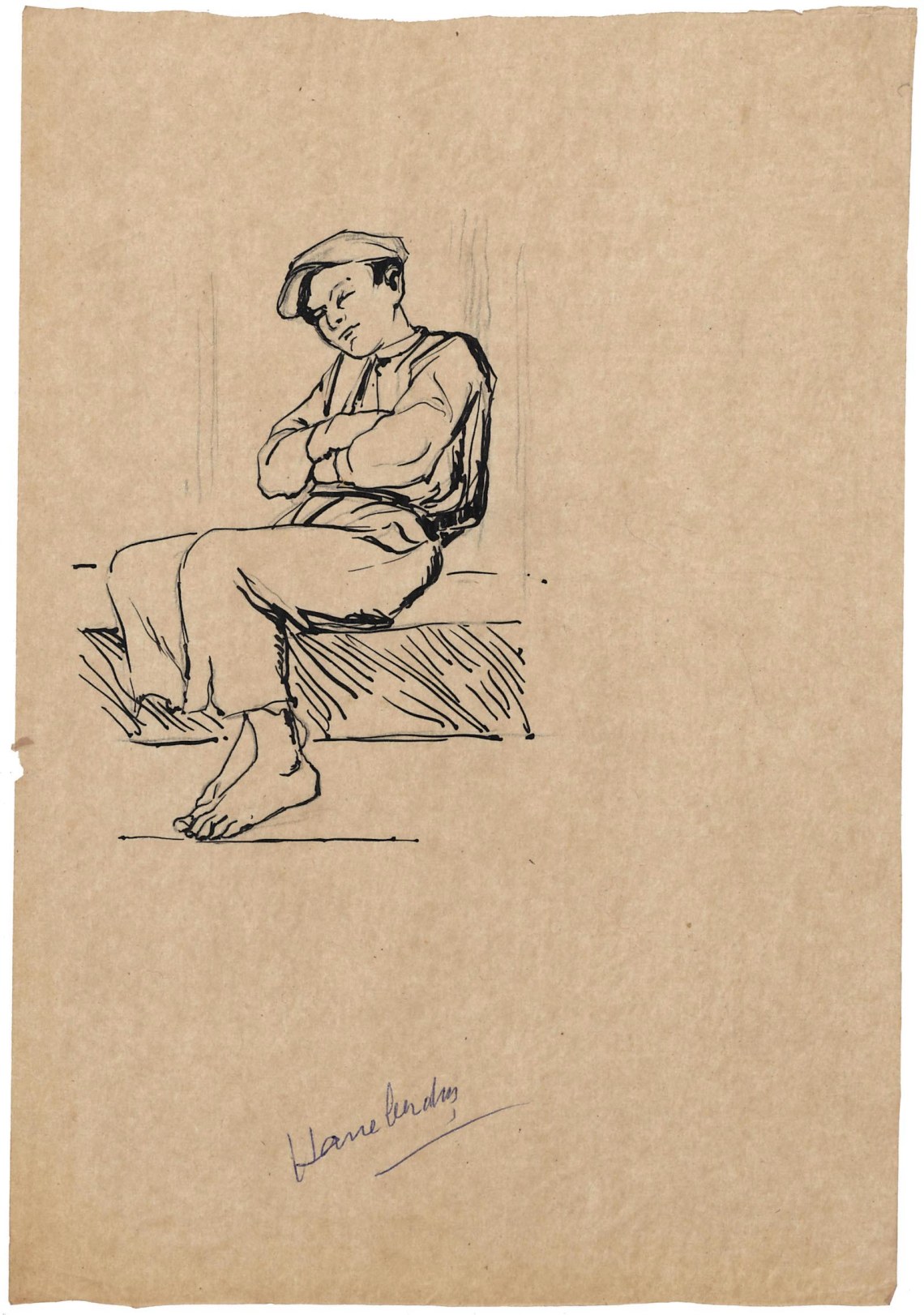

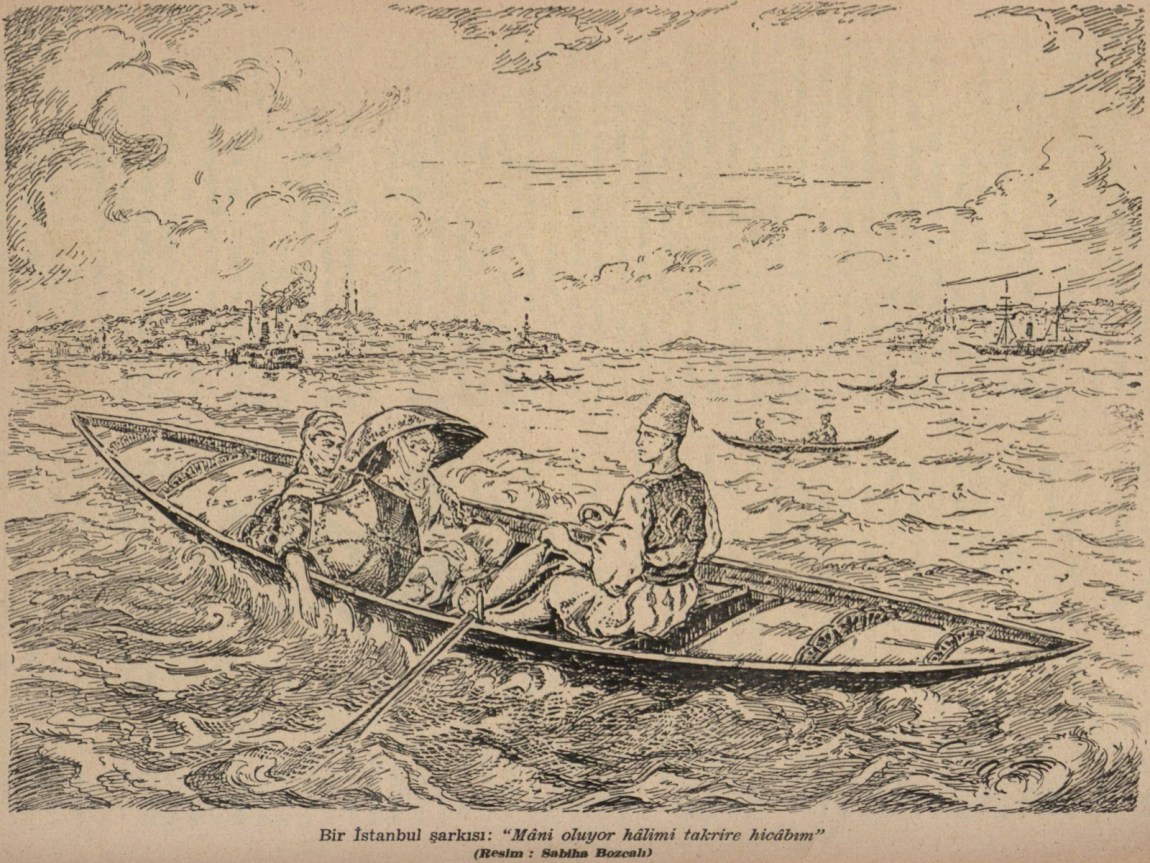

Koçu called members of his writing and editing team his “pen pals.” Instead of using photographs, they commissioned artists to illustrate the articles. The design team, responsible for portraits, maps, sketches, and city plans, comprised ten artists, including Sabiha Rüştü Bozcalı, Turkey’s first female illustrator, who produced more than nine hundred illustrations for the encyclopedia. Koçu issued the first monthly fascicle in a print run of three thousand copies.

Located on Istanbul’s Ankara Street, in the bustling, touristic, ancient neighborhood of Sirkeci on the Historical Peninsula, the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi bureau soon became a meeting place for hacks, editors, poets, historians, and anyone who savored gossip about Istanbul’s notable locals or visitors. There stories could be heard about, for example, Adel Akşiote, a Jewish boxing manager who fell in love with the sport at a young age, couldn’t pursue it himself because of his frail body, but earned plaudits during World War II by inviting “American soldier-boxers to Istanbul” for fights; or about Hans Fischer, a young “hippie tourist” from Germany who first visited Istanbul as a teenager in the company of a Turkish merchant, lived with him “for a month in a hotel in Sirkeci,” and left when the older man asked him to get circumcised and stay in the country. In 1968 he came back with “a girlfriend named Erta.”

After work the staff would go to a small restaurant near the Eminönü waterfront to treat themselves to rakı, the Turkish national drink made of twice-distilled grapes, and fish freshly caught from the Bosphorus Strait. From the nearby ferry terminal Koçu would cross the strait to Göztepe, a residential neighborhood, and walk to the wooden mansion he had inherited from his father, a school administrator who contributed articles to history magazines.

When the staff published the sixteenth fascicle in 1949, Koçu lost his patron’s support and had to self-finance the encyclopedia. Pitching his project as “a drop of water” in the desert of Turkey’s cultural life, he invited potential funders to visit the office and witness the writing and editing of the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi with their own eyes. But on the back cover of the thirtieth fascicle, his tone changed:

Rather than trying to teach me and show the way by asking, “Why doesn’t the Municipality buy it? Why doesn’t the Ministry of Education help? Why doesn’t the Party get involved?” open your purses once a whole year, for İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, and pay the subscription fee of 1,560 kuruş, the price three people spend on alcohol during a night out.

He announced subscribers’ names on the covers of the next fascicles, yet these efforts came to nothing. Financial difficulties forced publication to halt in 1951 at the thirty-fourth fascicle. By this point three volumes of the encyclopedia had been published, seven years had passed since the launch, and the team had only reached “Bahadır Street.”

A businessman involved in ironworks funded the encyclopedia’s second era, and in July 1958 the team resumed publication. The contributors, a mix of professors, amateur historians and journalists, included the founding father of Turkish folkloristics, Pertev Nailî Boratav, and the historical preservationist Çelik Gülersoy. Koçu remained responsible for around 85 percent of all the articles, some of which he also illustrated under a pseudonym. The team devoted three years to revising and republishing the first three volumes. Each of the second era’s fascicles were sixteen pages long and about eight by twelve inches. None of the contributors were paid for their work. Instead Koçu treated them at Pandeli, the legendary Sirkeci restaurant.

Production took so long that older contributors who had worked during the first era began to die. In 1965 Koçu again lost his benefactor’s support, and transferred his documents to his house in Göztepe. In the last decade of his life he treated the encyclopedia as his fiefdom, subjecting contributions to severe editing sessions, rejecting some outright, and growing increasingly anxious that his project might be unfinished when he died. Because of the editorial chaos, the pace of production slowed from 106 fascicles between 1958 and 1965 to 67 between 1965 and 1974, when the İstanbul Ansiklopedisi stopped publication again, this time in the 173rd fascicle.

In his last days Koçu sank into depression. He learned that people were repurposing his volumes as chair cushions; his former publisher was pulping the copies stocked in his depot. Despairing that his decades-long project had fallen into total obscurity, he issued an ultimatum. “I plan to bring journalists, scholars, publishers, my friends, and those claiming to be my friends to my home,” he reportedly told an acquaintance, months before his death.

I’ll show them the rest of the encyclopedia, ready from A to Z. I’ll present each article individually. Then I’ll call porters, and they’ll bring all these documents, photographs, pictures, and plans to the garden. There I’ll strike a match and burn them all.

Fortunately he never carried out this threat. After Koçu’s death on July 6, 1975, his archive was transferred to the offices of Tercüman. When that newspaper folded in the 1990s, the archive disappeared for years, becoming a mythic ruin, much like the ones to which Koçu devoted his life.

*

In the first years of the twenty-first century Turkish scholars became enamored with microhistory, after historians with doctorates from western universities began to teach at Turkish institutions and the History Foundation (Tarih Vakfı), established in 1991, organized a flurry of symposiums, exhibitions, and conferences. This new generation of historians published articles and monographs on the daily lives and politics of previously ignored figures from Turkey’s past, from Ottoman feminists to union organizers. The growing interest in such microstudies helped Koçu’s encyclopedia make a comeback in intellectual circles. Murat Bardakçı, a historian who wrote a weekly newspaper column about Istanbul, received a call from Koçu’s family members offering to sell him, for $80,000, the material they owned so that he could publish drafts of the encyclopedia’s unfinished entries.

When he met the family in 2003, Bardakçı learned that around seventy boxes of material collected for the unpublished parts of the project had been kept at a depot for years: approximately 40,000 items, including 1,460 volumes from Koçu’s personal library. In 2010 city officials from the Istanbul municipality announced that they would republish the encyclopedia along with the new material, but scholars presumably struggled to comb through all the notes, pictures, newspaper clippings, and lists. In 2018 Kadir Has University acquired the boxes, and it has been collaborating with Salt, a cultural nonprofit, to curate and categorize them. The result of their work, a website where visitors can pore through the complete archives, will launch later this year.

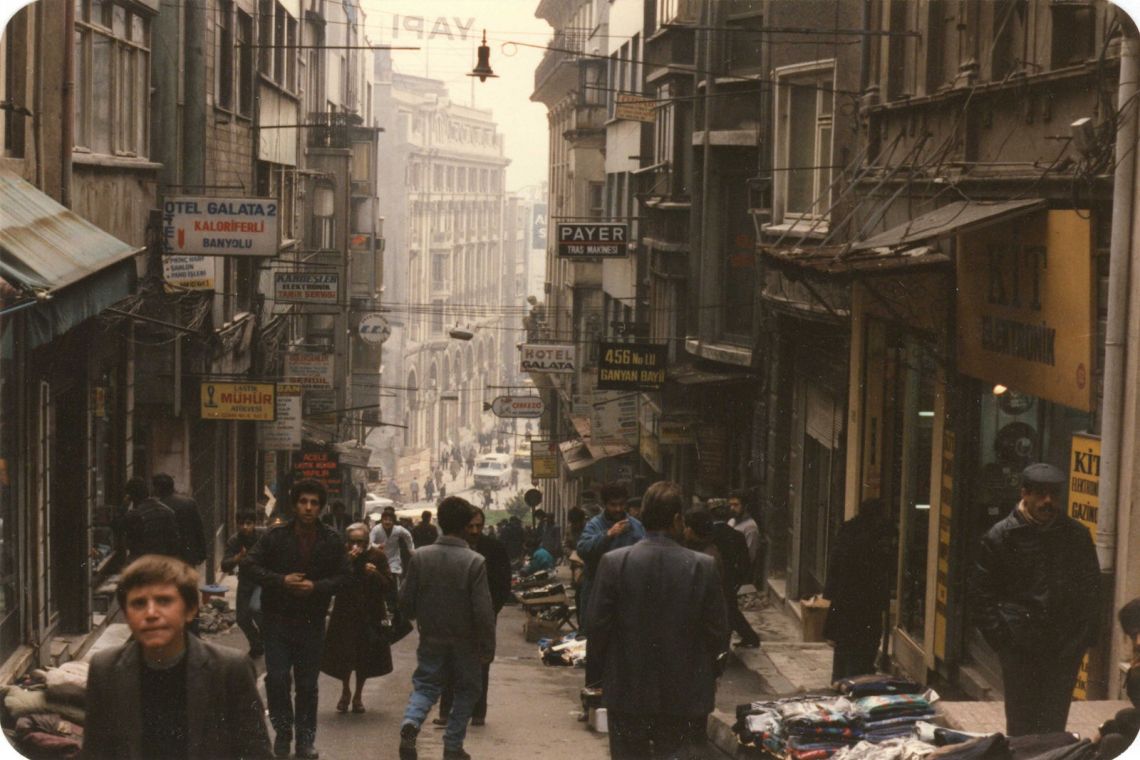

“No Further Records” includes some of Koçu’s material on Galata, where the gallery is located. Formerly a trading port, the neighborhood once served merchants, ship personnel, and porters alongside male sex workers and unemployed youth. Nearby were the Taksim Military Barracks, which reinforced the area’s reputation as a space for adventurous single men. The article drafts on display focus exclusively on the neighborhood’s downtrodden, displaced, and dispossessed. “Hasan Bey, Pazarola,” for example,

became a celebrity during World War I, the dark days of the Istanbul invasion, and the first few years of the Republic; this freak of a man was considered a good luck charm by the general public. He was fifty-nine inches tall with a scrawny body and a huge head; Hasan Bey’s underdeveloped intelligence meant that he lived with the naïveté of a child.

Another draft sketches a biography of “Gül, Bedriye,” a

beautiful eighteen-year-old girl whose name was mentioned in the municipality police news in the Istanbul newspaper in May 1970, known as Erkek [Tomboy] Bedriye in her neighborhood, Gaziosmanpasa. She has been walking around in men’s clothing since she was fourteen; she wears her hair like a boy.

In 1940 the Taksim Military Barracks were demolished under republican rule. It was Erdoğan’s determination to rebuild them that inspired the Gezi Park protests in 2013, when thousands of protesters occupied the space demanding a halt to the development. What would Koçu have thought of that attempt to preserve Istanbul against contemporary forces of destruction? He wrote conservatively about collectives and crowds, describing them as threats to Ottoman order and stability. Yet he also praised the beauty and singularity of individual rebels. If there is a political commitment hidden in the pages of his idiosyncratic encyclopedia, it is that Istanbul is a city made of myths, sure to stay open to transformation as long as its locals struggle, as they did at Gezi Park, to make it match their visions.