In 1956 the American artist Ed Clark grabbed a push broom and started sweeping his large canvases, stretched out on his studio floor, with paint. This was new. Even in a period of radical experimentation with the rudiments of painting it is hard to think of an artist who wielded a new implement with such vigor and verve. And for such duration: Clark pushed the broom consistently over the next six decades, finding it quite useful, as a show of his work this fall at Hauser & Wirth in New York makes clear. Near the end of his life he was adamant that he had made a stride in the history of his medium. “There’s no evidence of anybody using the broom but me,” he told the artist Jack Whitten. “Go dig it up in a museum. I’ll be the only one with a broom.”

By his own account the broom gave Clark not width, solidity, or distance, but speed. “That’s modern times,” he said. Take Locomotion (1963), a painting with a title that gives a sense of his winsome propulsion. Great streaks of green, orange, blue, and white crash into globs of pink and yellow and other shades of orange, as well as the edges of the canvas. It is difficult, especially in the lower-left quadrant, to tell just where the push broom has been applied and at what point in the compositional process. The effect is a fine balance between extemporaneity and precision, freedom and intention. Here and in most of the fourteen paintings at Hauser & Wirth, the broom allows Clark to call attention to the surface of the canvas and its boundaries. So did his ingenious and original shaped canvases, though only two of them—the circular Untitled (Vétheuil) (1968) and the oval Untitled (circa 1970), both riffs on color-field painting, which ruled the day—are on view. The limits of a painting, and of painting, mattered a great deal to him.

Clark was born in New Orleans in 1926. His mother was a seamstress who worked in a factory and did odd jobs at home, and his father was a gambler without a steady income. After moving to Baton Rouge the family joined the millions of black Americans who fled the South during the Great Migration. They landed in Chicago. Clark’s first commissions, he recalled in 1997 to the poet Quincy Troupe, were at Catholic school, where “they needed pictures”: angels on the blackboard, Easter cards, the Madonna. “That gave me a kind of confidence,” he said.

During World War II Clark joined the air force and was stationed in Guam. When he returned to Chicago he enrolled at the Art Institute, where he received a classical training on which he drew even at the height of his abstract work. “You took drawing before you took painting,” he told Troupe. “You took still life painting before you took figure painting…. I took only what was pertinent to art making, and I really knew that was all I wanted to do.” Like many black American artists of his generation, after art school Clark left for Paris. There he found a culture that made him “see something racially.” He learned from the painter Larry Calcagno upon his arrival in 1952 that the French government had planned a major museum show of contemporary American artists, then canceled it, having found youngsters from Ellsworth Kelly to Beauford Delaney wanting. “Over there, rejection had nothing to do with being black,” Clark said. “I was viewed as American. It wasn’t about race.”

In his book 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (2016), an excerpt of which appears in the Hauser & Wirth catalog, the art historian Darby English writes that when Clark finally started getting attention near the end of the twentieth century, critics tended to “fix on the idea of the artist’s mystical transmission of black culture into his paintings.” In the catalog of Quiet as It’s Kept, the 2002 show in Vienna in which David Hammons brought Clark’s work together with that of the painters Stanley Whitney and Denyse Thomasos, one critic proposed that Clark’s broom was a symbol of “the kind of labor available to African-Americans…arriving from the [South] to the cities.” English argues that such a representational reading of Clark’s work “annexes [his] practice to Black Art and tries to overwhelm its abstraction.” Clark’s paintings, he insists, ask “to be seen in a different light.”

*

“You are obviously a painter,” Clark remembers learning from his teacher the sculptor Ossip Zadkine. “You don’t think in the round.” No surprise, then, that his first and predominant influence was Cézanne, whose work he first saw not on a museum wall but printed in Holiday magazine. “I could see that there was something there,” he said. “He was pulling things around, respecting the flat surface of the canvas.”

Advertisement

That Cézanne revolutionized the way artists approach the canvas is a position taken by innumerable abstract painters and elucidated in a recent book by the British art historian T. J. Clark. In If These Apples Should Fall, Clark writes of Cézanne’s “miraculous…clumsy adherence to two dimensions” in landscapes like Pool at Jas de Bouffan (circa 1876–1878), with its sky “flapping in front of us like half-finished canvas.”1 In that painting, Clark writes, “space peels away from the totality of time, light and atmospherics, and starts to become a thing in itself.” The description suits just as well Clark’s Untitled (Vétheuil): a radiant sky blue in the top third of the canvas and, beneath it, a pink fading into a purple-gray would-be horizon line create the impression—though, crucially, not the actual form—of a setting sun. The essence of landscape, the genre in which Cézanne made his breakthrough by melding foreground and background, hovers over most works in the show, all the way through Homage to the Sands of Springtime (2009).

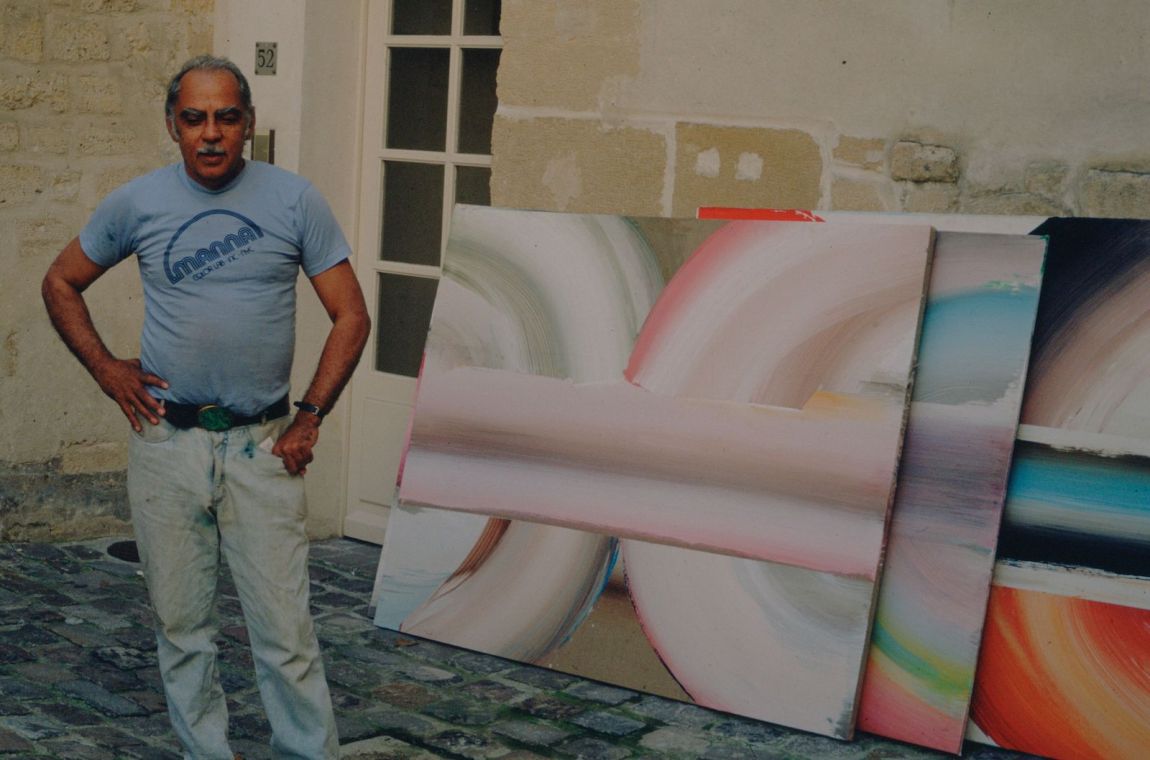

In France Clark also saw the paintings of Nicolas de Stäel, a Russian-born French abstractionist. Clark was too bashful to introduce himself the year he got to Paris, but his encounter with one of the older artist’s football field paintings, in which Clark observed that the field comes “right up onto the plane,” spurred him to abandon, at twenty-six, the representation and depth of his schooldays: “I’d never seen a painting with these big strokes.” He barreled toward a high modernism whose very subjects were canvas, broom, wooden support, oil, and acrylic. Clark reached a peak in the Eighties, when he pulled out all the compositional stops with quick, deliberate push-broom semicircles. In North Light (Paris) (1987) and Red, Blue, & Black (Paris Series #4) (1989), they dance across the canvas, though we’re watching the dancers from above.

“Where has Edward Clark been all our lives?” asked the critic Cynthia Nadelman in 1980, on the occasion of his retrospective at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The question rings half a century later with more regret than revelation. A show at one of the world’s glitziest galleries is something—“long overdue,” I ought to say—but there is such a thing as too little, too late: modernism has its canon, and Clark died in 2019. If any aspect of his work manages to shine well into the future, it will be his method. Getting back to basics, all one’s painting life, in order to push one’s art and one’s medium forward: it is a way of working that looks impossibly fresh under the good Hauser & Wirth skylight.