The first land in Europe to abolish capital punishment was Tuscany, where Grand Duke Peter Leopold ended the practice in 1786. When he left Florence in 1790 to become Habsburg Emperor Leopold II, Mozart wrote a coronation opera for him, La clemenza di Tito (1791), celebrating the Roman Emperor Titus for his clemency; the plot turns on Titus’s decision to pardon the man who had sought to assassinate him. Capital punishment can be found everywhere in the operatic repertory, as it provides dramatic vocal opportunities to wring emotion from the imminence of death. In Verdi’s Aida (1871), after a scene of judgment, the tenor is condemned to be entombed alive and the soprano dies, singing, along with him. Verdi’s Don Carlos (1867) takes a different perspective—capital punishment as public spectacle—in its scene of the Spanish Inquisition burning heretics, while in Puccini’s Turandot (1924) the eponymous Chinese princess presides over the systematic execution of her suitors, with death as the penalty for failing to answer the riddles she poses. (One foreign prince is beheaded during the first act.) Two of the greatest modernist operas of the mid-twentieth century concern capital punishment: Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites (1957), in which a cohort of nuns goes to martyrdom at the guillotine in the French Revolution, and Britten’s Billy Budd (1951), which culminates with Billy’s shipboard trial, sentencing, and execution.

Unlike the nuns in Dialogues of the Carmelites or Puccini’s Suor Angelica (1918), Sister Helen Prejean, the conflicted nun at the center of Jake Heggie’s contemporary American opera Dead Man Walking, never wears a habit. Vatican II, the reforming Catholic council of the 1960s, removed the obligation to wear black habits and encouraged nuns like Sister Helen to leave the convent and dedicate themselves to social missions, though it failed to give them the spiritual prerogatives that would have made them equal counterparts to male priests. In Heggie’s opera—adapted from Prejean’s 1993 memoir and set to a libretto by the late Terrence McNally—Sister Helen wears a dowdy gray dress as she drives along the highway to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, where she will soon become the spiritual adviser for a convicted rapist and murderer on death row.

The star of the Metropolitan Opera’s new production is the marvelous Kansas City mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato. Singing to herself as she drives, accompanied by gentle woodwinds, Sister Helen recalls becoming a nun and trying to explain her decision to her puzzled family. Heggie gives her a lyrical musical idiom of American reminiscence that recalls the spirit of Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville” cantata. DiDonato is comfortably colloquial as she soliloquizes, her aria interrupted by a lovely little duet with the motorcycle cop who pulls her over for speeding and then sends her on her way, asking her to say a prayer for his mother. As she gets closer to the penitentiary she sings with growing fervor: “This journey to Christ. This journey to my God. This journey to myself.”

*

The Met has always been a home for European opera—its first season opened in 1883 with Charles Gounod’s Faust, composed in French, sung in New York in Italian, and starring the Swedish soprano Christina Nilsson—but until recently the annual opening night of the fall season very rarely showcased an American work. In 2019, however, the season opened with George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Two years later the gala selection was Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, and last week, after two decades of traveling around the world, Dead Man Walking finally arrived at the Met to open the 2023–2024 season.

Dead Man Walking was Heggie’s first opera, written for the San Francisco Opera in 2000, and he has since maintained a commitment to American meditations and mythology on the operatic stage, with an ambitious, almost all-male opera based on Moby Dick in 2010 and a comic opera based on It’s a Wonderful Life, complete with a soaring soprano angel, in 2016. In Dead Man Walking Heggie was already very much a singer’s composer, setting text to be clearly enunciated and readily understood over the orchestra’s carefully controlled textures, his rich lyrical and melodic talent on display. DiDonato begins the opera with an a cappella hymn, “He Will Gather Us Around.” She is joined by a children’s chorus—its members literally gather around her—and by her fellow nun Sister Rose, sung by the soprano Latonia Moore, who claims the glorious top notes while DiDonato harmonizes from below. DiDonato, who has been especially acclaimed at the Met in Rossini roles, was very convincing last season as Virginia Woolf in The Hours, singing with beautiful solemnity. Moore, a notable Aida at the Met, was at the center of the company’s productions of Fire Shut Up in My Bones and Blanchard’s earlier opera Champion, creating memorable vocal characterizations of two notably different African American mothers.

Advertisement

During the orchestral prelude of Dead Man Walking the audience watches a brutal double murder on video, and early in the first act DiDonato and Moore trade lines in a conversational duet that outlines the premise: the killer has been corresponding with Sister Helen from death row, and now he wants to meet her. Sister Rose pushes the music forward with the pulsing phrase “He’s a cold-blooded murderer,” which Helen answers with a lovely musical line: “But we’re all of us God’s children.” Later they will harmonize in perhaps the opera’s most exquisite piece of music, a second act duet on the theme of forgiveness.

When the events dramatized in Dead Man Walking took place, in the early 1980s, American law had recently passed through a period of uncertainty over the death penalty. The Supreme Court suspended capital punishment for its seeming arbitrariness of application in 1972 only to approve it again four years later, declining to forbid it as “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eighth Amendment. In the 1990s Pope John Paul II was a forceful opponent of capital punishment from the Roman Catholic perspective, and five years ago Pope Francis amended the Roman Catholic catechism to explicitly condemn it. Prejean wrote her memoir in this spirit of principled Catholic opposition: “Jesus Christ, whose way of life I try to follow, refused to meet hate with hate and violence with violence.”

On the road Sister Helen hesitantly tries to imagine the prisoner she is going to meet. She prettily arpeggiates the five syllables of his Cajun name—Joseph De Rocher—in a rising and falling arc, which she echoes with the five numbers of his prison identity, 9-5-2-8-1. (The name is fictional: De Rocher is a synthesis of two murderers who figured in the memoir.) His presence onstage calls for music with a more feverish pulse, though he too finds a more lyrical vein as he asks his visitor, “You ever been with a man?” She completes the musical line with her unabashed reply, “If you mean physically intimate, no.” The Californian bass-baritone Ryan McKinny interprets De Rocher as a man of shifting moods: snarling, nostalgic, defiant, demanding, needy.

The great challenge of the opera as conceived by Heggie and McNally, and as executed by DiDonato and McKinny under the direction of Ivo van Hove, is to make plausible that these two characters are drawn to each other in ways they themselves do not quite understand. McNally, who died of Covid in 2020, was one of the major American dramatists of the last half century, and particularly noted for plays about opera like The Lisbon Traviata and Master Class. His libretto allows for ambiguities of motivation that leave a powerful part of the characterization to the music. At one point Sister Helen asks De Rocher in conventional psychological language to “let me in.” “Have you let me in, Sister Helen?” he asks. “Oh yes,” she sings, “so much more than I ever imagined.” McNally’s plain phrasing allows Heggie to launch the musical line in a more extreme spirit of ecstasy that suggests some euphoric affinity between Sister Helen and Saint Teresa of Avila, the sixteenth-century nun who wrote about her mystical religious transports.

*

Last season Van Hove directed the Met’s new production of Don Giovanni, another opera about a rapist and murderer, but Mozart gave his protagonist such musical charisma that it becomes the director’s job to signal the sociopath behind the seducer. In Dead Man Walking the opera works the other way around: only gradually does it allow the sociopath to evoke some sympathy. In the memoir’s 1995 film adaptation, Susan Sarandon’s determined encounter with Sean Penn felt like a sort of duel; here the relationship more often takes the form of a duet. In the second act the nun and the convict bond over their common love for Elvis Presley, trading lines in rock rhythms. “You wouldn’t be human if you weren’t scared,” she sings immediately afterwards:

De Rocher: Human? Who said I was human?

Sister Helen: I think you’re very human.

DiDonato gives a moving performance of a woman unsure of herself, sometimes with a self-deprecating sense of humor, full of trepidation about where she is heading on this journey to her God. The flutes are her constant companions, as if to sustain her spirits, and she sometimes receives velvety consolation from the bass clarinet. By the end of the first act Sister Helen finds herself in a complex ensemble, dramatically and vocally struggling to hold her own against the reproaches of the four parents of the two murder victims. The parents, appalled that she seems to be defending the murderer, construct a powerful quartet based on a simple three-note descending motif for the repeated reproach “You don’t know”—but then that same three-note motif becomes the musical setting for their remembered last words to the children on the night of the murder, the banal trisyllabic comments that turned out to be a final leave-taking: “Comb your hair/Clean your room.”

Advertisement

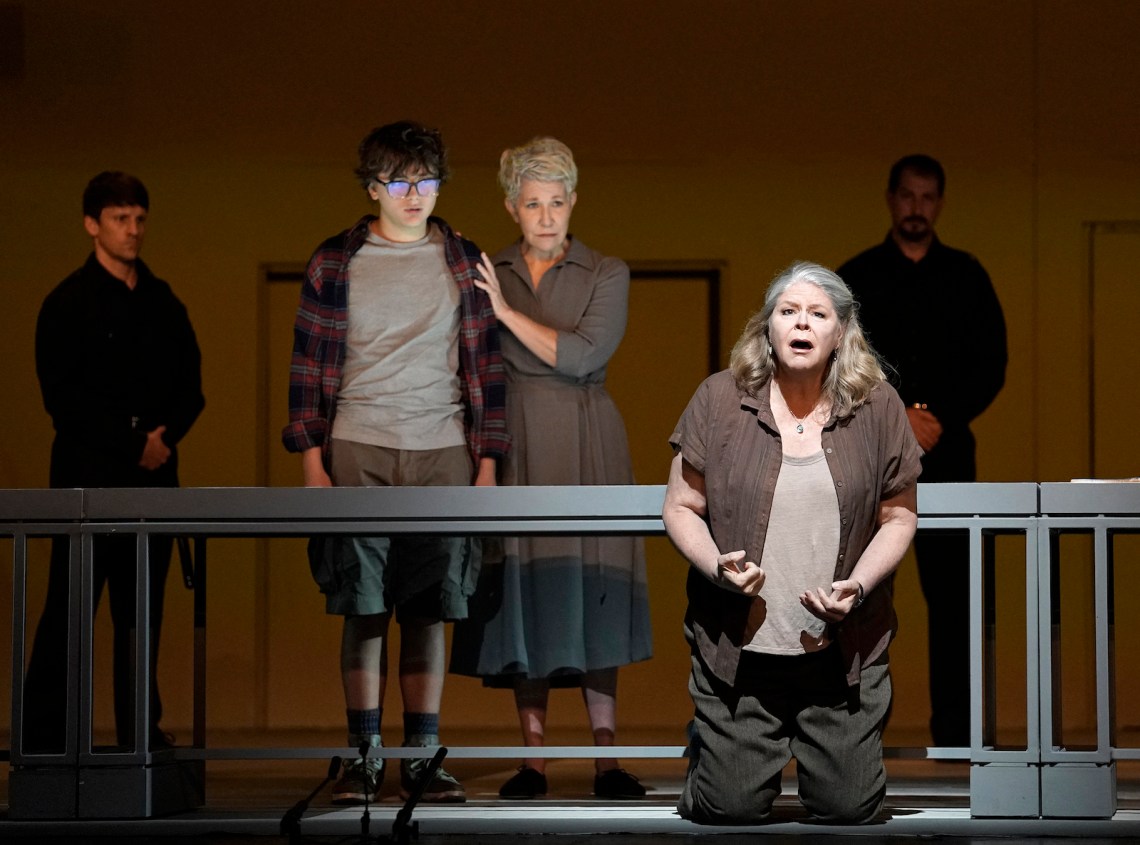

Sister Helen tries to interject her sympathy, her pleading, but the quartet rejects her advances. She does, however, forge a bond of solidarity with De Rocher’s mother, a role taken here by Susan Graham, who was the original Sister Helen when the opera was first produced in San Francisco. McNally gives the grieving mother the libretto’s simplest phrases, and Heggie composes a musical line for her so fragile that at moments it collapses altogether, giving way to mere speech, as when she turns to Sister Helen, just before the execution, and asks her to take a family photograph. Graham’s final outbursts lie somewhere between operatic lamentation and mourner’s keening.

The crescendo of the orchestra sometimes swells a little too predictably and cinematically as dramatic tension builds within a scene, but on the podium the Met’s music director, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, skillfully kept the dynamics in check, brought out the score’s lyrical beauties, and found subtleties in the coloring. The designer Jan Versweyveld presents a geometrically rectilinear set of doors and windows, everything at right angles, with a square of light forming the central staging space and a sinister dark box overhead, which also serves as a video screen. The dark box and the square of light define the prison’s restrictions and oppressions: Van Hove and Versweyveld dispense with bars and barbed wire, and De Rocher is never seen wearing handcuffs.

Dead Man Walking might leave you uncertain, by the time you get to the final ensemble, of whether this is really an opera that makes a case against capital punishment. At its musical and dramatic climax—the staging of the execution—it seems instead to offer a sort of catharsis. By the time De Rocher’s final moment arrives, Sister Helen is singing rapturously to him: “I will be the face of Christ for you. I will be the face of love for you.” The chaplain begins to recite the Lord’s Prayer, the orchestra offers a funeral march, and a liturgical chorus of guards and prisoners and nuns gradually joins and swells, crescendo: “Thy Kingdom come.” De Rocher asks for forgiveness from the parents of his victims, Sister Helen having promised him, in a gospel melody, that the truth will set him free. The nun and the murderer declare that they love each other, and the lethal injection is administered on an almost cruciform gurney.

But Van Hove also goes some way toward subverting this cathartic climax. The execution itself is a theatrical event, a public spectacle, with sitting members of the chorus watching from the sidelines as a graphic video of the injection plays overhead. The opening night audience, in their gowns and tuxes, became the uncomfortable spectators on the other side of the proscenium arch. (That public included Sister Helen Prejean herself, watching her operatic incarnation.) In Suor Angelica Puccini’s agonized nun poisons herself at the end of the opera, and in Dialogues of the Carmelites the nuns of the ancien regime go to the guillotine while singing the Salve Regina. In Dead Man Walking the modern nun’s tragedy is surviving and bearing witness. With the execution carried out, Sister Helen is left alone and bereft in the spotlight, singing her gospel hymn, a cappella: “He will gather us around.”