It seems to be impossible to tell a story about Judee Sill without resorting to overused tropes and cliche. The Los Angeles musician and composer completed two exquisite albums in the early 1970s in what she called her “country-cult-baroque” style, filled with “licks of Pentecostal fury,” but her critics, documentarians, and fans alike often reduce her to the sensational or scandalous: a 1963 arrest at age eighteen for armed robberies of liquor stores and gas stations to fund a drug habit, or reminiscences from old flames about her sexual adventurousness. Sill died of an overdose in 1979 at thirty-five, and loss tends to be the theme of most retrospective efforts to publicize her music. The New York Times gave her an obituary in 2020 as part of its series about “remarkable people whose deaths…went unreported.”

A year later, Rolling Stone published perhaps the most comprehensive account of her life to date, including interviews with friends and collaborators such as Graham Nash, J. D. Souther, and Linda Ronstadt, along with insight from Sill’s surviving relative, her niece, Donna Disparti. The profile ably accounted for the career of a woman in the music business who didn’t parlay sex to sell her songs—an important distinction in light of the fact that she did actually sell sex prior to getting a recording contract. But it also makes a bizarrely off-color claim that her favorite way to be photographed was with a lollipop in her mouth—hardly consistent with the surviving images of her—and focuses on the conflicts that arose in packaging an artist who had enormous talent but little to no interest in meeting audiences where they were.

Beyond what Sill said about her own life, which the friends and industry people who survive her don’t dispute, there’s little factual information to go on. The Times and Washington Post don’t even agree on whether she was born in Oakland or Studio City, California. It’s perhaps inevitable that she has been filtered through others’ memories of her, coloring how new audiences will receive her work, but these portrayals of Sill suggest how many unconscious biases linger in attempts, even by purported allies, to reconstruct the lives of ever-overlooked female artists.

The Rolling Stone profile concluded with some advance promotion for a documentary, Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill, which premiered late last year at DocNYC. It quotes one of the film’s directors, Andy Brown: “Judee’s life and her lyrics are very intertwined…. You can’t separate them, and that’s what makes [her music] so timeless and powerful. I think people learning more about her will see that struggle and connect it to her music.” His film—codirected with Brian Lindstrom—marshals biographical material to support an argument that her work was intimately linked to her personal experience.

I have to wonder if he and I even heard the same songs. Here’s an excerpt from “The Lamb Ran Away with the Crown,” from her 1971 self-titled debut LP:

Once I heard a serpent remark,

“If you try to evoke the spark,

You can fly through the dark,

With a midnight raven,

To rule the battleground,”

So I drew my sword and got ready,

But the lamb ran away with the crown.

It could be allegory, yes, but I’d hardly call this “confessional” songwriting, as practiced by artists like Tori Amos or Elliott Smith and as epitomized now by the mass identification frenzy around Taylor Swift’s theater of the self or Phoebe Bridgers’s relatable but banal ennui.

Lost Angel casts Judee Sill as the main character in a trauma plot while only weakly gesturing at the troubling yet essential mystery of faith, an unavoidable theme in her work. A significant part of the runtime is spent hearing the same perspectives from the same people interviewed in the Rolling Stone article, or in the 2014 BBC Radio documentary The Lost Genius of Judee Sill, which also availed itself of the insightful comments from Sill that appeared on Live in London: The BBC Recordings 1972–1973 (2007). Disparti appears early in Lost Angel to clarify what had previously been insinuated—that Sill was molested by her stepfather. The consistent inclusion of his name in her narrative—ironically, horrifically—allows him to loom undeservedly large. I’ll be leaving it out.

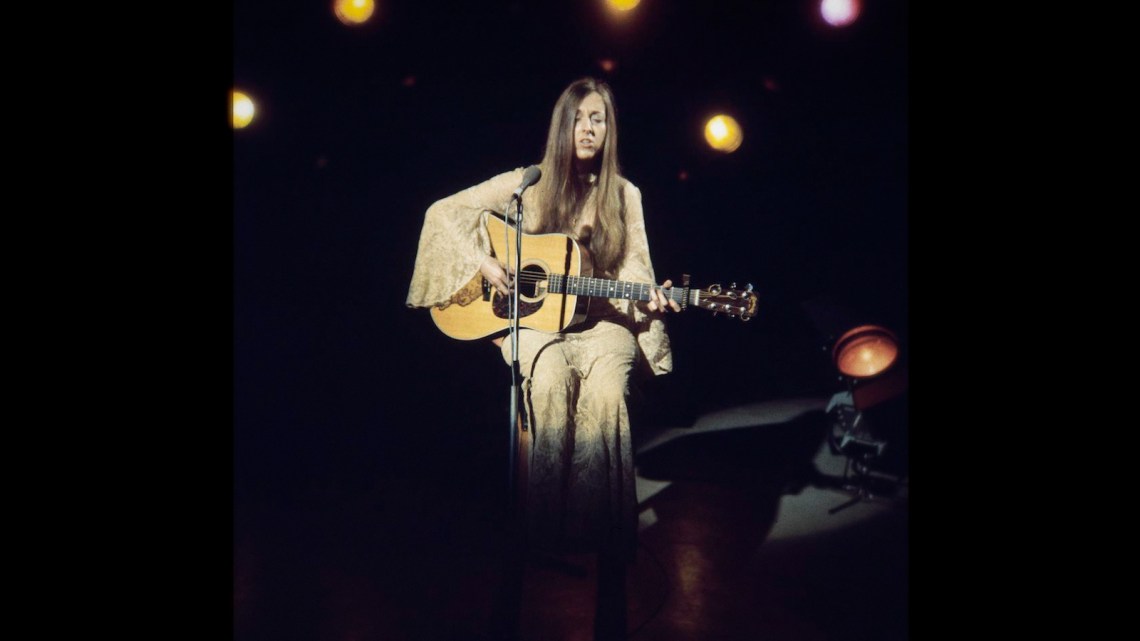

Judee Sill (1971) was originally released on David Geffen’s first record label, Asylum. She was twenty-seven, and had been the first artist he signed. When Geffen asked her how big she wanted to be, Sill replied, “How big can I be?” She spoke with disarming frankness and a correctly high estimation of her talents: “I told him I wanted to be a bigger star than has ever been before.” (Before she had even put a record out, she wrote, produced, and conducted strings for The Turtles’s recording of the song “Lady-O,” which charted in 1969.) The album was apparently produced in eight days and combines plucky guitar in varied tempos, earnest horns, and complex passages of multitracked harmonies. Lush string arrangements segue into rollicking, jazzy, piano-led jams. The lyrics are sung in her characteristic intonation, rapidly rising and falling on nearly every other word. The record is buoyant, totally assured, and straightforwardly appealing. You simply would not know from listening to it that Sill was a recovering heroin addict, and it would be hard to conceive of her as an abjectly tortured soul.

Advertisement

The narration in her lyrics tends to be idealized and oblique, as if she is reminding us of old tales long forgotten, and populated by ciphers like a “phantom cowboy” and “enchanted sky machines.” It’s hard to think of an album opener more nonchalant about setting the listener up for the extraordinary than “Crayon Angels,” in which she sings,

Crayon Angel songs are slightly out of tune

But I’m sure I’m not to blame.

Nothing’s happened but I think it will soon,

So I sit here waiting for God and a train,

To the Astral plane.

She lets us know she is waiting for greatness, even if she is, for now, channeling material without fully grasping its import herself.

Holy visions disappeared from my view,

But the angels come back and laugh in my dreams,

I wonder what it means.

*

Sill said she realized she could harmonize with herself on the piano when she was a child, in her father’s bar in Oakland, California. It’s a telling detail: she discovered her own talents as if by chance, or fate. She got serious about music around the age of twenty, when she learned to play church organ at a reform school in Ventura, where she apparently assisted the music and art teachers and served as the organist at the school’s requisite religious services. She later said she was deeply inspired during this time by Baroque music, particularly Bach.

No one from this period of Sill’s life appears in Lost Angel or on record as a source in earlier documentaries or articles. An article presumably describing her school’s program is seen on screen for a few seconds, with the obnoxious pull-quote, “A powder puff and lipstick can go a long way toward rehabilitation.” We never learn whether she had a mentor or was an autodidact. The documentary instead moves right along to her gigging around Hollywood in her mid-twenties, playing jazz bass as part of a trio at venues like the Troubadour or Artie Fatbuckers’ Cellar, and to the men (mostly) who can testify to her novel personality. Her friends reflect on her “darker nature” (Nash) and that she “didn’t play the [music industry] game very well” and was “terrible at kissing ass” (Souther).

A more useful observation comes from the classical music critic Tim Page—the author of a 2006 article in The Washington Post on the occasion of the first Rhino reissue of her records—who notes that her songs were built on top of the bass in a continuo, a distinct feature of Baroque composition. According to the Bach biographer Martin Geck, that style emerged alongside a new understanding of sacred music in which “beauty and harmony no longer serve merely to objectify and enhance a given text; they are now a vehicle for self-representation on the part of the faithful, who raise their voices to God—addressing Him passionately and directly.”

Sill claimed her music was inspired by Pythagorean tuning and that it came to her mathematically perfect from God: “It always comes out right, but I don’t really know what I’m doing.” But it remains unclear if she ever belonged to a particular church or organized religion. Ronstadt remembers that Sill had a certain enthusiasm for Rosicrucianism, an occult sect with historical roots in a Baroque-era movement. One of her later addresses, a house just off of Beverly Boulevard in central LA that’s now blurred on Google Maps, was blocks from a Rosicrucian lodge. Russ Giguere, from the pop band The Association, says of Sill, “She always thought that you could save someone—save their soul, through music.” We know she admired Nikos Kazantzakis’s historical novel The Last Temptation of Christ, first published in English in 1960, which famously portrayed Jesus as a man torn between a divine calling and an ordinary life. It’s tempting to consider Sill’s bohemian tendencies and devotion to music as something of a dynamic drama: a desire to go high could be both a worldly ambition and an all-encompassing intensity, maybe not unlike being high, or seeing one’s art as in service of a higher power.

Advertisement

In 1972 Sill introduced a track, “Down Where the Valleys Are Low,” at the Paris Theatre in London that was to appear the following year on her second album, Heart Food: “It’s about the place where romantic love and divine love meet and the holy fires begin to burn…. It’s kind of like a romantic gospel song.” She lamented in an interview with Bob Harris for the BBC that rock audiences “want to boogie on the lower levels, they don’t want to boogie on the higher levels.” Asked in an interview with Chris van Ness if her music was rock and roll, she responded point blank: “No.” Some terms she preferred were “occult, holy, Western, Baroque, Gospel.” One wonders if in addition to gospel she knew of female Christian mystics like the twelfth-century German composer, author, and abbess Hildegard von Bingen, or the thirteenth-century Middle Dutch poet Hadewijch. The latter, or a close follower, wrote:

You who want

knowledge,

seek the Oneness

within.There you

will find

the clear mirror

already waiting.

Compare those lines with “My Man on Love”:

In your eyes is an echo of

What once was passion, my friend.

If I cried out loud, could you hear these words,

Resurrection waits within

Sill wrote “The Donor,” the final track on Heart Food, in order to “musically induce God into giving us all a break.” She deploys the Kyrie eleison of Christian liturgy—a motif with origins in Greek pagan worship that means “Lord have mercy”—and harmonizes with herself in a multitracked cocoon of echoing vocals. It is haunting in its enclosure of the listener with Judee, whose message becomes distorted even as you hear her delivering it from all directions, accompanied by a piano gracefully doling out its repeated minor progressions. And then suddenly it all fades, capped by a piquant trill of the keys and a sparkling effect—the sound of someone bounding, passionately and directly, over our heads to something beyond.

*

The New York-based performance artist and filmmaker Jack Smith reflected near the end of his life that “lightness is one of the true eternal qualities that art essentially must possess.” In that 1988 essay, “Remarks on Art and the Theater,” he also observed that there was “an idealism in Baroque Art that is not in Modern Art. People are idealized. Events. Only that which is ideal is represented, in effect. The subjects in the seventeenth century had to be Biblical or mythological.” He could have been writing about “Jesus Was a Crossmaker,” Sill’s song that is obliquely about her relationship with another songwriter, J. D. Souther, but pivots between he—“a bandit and a heartbreaker”—and He. This proximity of romantic love and a religiously tinged fervor puts Sill’s music in the tradition of art like Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, the sculptural icon of the Baroque era that depicts the mystical experience of a female saint rendered as a sensuous encounter.

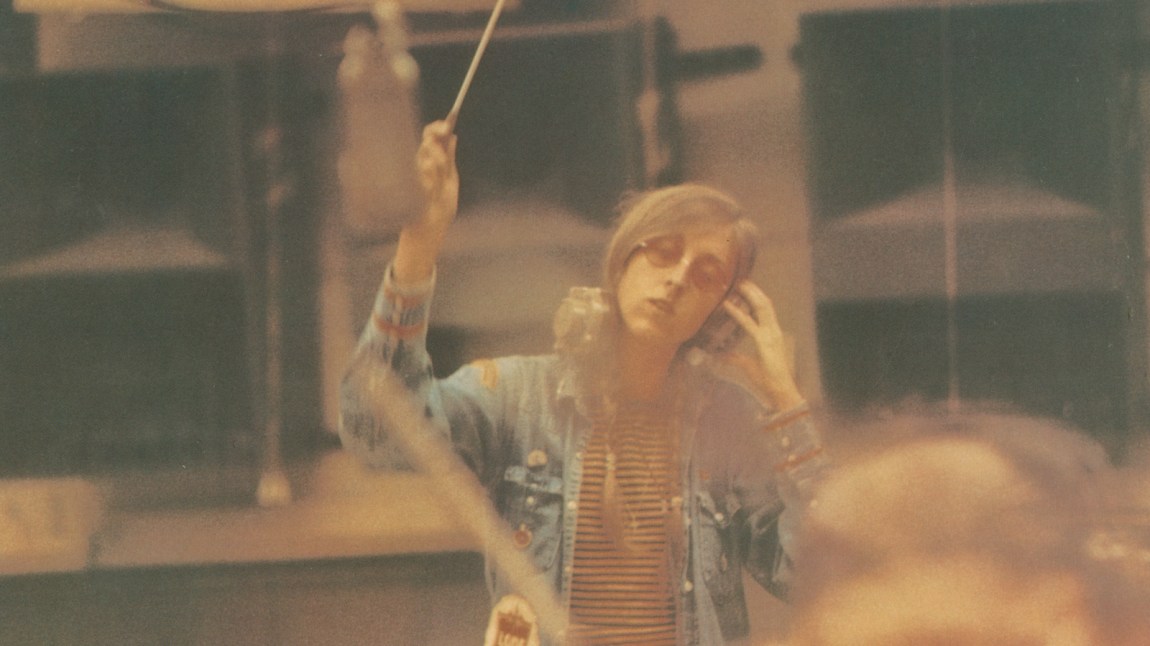

Though she was booked on tours with bands like Three Dog Night, her music has vanishingly little to do with rock at all. Even when she got through the door to her chance at stardom, her belief in herself and confidence in her vision—as well as her open rejection of anybody else’s rejection of that vision—hamstrung her. Promoters didn’t quite know what to do with steel guitar, loping cowpoke rhythms, and Bach progressions, and, as the promotion manager Ian Warner interviewed in Lost Angel admits, her record just fell through the cracks of his roster at Asylum. The jazz guitarist Art Johnson—who collaborated with her on some of her last songs, later released on the LP Dreams Come True in 2005—marvels that Sill conducted the strings section for her own record, as though there’s anything novel about a composer conducting. No one would speak about a man this way.

A somewhat defensive interview with David Geffen—a big get for the film, considering his absence from previous documentaries—seems diplomatically placed to dispel long-running rumors that he sabotaged Sill’s career after being her early champion. One piece of gossip that dogs her reputation is that she insulted him once while she was onstage, free-associating his homosexuality with his supposed predilection for pink shoes. (These alleged homophobic remarks aside, no one could really claim Judee Sill was all straight herself.) No one seems to have ever been able to quite substantiate this story, and the new film doesn’t clarify matters much. Geffen insists she received the same support as the rest of the artists he signed and summarily washes his hands of the matter: “There is no way to explain these things. The audience loves what the audience loves.” Her commercial failure, he seems to be implying, was inevitable.

And yet we might wonder if she stood much of a chance at a time when it was acceptable to publish reviews that began like this: “Judee Sill is one of those breed of American girls who’ve taken to singing who one supposes were previously engaged in quietly knitting at home and rocking gently back and forth on the chair in the porch.” The reviewer for the British rag Melody Maker must have neglected to look at the LP, which credits her with both writing and arrangements. She was scolded in the press for responding to her hecklers at concerts. Even Geffen, when pitched on the idea of getting Sill on tour with Billy Joel, passed, saying, “Who will come?” Being herself seems to have itself been a source of friction. So much for the wistful hyperbole of a more authentic time in the music industry.

Souther for his part seems to eventually get around to a more even-handed assessment of why she didn’t hit as hard as she had hoped: “How many people were interested in songs about a mystical Christ in 1972, ’73? Coming from someone with that very strange voice and strange combination of influences…. that’s not what was happening. Jackson Browne was happening.” Why it wasn’t possible in Los Angeles, of all places, to reroute her music toward a different goal—scoring for film, perhaps—is mysterious. In the documentary’s telling, after her label dropped her she had a swift, steep retreat into drugs and an abusive relationship. Injuries from a car accident in late 1973 aggravated matters further. In constant physical pain, she seemed to give up on any kind of career.

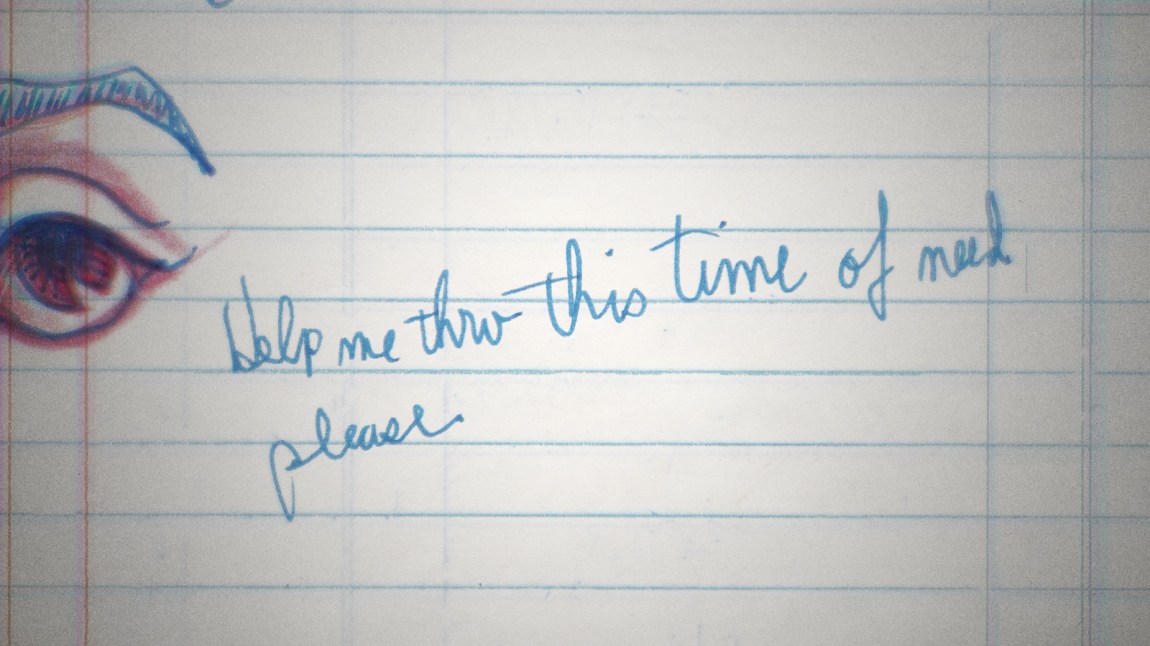

The last third of Lost Angel drags, with too many shots panning over her mediocre drawings and hammy animation sequences inspired by her desperately sad final diary entries. (“I TRIED TO ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES BUT I BROKE IN TWO.”) Lingering over this intimate material feels less compassionate and revelatory than gawping and violating. An immersion in her exquisite suffering is unhelpful for understanding her as an artist, but it fulfills her trauma plot. Audiences for whom Judee Sill is totally unknown will likely find this new documentary enlightening, whereas I’m confirmed in what I already know—she made perfect music, was not rewarded for it, and died more or less in ignominy. The consolation prize of rediscovery is that a new generation is given permission to flatter her in death as an “angel.”

We get a few glimpses of some of her musical transcriptions flitting past the screen, but too quickly to identify the song. Did she learn musical notation at the reform school, how, from whom? It remains unclear. Did her lyrics go through many versions, or were they also handed down in some spiritual transmission? Enough of Bach’s process has survived the centuries to afford scholarship, including a serendipitous discovery now and then, as when a transcript of a flute part from a cantata was fortuitously discovered in 1971—the year of Sill’s debut—sticking out of a pile of construction debris in New York.

The first thing said in the film might, ironically, be the only statement we need. It comes from the lead singer of Fleet Foxes, a band from whom I haven’t heard since Los Angeles Apparel was called American Apparel. “This is ‘The Kiss’ by Judee Sill. Judee Sill—an incredible Seventies songwriter, made two of the best albums ever, Judee Sill and Heart Food; hugely, hugely influential, and an incredible artist.” What else is there to know?