“It is a great relief to see a small work of art these days.” Elizabeth Bishop’s gallery note for a 1967 exhibition of Wesley Wehr’s miniature watercolors expresses not simply a preference for the small-scale but a feeling for how the small can disrupt one’s very concept of scale. Marianne Moore referred to Bishop’s debut collection, North & South, as a “small-large book,” and Bishop once confessed to reading “all of Dickens, volume by volume, with the strange ambition of writing, or rather finishing, one sonnet about him.” Ambition itself was a little strange to her, which is one reason she fought shy of it, or sought to translate it into something other than a mere plea for attention. As she added in her gallery note, “Why shouldn’t we, so generally addicted to the gigantic, at last have some small works of art . . . some intimate, low-voiced, and delicate things in our mostly huge and roaring, glaring world?”

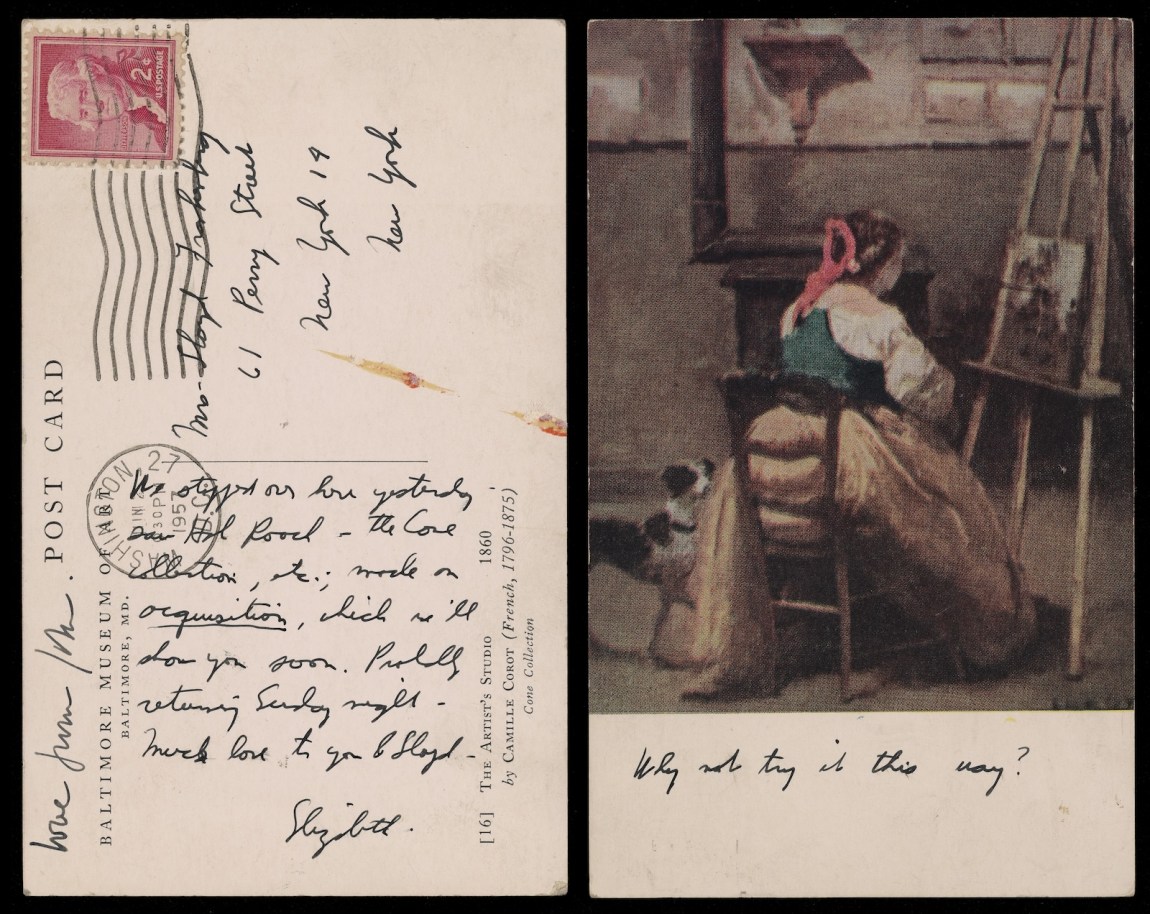

An exhibition at the poet’s alma mater, Vassar, asks this question afresh. “Elizabeth Bishop’s Postcards”—beautifully curated by Jonathan Ellis and Susan Rosenbaum—is itself a sonnet-like condensation: just one eighth of over five hundred postcards in the college’s collection have been selected. The show displays originals of the image side of the cards and facsimiles of the text side so viewers can see both sides simultaneously. Ellis and Rosenbaum’s superb introduction to the catalog (also available online) suggests that Bishop thought on and through these cards, and that they became “palimpsests of different literal and metaphorical points of view.” Indeed, she didn’t just send postcards; she collected, edited, and even made them. And as well as writing on the backs of the cards she sometimes doctored or annotated the images on the front. As early as 1936 she can be found playing around with gender roles as she dons boxing gloves to take on Louise Crane. Twenty years later, beneath a reproduction of Camille Corot’s The Artist’s Studio, she scribbles: “Why not try it this way?”

Unpublished postcards written by Elizabeth Bishop courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Vassar College Library

A postcard of Camille Corot’s The Artist’s Studio (1860) sent by Elizabeth Bishop to Lloyd Frankenberg and Loren MacIver, 1957

It was a question Bishop frequently asked herself. She asked it of other viewers, too, who may seek to find or recreate themselves through the very act of gazing. Ellis and Rosenbaum go so far as to assert that “the picture postcard is a synecdoche of Bishop’s aesthetics more generally.” The more you look, the more this rings true.

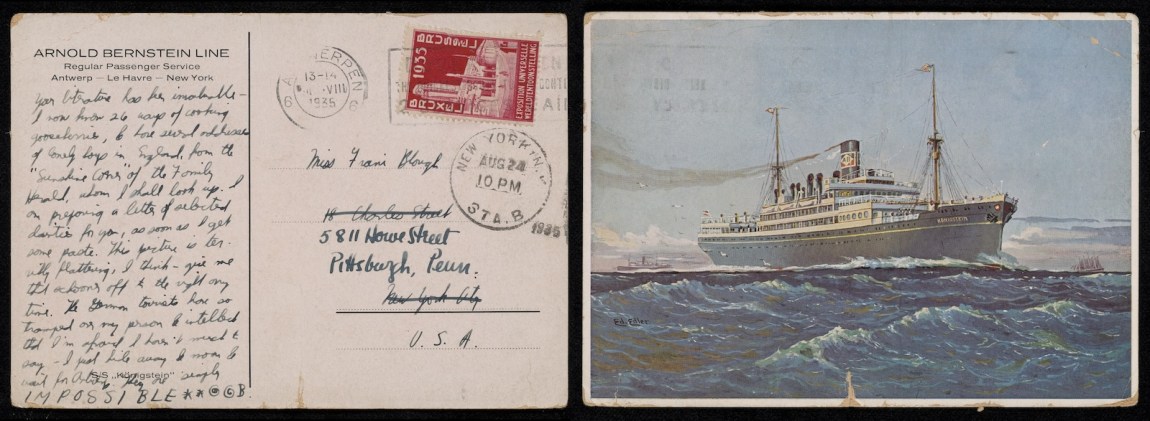

One of Bishop’s cards contains a telling aside—“if you’ll excuse my poetics”—which is perhaps her way of admitting that in this form she’s trying to get away with mischief. Postcards are associated with traveling, of course, and for Bishop questions of travel were incessant. Having grown up in both Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, after college she moved to New York City for a while and then traveled extensively in Europe and North Africa. She later lived in Key West, Pétropolis, San Francisco, Ouro Preto, and Cambridge, among other places. An early postcard in the exhibition, from August 1935, was written as she sailed to Europe. During the voyage she tells a friend that “I dreamt last night of paintings that wouldn’t stay still—the colors moved inside the frames, the objects moved up closer then further back, the whole thing changed from portrait to scenery and back again—keeping the same ‘lines’ all the time.” No picture ever really stays still for Bishop; she’s always reading it with multiple sightlines in mind, conjuring up various ways into and out of it.

Unpublished postcards written by Elizabeth Bishop courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Vassar College Library

A postcard of the SS Königstein sent by Elizabeth Bishop to Frani Blough Muser, August 24, 1935

“This picture is terribly flattering, I think,” she writes on the back of the postcard, which shows a large steamship in the foreground and a smaller boat off in the distance. “Give me that schooner off to the right any time.” The desire to swap the main event for marginal ephemera is characteristic, and it anticipates a comment she made nearly thirty years later in a letter to Anne Stevenson; certain dreams and works of art, she noted, “catch a peripheral vision of whatever it is one can never really see full-face but that seems enormously important.” Such a vision made her think of another seafarer—one who, like her, was in his mid-twenties when he first set sail:

Reading Darwin, one admires the beautiful solid case being built up out of his endless, heroic observations, almost unconscious or automatic—and then comes a sudden relaxation, a forgetful phrase, and one feels the strangeness of his undertaking, sees the lonely young man, his eyes fixed on facts and minute details, sinking or sliding giddily off into the unknown.

This is a portrait of the artist as a young woman, too, the one who was always en route.

Advertisement

*

Bishop’s postcards never really say “Wish you were here.” Or even when they do, something else is going on. In one postcard to Robert Lowell in 1968 she tells him that she has fallen and broken her wrist, and also a tooth, while on the front is a picture of Alcatraz, which she has captioned “Having a wonderful time . . . Wish you were here.” Another begins “Having a ? time. Wish you were here.” For Bishop, the “?” exists between what words might imply and what pictures might indicate.

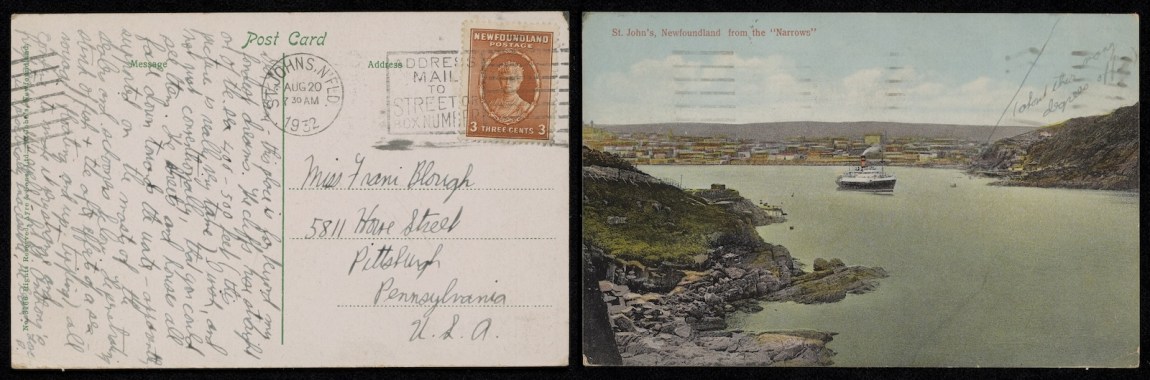

Another early postcard, sent to a friend from St. John’s in Newfoundland, shows a stretch of water with cliffs on each side. Of the latter, Bishop writes, “I wish, and not just conventionally, that you could see them.” She proceeds to annotate the photo (which she deems “very tame”) by penciling in her own sense of the cliffs’ gradient (“about this many degrees off”), adding that “The penetrating stink of fish + the after effects of a sea voyage floating and up-tipping, all combine to make it very strange and frightening (It’s swell).” That last word glints in the light—part seasick, part thrilled—like the mixture of tones whenever she casts her searching eye over coastlines in her poems. At the end of “The Bight,” for example, where “All the untidy activity continues,/awful but cheerful.”

Unpublished postcards written by Elizabeth Bishop courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Vassar College Library

A postcard of St. John’s, Newfoundland, sent by Elizabeth Bishop to Frani Blough Muser, August 20, 1932

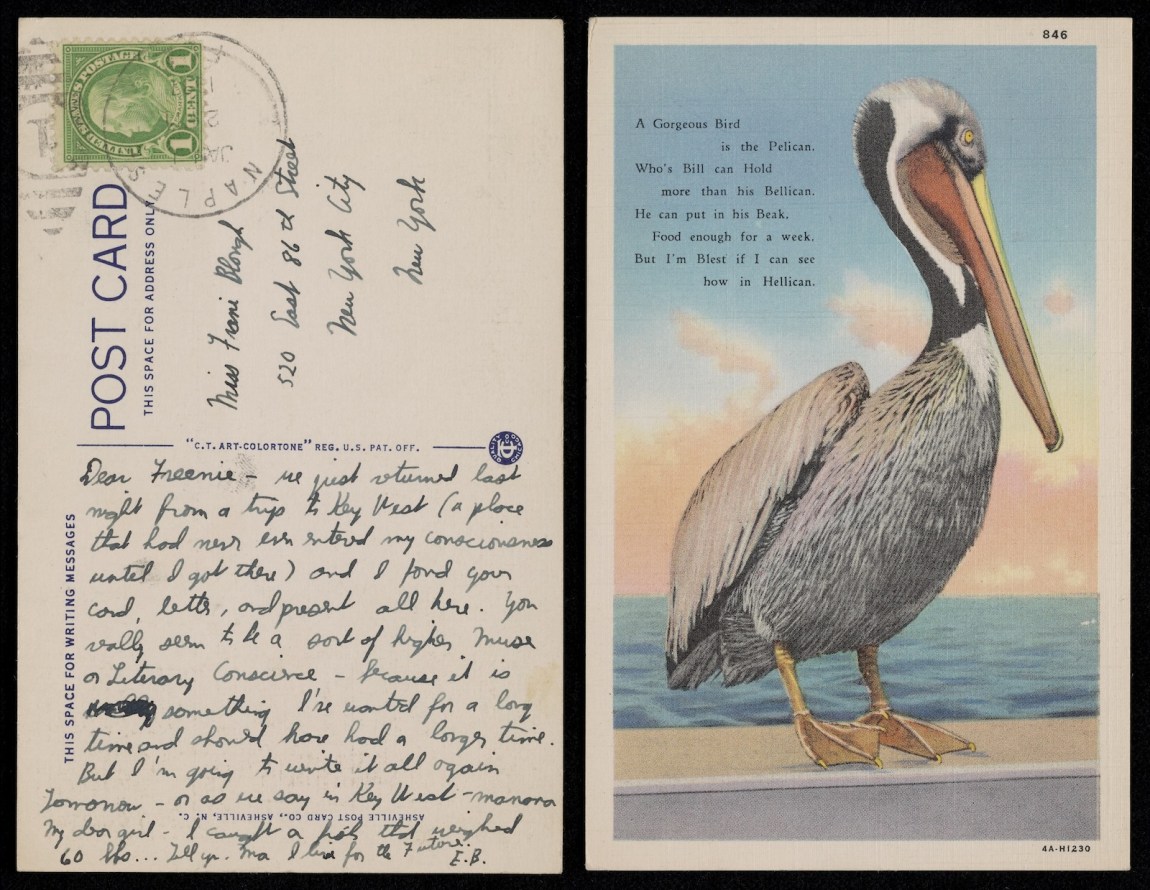

Those lines were eventually engraved on Bishop’s tombstone, a testament to how she and her art remained susceptible and vulnerable. James Merrill said that she was “open to trivia and funny surprises, or even painful ones, today a fit of weeping, tomorrow a picnic,” and her postcards often feel like trial runs for the observational tragicomedies of her poetry. “At first I hated everything,” she writes from Seattle to a friend in 1966, “now after ten days I am beginning to find it all awfully funny.” Looking through the exhibition, flicking back and forth between pictures and words and trying to glean the conversation between them, I often thought of one of Bishop’s favorite writers, Edward Lear—the poet-artist who once spoke of “this ludicrously whirligig life which one suffers from first & laughs at afterwards.” On the front of one postcard she sent, one of Lear’s favorite birds even turns up, decked out in a limerick:

A Gorgeous Bird is the Pelican,

Who’s Bill can Hold more than his Bellican.

He can put in his Beak,

Food enough for a week,

But I’m Blest if I can see how in Hellican.

On the reverse side of the card Bishop signs off with “I caught a fish that weighed 60 lbs . . . Tell yr Ma I live for the future,” which would seem to imply that the poet, like the bird, is planning ahead. Yet there’s always a sense, too, of danger—and of past and present threats to happiness. This “gorgeous” specimen reminded me of Lowell’s comment to Bishop many years later when, having encountered one of her poems in The New Yorker, he wrote: “I have been rereading Lear (Edward) whom you like so much. I guess it would be far-fetched to find his hand here; yet I think he would have enjoyed your feeling, your disciplined gorgeousness, your drawing, your sadness, your amusement.”

Unpublished postcards written by Elizabeth Bishop courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Vassar College Library

A postcard sent by Elizabeth Bishop to Frani Blough Muser, circa late 1930s

Amusement at sadness—and vice versa—was the special province of another of Bishop’s great loves, Buster Keaton, who once told his father that a good comedy could be written on a postcard. Whatever else it is, the postcard is a tight spot—a place where a stoic comedian might thrive, or at least survive. Bishop often sent postcards of Keaton stills, and once noted that “any of Buster Keaton’s films give one the sense of the tragedy of the human situation, the weirdness of it all, the pathos of man’s trying to do the right thing—all in a twinkling, besides being fun.” Her admiration of him comes through in a poem she wrote, entitled simply “Keaton,” in which, despite his “small jaw” and “small brain,” he is finally given a voice with which to say that he will “solve the appointed emergencies”:

Advertisement

If the machinery goes, I will repair it.

If it goes again I will repair it again.

My backbone

through these endless etceteras painful.

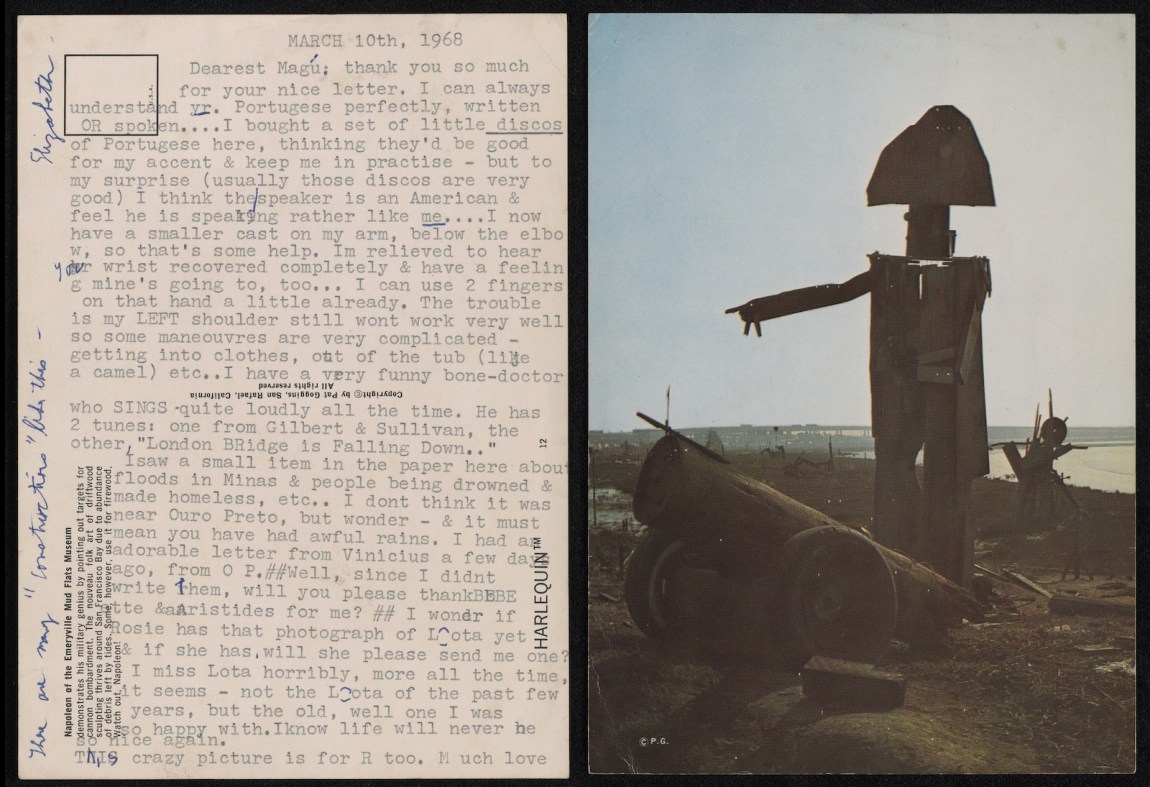

Keaton’s is an art of salvaging and small victories, of being in a fix and of making do. I guess it would be far-fetched to find his hand in a postcard Bishop sent a friend in March 1968, showing a driftwood sculpture of Napoleon “pointing out targets for cannon bombardment” in the mudflats of Emeryville, California. The caption explains that “the nouveau folk art of driftwood sculpting thrives around San Francisco Bay” because of the abundance of debris left by the tides: “Some, however, use it for firewood. Watch out Napoleon!”

Unpublished postcards written by Elizabeth Bishop courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Vassar College Library

A postcard sent by Elizabeth Bishop to Magú Costa Ribeiro showing a driftwood sculpture of Napoleon in California’s Emeryville Mudflats, March 10, 1968

The conquering hero’s fragile body isn’t the only one at risk. Bishop updates her correspondent on various injuries she’s recovering from (wrist, elbow, and shoulder), and adds:

I have a very funny bone-doctor who SINGS quite loudly all the time: he has 2 tunes: one from Gilbert & Sullivan, the other “London Bridge is Falling Down..”

I saw a small item in the paper here about floods in Minas & people being drowned & made homeless, etc . . .

I miss Lota horribly, more all time, it seems—not the Lota of the past few years, but the old, well one I was so happy with. I know life will never be so nice again.

The funny bone-doctor (almost, but not quite, a funny-bone doctor) is perhaps making the best of it, or putting a brave face on things—just as Bishop, or Keaton, or the creator of a driftwood sculpture might do. But then the switch to a “small item” and one of those endless painful et ceteras tells of larger movements of the tides, and of more bodies at the mercy of the elements. And from there Bishop (herself feeling homeless at this moment in her life) is cast adrift into other wreckages: the recent breakdown of her relationship with Lota de Macedo Soares, and Lota’s subsequent suicide. (Bishop’s own injuries were sustained while she was grief-stricken in the immediate aftermath of Lota’s death.) Well might she say, along with her Keaton, “I lost a lovely smile somewhere,” and dream with him of “a serious paradise where lovers hold hands/and everything works.”

*

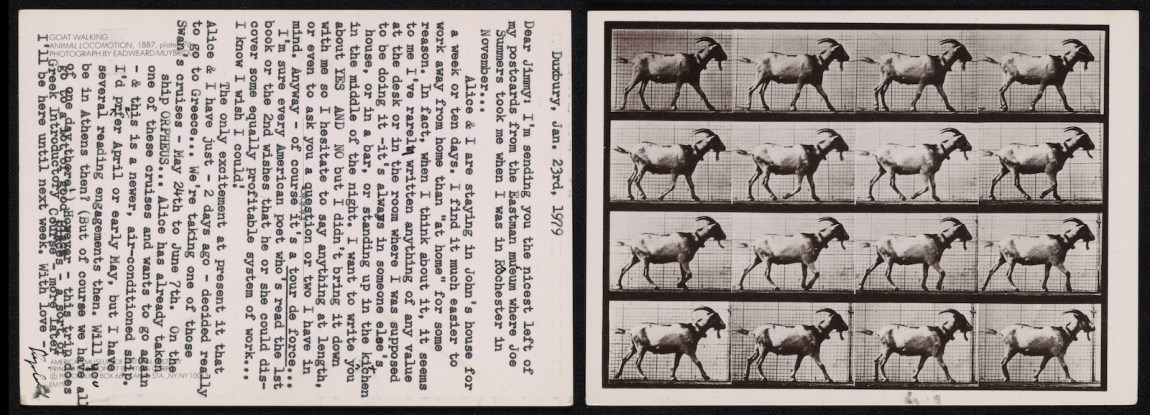

The art of losing seeks expression in many ways in Bishop’s postlapsarian world. In a card from 1978 to James Merrill, she laments that “Letter-writing seems to be my lost art—well, and so is poetry-writing, I’m afraid, or almost. There is always too much to say.” In the space between “almost” and “too much” the lost-and-found art of the postcard comes into its own. In another card to Merrill, reproducing a series of Eadweard Muybridge’s pictures of a walking goat, the postcard-prose-poet again travels from picture to words, always on the hoof:

I find it much easier to work away from home than “at home” for some reason. In fact, when I think about it, it seems to me I’ve rarely written anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it—it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.

Maybe Bishop was never entirely at home anywhere; but then where, after all, is a poet “supposed to be doing it”? She is the artist of odd places and unlikely connections, and this aspect of her creativity is brought to the fore by Ellis and Rosenbaum’s decision to arrange the exhibition by subject rather than chronology. Indeed, chronology is one of many things Bishop plays around with as she goes over what she punningly refers to in one poem as “old correspondences.” In 1972 she sends her beloved Aunt Grace a postcard she found “in the junkshop—mailed in 1914, in Canada too!”

Unpublished postcards written by Elizabeth Bishop courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Vassar College Library

A postcard of Eadweard Muybridge’s Goat Walking (1887) sent by Elizabeth Bishop to James Merrill, January 23, 1979

The whole show sheds new light on Bishop’s relish for what she called “the always-more-successful surrealism of everyday life.” It speaks for the poet who is often “Finding fun in dead amusement parks,” the one who can rhyme “extraordinary geraniums” with “assorted linoleums,” the one who will happily begin a poem by saying “They have set up the carnival, the carnival/In the back-lot of the burnt-out cigar factory.” Bishop loved writing letters, she said, “because it’s kind of like working without really doing it.” Kind of like, yes. Even when not working on poems, she is frequently drawn to visual and verbal similitudes. In a tribute to Marianne Moore in 1948 she confessed that “It is annoying to have to keep saying that things are like other things, even though there seems to be no help for it.”

Not merely annoying, as she well knew, but also enlarging. One late postcard from Truro, Nova Scotia, is accompanied by her sense that “One feels as if one were living—over & over to infinity—the last pages of a Chekov story.—I never thought Truro was like Chekov—but it is!” Elsewhere she sends a card of her “very favorite church in the whole world—like a lop-sided little Chinese package outside, & inside absolutely gorgeous.” She might as well be describing her own poetry, or those moments in the postcards themselves when simile works new magic on her encounters with the world, such as a meeting with seal pups at the Washington aquarium: “they all got up out of bed so to speak (it was late) & craned their necks like a lot of sunflowers, and then looked disappointed—eyes full of tears—when I returned with no fish.”

Postcards also seem to have influenced Bishop’s experiments in photography, collage, and painting. Her description of Joseph Cornell’s boxes in the poem “Objects & Apparitions”—“scarcely bigger than a shoebox . . . Monuments to every moment,/refuse of every moment, used:/cages for infinity”—houses a postcard aesthetics of sorts, and Ellis and Rosenbaum point out that many of her photographic slides and watercolors were postcard-sized. “From time to time I paint a small gouache or watercolor and give them to friends,” she wrote in a letter. “They are Not Art—NOT AT ALL.” But then Bishop had long been interested in the Not Art inside Art, and in the idea that refuse has the potential to be something more than itself.

One of her best watercolors, Tombstones for Sale, became the jacket illustration for the original edition of her Collected Prose. It shows a blossoming poinciana tree, and behind it a shack with tombstones out front, each marked “for sale.” She based it on a linen postcard she mailed to her Aunt Grace in 1957, which featured the tree but no tombstones. (These items aren’t included in the exhibition, although the curators do mention them in passing.) “All the trees laughed at some joke,” Bishop wrote in one poem. It’s not clear whether the tree in Bishop’s watercolor is in on the joke, but, like the tombstones, it would appear to intimate that life goes on and somebody’s got to make a living. (One person’s death may keep another person in business.) On looking more closely, one also sees that in each group in the painting—tombstones to the left, flowerpots to the right—the central figure makes a modest bid to be “special” by standing out from the crowd: a cross here, a dash of blue paint there.

All this, and more, from the humble beginnings of a postcard street scene. “Here’s this modest postcard,” Bishop wrote to a friend in 1978. Yet twenty years earlier she had singled out precisely this quality when writing to Lowell of the artists and writers who were most important to her:

That strange kind of modesty that I think one feels in almost everything contemporary one really likes—Kafka, say, or Marianne, or even Eliot, and Klee and Kokoschka and Schwitters…. Modesty, care, space, a sort of helplessness but determination at the same time.

The postcard—another contemporary form—gave Bishop a space to explore what it might mean to be helplessly determined.