On the map Falcon Reservoir widens the course of the Rio Grande for sixty miles, its waters spreading into Texas and Tamaulipas. But from many perspectives on the ground, that blue webbing is nowhere to be seen. There’s no water—only thick thornscrub. Standing at the edge of the lake feels like peering into a forest. In July 2022 the reservoir reached a record low, only to break that record again two months later. Though it recovered a few feet in 2023, the reservoir is still at only 15 percent of its capacity. Like many rivers around the world, the Rio Grande is dying.

It’s also being turned into a site of death. In September the UN’s International Organization for Migration declared the US–Mexico border—which follows the river’s course through all of Texas—“the deadliest land route for migrants worldwide.” Since March 2021 the Texas National Guard has been deployed there, including to a camp on the shore of Falcon Reservoir, to patrol in helicopters and armored personnel carriers, and to mount razor wire fences. In July, invoking the Texas Disaster Act, state authorities laid concrete on the riverbed to anchor a thousand-foot span of buoys intended to block migrants from swimming across. When a body was found caught in the buoys in early August, Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, called for their immediate removal, but Texas governor Greg Abbott doubled down. Abbott shirked responsibility for the deaths, stating through a spokesperson that drownings in the river were common occurrences. That much is true: Between January and August of 2023, over five hundred people lost their lives crossing the US–Mexico border, some drowning and others perishing from exposure to the elements.

Joe Biden ran for office on the promise that he would not extend the border wall. In October, however, he announced contracts for seventeen new miles in South Texas. To facilitate construction, he announced waivers for twenty-six federal laws, including the Endangered Species Act and the Clear Air Act. In places, the planned wall cuts through tracts of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, which protects the little remaining undeveloped land in the region and serves as a corridor for migrating animals. Meanwhile, Texas’ state government has moved to build its own border wall, defying the Endangered Species Act, for which it has no waiver.

At the upstream end of Falcon Reservoir, retreating waters have likely uncovered the stone plaza and sandstone rubble that is left of the old townsite of Zapata—ruins that speak to a long history of interlinked violence against people and the environment in South Texas. For two hundred years Zapata was a community stitched to the Rio Grande. Residents drew on its water for their household needs, planned their summer crop plantings around its seasonal floods, and crossed the bridge over it to buy groceries and see family on the other side, in the Mexican town of Guerrero.

The buildings around the town’s central plaza—a two-story courthouse, the Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, and the primary school that doubled as a movie theater—were built from sandstone hand-cut from the banks of the Rio Grande. The town’s dirt roads would shift during flood season, following new paths that rain carved toward the river during storms. “I would go and sit on the riverbank, just listening to the water gurgling and watching it flow. It mesmerized me,” Hildegardo Flores, now eighty, told me about his childhood in Zapata. “I would come home and build my own river, a little canal between our two orange trees.”

All that changed in 1950, when the governments of Mexico and the US began construction on the Falcon Dam downstream. They aimed to control flooding, provide water to farmers near the mouth of the river, and regularize its course: left to its own devices, the Rio Grande shifted across a wide floodplain, moving the international border line with it. Three years later they closed the dam, creating Falcon Reservoir (also known as Falcon Lake) and inundating Zapata and surrounding towns. Residents were cut off from the river as well as from Guerrero, which was relocated some forty miles away. The reservoir forged a kind of lacustrine border wall long before wall-building became US policy.

Today, many residents of contemporary Zapata live in subdivisions and manufactured home parks near the lake, while the town’s businesses and municipal buildings are strung along a highway. The local economy centers on the fisheries of Falcon Lake, which the state stocks with bass, gar, and catfish. Flores was ten when the dam closed. “Our old life—it was gone,” he said.

*

Before it was settled by Spanish colonists, the area now known as Zapata was inhabited by dozens of nomadic groups that scholars later referred to collectively as the “Coahuiltecan Tribes.” According to the historian Juliana Barr, during the middle of the eighteenth century these groups incorporated the Spanish missions of the Lower Rio Grande “into an old pattern of subsistence, seasonal migration, settlement, and alliance.” The tribes and the Spanish colonists joined together against the Apaches, from whom they both suffered raids. Yet over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the colonizers’ “civilizing mission” brought about detribalization and cultural erasure at the same time as European diseases ravaged native populations.

Advertisement

Zapata originated as a porción, or land grant from the Spanish crown. In 1750, after a Spanish expedition surveyed the area, a New Spain–born settler named José Cristóbal Ramírez arrived and began ranching. Seventeen years later, having demonstrated that his agricultural activities had improved the lands, he received the title to them. His son inherited the land and lived with his wife, María, on the north side of the river; the town of Falcón slowly grew around their sandstone house. The town of Zapata, named for a rancher who had died defending the Republic of the Río Grande, developed thereafter, also on a Ramirez porción.

Up to the middle of the twentieth century communities on the two sides of the Rio Grande were connected by family ties, migratory labor, schooling—many children spent years at a time on each side so that they would be educated bilingually—and amateur baseball leagues. At the start of the twentieth century, however, things had started to change downriver. As the geographers Christian Brannstrom and Matthew Neuman have recounted, in 1904 a railroad connected Brownsville, at the mouth of the Rio Grande, to Corpus Christi, then the southernmost edge of Anglo Texas. Land development and irrigation companies emerged to subdivide and sell off rangelands to newcomers, bringing Anglo settlement into what was then still staunchly Hispanic territory.

In 1908, 24,000 acres were under irrigation in the so-called Magic Valley; by 1930, that figure had climbed to over 400,000. In 1910 Sunset magazine wrote that “primitive wilds…are being rapidly transformed into a domain of farms and gardens.” A developer’s pamphlet advised in 1918 that to bring water to one’s land, all you had to do was “telephone-for-irrigation.” So many did that after a few decades of cabbage and citrus farming, the once-navigable river had dropped to shin-height. Farmers began to fear that their crops would fail in the event of a drought. At the same time, Mexican farmers were expanding the amount of land under irrigation on the Tamaulipas side of the river. In 1938, recognizing that there was not enough water to go around, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas—the US’s three Rio Grande Basin states—entered into an agreement regarding their shared river.

As the increasing pressure on the river became clear, the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), the joint US–Mexico agency charged with administering the rivers that span the two countries, took note. They sponsored a shared surveying expedition, and in 1944 the countries signed a treaty apportioning the Colorado River, Tijuana River, and the Rio Grande. They also agreed to collaborate on the construction of two dams. The lower of the two would be completed within eight years: the allocation of water outlined in the treaty depended on it.

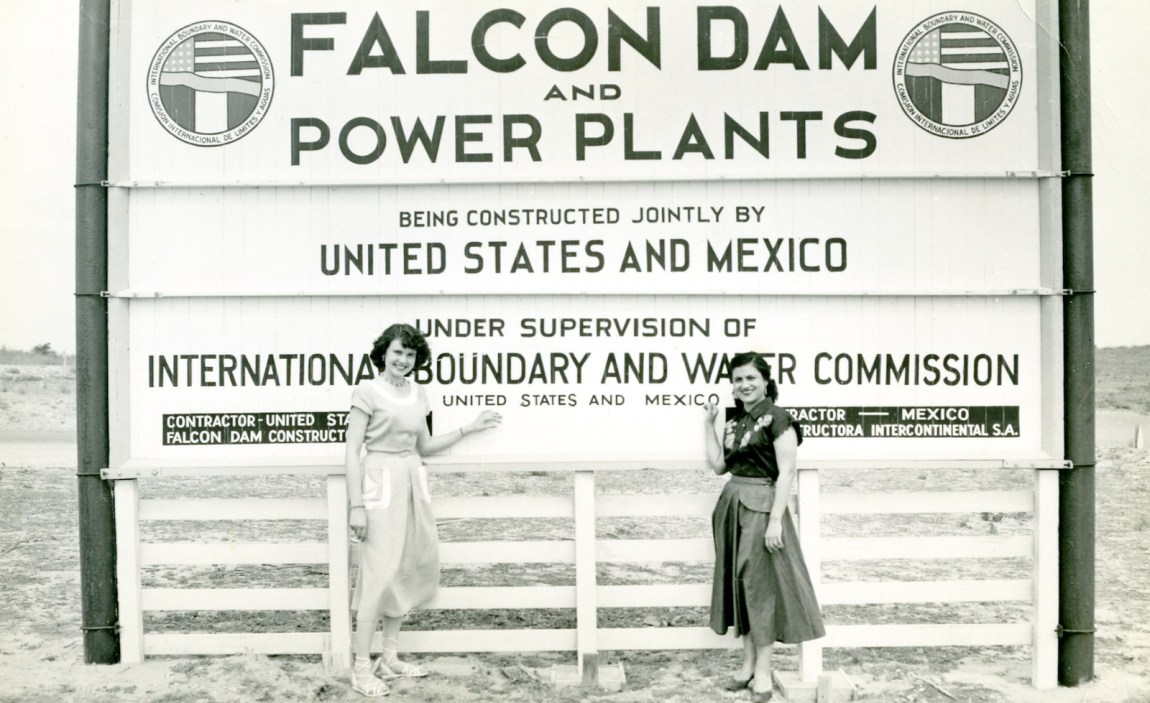

Falcon Dam was the first major dam to be jointly constructed by two nations on an international border. At the time the border wasn’t marked by anything besides the river. With the 1944 treaty and the creation of the reservoir, the IBWC also oversaw the construction of concrete monuments and massive steel-laminate buoys to mark the line. The governments shared the dam’s eighty-million-dollar cost. Because the treaty only allowed each country to build within its own borders, the project was also shared by two construction companies, Falcon Constructors and Constructora Intercontinental. Laborers were only authorized to work on their side of the river, with exceptions for carpenters who built identical forms together.

The reservoir they built was long, thin, and shallow: sixty by eleven miles when full, storing four million acre-feet. The construction crews also built two identical power plants, one on each side of the border, and six fifty-foot discharge gates to release the river’s flow. But to make this possible, around five thousand residents of the historic towns within the reservoir’s projected boundary—including Zapata, Falcón, Lopeño, Santo Niño, Santa Rosa, Sabinito, and Soledad on the Texas side—learned that their homes would soon be underwater.

IBWC officials told members of the condemned communities that the lake would take three or four years to fill, and that they would not have to move until indemnification monies were paid in full. The compensation wasn’t much: The IBWC itself determined the homes’ market value, then subtracted 40 percent: 20 percent for depreciation and a further 20 percent for obsolescence. The agency also argued that its responsibility was limited to acquiring land, not building a new town. It took until 1951 for county officials to put enough pressure on federal legislators to persuade the IWBC to plan a new townsite.

Advertisement

Some moved to the new Zapata ahead of schedule, like Hildegardo Flores’s family, who used their own funds to relocate and rebuild Flores’s grandfather’s two-story wooden house and grocery store. But many didn’t want to leave their homes until they had to. Still others didn’t understand what was happening, because the federal agencies had never sent representatives into the region’s more isolated towns. The biggest project locals had seen up to that point had been the construction of the suspension bridge across the river, replacing a hand-rowed ferry. “The people never realized they were going to stop the old Rio Grande,” Tomás Izaguirre, then eighty-five, told the Valley Monitor in 1993. “They didn’t believe the engineers, and they stayed until the last minute—they never had a person explain correctly what was going to happen.”

*

It did not take three years for the lake to fill. The dam was closed in April 1953, and on August 23 thunderstorms broke out, marking the beginning of nearly a week of torrential rain. The waters rose fast, filled with lumber from broken houses. The residents of Falcón, Lopeño, Ramireño, Zapata, and Guerrero fled without their possessions. Carmen Bustamante, who was twenty-three at the time, left Lopeño with her family in a truck as the waters rose. “We loaded up and took pictures off the wall,” she recalled in a 1993 article in the Houston Chronicle. “The water was waist-high. We wanted to save as much as we could, but we forgot about the chickens.”

The Red Cross arrived with tents, in which most of Lopeño’s residents lived for six months. Even those who had anticipated the move suffered. As there hadn’t been enough carpenters or house movers to relocate the town, nothing was finished. “It was a harsh, unkind winter,” recalled Elena Flores Stokes at a July 1999 panel discussion reported on by the newspaper LareDOS. “All you could hear that winter was the sas-sas-sas of an axe hitting wood.” On the other hand, the rain was a godsend for those who supported the dam. The wife of a county judge recalled that “a lot of us who were for the dam were praying that the lake would fill.” The summer had been very dry up until August. “Then the miracle happened. It started raining and rained hard for six days before Eisenhower came. When he came, there was a beautiful lake behind the dam.”

Eisenhower and Mexican President Adolfo Ruiz Cortines came to the Rio Grande Valley on a 90-degree October day. They met on the top of the dam and delivered speeches from the soil of the other’s country. “The Falcon Dam symbolizes in a most special way the desires of our countries to join their efforts in the sphere of cooperation imposed on them by their neighborhood, to facilitate…the forward march of social and economic progress,” said Ruiz Cortines. The New York Times reported that the decision to focus on friendship and cooperation was an effort to “skirt” political tensions. In the preceding years Mexico’s foreign service had regularly expressed concerns about violations of the 1944 water treaty and argued that overuse by Texas farmers often left the city of Matamoros, in Tamaulipas, without water. US officials, meanwhile, had been complaining that their government was suffering excessive criticism in the Mexican press.

At the new townsite of Guerrero, the two heads of state watched huapango and norteño dancers and a thirty-piece orchestra flown in from Mexico City. Though local newspapers printed photographs of Zapata County residents waving cordially to the president as his motorcade advanced toward the dam, Bustamante, who was still living in a Red Cross tent, staged a small protest. She held a sign: “The Falcon Dam refugees welcome Pres. ‘IKE’ to observe the scenery. These were our homes now they are TENTS!”

Bustamante voiced the anger that others restrained. The dam had been announced just after the end of World War II, to a community already reeling from the deaths of its young men. When they were displaced, they lost their homes and lands, their animals and their farm equipment. Before the dam, families had passed ranchland through generations with a ceremony, tossing dirt in each cardinal direction and calling the porción by its religious name. After the dam, the land was gone—and with it, the tradition.

By severing the community from its land and water, the dam made a decisive border where there had been a porous boundary. “We lost so much of our culture when we were uprooted for the reservoir,” said Flores Stokes.

The conviviality of our community, which was not just Zapata but also Guerrero—that was gone. Those ties were two hundred years old. We lost language…We lost recipes and stories and ways to behave. We lost the place we bought sugar, coffee, meat, tequila, and medicine. Everything about our lives had been defined by this river.

After the relocation many people never learned to swim, out of a mixture of fear and anger. Flores’s grandmother often told him that she feared that rains would come again and the lake would rise to wipe out the new Zapata.

That didn’t happen. Instead over the last four decades Falcon Reservoir has spent increasingly prolonged periods in retreat. IBWC planners knew that the Rio Grande fluctuated, but in their allocations they optimistically projected strong flows, thus setting the river up to be overstressed as consumption rose and climate change diminished the snowpack on the mountains that feed it. In 1983, the first time the reservoir’s levels dropped for an extended period, the residents of Zapata returned to their old town’s central plaza, now above water, and held a dance.

*

In early June 2022 I drove to Zapata, staying in a combination motel–trailer park on what was once the edge of Falcon Lake. Now the view was of a lot of thornscrub. Before the construction of the dam, the biologist Michael Small told me, there wouldn’t have been so much brush. The Rio Grande’s biannual flooding and shifting course cleared out the scrub and allowed a tall forest canopy to grow along the river. Those forests were cleared for dam construction and farming; infrared photography shows that since 1900 over 99 percent of the river’s riparian forest has been cut down.

The Rio Grande Valley is renowned for its bird life. Its subtropical climate makes it “a dividing line where species that occur further north and further south come together,” Small told me. People travel from all over the US and beyond to spot gray hawks, green kingfishers, great kiskadees, and seedeaters. Several towns along the river have bird sanctuaries. But the loss of the forests reduced the avian diversity, too—some depended on the high canopy.

Even if the falling waterline has exposed Old Zapata’s plaza again, there won’t be a dance this time around. Much of the site has been looted, and the area is sealed off by border security. Signs on the motel premises warned, “Crossing into Mexico Could be Dangerous: Report Criminal or Suspicious Activity by Calling the Zapata County Sheriff’s Office.” And just up the road was the the Texas National Guard encampment, part of Governor Abbott’s anti-migration Operation Lone Star.

Since the early 2000s the communities of the Rio Grande Valley have been subjected to increasingly intense border militarization, first by the federal government and now by the state of Texas. The most visible of these measures is the construction of the border wall, made possible thanks to the 2005 REAL ID Act (which most of us know because it required us to get new drivers’ licenses for taking domestic flights). A rider on the act authorized the Secretary of Homeland Security to waive any legal requirements—namely, environmental regulations—that might stand in the way of border wall construction. According to the historian C. J. Alvarez, the concession was so broad in scope that the only precedent that lawmakers could find was the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act.

By 2016 the vast majority of California, Arizona, and New Mexico’s border was walled. But Texas only had substantial stretches of wall surrounding El Paso and Brownsville, at the mouth of the Rio Grande. The next year, Trump issued an executive order mandating the construction of additional wall, among other border enforcement measures. From January 2020 on, landowners in Zapata County received notifications that Customs and Border Protection was going to begin requesting right of entry onto their properties. The area was not, and is not, a common migration crossing site, and most residents opposed the wall, whether because of its symbolism, the environmental damage, the loss of property, or the belief that it’s a “stupid waste of money,” the anti-wall activist Scott Nicol told me in a phone call. Some of those in its proposed path were the same families whose homes had been expropriated for Falcon Dam decades ago, including Zapata County Judge Joe Rathmell, who denied surveyors right of entry to condemned county-owned land, aiming to save the bird sanctuary in the town of San Ygnacio.

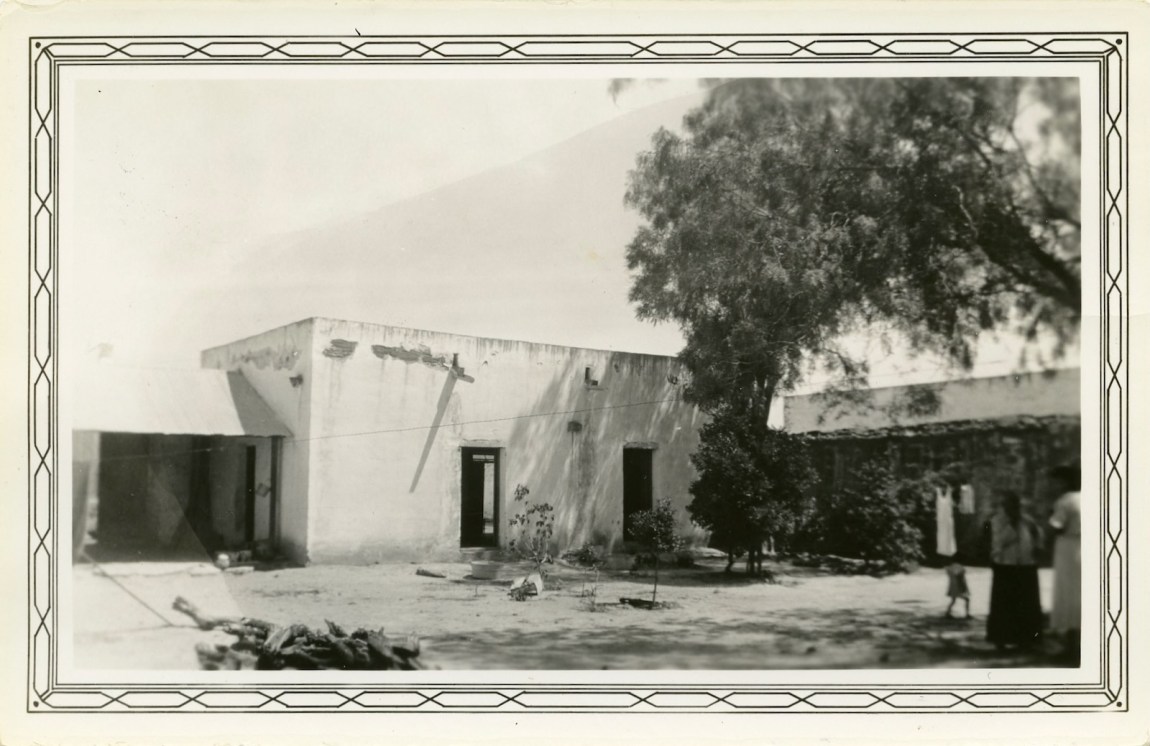

Sixteen miles upriver from the contemporary site of Zapata, San Ygnacio was initially condemned by the IBWC but left intact.1 Considered the last site of nineteenth-century vernacular architecture in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, it’s a vision of what old Zapata might look like today had it not been inundated: sandstone houses arranged on dirt roads surround a central plaza. Some people keep livestock in their yards; others have semi-trailers parked out front, suggesting that they make their living elsewhere. Christopher Rincón, who directs the River Pierce Foundation, a historic preservation organization founded by the artist Michael Tracy, gave me a tour of the Treviño-Uribe Rancho, a 1830s sandstone courtyard house that is listed as a National Historic Landmark. He told me that there had been plans to encourage the National Parks Service to designate San Ygnacio and its surroundings as a National Heritage Corridor, which might have helped drive cultural tourism. But they gave up in the face of the proposed construction. “Building a wall here would ruin everything about this place,” he said.

When I visited, the conflict between Zapata County and the federal government had not been resolved, and no wall had been built through San Ygnacio’s bird sanctuary. But just days before, as I was driving to Zapata, Biden had made his first border-wall construction announcement: that he would construct eighty-six new miles to “fill gaps” in the wall built under Trump. Renewed environmental assessments were underway. At the same time, Governor Abbott was awarding contracts for the construction of a state border wall, planning to use leftover panels fabricated for the Arizona wall to follow the path of the Trump wall that Biden had canceled, including through Zapata County and neighboring Webb and Starr Counties. I spoke about the renewed uncertainty with Debralee Rodriguez, who directs a conservation organization called the Valley Land Fund that had fought a years-long battle under Trump to save another bird sanctuary, just below the dam, from border wall construction. Would they have to start afresh? She sighed like she never wanted to talk about it again: “I thought we were done with that.”

Instead, after the decision to fill gaps in Trump’s wall, this past October Biden announced that seventeen new miles of wall would be built through Starr County. He claimed his hands were tied: since Congress had made the wall appropriations, the executive branch didn’t have the authority to cancel them. Because of this, residents believe a similar announcement for Zapata and Webb is imminent: those counties’ wall appropriations were also made by Congress, in the fiscal year following Starr County’s.

In San Ygnacio, I walked through town and took the path down to the bird sanctuary on the bank of the river. The sanctuary is rigged with surveillance equipment: cameras, solar-powered lights, and a dirt road for “cutting for sign”—the Border Patrol’s practice of dragging tires to smooth the surface, which they later check for footprints. Still, for someone familiar with the walled border of Arizona and California, it felt miraculous to be able to stand at the very edge of the river with no steel bollards cutting in between. I could imagine how the river had captivated a young Hildegardo Flores, and why it had felt so integral to Old Zapata. Now that many of us have come to think of rivers as natural boundaries that divide communities and nations, it’s easy to forget that there’s another way to see them: as soft tissue in the landscape that nourishes and connects everything around it.

In the era of dam-building, authorities turned the natural landscape into an early form of border infrastructure. The unruly Rio Grande had to be held behind an earthen embankment and confined to a channel when allowed to proceed. In making the landscape rigid and functional, they also wrung the life out of Zapata and its surrounding communities. Now the eradication of difference once directed at the people of Zapata has turned into a war on the poor and transient. As the landscape shrivels, politicians are turning to new tools to make the river into a boundary. People die falling from the steel wall built on the river’s banks; bodies turn up in the netting of the buoys cemented to its bed. At sites along the Rio Grande, the Texas Rangers have clear-cut all vegetation, saying they can’t leave anywhere for someone to hide.