A dispatch from our Art Editor on the art and illustrations in the Review’s February 22 and March 7 issues.

As a kid in Canada, I’d read and reread The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats. I think it may have been responsible for why I live in New York now. The book’s vision of a city winter—snow-covered brownstones and streets, stoops and vacant lots—instilled in small me a romantic vision of Gotham that never left. After a three-inch snowfall in Manhattan, my daughter, along with the rest of the city’s kids, had a snow day this week—and this newsletter comes after a brief snowball fight using meager snowballs scooped from car hoods. Returning inside, we made potato prints, and while I worked she reread some of her own favorite books.

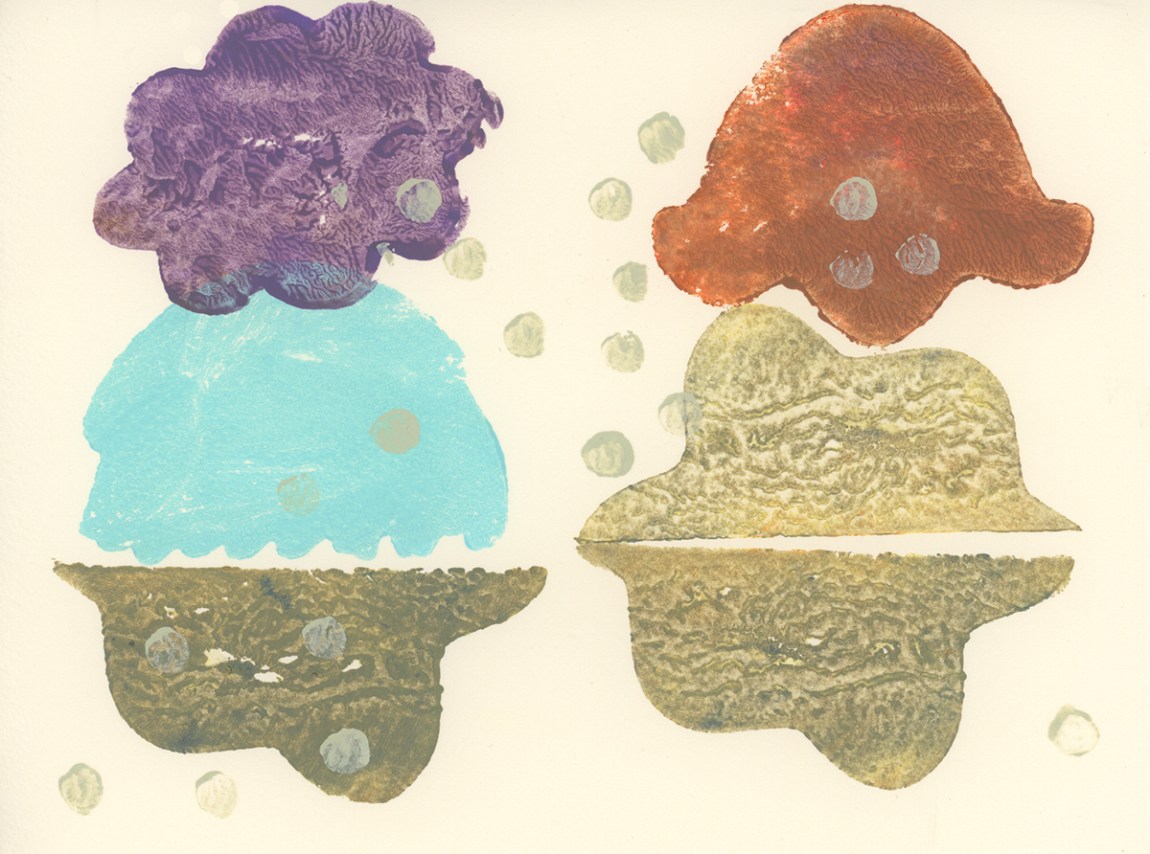

The cover art in our February 22 issue is the painting Drops (Green, Turquoise, Peach) (2023) by Corydon Cowansage, an artist based in upstate New York. I saw her work in a group show in 2022 and thought that her shapes and colors would look good on our cover. While thinking up cover lines, our editor nicknamed the painting “Willy Wonka babka,” which I thought was a nice bit of art writing.

Inside, for a piece by the historian Sean Wilentz arguing that Trump should be disqualified from running for president under the Fourteenth Amendment, I contacted Anthony Russo, a seasoned illustrator I’d worked with regularly when I was the art director for the Times Op-Ed page.

For Emily Raboteau’s review of two books about environmentalism and maternalism, our assistant editor Nawal Arjini suggested a leafy Honey Pierre composition called My Mother’s Garden (2023). Montrealer Alain Pilon made a subtly villainous portrait of George Santos for Andrew O’ Hagan’s essay about the former New York congressional representative and perennial fabulist.

Andrea Ventura turned in a sweet, doleful portrait of the Cuban novelist, essayist, and musicologist Alejo Carpentier for Natasha Wimmer’s review of two new translations of his work.

I wrote to Geoff McFetridge after reading Natalie de Souza’s essay about Alzheimer’s, dementia, and aging. Geoff sent four of his paintings that he thought might suit the themes of faltering memory and hope. We picked a seated figure, facing an atomizing mirror image. I reminded myself to ask Geoff where I could watch Drawing a Life,” a film about him and his art practice directed by Dan Covert and released last year.

For a review by Ava Kofman of Kerry Howley’s book Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs, about the trials of the whistleblower Reality Winner, we asked the Belgian illustrator Fien Jorissen for a portrait that also mapped a few parts of Winner’s experiences. Kofman’s review made me curious to see Susanna Fogel’s film adaptation of Winner’s story, which premiered at Sundance this year.

The series art for this issue, titled “Mad Molecules,” is by the London-based illustrator and artist Paul Davis.

Our March 7 cover features My Work Is Done Why Wait (2022–2023), a painting by the Los Angeles–based, German-born painter Friedrich Kunath. I made an informal studio visit on a recent trip to LA, and when I read Robert Pogue Harrison’s double review of In Praise of Failure: Four Lessons in Humility by Costica Bradatan and The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings by Geoff Dyer, I remembered the stacks of books—Thomas Bernhard, Marguerite Duras, Goethe—piled in Kunath’s workspace, and also his vast collection of tennis racquets. We don’t often reference a specific story on the cover, but Kunath’s painting seemed to match a tone of melancholy found in a handful of essays in the issue. It was a near-unanimous choice in our six-person cover meeting.

Oliver Munday, a designer, illustrator, and art director for The Atlantic, took on Jeffrey Toobin’s article about the Trump-appointed judges on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, and gave us a brilliant collage tied to Toobin’s contention that “the Fifth Circuit is afire.” Sophia Martineck contributed a triple portrait of grief-stricken Emerson, Thoreau, and William James for John Banville’s review of Three Roads Back,by Robert D. Richardson, a study of how the three writers dealt with loss.

For Mary Wellesley’s essay about the lives of and expectations for medieval women, I asked John Broadley for an illustration. As is his wont, he went over and above my own expectations, delivering “a face made up of constituent parts based on some of the incidents in the text, and medieval imagery in general.” Wellesley herself wrote to compliment the art, which is always a nice bonus.

When I’ve commissioned Michelle Mildenberg in the past, I’ve asked for portraits, but this time we sent her a draft of Kristen Martin’s review of two books on modern motherhood and the state. Mildenberg gave us a multifaceted breakdown of the issues, foregrounding a mother and child against depictions of people working alongside (or against) mothers.

Advertisement

I loved the discussion of classifications and archetypes in Merve Emre’s review of Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney and Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton. The Dutch artist Ruth van Beek makes wonderful comparisons in her work, and she put together a grid of dolls’ socks that worked well with the piece. For a review by Josephine Quinn of the historian Peter Brown’s memoir, we asked the Tennessee-based artist John Brooks, who happened to be in LA, for an illustration. He was leaving town before he had a chance to photograph the finished portrait, so I suggested he drop it off at my boyfriend’s office to be scanned. Since I usually work almost entirely digitally, encountering the drawing of Brown in its original poster-sized format gave me new respect for Brooks’s practice.

The series art for the issue was done by the inimitable Tom Bachtell. He usually works in portraiture and caricature, so I was happy to see him go abstract with his “Brush Dances.”

All the snow on our block melted overnight. By the time we made our early trek to the bus stop for school the next day, it was gone. I despair that Keats’s picture book is becoming an abstract artifact of history for my daughter, instead of the promise of a cityscape that it was for me.