On October 13, 1966, the artist Marta Minujín invited sixty Argentine celebrities to a large room, ushered them to seats that were each equipped with a television set and a radio, and filmed and photographed the group for hours. Twelve days later about half of them came back to the same space, wearing the same clothes, and took the same seats, at which point footage of themselves appeared from all sides on the TVs and walls. At the same time, Minujín took over the broadcasts of two radio stations and Channel 13, one of Argentina’s free-to-access television stations, to announce a media invasion.

Prior to the performance Minujín had worked with the social research department at the University of Buenos Aires to identify five hundred people who could join from home. On October 25, when they tuned into the event, they received phone calls and telegrams delivered to their houses by performers dressed as mail carriers. Meanwhile, on their TVs, they saw other at-home participants pick up the telephone and answer the door. “You are a creator,” the messages informed them. But they had also become, according to Minujín, “prisoners of the media.”

The resulting artwork, Simultaneidad en Simultaneidad (Simultaneity in Simultaneity), was likely, as the critic Michael Kirby pointed out in 1968, the first to combine several forms of mass media in a live performance.1 Initially Minujín and her collaborators had envisioned it as a three-city project connected by satellite: Allan Kaprow in New York and Wolf Vostell in Berlin planned to reproduce the same events in their cities. But only Minujín was able to pull of the technological feat; according to her collaborator Leopoldo Maler, she installed two hundred antennas on the roof of the Torcuato di Tella Institute, then the hub for boundary-pushing art in Buenos Aires. Simultaneity in Simultaneity was not just an impressive technical achievement but also a prescient vision of the all-encompassing media environment of today.

Now eighty-one, Minujín is perhaps Argentina’s most famous contemporary artist. She grew up on the second floor of a building in the San Cristóbal section of Buenos Aires—where she still keeps her studio—with her father, a physician of Russian Jewish descent; her mother, a poet and pianist; and her older brother, who died of leukemia when Marta was a teenager. The building’s first floor was occupied by Casa Minujín, a workwear manufacturer founded by her grandfather. From an early age she made art inspired by nature and classical music; at twelve she enrolled in the Escuela de Bellas Artes Manuel Belgrano. In her teens she also audited classes in painting, sculpture, engraving, and drawing at schools around the city and met the Informalist painter Alberto Greco, who was known for relief-like compositions featuring found materials. Under his influence she started to incorporate mundane objects, like pieces of cardboard from old paint boxes, into her abstract work.

In 1961 Minujín traveled to Paris on a scholarship from Argentina’s National Endowment for the Arts. It was the first of several extended stays in the French capital, where she fell in with the Nouveau Realistes, a group founded by the art critic Pierre Restany and the painter Yves Klein. The Realistes used a range of materials and media to achieve, in Restany’s words, a “poetic recycling of the real of the city,” fashioning elaborate assemblages and collaborative works that often incorporated performances and destructive interventions (décollage). Niki de Saint Phalle, who became a close friend of Minujín’s, was the group’s only female member. In her notorious series Tirs (“shooting paintings”), from the early 1960s, she offered audience members a rifle and directed them to shoot at white plaster reliefs concealing bags of paint, tomatoes, and eggs.

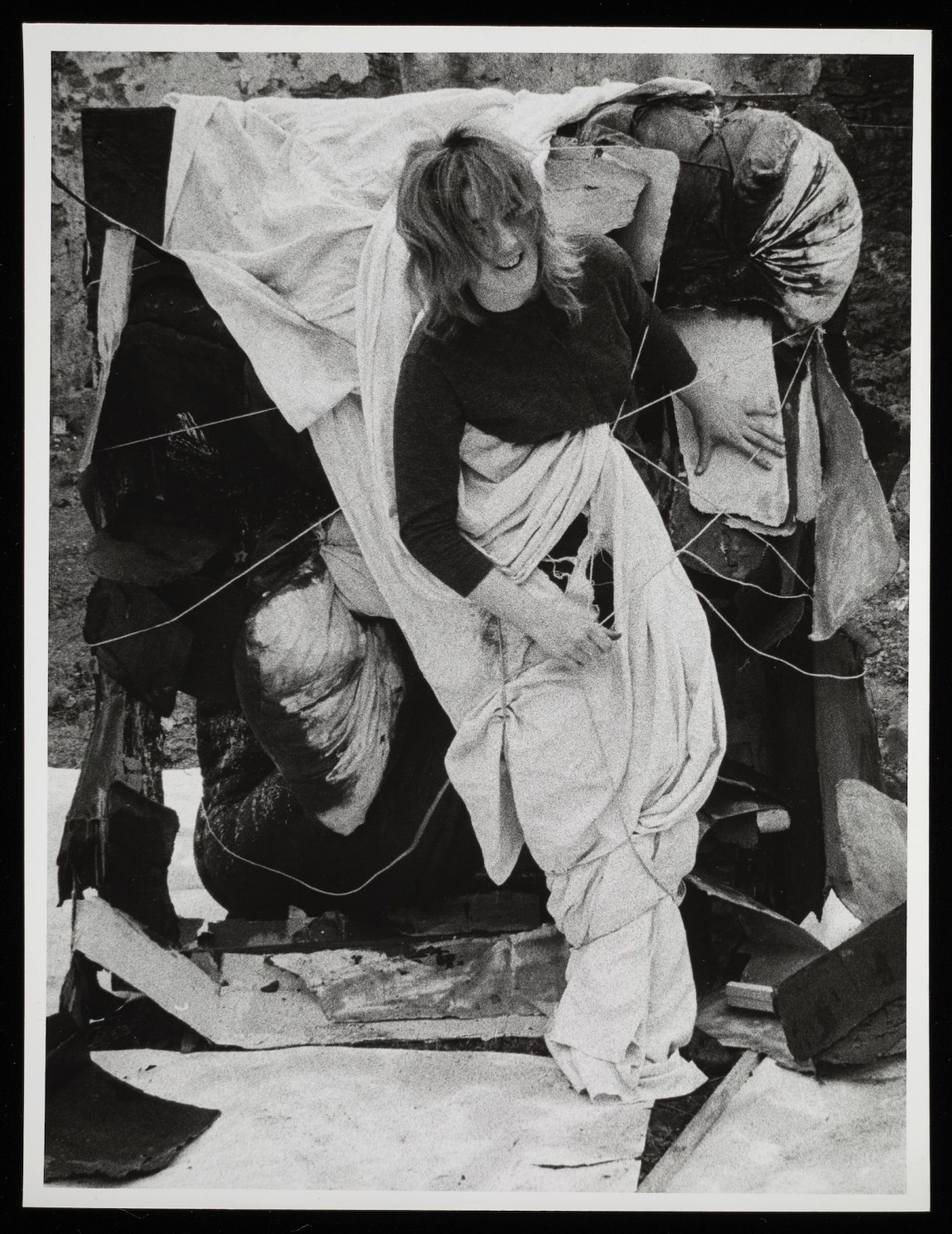

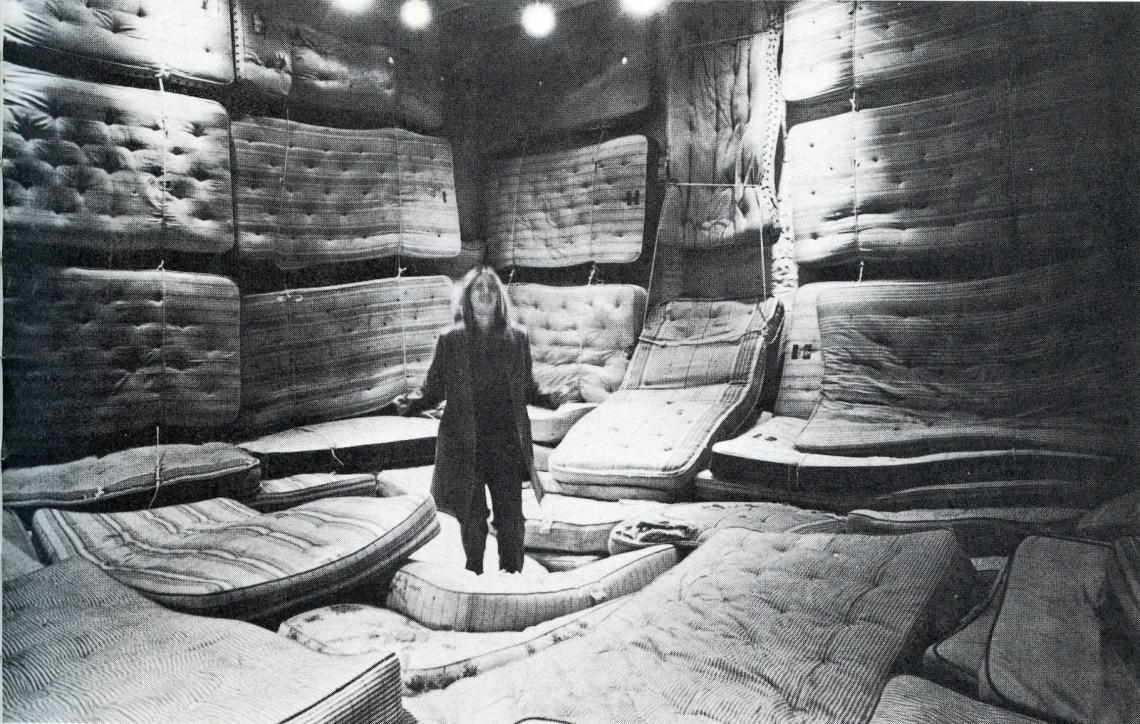

Minujín’s recycled materials of choice came from used mattresses scavenged from a local hospital, which she transformed into soft sculptures. From the fabric and stuffing, she hand-sewed weighty biomorphic forms that she painted with candy-colored stripes and wove into knotty, intestine-like assemblages, some of which people could crawl inside. These tactile sculptures offered her ways to make audience members active participants. In 1963 she invited a group of colleagues—among them the mononymous installation artist Christo—to an empty lot in Montparnasse known as the Impasse Ronsin, which several artists had used for actions, including Saint Phalle’s shooting sessions. With paint and axes, the group vandalized Minujín’s cardboard and mattress sculptures before she doused the works with fuel and burned them. The performance came to be known as The Destruction.

In 1964, at the end of her second stay in Paris, Minujín attended the Venice Biennale, where Robert Rauschenberg won the Golden Lion, confirming the international dominance of American Pop Art. Minujín remembers the trip to Venice and Milan, where she bought her first miniskirt, as the moment she “went Pop.” Back in Argentina, she created her first interactive installation, ¡Revuélquese y viva! (Wallow Around and Live!, 1964), an environment made of colored mattresses within which the audience could frolic. Soon after, she took over a late-night television program called La campana de cristal and filled the studio with bodybuilders, chickens, balloons, and horses lugging open paint cans that dripped on the floor.

Advertisement

The following year, Minujín collaborated with the artist Rubén Santantonín on her most ambitious environment yet. A self-taught artist a generation older, Santantonín shared her preoccupation with pop culture and kitsch. Much like her, he was suspicious of the staid art object consecrated in museums: Santantonín coined the term arte-cosa (art-thing) to describe his fragile, nameless works made from cardboard, rags, and string. Working with the artists Floreal Amor, David Lamelas, Leopoldo Maler, Rodolfo Prayón, and Pablo Suárez, Santantonín and Minujín created La Menesunda—Buenos Aires slang for Mayhem.

With a budget of 2 million pesos (about $8,230 in 1965) and access to expensive hardware from the Di Tella family’s SIAM appliance conglomerate, the team worked out of Minujín’s family home to design a labyrinth of eleven environments, including a refrigerated chamber, a room with a couple in bed, and another in the shape of a woman’s head lined with cosmetics. The sensory experience included concocted smells—fried food, a dentist’s office—and music that evoked the neighborhood’s streets. Thousands of visitors to the Di Tella Institute waited in lines that stretched down Calle Florida during the two weeks La Menesunda was open. Drifting through the installation’s cacophonous “television tunnel,” visitors passed TVs tuned to various channels alongside closed-circuit feeds that screened their own movements back to them.

*

Minujín has often described art as a way to intensify experience, to live more fully and immediately. In a fragment from her notes that was published in the catalog of a 2010 retrospective at the Latin American Art Museum of Buenos Aires, she describes the “vertigo” of art-making and “living in your own creation whirlwind” in which the hours disappear.2 The French philosopher Roger Caillois, in his 1958 sociological study Man, Play and Games, defined games “based on the pursuit of vertigo” using language that could also describe Minujín’s approach: they attempt, he wrote, “to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind.”

In the late 1950s some artists found that they could inflict voluptuous panic on audiences using what Allan Kaprow called “happenings”: semi-improvised affairs traversing various media including music, theater, poetry, and visual art. These chaotic and playful events frequently took place in constructed environments or installations that demanded direct audience engagement: Claes Oldenberg’s Ray Gun Spex (1959) at Judson Memorial Church in New York featured comic skits and an auction in which viewers could bet on pieces of junk with “funny money.”

Minujín expanded on the form. Inspired by the theories of Marshall McLuhan, the experimental performances of Fluxus, and the nascent arte de los medios movement, she developed a new kind of happening that involved manipulating the incident using technologies like video and the distribution channels of broadcast media. Wolf Vostell became the first artist to use working televisions in a happening in the late 1950s, and Nam June Paik distorted television images into abstract forms with a magnet in 1963, but Minujín and Santantonín, in La Menesunda, were the first to use closed-circuit television to bring footage of the audience into a happening, confronting spectators with evidence of their own unwitting performances. By courting widespread media attention and spectacle, Minujín also expanded the reach of such happenings, which became quite popular in Argentina.

Two years later, in her contribution to Expo 67 in Montreal, Minujín became one of the first artists to organize a live performance with the help of a computer, which processed mail-in surveys published in local newspapers to select thirty participants and sort them into groups based on their sex, hair color, and stature. Then she persuaded those correspondents as well as eight celebrities—including famous athletes, actors, and writers—to participate in another media “invasion,” photographing and recording them from all sides. From above, four hovering helicopters transmitted images of the public as they walked around the pavilion.

Advertisement

One of the challenges of mounting a retrospective exhibition of Minujín’s work is its ephemerality. She burned her early mattress sculptures in The Destruction to prevent them from ending up in what she called “cultural cemeteries,” and her subsequent happenings were by nature fleeting and context-specific. Her first US survey exhibition, Marta Minujín: Arte! Arte! Arte!, now on view at the Jewish Museum in New York, takes an archival approach. The curators, Darsie Alexander and Rebecca Shaykin, juxtapose documents of her performances and monuments with a selection of her artworks, ranging from an early painting she made collaboratively with Alberto Greco to new mattress sculptures like the monumental Intertwined Concepts (2019–2022), whose gabardine protuberances stick out like tongues.

Joining them are six of her Frozen Sex paintings, inspired by her conversations with a New York sex worker, which depict genitals in cold, abstracted compositions. When canvases from the series were first shown at the Arte Nuevo gallery in Buenos Aires in 1973, the police arrived within three hours and closed the show for obscenity. When they were shown later that year in Washington, D.C., Minujín and several performers left the opening night at the gallery to cover the lights at the nearby Washington Monument with filters, bathing the obelisk in fleshy pink light.

Photographs and films, meanwhile, show Minujín in action: floating down the Río de la Plata in a suit made of newspapers that slowly dissolve in the water, lying bikini-clad in a tarp as collaborators tossed dirt collected from Machu Picchu onto her body, picking up a call in her psychedelic Minuphone booth, paying the Argentine foreign debt by giving corn that had been spray-painted orange (“Latin American gold”) to Andy Warhol, speaking into a megaphone in front of a replica of Dublin’s James Joyce Tower covered in bread. A haunting slide show depicts the group of artists at the enflamed Impasse Ronsin during The Destruction. A 16mm film by Leopoldo Maler documents conservatively dressed porteños navigating La Menesunda for the first time.

The archive makes clear how much Minujín risked in these provocative encounters, many of which are unlikely to recur—at least not in their original forms and not in settings sanctioned by art institutions—due to changing cultural mores and concerns over safety, privacy, and consent. She contracted infections from her found mattresses. When El Batacazo (The Long Shot, 1965–1966), an installation that included live rabbits and flies, traveled to New York City, it was shut down by animal protection groups after several of the rabbits died. At times Minujín herself was overwhelmed by the chaos she generated: during her happening Suceso Plástico (Visual Event, 1965), in which she dropped lettuce, flour, and five hundred live chickens from a helicopter over a soccer stadium in Montevideo, she had second thoughts about exposing the audience and actors to danger. It became, in her words, her “last violent happening.”

*

In June 1966 a coup installed an authoritarian military government that ruled Argentina for the next seven years. The regime, led at first by General Juan Carlos Onganía, cracked down on academic, artistic, and intellectual freedom—a precursor to the large-scale program of murder and violence carried out by the country’s next military junta during the Dirty War of 1976–1983. Onganía abolished university autonomy and censored books, films, plays, and art. He also campaigned against what he deemed “immoralism,” banning popular countercultural signifiers like long hair on men and miniskirts.

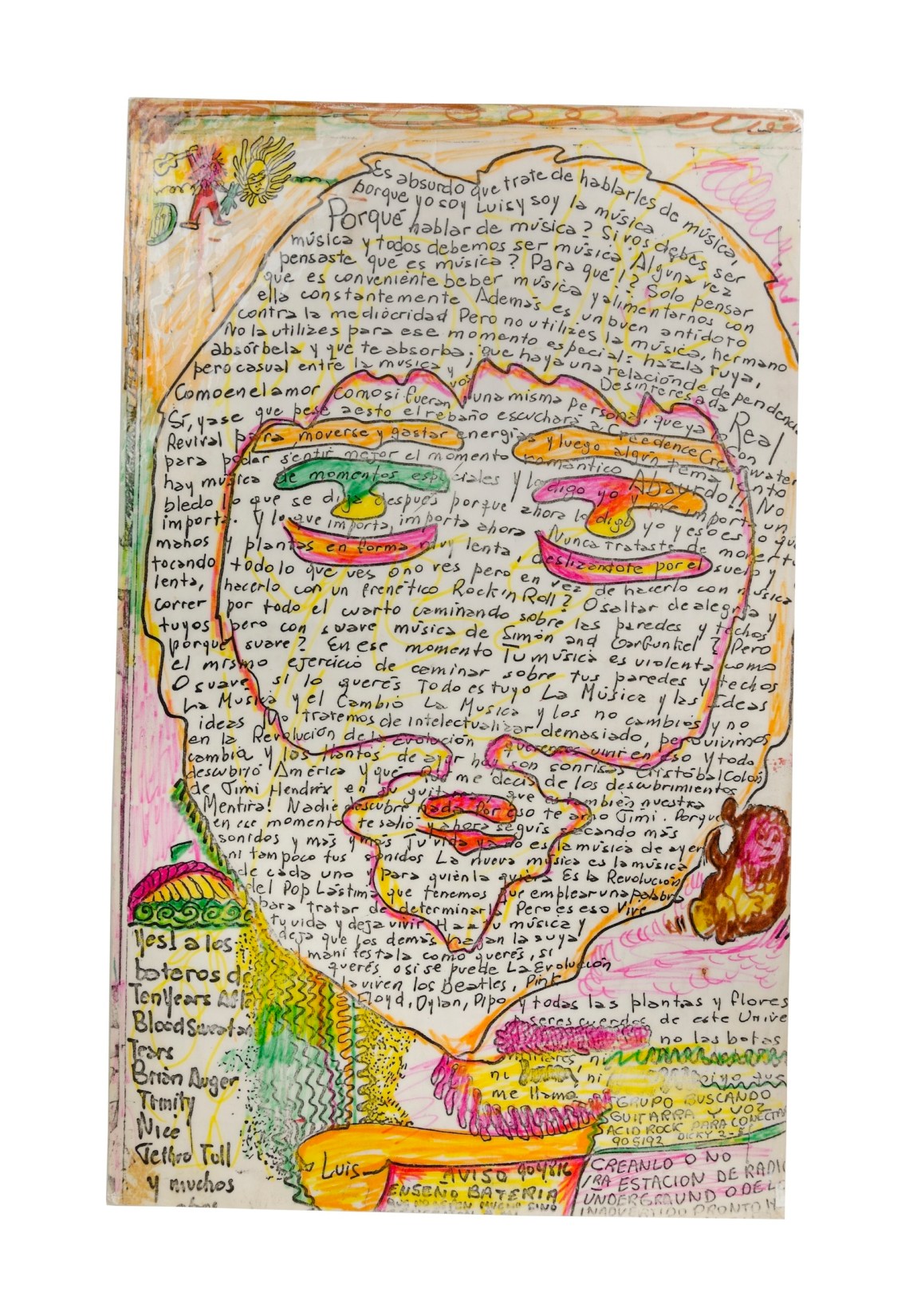

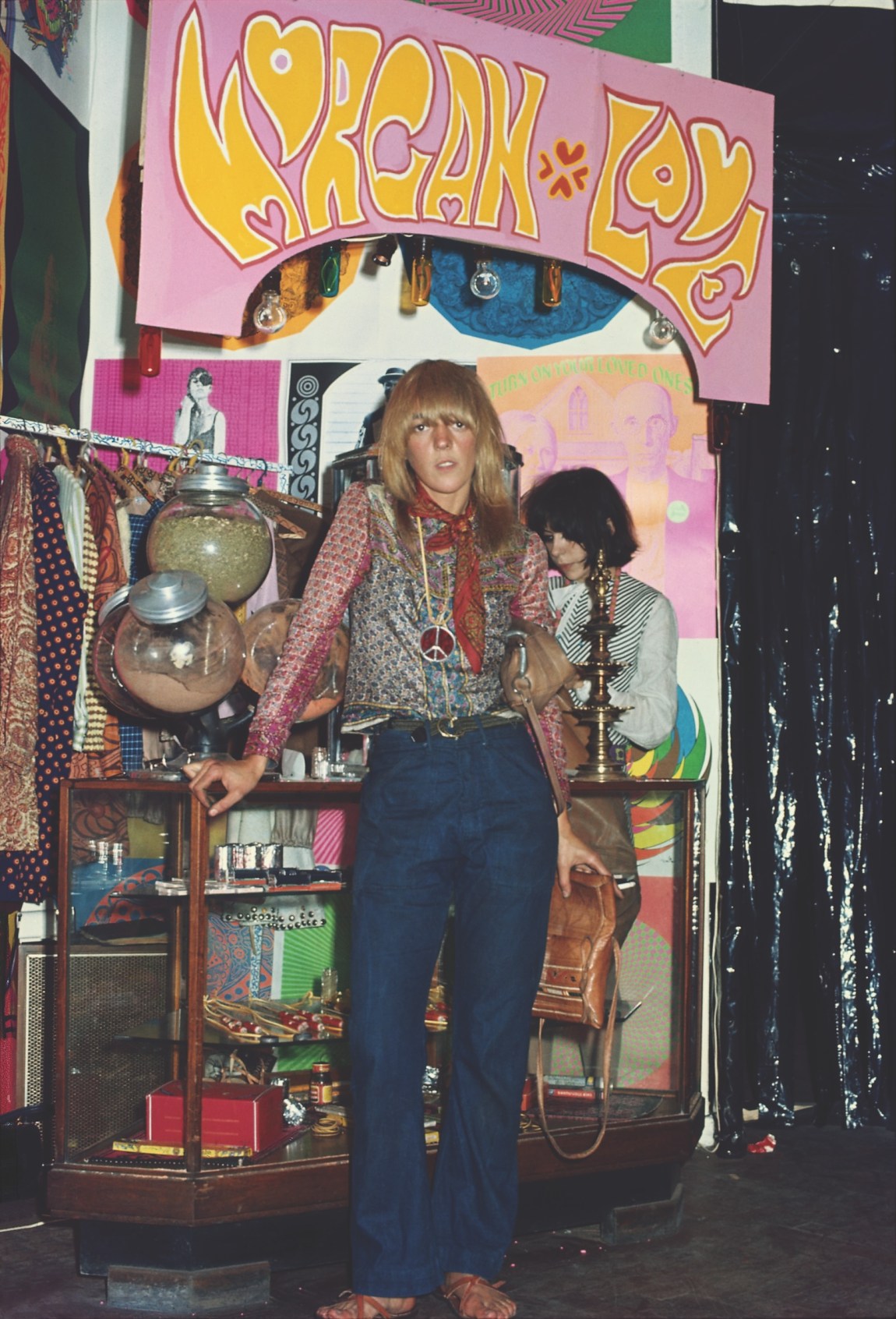

During this period Minujín, who recalls that she and her son received threats from the far-right Tacuara Nationalist Movement, made several trips to the United States, where she found new collaborators in Pop and avant-garde circles, including Warhol, Charlotte Moorman, the Judson Theatre Company, and even Salvador Dalí. From sending up mass media and popular culture, she shifted to making happenings that reflected her marginal position as a Latin American artist in the New York art scene and evoked the turbulent state of her home country. On a trip home in 1968, having experimented with LSD in New York and briefly lived in Central Park, she premiered an installation at the Di Tella institute, Import-Export, that brought hippie culture to Buenos Aires. A photograph on display in Arte! Arte! Arte! shows her in bell bottoms and a peace sign medallion surrounded by psychedelic posters, a rack of paisley duds, and jars of incense, which visitors perused to the scent of sandalwood and the sound of Hare Krishna drummers.

That Minujín managed to mount work like this under the dictatorship was remarkable. She may have had more room to maneuver thanks to her considerable celebrity, which gave her opportunities to live and exhibit abroad and could have afforded her a degree of protection at home. “It was less likely that a death squad would come to the door of a famous person’s house,” she told Victoria Noorthoorn, the curator of the Buenos Aires retrospective, in 2010.

But her criticisms of the regime were also more indirect than the overtly political and activist work of the avant-garde conceptual movement that arose in Argentina in the late 1960s, most notably the Group of Vanguard Artists, whose exhibitions were repeatedly censored and shut down by police. (Several of the group’s members later stopped making art and joined guerilla movements.) In their most famous action, Tucumán Arde (Tucumán Is Burning, 1968), they collaborated with labor unions, scholars, and other experts in a collective campaign to expose the poverty and starvation in Tucumán province after the government closed the region’s sugar refineries.

Minujín spent much of the early 1970s in the United States, where she undertook a series of happenings that culminated in a piece called Kidnappening (1973). During a memorial performance celebrating Picasso at the Museum of Modern Art following the painter’s death, select spectators were blindfolded and whisked away to undisclosed locations, among them Max’s Kansas City, a barbershop, and the Brooklyn Bridge. It was an ambiguous action, at once dark and playful. Made in a period of frequent coups and widespread political unrest in Latin America, it now also seems to have anticipated the mass kidnappings in Argentina during the Dirty War.

*

Minujín returned to Buenos Aires in 1975 after three years in New York, a year before a second coup overthrew Isabel Perón and established another military dictatorship. During this period she met daily with fellow artists, including her close confidant Federico Peralta Ramos, for long conversations at the Florida Garden cafe downtown. These discussions inspired new works about the country’s sense of hopelessness. A memorable display in Arte! Arte! Arte! features material from La Academia del Fracaso (The Academy of Failure, 1975), a ten-day conference she and Augustín Merello held at the Center for Art and Communication in Buenos Aires. By attending lectures, performing exercises, and taking vaccines and potions to ward off delusions of grandeur and “triumphalism,” students could earn a degree certifying their liberation from a success-obsessed world. The cap and gown were a burnt tailcoat (frac-asado) and a crown of thorns.

Two years later, once the military dictatorship had come to power, her mordant performances again became what the Jewish Museum catalogue calls “indirect protests.” In her 1977 piece Espi-Art (Spy-Art), visitors were invited to observe many of Argentina’s then best-known artists—among them Eduardo Costa and Clorindo Testa—through peepholes along a narrow corridor. In sixteen small cubicles they performed a variety of actions, including simulations of torture, such as the conceptual artist Juliano Borobio chopping up what looked like body parts.

Minujín’s sculptures soon moved into public settings and took on monumental proportions. In the ongoing Fall of Universal Myths series, begun in 1978, she tips life-size replicas of well-known monuments—including Big Ben and the obelisk at the center of Buenos Aires’s Plaza de la República—on their sides. For these colossal projects, teams of construction workers erect metal scaffolding and in some cases cover it in plastic-wrapped food that later gets distributed to the spectators—in the case of the obelisk, sweet bread.

In 1983, after the fall of the junta, Minujín oversaw the construction of a half-scale model of the Parthenon and covered it with more than 20,000 books that had been banned under the military government. Cranes then tilted the temple onto its side and workers unwrapped the structure, letting the crowd take the books. One of the more amusing documents at the Jewish Museum is a letter Minujín sent the McDonald’s corporation in the 1980s requesting sponsorship for a horizontal Lady Liberty covered in ground beef. Performers would climb firetruck ladders to cook the meat with flamethrowers and assemble it into hamburgers for the audience. McDonald’s thanked her for the proposal but declined to fund the project.

In recent years, in addition to more toppled monuments around the world, Minujín has returned to the mattress, creating new sculptures as well as paintings that feature dizzying abstractions made with thousands of cotton gabardine fabric strips. Some incorporate bits of neon light and projected images, recalling her early immersive installations and psychedelic experiments. These vibrant, enticing, and relatively medium-sized confections are in one sense the white cube–ready objets that Minujín long resisted making. But in another sense they attest to the paradoxical gestures of The Destruction: in her dramatic attempt to thwart what she saw as the interment of her artwork in museums, she became famous for a groundbreaking career in performance art, now a discipline that institutions are eager to commemorate.

Minujín once described Picasso as “the innovator who shocked the most, to later see these shocks of his turned into canons.” The type of hypermediated art experience that she pioneered in the 1960s has long since entered the mainstream. Now it makes up a robust part of the programming not only at most major museums but also at commercial pop-ups like the Museum of Ice Cream and the Museum of Sex. (In 2019 Minujín told the curators of Menesunda Reloaded at the New Museum that she thinks Disney’s Epcot ripped off one of her designs from the 1965 installation.) Recently Minujín made what might appear to be her own contribution to the genre with Sculpture of Dreams, a monumental inflatable soft sculpture that became a selfie destination at Lollapalooza Argentina in 2019 and in Times Square this past November.

Such work might seem to show Minujín accepting the commodification of her style rather than pressing ahead to surface new confrontational forms. And yet she has always made art that courts commodification and kitsch only to subvert them. She may not have sold a single piece of art until 1980, but she has always used commercial tactics—from neon lights and bodybuilders to towers of free food—to stimulate her audiences, whether by playing to their narcissism or to what one of the participants in Kidnappening called their desire for “excitement and novelty without any real threat of danger.”

Minujín’s work is “always about the people,” she has said—how they look at themselves, how they behave, and how destabilizing experiences might offer them new ways to be. After the performance, another participant in Kidnappening wrote her a letter. “You have changed my life,” the correspondent said. “That was my first and only night in New York, since I had come from Chicago for the weekend…. You walked up to me and asked me if I wanted to be kidnapped. Of course, I accepted; I love adventures.” Minujín’s collaborators took the letter-writer to the studio of a photographer. The two fell in love that night; they went on to get married. Now “I am truly happy,” the note went on. “If only all the artists in the world dedicated themselves to crossing fates.”