The Dutch artist Jacqueline de Jong loads her canvases with about as much potential energy as they can bear. The paintings in her “Billiards” series induce mild vertigo, so outlandish are their perspectives, so distorted their angles, so broad their crashing planes of color. Wrists cocked, focused but effortless, the subjects—likely fellow Amsterdammers playing carom, the pocketless French version of the game—come as near as painted figures can to action itself. If they liked they could shoot the ball straight into the frame.

De Jong paints them obliquely, almost on the sly, with a delirious Dutch palette and more than a touch of Pop. Four works in the series—eight, really, if you count each of the five canvases that make up Queue (III, V, II, IV, I) (1978), her life-size studies of handsome wooden cues—are up now at Ortuzar Projects in New York. In Op de queue nemen (1977), the gleaming, green-felted table appears on the canvas as a trapezoid set into the floor’s globs of yellow, teal, brown, black, and white. A cheap wooden door, a television, a beer advertisement, and a vase of tulips crown the head of a woman preparing to strike. We see just a sliver of her face, rendered almost as a shadow that recedes into her dark hair and sweater.

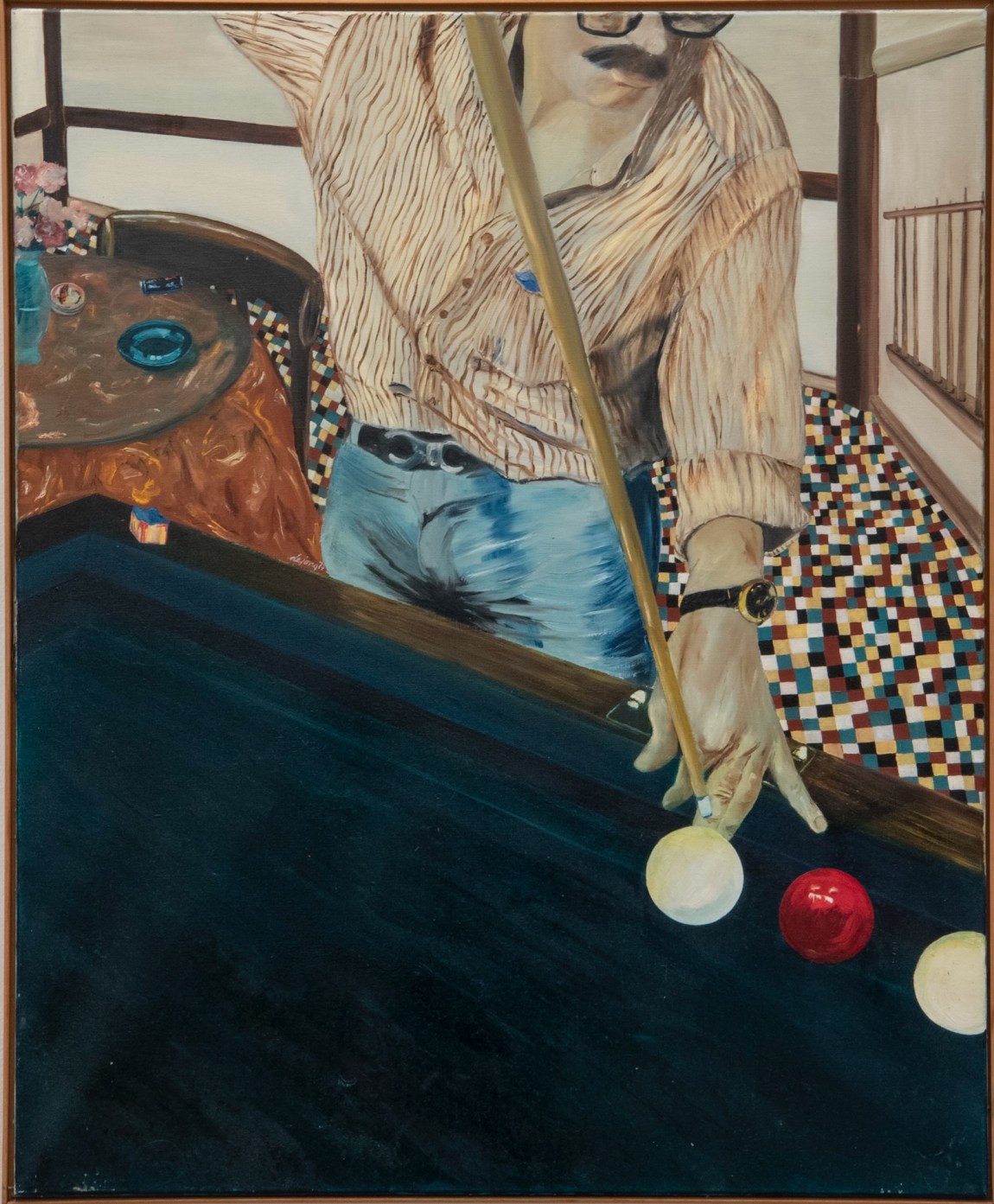

Who might slink over from the depths of the bar? In Tirer le diable par le queue (1978), it’s a slim man, mustachioed, bespectacled, shirt tucked in, belted, his eyes just out of frame, his cue held just so. He’s light years sleeker than the sterile gallery walls on which he’s hanging out. Behind him the same tulips appear next to an electric blue-green ashtray, the center of a vortex that engulfs the billiard table, the pixelated floor, and the walls behind him. Long lines of wood—table, cue, chair, wall—fan out from the bottom-right corner of the canvas. Time is not so much stopped as shoddily dammed: you can almost hear the second hand on the man’s watch tick. The same goes in Crispy Hands (Mains crispés) (1977). All eyes are fixed on the game but ours, drawn instead to the expanse of wall—inexplicably periwinkle—that separates two seductively angled billiards players.

This tavern isn’t the Amsterdam we know from Dutch painting, but the raw drama that de Jong extracts from a game brings to mind vignettes out of Jan Steen, the Golden Age’s great comic painter. The right-hand side of his Parrot Cage (circa 1660–1670), at the Rijksmuseum, is given over to a game of backgammon. The chips and felted wedges aren’t visible: instead the scene is all about the rapt onlooker, his eyes shielded like those of the woman in Op de queue nemen, and the gamesmen, their profiles shaded by hats and their hands hovering over the board, ready to throw the dice.

*

De Jong was born in 1939 to a Swiss mother and a Dutch father, both Jewish, in Hengelo, roughly a dozen miles from the German border. Her father ran a hosiery factory—not an atypical profession at the time for a Jewish man in Holland. The community is as old as the 1579 Union of Utrecht, with which the Dutch Republic outlawed religious persecution and inadvertently welcomed Sephardic refugees fleeing Iberia. They built such national landmarks as the Esnoga—the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, still the city’s most beautiful building. By the turn of the century Dutch Jews were some of the most assimilated in Europe.

Everything changed in 1940, when Hitler invaded and the situation for families like the de Jongs became dire. In 1942 Jacqueline’s father went into hiding; she and her mother escaped with the help of the artist Max van Dam, a Jewish friend of the family who returned from relative safety in Vichy France. The trio almost made it to the Swiss border, then were caught and arrested by German police, sent to a hotel, and instructed to return the next day. But the hotel, de Jong remembered, “was run by resistance people,” who helped her and her mother inch a bit further toward Switzerland; they were stopped again, this time by Swiss customs, before a passerby finally aided them over the border. They made it to Zurich, where they waited out the war. Van Dam, however, was left behind, having followed the German police’s instructions to go back to the station. He was deported and murdered at Sobibor in 1944.

In Hengelo after the war de Jong’s father started up the factory again. The prosperous family collected art, traveling to Amsterdam, Paris, and New York, where they bought a de Kooning. Never keen to become an artist, de Jong was nonetheless noticed by members of her parents’ circle for her painting talent. In 1957 she went to Paris to study French. On her nineteenth birthday her father came to visit and collect a work he had bought from the Danish artist Asger Jorn, a ringleader of COBRA, the avant-garde painting movement named for Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. Soon Jacqueline started dating Jorn; their yearslong relationship would alter her art and politics for good.

Advertisement

Back in Amsterdam, with the help of her father’s friend Willem Sandberg, who since 1945 had been director of the Stedelijk Museum, de Jong orchestrated quite the setup: she worked as his assistant for half a day and studied art history the other half. She applied to the Royal Academy in Amsterdam but was rejected, she later claimed, because of her affiliation with the “avant-garde, politically left-wing” Stedelijk. So she worked for artists instead, and soon started making her own paintings—abstract and anguished, with hints of the violent motifs that would surface in much of her mature work.

Throughout the Sixties she shuttled around Europe with frequent stops in Paris. In 1960 she met Guy Debord, who three years prior had formed the Situationist International, the avant-garde Marxist movement, with Jorn and other artists and intellectuals. De Jong became the seventh Situationist and one of very few women in the group. “I wanted to change the world, society, things,” she recalled. “The after-war-world was not yet global, it was not yet turned over by a real revolt.”

In 1962, after a period of factional disagreements, de Jong left the Situationists. She used the funds from her first painting sales to launch the Situationist Times, a multilingual manifesto-cum-collage. She and her friends filled its pages with essays, drawings, photographs, political programs, musical notation, algorithms. Issues were devoted to such subjects as knots and labyrinths, and each carried the statement: “All reproduction, deformation, modification, derivation, and transformation of the Situationist Times are permitted.” “There are no ‘goals,’” de Jong later said. “Just a free magazine.” She edited the paper in the mornings and painted in the afternoons, shifting from her abstract juvenilia to figuration around 1964. After issue six, published in 1968, she ran out of cash, and that was the end of the paper.

*

In 1970 de Jong returned to Amsterdam for good. She made a series of diptychs—a “Chronique d’Amsterdam”—in acrylic on wood, working the text-and-image form she had developed in the Situationist Times into her art. The point was not to tell the story of her adopted city but to depict the experience of coming to know a place that was in some sense already hers. The works in “Chronique d’Amsterdam” are reproduced in the catalog Jacqueline de Jong: The Ultimate Kiss, published in 2021 on the occasion of a solo exhibition in Belgium, Wales, and Germany, and a retrospective in Toulouse. The diptychs deal extensively, for the first time in her work, with her Dutchness. There are bikers, canals, windmills, and speedskaters, and also activists raising their fists in the air and, in Op ‘t land waar ‘t leven zoet is (1972), images of plein air gay sex behind barbed-wire fences.

This emphatic burst aside, the bearing of local history, politics, nationality, and indeed art on de Jong’s work is ambiguous. Asked in a recent interview whether there is “some kind of ‘Dutchness’” in her consistent use of narrative, de Jong cited Rembrandt, but didn’t elaborate. If she meant simply that she attempts to emulate the master’s storytelling prowess—his ability to compel the viewer to think about his subjects in time—then her later work, perhaps especially her “Série noire,” proves her point.

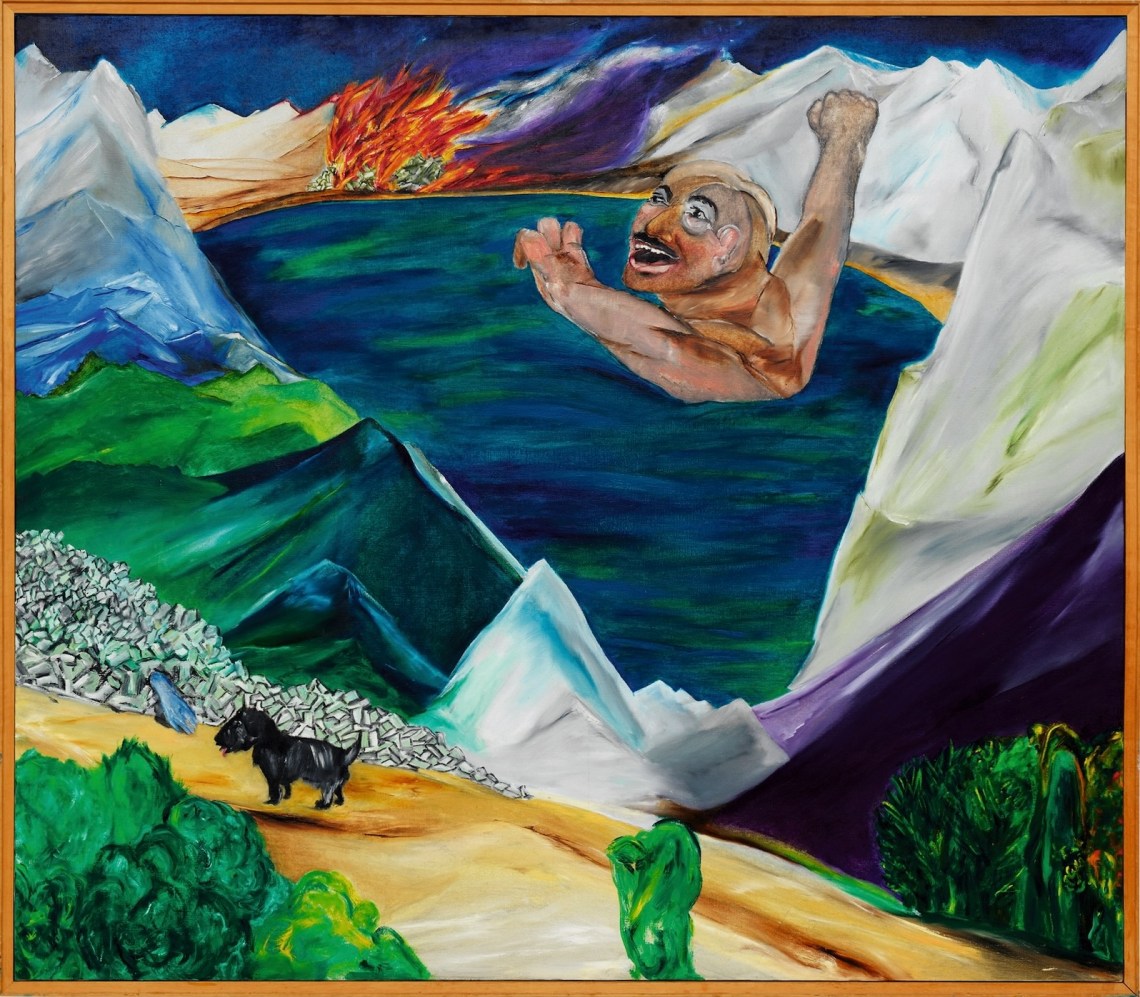

The series, three paintings from which are up at Ortuzar, illustrates violent moments from detective novels and pulp fiction. In L’Âne du Liban (1981), a cheering man—really a mass of muscle, and apparently the murderer from the Lebanese writer Edward Atiyah’s eponymous novel (translated as Donkey from the Mountains, 1961)—emerges triumphantly from the depths of an icy pool. In the distance flames blaze amid snow-covered mountains. In Rhapsodie en Rousse (1981), a stone-cold killer turns away from her victim, dagger in hand. And in Gardez vous à gauche (1981), named for the French writer Paul Sérant’s political essay, de Jong sets a nonchalant killer in a silk polka-dotted shirt, victim in his lap, opposite a listless detective who photographs the scene of the crime. The tableau is eerily reminiscent of Crispy Hands.

Advertisement

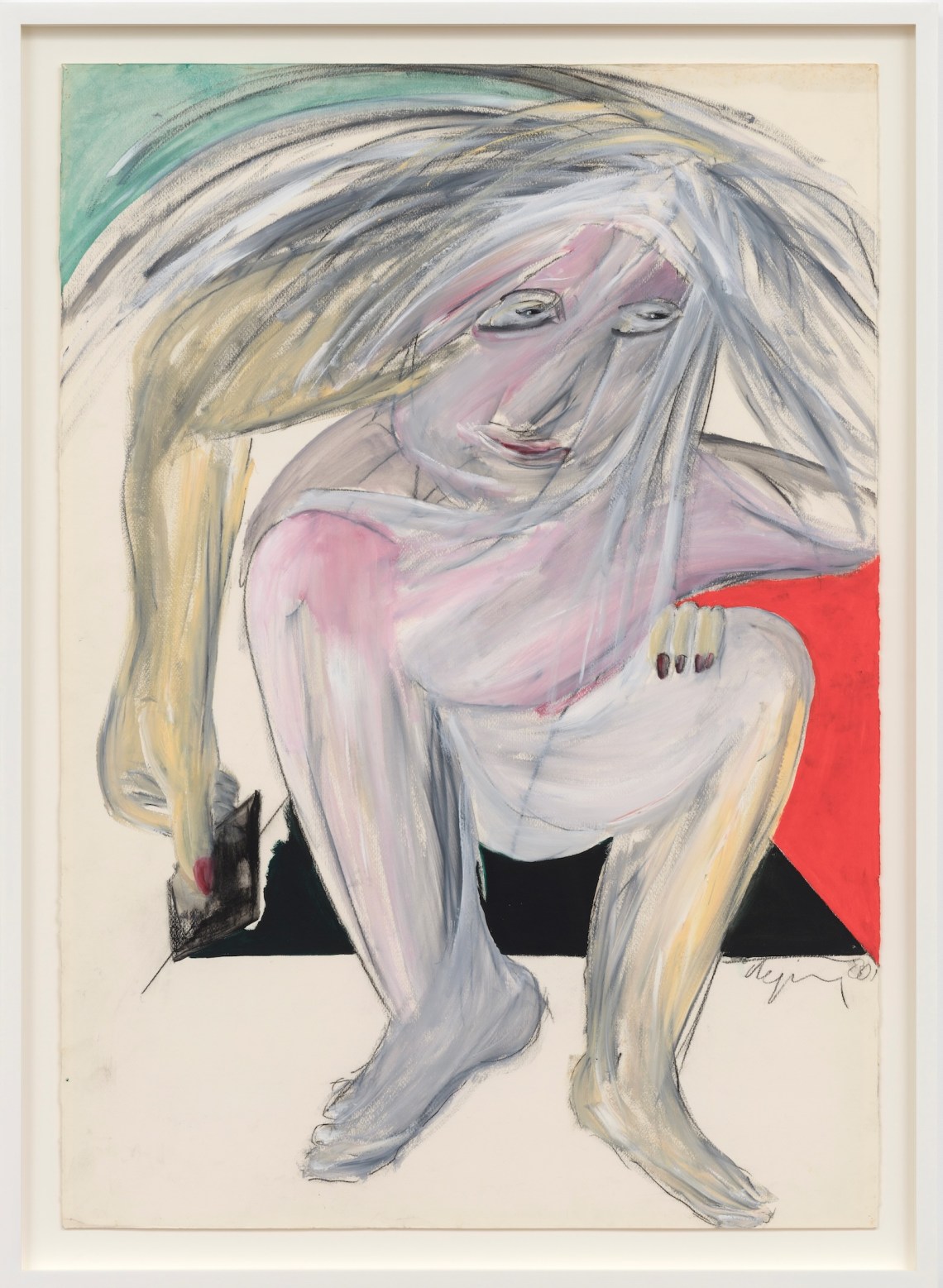

Am I wrong to wonder if the untitled orphan at Ortuzar (no title, 1981), a charcoal-and-crayon drawing on paper that belongs to neither the “Billiards” series nor “Série noire”—de Jong calls it a “free” work—is a self-portrait? It would be a good one: an aching confession that it’s impossible to work oneself out as a picture, but necessary still. The gray-haired woman is an aggravated pile of bent limbs, torso, and head. She chides herself with her left arm, or perhaps gives her heavy head a place to rest; with her right arm she reaches down with a shard-like implement and fills out the green-black floor. She looks in the other direction, far away from that dark trapezoid where art is made.