In 1988 Vaslav Nijinsky visited the dancer and choreographer Molissa Fenley in her New York City studio. He had been dead for nearly forty years—longer than Fenley had been alive. But as she worked on a wrenching, thirty-five-minute solo called State of Darkness, set to Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913), she couldn’t shake the feeling that he was in the room with her. Nijinsky had developed the original choreography for that rattling, cacophonous score; in his ballet, the ensemble performs a ritual sacrifice that culminates in the death of the Chosen One, a young woman who dances until her last breath. When Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes premiered the work, audiences famously rejected it; as Joan Acocella wrote in these pages, “the uproar in the theater was so great that the dancers could not hear the music.”1

Fenley choreographed State of Darkness after attending a Joffrey Ballet recreation of The Rite. In that version, which had premiered in Los Angeles in September 1987, more than twenty dancers ritualistically huddle and disperse on stage. In turns they stand upright—elongating their necks or marching on their tiptoes—and crumple toward the ground, kneeling and pounding it with clenched fists. Rarely is a dancer on her own; if she dusts up her heels or fixes her palms to her waist, there is most likely another performer at her side, or opposite her. The dancers form lines and clusters—and ultimately encircle the lone Chosen One.

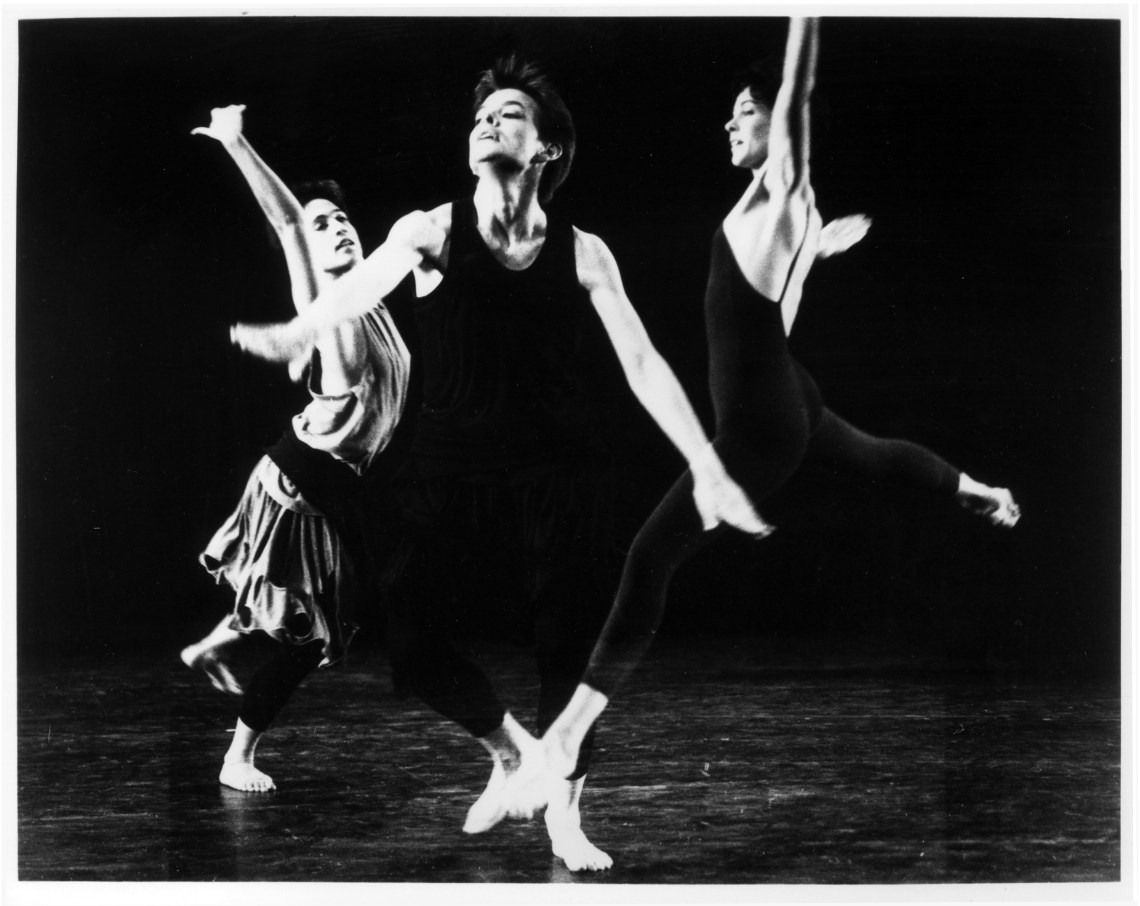

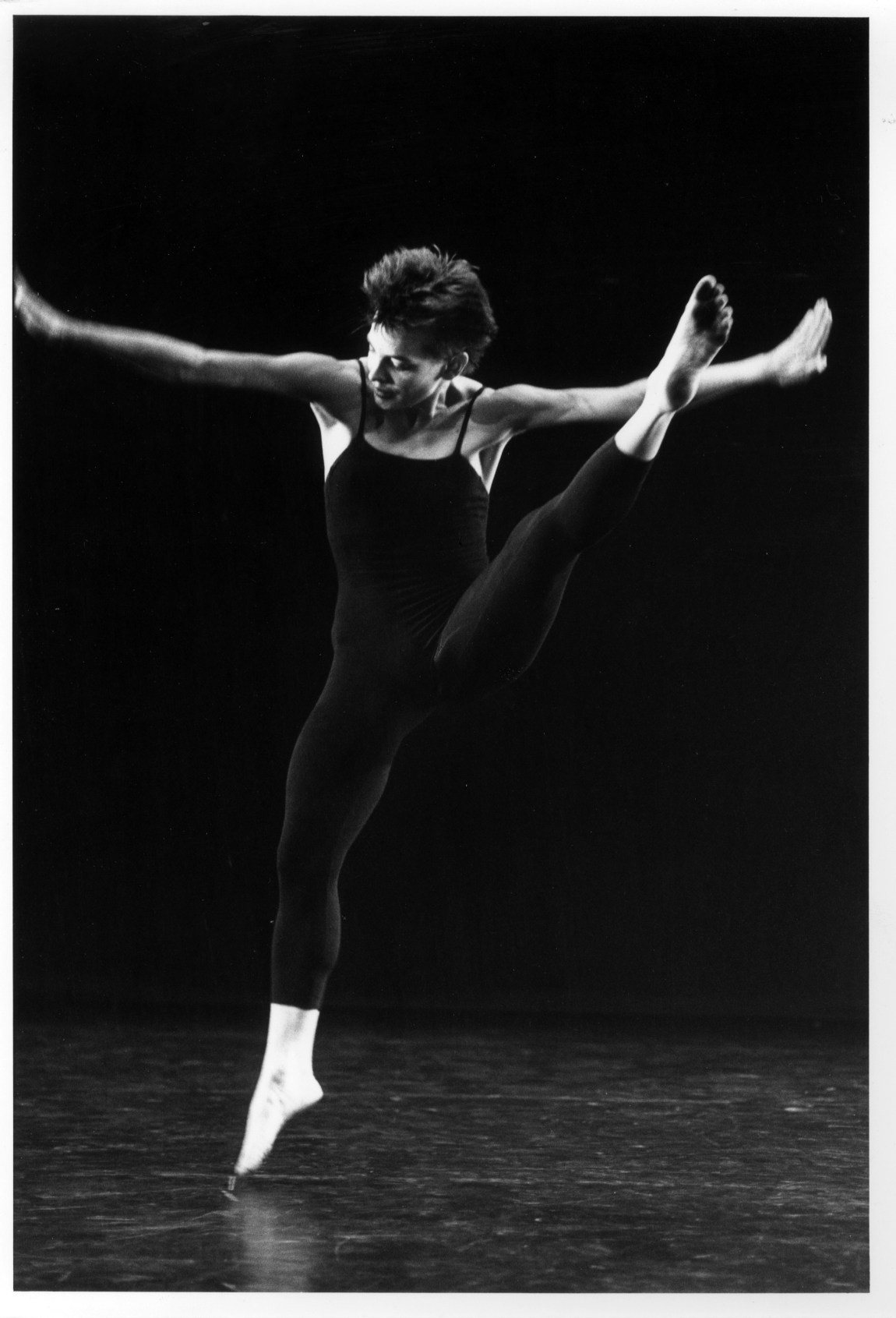

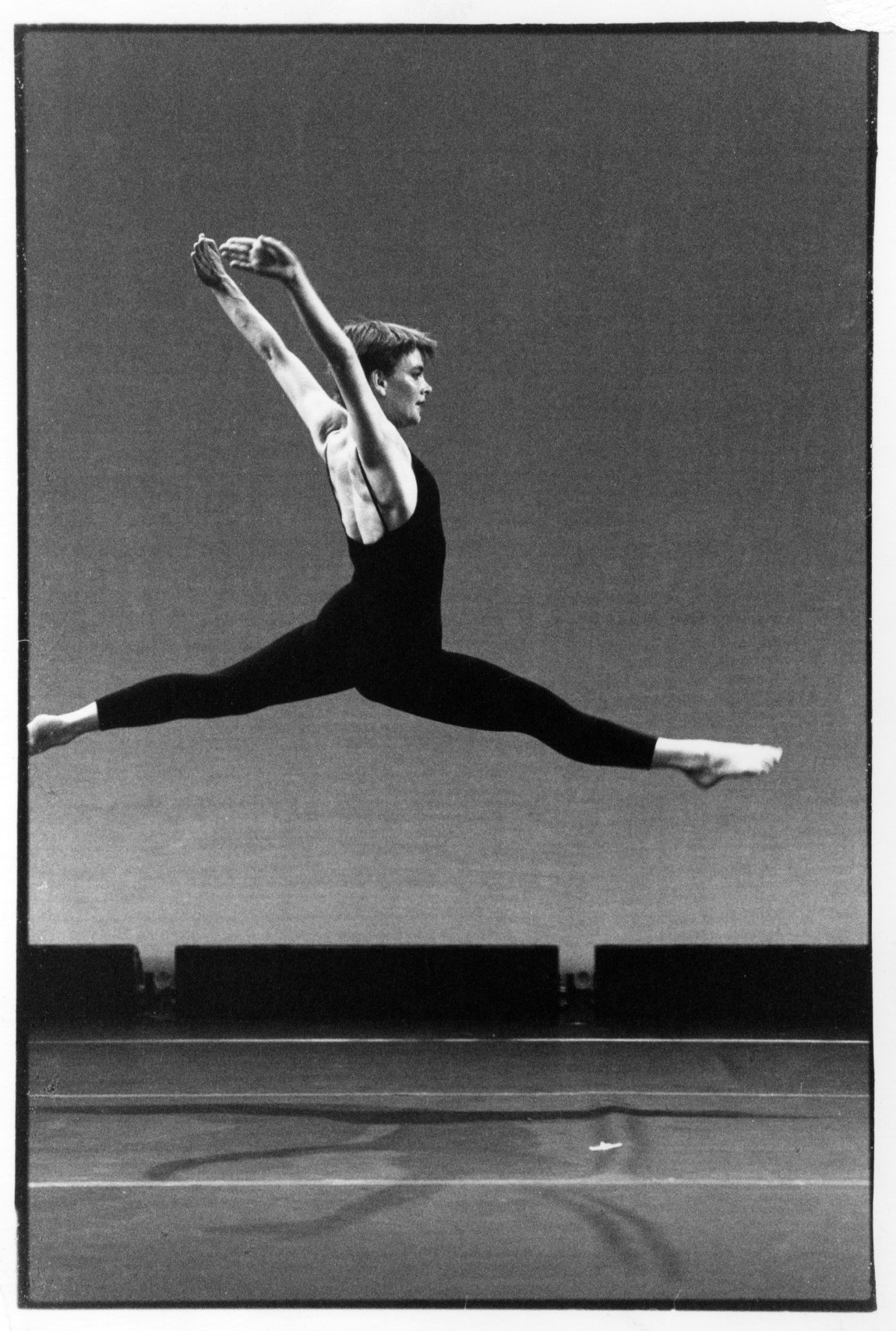

Fenley saw her solo, which premiered on June 20, 1988, at the American Dance Festival, as a response to Stravinsky’s score rather than the Joffrey performance. But watching that dance alongside the Joffrey one, it is as if she slips in and out of each Joffrey dancer’s role—the rival tribesman, the wise elder, the sacrificial woman—until she has subsumed the whole company. As she stalks a dimly lit expanse, dressed only in black leggings, her bare torso becomes its own kind of costume, constructed from ribs and skin; it ripples with every nimble, muscular gesture. One moment she might be galloping in a circle, the next shuffling on a diagonal with her palms outstretched in offering or sinking to one knee with her arms framing her face. In the solo’s closing seconds, she casts her final form: a “modern woman” who she sees as “intact, strong and alive.”

As Fenley recalled in Rhythm Field: The Dance of Molissa Fenley (2015), a volume that she coedited with Ann Murphy, Nijinsky had conveyed to her that he’d originally wanted The Rite to be a solo but “hadn’t been allowed to.” Fenley, though, was used to dancing alone. In 1987, a decade after founding Molissa Fenley and Company in New York City, she dissolved the group to focus on a solo career. In the work that followed, she might dash from the left wings to the right and back again in the time it took an audience member to stifle a sneeze; or, as in Bardo (1990), she might take thirty minutes to cross the stage, ten times the length of a typical ballet solo. (Reflecting on that dance in 2018, she reassured an interviewer that of course “dance things happened.”) It was as if she wanted to at once transcend her body and pack all of human experience into it. “I think it was never just me, Molissa Fenley, standing there,” she said in Rhythm Field. “It was me as some kind of iconographic representation of a solo human being.”

Then, in January 1995, on the opening night of her Joyce Theater season, she collapsed. She had been dancing yet another solo, adapted from a group work called Bridge of Dreams (1994), after it proved to be too expensive to fly the original performers from Berlin’s Deutsche Oper Ballet to New York City. The critic RoseLee Goldberg observed in Artforum that “the absence of the other dancers infused her solo with a poignant sense of loss, despite the richness of the choreography.” As Fenley lay on the stage floor, she recalled thinking, “they might as well shoot me, like a horse.” Ultimately, she recovered from the injury, later diagnosed as a torn anterior cruciate ligament. But it left a mark: by 1997 she had returned to ensemble work.

On the eve of her seventieth birthday this November, Fenley continues to choreograph and appear in new work. Her dances—more than ninety since 1978—are marked by a kinetic, spry athleticism in which a performer’s lower body forms a sturdy, pliable base for intricate arm movements. They also share a preoccupation with the lone artist and the company she keeps. Her group works often resemble kaleidoscopic solos in which dancers edge in and out of sync or splinter and fuse, reinforcing one another’s movements. Her solos, in turn, have the feel of shadowy duets, where the dancer beckons toward invisible partners or rests her hands on the shoulders of ghosts.

Advertisement

*

Molissa Fenley was born in 1954 in Las Vegas and raised in Ibadan and Lagos, Nigeria, where her father, an agriculture expert, worked with USAID. She spent two years in Spain earning a high school degree before enrolling at Mills College in Oakland, California, at the age of sixteen. Fenley credits these early years abroad as influences on her choreography—she admired the “endurance and stamina” of Yoruba dance and the strong arms and back that characterize flamenco. It was at Mills, though, that she finally stepped into a formal dance class, taught by Rebecca Fuller. As she described to Erin Carlisle Norton on Norton’s dance podcast, Movers & Shapers, the course catalog prompted students to dress in loose-fitting clothing. She showed up in her father’s painting smock; everyone else wore leotards and tights. As Fenley recalled, Fuller encouraged her students to develop their own movement styles and experiment with choreography: one couldn’t “wear technique like a coat,” Fenley recalled her saying. It was “inside the body.”

In 1975 Fenley moved to New York; two years later she launched Molissa Fenley and Company and sharpened her tympanic and propulsive style. In the forty-minute Energizer (1980), four dancers in colorful boiler suits windmill their arms, skip, twirl, and pivot on the half-step while pulsing in and out of a circle. New Yorkers who were, at the time, sweating through an aerobics craze—their days spent in fitness venues like the Vertical Club on the Upper East Side, their nights at the Joyce downtown—compared Fenley’s vigorous movement style to Jane Fonda’s.

The dance critic Arlene Croce went so far as to characterize Fenley as “a bad girl showing off.” But she has long kept a cool distance on stage, her eyes trained past the audience as if a gauzy scrim were erected between them. To her peers, even, she could be inscrutable. Elizabeth Streb, who was in the original cast of another group work called Mix (1979), described that piece—also danced in the round—as “fifty minutes of non-stop rhythmic variations” with “a beat and timing system that only Molissa fully understood.”

*

In recent years Fenley has been prolific in workshopping new dances and reworking pieces from her archive—including Mix, which she pared down in 2018 to a smooth twelve minutes. In the solitude of the pandemic, she turned back to State of Darkness, teaching it to seven acclaimed dancers: Jared Brown, Lloyd Knight, Sara Mearns, Shamel Pitts, Annique Roberts, Cassandra Trenary, and Michael Trusnovec. Fenley had first choreographed the dance soon after her friend Arnie Zane died of an AIDS-related illness, and a thick sense of mourning pervades her original choreography. For these renditions, which the Joyce livestreamed in October 2020, each dancer approaches the piece with the particularity of their training, but they all suggest the agony of confinement and the fragility of a body alone. In June 2021 six of those dancers would again perform State of Darkness at the Joyce—this time, in front of an audience.

For her latest engagement at Brooklyn’s Roulette Intermedium, Molissa Fenley and Company: From the Light, Between the Lamps, Fenley curated a series of new and recent pieces, plus a reimagined version of her 2004 group dance Lava Field. She appeared in most of the program, with the poise and fluidity she has maintained for nearly half a century. Joining her were three company members—Christiana Axelsen, Justin Lynch, and Timothy Ward—and Trusnovec and Knight. Trenary was also slated to perform but, due to an injury, joined the audience instead. Fenley’s longtime collaborator David Moodey oversaw the lighting design; Michael Ferrara and Enriqueta Somarriba played the piano for two respective pieces.

Fenley makes her entrance in the second dance of the program, Current Pieces #1–3 (2023), a series of three solos performed in turn by her, Axelsen, and Ward. In Fenley’s sequence, accompanied by Somarriba’s performance of a score by Vijay Iyer, she moves with graceful restraint, her leaps at times more like agile skips, her lunges like sturdy steps. Even the smallest gestures—a tilt of the wrist, a tap of the toe—seem to rumble from deep within. Her performance has the feel of a private rehearsal or a practiced ritual. Seated in the front row, at times within arm’s reach of her, I refrain from even the most discreet note-taking, not wanting to break whatever trance she’s in. But the trance pulls me in, too. She moves like a perpetual motion machine, without friction or inertia.

A transition that could pierce the moment only extends it: Axelsen swiftly twirls into view from the right wings, Fenley twirls off, and the younger dancer seamlessly begins Current Piece #2, a grounded, patient solo. Axelsen invests even the most complex movements with an air of familiarity and ease: she might pinwheel her arms around her upper body while—on an entirely different axis—swinging her legs in elegant, long lines. Ward, in Current Piece #3, adds a sense of instability and play to the triptych, halting a twirl at an unexpected angle or switching tempo mid-sprint across the stage.

Advertisement

Fenley’s ensemble works are often delicately staggered: dancers might perform the same jump slightly out of sync or run their hands over their scalps at a different pace—one reaching the nape of her neck before another. The late critic Sally Banes lingered on these “perceptual afterimages” in a 1980 essay, describing how Fenley would construct “paths through which dancers move successively, each one following the traces of the previous dancer.” Current Pieces #1–3, too, depend on these “afterimages,” with each sequence showing flickers of the solos that preceded it. The suite culminates with all three performers on stage together, moving downstage in sync—as if to start Current Piece #4—before slowing to an unexpected stillness. Had they not stopped, one wonders how many beats it would have taken them to split apart.

In the version of Lava Field (2004/2022) that Fenley staged at Roulette, featuring music by the electronic composer John Bischoff, she again plays with afterimages, this time blurring the form of the group dance; a quartet becomes two duets, or four solos. The piece begins with Fenley, Axelsen, and Ward forming a series of triangles with their limbs and the arrangements of their bodies on stage. Partway through, Lynch unexpectedly joins them and the geometry of the group changes from three edges to four. When the quartet jumps up and “falls” on their backs, each dancer settles at a different pace into a supine position; Fenley is the last to lay her head down. Later they seem to race one another, stomping downstage in a row and raising their arms like twisted goalposts. The dancers coalesce only when they clasp their hands to form a human knot or crumple in a pile; in these instances they move as one gnarled body.

*

During a visit to Italy in 2008 Fenley became interested in Cosmatesque mosaics: intricate, geometric inlays of glass and marble that adorned twelfth century Roman churches. She wondered what these medieval works of art, comprised of sharp-edged tiles arranged in a serpentine “ribbon pattern,” had “witnessed over the years.” They inspired Cosmati Variations #1–4, all set to twinkling, irregular scores by John Cage. Fenley has varied the number of people on stage for each dance, but the choreography never changes. As the number of dancers blooms, though, the performances take on new characteristics. Two people can, after all, draw only a line between them—six can form a circle.

The first four Cosmati Variations don’t appear in the Roulette program, but they are a prelude to Cosmati Variations #5 (2022). The first variation is precise and stately, with the dancers hinging their arms upward then downward, in a trapezoid formation—all in single, fast swoops. As the work progresses, it becomes more ritualistic: the performers crouch and crawl and sit upright, holding their hands above their heads as if supporting a heavy crown. The third movement is a relaxed, flowing recapitulation of the first; at one point the dancers come together in a circle, with their hands at the center like a maypole—something Fenley’s dancers also do during Etruscan Matisse/Blake (2023)—then disperse. The fourth installment restores a sense of order, with clean, long lines of movement.

The Roulette program opened with a duet version of Cosmati Variations #5, performed by Axelsen and Ward and set to Cage’s Third Construction (1941). It too is upright and angular, with Axelsen’s and Ward’s gestures staggered so that they move as if a tether between them has snapped, causing the dance to wobble. They begin upstage, standing next to each other, but as Axelsen turns in a circle, her arms framed around her head, Ward bolts forward past her. He doubles back within seconds, and for the rest of the dance they careen along their own tracks, at times drifting so close that they could touch, at others migrating toward opposite edges of the stage. Even when they fleetingly mirror or echo each other’s movements, they don’t linger. Ten minutes later, they reach their starting positions once more and clasp each other’s hands, completing a duet performed entirely in passing.

In contrast to the swerving choreography that anchors Cosmati Variations #5, De La Lumière, Entre les Lampes (2023) is performed primarily at center stage. This pair of duets, featuring a new score from Fenley’s longtime collaborator Philip Glass that Ferrara played live on piano, is elegant and courtly; at Roulette it also stood out as the only piece that would be fundamentally altered if a dancer were added or removed. On the night that I saw the program, Axelsen and Justin Lynch performed the first duet; Lynch performed the second with Knight, a principal in the Martha Graham Dance Company.

Knight and Lynch spend much of the dance within an arm’s reach of each other. They share a sense of care and conviviality, but they offer two complementary interpretations of Fenley’s style. Lynch’s movements are sweeping and elegant, and he can just as readily create one long, slanted line with his body as he can launch his limbs on different axes. Knight’s center of gravity is in his abdomen, and he is discerning in how high he lifts his legs or arches his back; he never lets his extremities run away from the rest of his body. A friend familiar with Knight’s career remarked on how he brought traces of the hulking, horned Minotaur from Graham’s Errand into the Maze (1947) to De La Lumière. He repurposed that strength and steadiness for a duet that was anything but combative. They end the dance face to face, each with a hand on the other’s shoulder.

*

When Fenley was regularly performing State of Darkness, a friend asked her how she could “climb that mountain each time.” Fenley was, she admitted, “addicted to it, to the challenge and great reward that dancing it brought.” She was also in good company on stage: “I summoned ‘my buddy Igor’ to help me make it through each performance, to withstand and transcend the demands of the dance.”

In the aftermath of Fenley’s 1995 injury, it became clear that she would need a more expansive definition of “dancing.” As part of her physical rehabilitation, she crafted Chair Dance (1995), a thorny solo that would ultimately serve to open a longer performance called Regions later that year. In it, she sits on a slatted wooden seat and bends over to touch her feet as if gingerly rousing them awake. Tangling and sprawling her body across the smooth surface of the chair for nearly ten minutes, she draws an abstract, haunting portrait of loss and its afterimages.

In a 2005 conversation with Tere O’Connor, reprinted in Rhythm Field, the pair linger on the absence of role models for aging dancers and choreographers. “If you are a visual artist,” O’Connor says, “you would look at Matisse, who did paper-cuts at the end and summed it all up!” Fenley has referred to Matisse directly at least twice in her work. The first instance was in 2019 for The Cut-Outs (Matisse), a hybrid spoken word and movement performance made in collaboration with the poet Bob Holman and the composer Keith Patchell, in celebration of the visual artist Elizabeth Murray. Onstage, Fenley arranged her body in a style reminiscent of Matisse’s cut-outs. It was a natural series of poses for her—upright and steady, with her arms outstretched at shoulder level or over her head and her wrists bent like punctuation.

Matisse returns as an influence in Etruscan Matisse/Blake, with a score from her longtime friend and collaborator, the electronic musician Ryuichi Sakamoto, who died in March 2023. The quintet opens with all five dancers in view, three in a cluster downstage left and level with the audience, two—Lynch and Trusnovec, a longtime Paul Taylor Dance Company principal and current codirector of dance at the Metropolitan Opera—on a raised platform to the right. Fenley leads the trio, with Axelsen and Ward each holding one of her hands while posing on one leg; later she leans back on the dancers, and they hold her in an embrace. She is often the first person to break into a new pose or angle her body in a new direction. All five slowly twirl, bow, and tap their toes; they have perfected the art of being ever so slightly out of sync. Their movements resemble abstract brushstrokes, every swoop of an arm or trace of a toe bringing new textures to the picture. They end the dance in a circle, their arms outstretched like an invitation.

The Roulette program ended with a meditative dance, set to birdsong: In the Garden (with Ryuichi) (2023), which the Fine Arts Center of the University of Massachusetts commissioned as part of its program “Sakamoto Blue Sky,” a tribute to the late composer. Fenley spreads four dancers across three levels, with Lynch and Ward—on different planes—turned away from the audience. It’s rare to see a dance in which half of the performers are facing the back of the stage, but thanks to Fenley’s careful arrangement, we don’t need to see their faces to share in their tenderness and intimacy. Fenley hovers on the middle platform, with Trusnovec at her side as a ballast. They sway as slowly as leaves on a spring tree. As imperceptible as the choreography may at times be, they never stop moving.