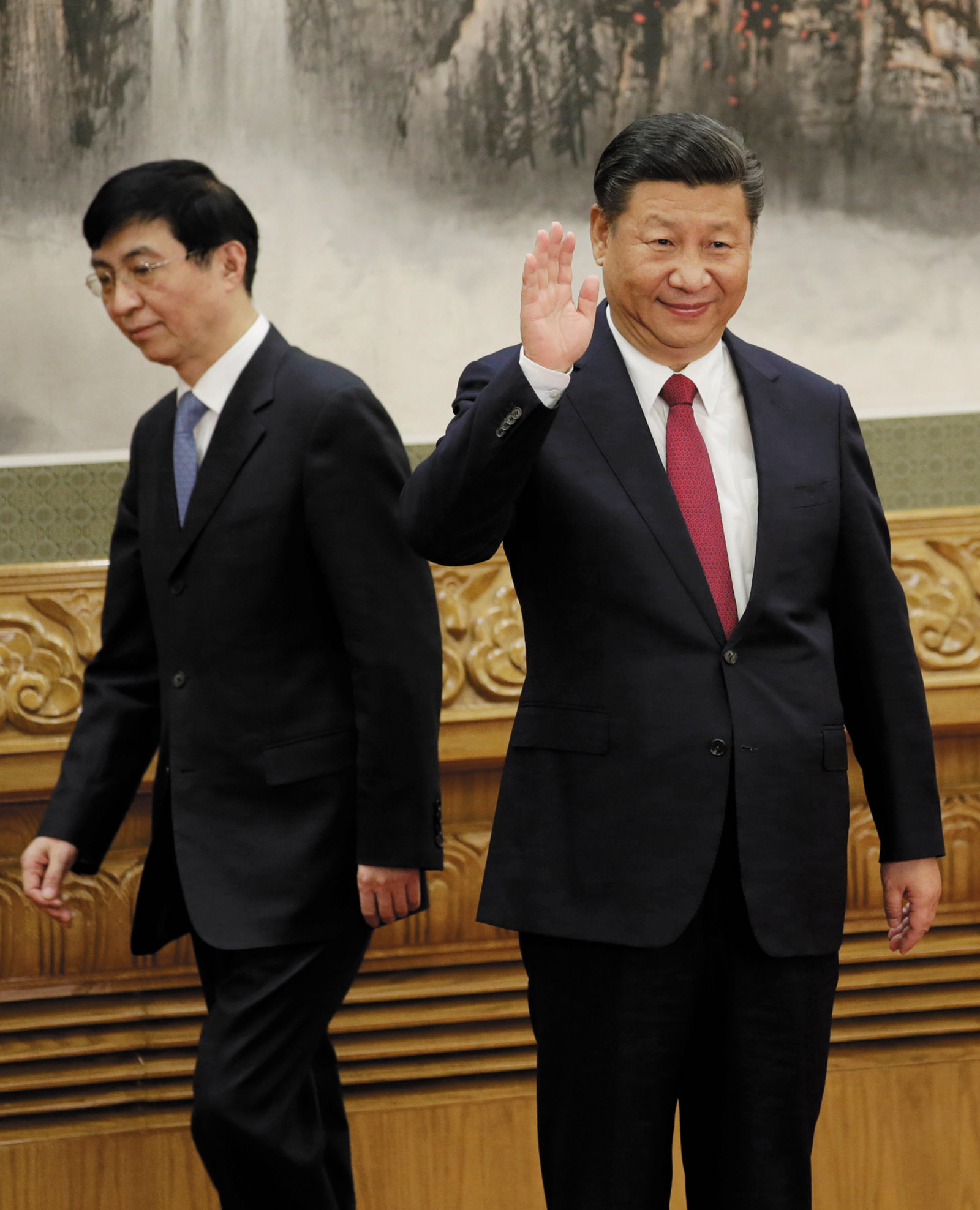

This fall, the Nineteenth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) gave proof that during his five years as general secretary Xi Jinping has become the most powerful leader of China since Mao Zedong died in 1976. Most observers, Chinese and foreign, who already knew this could only have been surprised at the manner in which it was displayed in public at the congress: in the choice of the new leadership team and the designation of an official ideology named for Xi.

The CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) consists of the party’s top leaders, and it currently has seven members. In the past, the PSC has been the location of ferocious struggles for power. Mao forced out two deputies who might have succeeded him: Liu Shaoqi, who was denied medical treatment when seriously ill, and Marshal Lin Biao, who was hounded into fleeing the country and died when his plane crashed in circumstances still shrouded in mystery. Even Deng Xiaoping sacked two general secretaries who had gone wobbly on him. Under Xi Jinping, a defeated rival who aspired to PSC membership was tried and imprisoned, and a powerful retiree from the Seventeenth PSC suffered the same fate. The PSC is the pinnacle of the CCP, but going up or down or simply standing still in the party’s upper reaches can be perilous. Fealty to the supreme leader is the surest guarantee of one’s position.

At each five-year congress the PSC is reconstituted. Retirement from it and other leading party bodies is roughly determined by a norm laid down by Deng, who hoped to have regular renewals of leadership and to avoid the spectacle of 1976, when Premier Zhou Enlai (seventy-seven), Marshal Zhu De (eighty-nine), and Chairman Mao (eighty-two) all died while still in office. Retirement by age seventy is now the target. The rule of thumb for the PSC has been that you should leave if you have reached sixty-eight at the time of a party congress, but there is a possibility of staying on if you are only sixty-seven. Five members of the eighteenth PSC retired as a result of this norm. Only Xi Jinping (sixty-four) and Premier Li Keqiang (sixty-two) were young enough to retain their positions. But before the recent congress, the Beijing rumor mill was wondering if a third member would be kept on despite the age barrier.

The top leadership of the CCP is chosen from—though not by—the twenty-five members of the Politburo, which is in turn chosen from, but again not by, the 376 new members and alternate members of the Central Committee (CC), who are chosen from (but not by) the 2,287 delegates to the party congress. In practice, the incumbent general secretary and his closest followers select the compositions of the leading bodies, especially the PSC, after some consultation and perhaps argument with peers and predecessors. So while the members of the Eighteenth PSC were chosen by Xi’s predecessors, the Nineteenth PSC is his creation. Since Xi loyalists headed the CC’s General Office, its nerve center, and the Organization Department, his capacity to detect and select trustworthy colleagues for the Nineteenth PSC was guaranteed.

The main concern of outside observers was whether or not the most trustworthy member of the outgoing PSC would be allowed to defy the age limit because of his importance to Xi.

During the past five years, Wang Qishan, sixty-nine, a long-term colleague of the general secretary’s, led the CCP’s Central Discipline Inspection Commission running Xi’s very determined, thorough, and much-heralded anticorruption campaign.1 According to the commission’s report to the recent congress, of the 74,880 nomenklatura officials—i.e., those whose careers were the CC’s responsibility—at the county level and above who were investigated after Wang took office in 2012, 280 were at the ministerial level or above. Over 35,000 corruption cases have been handed over to the judicial system for formal decision on punishment. Of the CCP’s almost 90 million members, 1,375,000 have been penalized for breaking party discipline, some doubtless for ignoring the party’s banqueting limit of “four dishes and a soup.”2

Xi was satisfied enough with the campaign to declare earlier this year that it had stopped corruption from spreading and had developed a “crushing momentum” against graft. So why did he not keep Wang on? The least likely speculation is that he was not strong enough to buck the age seventy rule. Xi is first above equals. Retaining Wang should not have been a heavy lift.

Was there anything in the charge of corruption leveled against Wang by the fugitive Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui from his luxury New York apartment? Guo had had close ties to a purged senior Chinese security official, and his allegations were much discussed by the Beijing chattering classes. But after he was visited twice in New York by Chinese security officials operating illegally on American territory, Guo failed to live up to his promise of revealing more at a press conference in New York during the Nineteenth Congress. Other rumors circulated. When Wang disappeared from view for several weeks earlier in the year, there was talk of cancer. Or was that only a face-saving excuse for his forced retirement? Then he turned up at some formal occasions looking much the same as ever, so that speculation ended.

Advertisement

A more likely possibility is that retaining Wang would send a signal that Xi intended to stay on as leader after the conclusion of his current second term. It has been widely noted that although Xi was given posts that marked him as the CCP’s future leader well in advance of his actual installation, he has ensured that the new leadership contains no obvious successor. So does he intend to emulate Mao and stay on into old age, which would be unprecedented in the post-Deng era?

If that is Xi’s long-term plan, then he is presumably not yet confident enough to make that final leap into immortality. So in place of Wang, he has promoted another close ally, Zhao Leji, director of the CC’s Organization Department, to the PSC, where he will take over the anti-corruption campaign. Alongside Zhao, Xi also promoted his principal loyalist in the CC, the head of the General Office, Li Zhanshu, who enters the PSC at number three in this hierarchically organized body.

The second-ranking member in the new PSC is Premier Li Keqiang, who held the same position in the previous committee. But in the past five years he has been humiliatingly overshadowed by President Xi, who has taken the chair of economic committees that Li should have led. The premier clearly lacks the self-confidence and forceful personality that enabled Premier Zhu Rongji to take charge of the economy when Jiang Zemin was general secretary. Li would be better suited to the one remaining high-ranking but ceremonial post, the vice-presidency, which will be decided in the spring, though some think Xi is holding that office for Wang Qishan. Li’s fate was not a topic of the Beijing rumor mill because his subordinate role is widely perceived. One cruel comment from a Chinese intellectual was: “Does it matter?”

While Wang Qishan’s fate was the focus of much speculation, the most intriguing change in the membership of the PSC was the promotion into it of Wang Huning (no relation), who was the first genuine intellectual to gain this honor. Wang is from Shanghai, where he was a graduate student and later a very young professor at the prestigious Fudan University. After receiving recommendations from Shanghai party leaders, Wang was recruited by then general secretary Jiang Zemin for the Central Policy Research Office.

By the end of Jiang’s term in 2002, Wang had helped him devise his theory of “three represents” and had risen to become director of the office. He was retained by the incoming general secretary, Hu Jintao, who recognized his talent and whom he accompanied on foreign trips, and Wang helped write Hu’s theory of the scientific outlook on development. Both the theory of three represents and the scientific outlook on development have become official party doctrine. After Hu retired, Wang made himself indispensable to Xi, joining him too on international trips. He has now been appointed head of the party’s central secretariat in addition to his PSC membership. Yet unlike most other senior leaders, he has never run a province or a government department.

Wang is not so much an opportunist as a Kissinger-type intellectual whose wisdom every new leader feels he has to exploit. In his academic days he published widely. A six-month visit to the US resulted in a book, America Against America, that probed the contradictions within American society. One Chinese bookseller is taking advantage of Wang’s meteoric rise to offer a copy of his 1995 diary/memoir, A Political Life (Zhengzhide rensheng), published on the eve of his move to Beijing, for 11,888 yuan (almost $1,800). One of the themes Wang advocated in his writings was “new authoritarianism”; his emphasis on the need for strong leadership and his aversion to introducing Western democracy to China doubtless helped endear him to Xi.3

At number four in the new pecking order, just above Wang Huning, is Wang Yang, a very different kind of man. From 2007 to 2012, Wang Yang ran China’s richest province, Guangdong, on the border with Hong Kong, gaining a reputation as a determined and innovative economic reformer. He was widely praised for peacefully resolving an uprising by villagers in Wukan against party cadres who had sold their land from under them, though his settlement was abandoned under his successor. Already in the Politburo when Xi came to power in 2012, Wang was transferred from his provincial post to the central government as a vice-premier overseeing parts of the economy.

Advertisement

In his new position, Wang Yang created a sensation among Western journalists in July 2013 when he met Treasury Secretary Jack Lew in Washington at the annual economic summit between the US and China. Wang compared the Sino-US relationship to a marriage with both parties building trust and cooperation. “In China when we say a pair of new people, we mean a newlywed couple. Although US law does permit marriage between two men, I don’t think this is what Jacob or I actually want. We cannot have a divorce the way Wendi and Rupert Murdoch just had…. For that, it would be too big a price to pay.”4

Xi Jinping does not seem the kind of leader who would appreciate Wang’s sense of humor. But if Xi gives him some room, Wang may be the man to arrange a successful marriage between state-owned enterprises and the private sector, which would enable Xi to see his long-promised but so far undelivered economic reform program come to fruition. Shortly after his elevation to the PSC, Wang wrote in the official newspaper, People’s Daily, that China should improve the business environment for foreign investors and widen access to its services sector. In a further gesture toward foreign businessmen, he stated that China should protect intellectual property, should not require technology transfer as a condition of gaining market access, and should treat domestic and foreign firms equally in government procurement. Of course, such words have been uttered before by Chinese spokesmen, and Western observers are understandably skeptical that Wang will actually make it easier for foreign businesses to operate in China. On the other hand, it is difficult to imagine Xi allowing him to make such a statement if it meant as little today as it did in the past.

The lowest-ranked member of the new PSC is Shanghai party secretary Han Zheng. Some say his presence on the committee, along with Wang Huning’s, was a concession to former general secretary Jiang Zemin, who controlled a faction in Shanghai—the Shanghai “gang”—where he was once party secretary, while Li Keqiang and Wang Yang were concessions to the Youth League faction of Hu Jintao, who had once been first secretary of the Youth League. Although factional connections go deep in Chinese politics, it seems unlikely that Xi Jinping could establish his supremacy so clearly at the Nineteenth Congress and still have to accept colleagues allied with his predecessors. Before the congress, for instance, Xi took decisive institutional moves against the Youth League, once the powerful junior partner of the CCP; unprecedentedly, its party secretary was not even allowed to be a congress delegate.

In case any of his new colleagues did not understand who was boss, Xi reemphasized his commanding position at the first meeting of the Politburo, at which it was decreed that all members had to write reports to the general secretary every year detailing their activities. It seems more likely that Han Zheng is in the PSC because Shanghai, as the biggest and richest city in China, deserves representation at the top, but we shall know more when we see how Xi deploys him.

Even more impressive than the team that Xi has put together to help him lead China is the additional status he has conferred upon himself. Today in China, the CCP general secretary is also chairman of the party’s Military Affairs Commission and president of the People’s Republic. While the presidency gives Chinese leaders equal status in diplomatic encounters with foreign leaders, the chairmanship underlines the fact that the People’s Liberation Army belongs to the party, not the nation, as armies do almost everywhere else in the world. No Chinese leader is likely to ignore Mao’s famous dictum: “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” At the beginning of his first term, in addition to taking on the leadership of powerful economic committees, Xi also made himself head of committees on national security and foreign affairs.

During the past five years, Xi was accorded two additional honors. He was declared the “core” of the party’s leadership, a seemingly redundant title except for its historical resonance. In 1997, Jiang Zemin was seventy-one and was challenged to retire by an even older contemporary. But it was pointed out by a surviving party elder that Deng Xiaoping had granted Jiang the title, and that this meant he could not retire just then. The challenger had to go, but Jiang served another term as general secretary, retiring only in 2002, when he was seventy-six. This could be a precedent that Xi will exploit in due course.

Xi was also named commander-in-chief, a title that only Zhu De, Mao’s military alter ego during the revolution, could claim. Presumably it was meant to show that Xi, who inspected the parade commemorating the ninetieth anniversary of the PLA this year in military fatigues, was not just a civilian chairing the generals in the Military Affairs Commission but a soldier too, ready to command troops in battle. How the generals on the Military Affairs Commission have taken this is uncertain,5 but some observers argue that Xi’s sweeping restructuring of the military over the past two years will ensure the loyalty of newly promoted generals.6

But both these titles were dwarfed by the reference to Xi Jinping in the new party constitution passed at the congress:

The Communist Party of China uses Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, the Scientific Outlook on Development, and Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era as its guides to action.

With those few words, Xi leapt over Deng, whose opening up and reform were crucial to China’s spectacular economic growth over the past thirty-five years, but who only had a theory; and over his two predecessors, who had a theory or an outlook but whose names are never listed beside them. Xi is now up there with Mao, his most daring claim thus far. As Mao did, he likes to lace his speeches with quotations from the Chinese classics, though he uses them to underline points of current policy, not to bewilder his less well-read colleagues, which Mao seemed to delight in doing.

An enterprising Chinese journalist has sifted through Xi’s speeches and collected examples of this practice.7 A quotation from The Analects in which Confucius answers one of his pupils that “if you were to lead the people correctly, who would not be rectified?” enables Xi to urge party leaders to act as exemplars. Stressing the need for many talented and able officials in order for China to achieve his aim of national rejuvenation, he quoted The Book of Poetry, an anthology of lyrics from the eleventh to the seventh centuries BCE: “Admirable are the many officers born in this royal kingdom. The royal kingdom is able to produce them, the supporters of [the House of] Zhou. Numerous is the array of officers, and by them King Wen enjoys his repose.” Xi, commenting, said that to “found a state that can last for centuries, talent is the key.”

But leaving aside the classical embellishments, what does Xi’s Thought stand for? “Socialism with Chinese characteristics” is a phrase that has been around ever since the beginning of the reform era in 1979. Baldly put, it has meant that China’s leaders will adopt almost any policy that will produce economic growth, but they will still call it socialism. What’s new is the “New Era,” which presumably starts now, or perhaps it began with Xi’s accession five years ago. Therefore one has to study his pronouncements on the governance of China.

Fortunately, the Chinese propaganda authorities, who have encouraged the ever-burgeoning cult of Xi—a recent news broadcast from China’s central TV station opened with over four minutes of nothing but people applauding Xi—have published a book of his speeches in Chinese and foreign languages on the wide variety of topics that a general secretary who insists on controlling everything has to cover. The diligence of Xi’s flacks to ensure that his pronouncements are widely available is commendable, though mind-numbing titles might put off a foreign reader: “Explanatory Notes to the ‘Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Continuing the Reform.’” In this case Xi, on behalf of the Politburo, is explaining a “CC decision” to the CC, which is indicative of where the decision was actually made.8

This decision was an important milestone under Xi’s leadership, but it also exposed problems in his strategy. Xi explained that he and two other PSC members were responsible for the drafting of the decision, but the seven-month-long process involved consultations with national and provincial leaders, retired party officials, the heads of the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, and various non-CCP notables, as well as three review meetings by the PSC and two by the Politburo. A primary purpose was to give the market an enhanced part in the economy: “The market plays a decisive role in allocating resources, but it is not the sole actor in this regard.”9

And there was the rub that over the succeeding four years Xi’s team failed to transform China from an economy that depended on exports to a domestic one that depended on consumption. Xi is wedded to state-owned enterprises as the bulwark of a socialist economy and nervous about an untamed free market. The bursting of the Shanghai stock market bubble in 2015 must have been a grave shock.

But in his three-and-a-half-hour marathon speech to the Nineteenth Congress, Xi was relentlessly upbeat. Problems were listed, shortcomings admitted, but breakthroughs had been made in important areas and general “frameworks,” in Xi’s phrase, for reform had been established due to the launch of 1,500 reform measures. China was fully committed to building a “moderately prosperous society in all respects” by 2020, he said, in time for the CCP’s centenary in 2021. Between 2020 and 2035, China is to emerge as a global leader in innovation, its people will have more comfortable lives, and the middle-income level will have expanded considerably. The rights of the people will be protected, and social etiquette and civility will be significantly enhanced, i.e., the Chinese will be nicer to each other.

The second stage of Xi’s plan will last from 2035 to midcentury, in time for the centenary of the Chinese People’s Republic in 2049, and will see China become a great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful, a global leader that has achieved national strength and international influence. In short, the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and the flowering of the Chinese dream, a vague notion of restoring the greatness of China’s most glorious dynasties, which Xi has made his overarching aim since coming into power, will have been realized. And to achieve all this, the party leadership must be upheld and the strength of the party increased. Thus when Xi talks of the rule of law he does not mean the party will be subject to it, just as “democracy” for him does not imply any threat to China’s Leninist system of government.

In his speech, Xi revealed some of the steely patriotism that clearly underlies his smiling and unthreatening public persona:

The Chinese nation is a great nation; it has been through hardships and adversity but remains indomitable. The Chinese people are a great people; they are industrious and brave; and they never pause in the pursuit of progress. The Communist Party of China is a great party; it has the courage to fight and the mettle to win.

The wheels of history roll on; the tides of the times are vast and mighty. History looks kindly on those with resolve, with drive and ambition, and with plenty of guts; it won’t wait for the hesitant, the apathetic, or those shy of a challenge.10

And in this brave new era, China will be “moving closer to center stage,” in case anyone had not noticed.

This Issue

January 18, 2018

Damage Bigly

Divine Lust

This Land Is Our Land

-

1

See Andrew J. Nathan, “China: The Struggle at the Top,” The New York Review, February 9, 2017. ↩

-

2

Some sources have suggested that the meal might include braised chicken, stir-fried pork, a stew, fried garlic shoots with chrysanthemum stems, and pork and melon soup. ↩

-

3

Zhengzhide rensheng, pp. 129–135. I am grateful to Rudolf Wagner for pinpointing this segment of Wang’s book on the Internet. ↩

-

4

“US-China Relationship Like a (Straight) Marriage—China’s Wang,” Reuters, July 10, 2013. ↩

-

5

On similar occasions in the past, Xi’s predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao wore well-tailored Mao suits. ↩

-

6

Bo Zhiyue, China’s Political Dynamics under Xi Jinping (World Scientific, 2016), pp. 75–77. ↩

-

7

Zhang Fengzhi, Xi Jinping: How to Read Confucius and Other Chinese Classical Thinkers (CN Times Books, 2015). ↩

-

8

Xi Jinping, The Governance of China (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2014), p. 76. ↩

-

9

Xi, The Governance of China, p. 85. ↩

-

10

From the officially translated text issued in Beijing. There is an echo here of the young Mao, who wrote in 1919: “The time has come! The great tide in the world is rolling ever more impetuously!… He who conforms to it shall survive, he who resists it shall perish.” Quoted in Stuart R. Schram, The Political Thought of Mao Tse-tung (Pelican, 1969), p. 163. ↩