Early in the campaign Barry Goldwater established a firm image of himself as predictably unpredictable: no one can tell where the audacious veerings and swoopings of his mind will take him, what bizarre new sallies he will launch, what vast intellectual retreats he will find it necessary to undertake without acknowledging that he has budged an inch.

One stands in bewilderment before such a mentality. The temptation to explain the man simply as an outrageous opportunist must be resisted. There is, and indeed should be, an element of the opportunist in every political man, and Goldwater is no exception. His opportunism has grown as he has moved closer to the grand prize. But his earlier voting record, taken as a whole, is not the record of an opportunist but of a man of principle, whatever you think of his principles.

Nor is it quite satisfactory to settle for the proposition that he is not as alert or informed intellectually as we are accustomed to expect our major political figures to be. There must be many men active in our public life who are no smarter than Goldwater but who do not share his lust for banalities and absurdities. Indeed, one of Goldwater’s problems is that his mind is not only more vigorous but also more pretentious than the ordinary. He yearns for profundity, and is so intent upon elaborating his ideas that he has written, or at least signed, two books that have increased his vulnerability. Much of his difficulty rests, I believe, upon the fact that his serious political education began only recently, and he has been in the unenviable position of having to conduct it in public.

It is no simple thing to account for the development and the prominence of a mind so out of key with the basic tonalities of our political life, and it would take a soothsayer to tell us what we can expect of it in the future. However, Goldwater’s present difficulties in winning broader acceptance, even among the moderate voters in his own party, may blind us to the fact that up to the point of his nomination at the Cow Palace his impulsive and contradictory pronouncements were a part of his stock in trade and they were selling. His main problem now is that it is hard to create still another new image of himself. It is possible, I believe, to discern three overlapping but fairly distinct Barry Goldwaters. The chronological lines that separate them are by no means absolute, and the earlier Goldwaters can still be seen slightly below the surface of the latest Goldwater. Still, for the purpose of understanding his career, they can be roughly distinguished.

I

Goldwater I is the original, the native, the impulsive Goldwater, as he was raised in Arizona and as he regularly expressed himself up to about a year ago, before he mounted his final campaign for the nomination. To understand him one must think of the political and social atmosphere of the Southwest, where the raw views of the new millionaires count for much more than they do in other parts of the country, a region where the reforms of the New Deal, now a generation behind us, are still acutely controversial. Imagine a charming, vigorous, basically apolitical man somehow drawn out of this atmosphere into political affairs. Endowed with an active, though largely untutored, mind, he is attracted by the resonances of deep-sounding ideas, and he superimposes upon the brash conservatism of the country-club locker rooms some hasty acquaintance with the notions of our ultraconservative highbrows. Grant that you begin with a man who has a keen taste for combat—political, moral, or military—and who looks upon the necessity of countering the dominant liberal philosophy of the country as a welcome challenge to his manliness and independence. Here you have the first Goldwater, who charmed the right-wing enthusiasts in the Republican party, and whose ardent campaigning among them built up the strong cult that has made him what he is today.

Now imagine the uninhibited psychological mood in which the ideas of Goldwater I are formed and expressed. First, there is the remoteness from actual administrative, and even from legislative, responsibility; as Senator, Goldwater does not become responsible for any major positive legislation, is never thrown into a position in which he must carefully weigh the relation between legislative aims and social realities. His entire intellectual stance puts him into a negative relation to the legislative process. His contribution as a senator is not to sit, as for example, Robert A. Taft did, with other senators in committee trying to iron out the intricacies of pending legislation: it is simply to vote No. In fact, the greatest part of his political life during the years of his senatorial prominence is to make speeches—hundreds of them—before audiences already largely or entirely sympathetic to his message. He is an ideologue and a prophet; he has little need to persuade, only to exhort, and like most exhorters he hypnotizes himself with his own repetition. He luxuriates in saying what he truly believes, without having to weigh his words, before receptive and enthusiastic audiences. In the process, he makes friends and admirers throughout the country. As yet he does not really expect to be nominated for the Presidency, much less to be President; so it is hardly necessary for him to think very much about what his ideas would actually involve if they were the ideas of the man in the White House.

Advertisement

Goldwater I, then, spoke freely. “I of the world thinks about the United States as long as we keep strong militarily.” “We should, I believe, announce in no uncertain terms that we are against disarmament.” For a time he favored withdrawing recognition from the Soviets. He found the U. N. “unworkable,” and urged that we “quit wasting our money on it.” He denied that there is “such a thing as peaceful coexistence.” He thought that Khrushchev’s visit to the United States was the consequence of “a craven fear of death” that had entered the American consciousness. He attacked Eisenhower’s 1957 budget as “a betrayal of the people’s trust,” and his administration as a “dime store New Deal,” urged that the government sell TVA “even if they only get one dollar for it.”

II

If Goldwater I represents the Goldwater id, Goldwater II represents the Goldwater ego, aware of the eyes of a larger world, and now making certain more rational calculations about what a major public figure ought to be saying. Goldwater II became increasingly evident about a year ago. Goldwater is here no longer the provincial prophet but an increasingly powerful party figure about to make a sustained bid for the presidential nomination, and concerned about what his ideas might sound like to a larger national audience. While he is not yet making statements that risk alienating his true believers, he is beginning to realize that some of his past utterances have discredited him. He states that he is going to process his past statements through a computer so that he will have greater mastery over what he has said. (This in itself marks a historic moment in our politics.) His statements are now often set forth within the framework of a kind of craftsmanlike equivocation.

Now it is not withdrawal of recognition of the Soviet that is demanded but the use of the threat to withdraw recognition as a means to win bargaining concessions. Withdrawal from the U.N. is no longer urged—except if Red China should be admitted. In the New Hampshire campaign Goldwater declares: “We must stay in the United Nations, but we must improve it.” Again, in the same campaign, he insists that the statement that he is against social security is a “flagrant lie,” but adds that he does believe that by 1970 social security beneficiaries “will be asking questions such as whether better programs couldn’t be bought on the private market.” More recently he has suggested threatening the Red Chinese with a show of force if they continued to supply the Viet Cong guerrillas, but he quickly added: “I’m not really recommending this but it might not be an impossible idea.”

Goldwater II’s increasingly experimental way with ideas may be explained in part by his previous business experience. While he has never had any administrative or legislative responsibility, he was a successful businessman in Arizona, and much of his success rested on his capacities as a merchandiser. He understands the problems of salesmanship, and appears to have transferred the salesman’s pragmatic promotional techniques to politics. He once said that his political don’t give a tinker’s dam what the rest role was largely that of “a salesman of ideas,” and he spontaneously used the same comparison shortly after his nomination when he said in an interview that he hoped the campaign would prove him “a better salesman” than President Johnson. Now there is a certain innocuous tentativeness about the tricks of salesmanship—like the famous “antsy pants” so successfully marketed by the Goldwater stores—and it may be both charitable and accurate to look upon Goldwater’s sudden suggestions that the Marines be sent to turn on the water at Guantanamo or that the jungle in Vietnam be defoliated by nuclear devices as the experimental gestures of a man who is feeling his way into a new and larger market of public opinion. Aggressive though such proposals sound, they are put forth in an experimental way, and may be withdrawn and discarded if they do not arouse much consumer interest.

Advertisement

If one bears in mind that Goldwater represents a very special minority point of view, which is not even preponderant in his own party, one must grant that in capturing the Republican party he has turned in a remarkable political performance, and that Goldwater I and Goldwater II have thus far served him well. Of course, he was helped by a series of poilitical accidents: the divorce and remarriage of Rockefeller crippled a formidable antagonist; the assassination of Kennedy and the ensuing overwhelming popularity of Johnson caused other candidates to hang back, looking to 1968 rather than 1964; an unusually large field of possible moderate candidates spread disunity among the opposition; even the fact that his prospects were greatly underrated after the New Hampshire primary worked in the end to his advantage. But what must not be discounted—quite aside from the Senator’s own charisma—is that his arduous speech-making labors of the previous four years have paid off partly in putting innumerable Republican workers around the country in his debt, but largely in recruiting and inspiring a corps of fanatical workers such as no other candidate could mobilize. Above all, up to the moment of the convention in San Francisco, his equivocations and contradictions had done him more good than harm. The ideas of Goldwater I brought him his army of true believers, and the softer and more dazzling dialectics of Goldwater II suggested that he was not really in fact one of the cranks but a genuine conservative leader flexible enough to conduct a winning campaign.

III

The situation that prevailed after the convention demanded the appearance of one more Goldwater. Too many fangs had been bared in the Cow Palace and a very bad impression had been made. The national press was singularly hostile, and it is easy to believe that the Senator was wounded by his failure, even with a major-party mantle over his shoulders, to attain the full credentials of respectability. The party was still badly divided, and the extremist label seemed to be sticking. It had become necessary to make the conciliatory gestures so noticably lacking at the Cow Palace.

Hence, at the Hershey conference, Goldwater III, an entirely new creation, was unveiled. Goldwater III is the statesman-in-the-making, building party unity and seeking the support of those middle-ground voters without whom his chances for the presidency are negligible. At the Hershey conference, Goldwater not only said most of the healing and conciliatory things that were missing from his acceptance address, but even added some gratuitous concessions. He promised to return to the “proven policy of peace through strength which was the hallmark of the Eisenhower years,” and to make no appointments to the offices of Secretary of Defense or Secretary of State or other critical national security posts without first discussing his plans with Eisenhower, Nixon, and other “experienced leaders seasoned in world affairs.” He reiterated his support for the U.N. and his determination to make it “a more effective instrument for peace among nations.” He affirmed his support “for perhaps the one-millionth time” for the Social Security system, expressed a desire to see it strengthened, and soon afterward said he would vote to extend it. He pledged faithful execution of the Civil Rights Act. He said that he wanted to read no one out of the party, and wanted no support from extremists.

Having said all this, Goldwater told reporters: “This is no conciliatory speech at all. It merely reaffirms what I’ve been saying throughout the campaign. Now sometimes it hasn’t gotten through quite clear. I don’t know why but there are reasons, I suppose.” One can readily understand the caution expressed by Nelson Rockefeller, when asked by reporters whether Goldwater’s statement represented a shift of position. “I think, said Rockefeller, “it’s his position as of today on these issues.”

Reporters who seem to know say that there is regret in the Goldwater high command that some of these conciliatory things were not said at the Cow Palace. By letting a few weeks intervene, the image of the extremist Goldwater became fixed. To have struck the soft note earlier would have been more in the spirit of our major party politics. But one must not fail to recall that the forces that raised Goldwater to his present eminence do not share the representative major-party ethos. For Goldwater to have been soft and conciliatory at the Cow Palace would have stunned his zealots in their seats and sent them away in a state of confusion. In the nation at large the effects of such a gesture might have been good, but it would have blunted the “extremist” image only to create, at the moment of triumph, new and more urgent uncertainties about where Goldwater stands.

As it is, Goldwater’s true believers can now treasure the notion that Goldwater III is a false-face created only for the purposes of the campaign, and that in his heart of hearts Barry still belongs to them. I believe that they are right in more than one sense. It is not merely that Goldwater’s pulse seems to quicken when he is taking an avantgarde right-wing line, but that the hard work and the money required to nominate him were provided by zealots of a very advanced persuasion. Moderate Republicans by the millions may in the end swallow their reservations and give their votes to Goldwater, but it is only the true believers who will go on giving their hearts and their purses. If he is to be elected, or renominated in 1968, it will be only they who can do it for him.

It is their strategic importance, and the overheated ideological character of their politics, which suggest that the usual rules of political conduct are likely to be suspended. In the ordinary course of our pragmatic, non-ideological politics, party workers are moved by the desire to find a winner, to get and keep office, to frame programs on which they can generally agree, to use these programs to satisfy the major interests in our society, and to make an effort to help solve its most acute problems. If they find that they have chosen a loser, they are quick to start looking for another leader; if they see that their program is out of touch with the basic realities, they grope their way toward a new one.

It is not so with Goldwater’s true believers. They seem more moved by the impulse to dominate the party than to win the country, more concerned to express resentments and punish “traitors,” to justify a set of values and assert grandiose, militant visions than to solve any actual problems of state. This is one reason why they seem so little troubled by Goldwater’s self-contradictory policy pronouncements. By the same token, it is not easy to predict that they will respond in the customary way to the reality of defeat. Where the conventional party worker looks upon defeat as a spur to rethink his commitments and his strategy, they are likely to see it primarily as additional evidence of the conspiracy by which they think they have been surrounded all along, and to conclude that they must redouble their efforts.

IV

The one salient thread of consistency amid Goldwater’s self-contradictions is the most alarming aspect of his thinking, and that is his conception of the cold war. So far as I know, he has steadfastly repudiated the idea of peaceful coexistence. He sees the cold war as a series of relentless confrontations between ourselves and the Communists on various fronts throughout the world. He holds that if we maintain superior strength we can emerge victorious from all these confrontations; that in time the whole Communist world (which should be treated uniformly as a bloc whatever its apparent internal differences) will crack under the stress of repeated defeats; that we need not fear the likelihood that impending defeat will precipitate a counter-strike that could lead to nuclear war.

Nothing could be more disingenuous than Goldwater’s attempt at Hershey to suggest that his conception of the cold war and his policies toward it are in the Eisenhower tradition of “peace through strength,” as Goldwater calls it. In fact Eisenhower’s policy, like that of Kennedy and Johnson, was basically the cautious one of détente and accommodation. What appeals to Goldwater in Eisenhower’s record is not the basic circumspection that governed it but the occasional risky strokes that Eisenhower felt it necessary to make, like his move into Lebanon and his policy toward the offshore islands. Nothing could be more remote, for example, from Eisenhower’s cautious abstention from interfering in Hungary in 1956 than Goldwater’s belief that we should have flown in a force with tactical nuclear weapons. It will be interesting to see during the campaign how Eisenhower, even with his well-practiced gift for the vacuous and the equivocal, will be able to circumvent the fact that he is supporting a man who repudiates the best part of his own administration.

It is essential to understand that Goldwater is not merely advocating the conventional “tough” line in foreign policy, for which a rational case can be made. He goes beyond it to demand what can only be called the crusader’s line. He sees it as a holy war. His goal is not merely peace, security, and the extension of our influence, but an ultimate total victory, the ideological and political extermination of the enemy. “Our objective must be the destruction of the enemy as an ideological force possessing the means of power” The ambiguous world in which we have already lived for twenty years is to Goldwater a fleeting illusion; what is ultimately real is Armageddon—total victory or total defeat. “The only alternative [to victory] is—obviously—defeat.” The idea that the cold war may have somewhat changed its character in recent years is not only unacceptable, it is intolerable. Flexibility in conducting it is treasonable; and Goldwater has skirted the ideas of the paranoid right in asserting that the Democrats have led us toward unilateral disarmament in pursuit of their “no-win” policy.

This point of view, it must be clear, is very far from the old isolationism and much closer to the American missionary impulse that once sent us out to make the world safe for democracy. Although he has taken a rather dim view of most kinds of foreign aid (restoring freedom to the world must not be too expensive), Goldwater takes the broadest view of our commitments outside our own borders. It is our business to counterpose our force to that of Communism everywhere on the globe. Goldwater’s accusation that President Johnson’s acceptance speech was an isolationist document is in keeping with this commitment, and helps to define the difference between the two. Johnson hopes for a continuing relaxation of international tensions which will free us to renew our efforts to solve some of our pressing domestic problems. Goldwater, at least until yesterday, so to speak, proposed to dismantle our federal apparatus in the hope that our domestic problems will somehow be solved by other means, and urged that we be lulled by no relaxation, that we press on with that ultimate conflict which is the true purpose of our existence on earth. In one of his most memorable sentences, he has written: “We want to stay alive, of course; but more than that we want to be free.”

I suppose it will always remain somewhat puzzling why a prosperous provincial merchant, speaking to a prosperous country with unprecedented facilities at its disposal for all the varieties of high and low enjoyment, should choose to commit himself to such a view of the world, should prefer to see the cold war not as the tragic burden of our epoch but as an opportunity and a challenge in which the meaning of our life can be found. In this respect Goldwater, the nuclear gambler, takes his place not among the conservatives of the world, but among the millennial dreamers, the visionaries, and the inspired agitators. He belongs, it appears, to a type of man, found perhaps in unusual numbers in this country, for whom the values to be found in any situation arise not out of the opportunities it offers for the peaceful arts of negotiation and persuasion but rather out of the chances it gives to the qualities of aggression and what is sometimes called virility.

Goldwater also appeals, of course, to a deep and widespread strain of impatience in the American temperament, against which thus far our sagacity and our passion for the peaceful enjoyment of our national life have prevailed. It is difficult for most Americans to come to terms with the situation of limited power in which we now live. The circumstances of our historical development have encouraged a complex which D. W. Brogan once called “the illusion of American omnipotence”—the notion that we are all-powerful in the world, and that failure to achieve our ends arises only from unforgivable weakness of will or from treason in high places. In our early national experience, all our military goals were realized with extraordinary ease and at an extraordinarily low price. Our foes—Indians, Mexicans, the decaying Spanish Empire—were easily vanquished; and while it is true that we also fought England, it was at a time when she was fighting with Napoleon for her life and her operations against us had the character of a sideshow. Under these circumstances, our expansion across the continent and our hegemony in the Western Hemisphere were achieved without great standing armies, huge military budgets, long casualty lists—in short, without those staggering costs that the peoples of Europe have always paid as the price of national security or national conquests. Even our entry into the first World War did not change this frame of expectation, for we came in when the contesting powers were bled white and our entry quickly tipped the scales.

It was only in fact after the second World War that we began to realize that we were living in a situation which we could not fully control. This realization explains, I believe, the hysterical reaction to the Korean war which brought the era of MacArthur and McCarthy. Our policy-makers have responded soberly enough, on the whole, to the realities of limited power, but these realities remain a tormenting novelty to the public at large. Men like Goldwater cater to the impatience of people who find it inconceivable that our cold-war frustrations, in Vietnam, Cuba, Laos, or Berlin, can be the consequences of forces outside our control, and who still hope that all our problems can be solved by some simple, violent gesture. Americans yearn to go back to the days of cheap and quick triumphs, and Goldwater appeals to this wishfulness when he promises that we will at one and the same time destroy the power of the Communist world and pay much lower taxes.

While Goldwater’s approach to the cold war appeals to a strong strain of aggressiveness and impatience, this appeal is more than counterbalanced by the anxieties it arouses. The public does not want to take unnecessary risks of being incinerated to further Goldwater’s crusade, and the Senator has never been able to offer them satisfactory reassurance. Asked whether the attempt to press every crisis to a victorious solution will not eventually bring a general war, he can only promise that if we main in our superiority in weapons, the Soviet will never strike. It hardly occurs to him that this is a promise on which he himself cannot deliver, and that he relies on Mosocw and Peking to fulfill it for him. However, there is a curious passage in Why Not Victory? in which he flatly admits that they will not. The Communist world, he there asserts, is likely to resort to war only under one of two conditions. The first is, of course, if we invite their attack by political weakness and military disarmament. But the other is “if there is a decisive switch in world affairs to the point where it is obvious they are going to lose.” For the moment the Senator characteristically forgets that this is precisely the point to which he is constantly urging us to press them.

V

If the polls are approximately right, as I believe they are, Goldwater starts his campaign far behind, and stands in danger of being remembered as the Republican who lost Vermont. Branded as a reckless extremist, he now has only about a month left to work a drastic change in his reputation. The technique he has always relied upon may have come to the limit of its usefulness. Goldwater has always taken advantage of the fact that the masses do not think in syllogisms but in striking images and dramatic events. In counting upon the irrationality of the public, however, he has perhaps failed to estimate the risk he has been taking of running afoul of its feeling for character. The American electorate may not try to assess its leaders by engaging in a close rational appraisal of their programs; but it does look for a certain quality and consistency in character, and seems to feel its way toward a judgment on these grounds. It does not demand that a man be wholly rational in argument, much less that he be brilliant or witty; but it asks, especially in these times, for a certain steadiness, moderation, and reliability. The process by which it arrives at a judgment is not infallible, of course, but neither is it altogether ineffective. In our own time, our more menacing public figures, such as MacArthur and McCarthy, who had very real discontents to exploit, were in the end rejected, the first because he seemed too grandiose and aggressive, the second as too sly and sinister.

Goldwater can appeal with some effect to a variety of irritations and complaints, but it is difficult for him to find a positive issue, one that does not rest in being against something or on desiring to restore something out of the unrecoverable past. In this respect he is at the same disadvantage in campaigning against Johnson and the Democrats as the moderate Republicans have been in past years. The Democrats encompass such a wide range in the American consensus that they leave little room for alternative programs. Republican issues today are made of odds and ends, and they are mainly negative. The Bobby Baker penumbra has a limited yield, and that chiefly among those already persuaded. The white backlash seems to be less portentous than a month ago, though we are certain to hear a good deal about violence and crime in the streets. The effort to disembarrass himself of the onus of nuclear recklessness will take up a great deal of Goldwater’s time, and we may here see more of his ingenious improvisations. The charge that President Johnson authorized the discretionary use of tactical nuclear weapons in the Gulf of Tonkin was another of his experiments in salesmanship, an attempt to suggest that perhaps we are really all nuclear gamblers together. It may be safer and more effective, however, simply to identify the Republican party as the party of peace and to affirm his own intention to carry on with its traditions. In Goldwater’s first campaign speech at Prescott, Arizona, the word “peace” occurred twenty times.

We seem sure, then, to hear a good deal more of Goldwater III during the coming weeks. Goldwater must rely upon the hope that his appearance on the television screen, a handsome, earnest, well-meaning man, preaching relatively familiar Republican doctrine, will effectively contradict the idea of the inhumane and trigger-happy extremist about whom the Democrats will be talking. But here he must thread his way rather nicely through a strategic dilemma: without a great deal of Goldwater III, Goldwater I can hardly be effaced; and yet if the true believers have to swallow too much of Goldwater III, their enthusiasm may wane and the cult will begin to fade. All this recent talk about compassion in government for example, must surely strike them as a lot of malarkey, and it was not for this thin brew that they put Goldwater where he is.

Although we have good reason to be sanguine about the results of the election, the outlook for the Republican party, and hence for the health of our two-party system, is much more clouded. The events at the Cow Palace showed what an unusual kind of control Goldwater had acquired over his party. He won his nomination not by demonstrating his popularity with the rank and file of its voters or by negotiating with its other leaders but by drawing around him a disciplined personal following, linked to him by strong idealogical ties and a messianic faith. His grip on the party apparatus is daily being tightened, and some of his most forthright Republican foes may be defeated this fall precisely because his name leads the ticket.

One cannot therefore lightly assume that it will be as easy to dispose of Goldwater as is usually the case with badly defeated candidates. The disaster toward which he appears to be heading may shake his cult to the point at which it will be possible to dislodge the Goldwaterites from the party controls, but only at the cost of bitter struggles in many key states. The problem confronting the moderate Republicans if and when they retake the party from him remains inordinately difficult. There is, after all, one point on which the right-wing Republicans have made a good case: the Republican moderates lack a firm, separate identity. The whole spectrum of middle-ground positions has been pre-empted by the Democrats—and never so effectively as under President Johnson. So long as the Republican moderates are committed to keeping their party in the American mainstream, they have had little to offer but a choice that is only an echo.

It is always dangerous to predict the demise of a major party in our political system, as the commentators of the 1920s discovered who persistently heralded the imminent disappearance of the Democrats. But Goldwater may have given the Republican party the coup de grâce as a genuine major-party competitor. We may be headed for a kind of party-and-a-half system (a situation comparable to Britain’s if Labour loses this year) in which the tasks of government normally rest in the hands of the single major party, and in which the alternate party can expect to return to power under, a most extraordinary combination of circumstances. Whatever may be said about the limitations of the two-party system in the past, it is hard to believe that such an arrangement would be better or safer for us, especially since in this country the minor party would always be a sitting duck for the ultras and the cranks.

One can only sympathize, then, with the Republican moderates in the formidable double enterprise that lies ahead of them, first of retaking the party from the cult that now runs it and then of finding for it a program that steers clear of right-wing ultra commitments and yet can be distinguished on sound and significant points from what the Democrats have to offer. As one contemplates the difficulties that bestrew this course, one realizes that, come what may, Barry Goldwater has already left a deep scar on our political system: this self-proclaimed “conservative” is within a hair’s breadth of ruining one of our great and long-standing institutions. When, in all our history, has anyone with ideas so bizarre, so archaic, so self-confounding, so remote from the basic American consensus, ever gone so far?

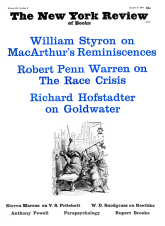

This Issue

October 8, 1964