Here are portraits of two plutocrats, two playboys of the western world, Basil Zaharoff (1850?-1936) and Nubar Gulbenkian (1896—). A first glance at their photographs, the shrewd grin between the topper and the beard, and you think of Uncle Sam. But turn a page and see them at Buckingham Palace, solemnly displaying their orders and cocked hats, and you realize that they’re truly English gentlemen, almost archetypal—Sir Basil, the wicked squire, and lovable Mr. Nubar, eccentric huntsman and munificent heir. The late Sir Basil Zaharoff (alias Z. B. Gortzacoff, Z. Z. Williamson, etc.) is fretfully condemned by his biographer: this armament salesman’s record of skilled work on international defense programs is dramatized into a “portrait in evil” of a Peddler of Death. But the memoirs of Nubar Gulbenkian, who is still alive, have been warmly received in Britain; most millionaires are mean and gloomy, runs the cant, but jolly Nubar does enjoy himself. The pair are presented as vulture and macaw.

Yet, in some respects, they’re birds of a feather. Though neither fought for the King, both courageously attempted war-time espionage on his behalf. Both combined their English distinctions with membership of the Légion d’Honneur. Both have helped organize the world’s oil oligopoly—though failing in the attempt to keep US interests out of the Middle East. Both seem to have originated in the old Ottoman Empire and might, I suppose, have remained there, had not the world’s center of power moved so obviously westward.

Nubar Gulbenkian was born at Kadi Keui on the Bosphorus. Because of racial disturbances, he was conveyed to Victorian England in a Gladstone bag. His Armenian grandfather had been an over-powerful citizen; one of his servants died under punishment and the master’s comment—“I told you to beat him, not kill him”—became a family joke. Nubar caps this horrid anecdote with an urbane Horatian tag (about “golden mediocrity”), as befits his cheerful claim to be an “English gentleman”; but he has retained an unEnglish awareness of the barbarities resulting from economic injustice and a willingness, rare in his class, to face the brute facts. As the son of Calouste Gulbenkian—whose pioneer work on oil exploitation brought him in 5 per cent interest on the declared profits of Anglo-Persian (now British Petroleum) and Royal Dutch Shell—Nubar had a different standpoint from most of his peers and contemporaries. He was more cosmopolitan—more neo-colonialist, perhaps—and had a sharper comprehension of the impact of western investment on the outside world. Touring the Mexican oilfields in the 1920s, he stopped to photograph a hanged terrorist; police offered to bring out two more to be executed for the gentleman’s benefit. Another cop accidentally shot a bystander outside a night club; the doorman drew Nubar inside: “Come in, sir. It’s only a little man they have killed.”

Nubar shudders like a gentleman, but accepts the situation. Much of this rich man’s story is taken up with expensive trivia, orchids, horses, food he’s consumed, operas and royal beanos he’s yawned through, legal quibbles about his family’s cultural foundation; but he also reflects honestly on the sources of his fortune:

There is a case for the limit to the remuneration of capital…From 1914 to 1953, the Gulbenkian family never had more at stake in the Middle East than between half a million and one million pounds. Since 1955 alone, the Gulbenkian interests have been deriving something between five and six million pounds a year on that investment, and it follows that the oil groups are making the same relative profit…

Apparently he can see little moral objection to his being expropriated by popular governments. Then, he wants to know on what basis oil companies declare their profits. Surely “they can’t be trying to suggest that buying and selling oil is more profitable than producing it”? This is a problem that has puzzled many. (See Oil Companies and Governments by J. E. Hartshorn, passim.)

A second-generation plutocrat can afford such niceties. It’s not likely that Nubar’s pioneer father had time for them. Nor did Calouste’s contemporary, Basil Zaharoff. The memory of this distinguished defense expert ought, by rights, to be honored in Britain, at a time when the government is engaging an “arms super-salesman” to compete with US munitions exporters. Not so; the Knight of the Bath is as unpopular as ever. Is it simply because Zaharoff was born God knows when (1849-51?) and God knows where—Mouchliou, Odessa, Tatavla? Bernard Shaw was very probably thinking of Zaharoff when, in Major Barbara, he defended the foundling arms magnate, Undershaft, against the humbugs. Undershaft declaims the creed of the Armourer:

To give arms to all men who offer an honest price for them, without respect of persons or principles…All have the right to fight; none have the right to judge.

Just so, Zaharoff claimed to be “a simple ironmaster”; but he has been severely judged, detested more than others who make their career out of warfare. Shaw hinted at the race-feeling behind his unpopularity, when he created Lazarus, the sleeping partner, a gentle musical Jew who got the blame for Undershaft’s ruthless commercialism.

Advertisement

Though the native gentry of England welcome the talents of men like Zaharoff and the Gulbenkians, they can turn nasty, especially in war-time. Young Nubar was told in 1914 that his oriental origin debarred him from H.M. forces. In World War II, he records resentfully, “a high authority in England” sneered at his family’s arrangements: “Papa is sitting in Vichy, in case the Germans win, and little Nubar is sitting in England in case the Allies win—so whatever happens they will be on the right side.” Nubar dismisses this charge with a patriotic Harrow-and-Oxford snort. There is perhaps a touch of Schadenfreude when he notes the British establishment’s treatment of the Gulbenkian’s Jewish rivals, Lord Bearsted and Robert Waley Cohen. “What,” asked the latter, “would the Admiralty do if the Royal Dutch Shell refused to sell any oil?” An admiral, “Blinkers” Hall, retorted: “Well, there will always be a lamp-post in the street on which to hang Robert Waley-Cohen.”

Nubar Gulbenkian is wary of the mob. In 1939 he “had a Wellsian vision of the terror-stricken populace fleeing the towns and cities…They might seize by force any big house…” To avoid this danger, he “took a very small workman’s cottage—just the sort of place which would escape the notice of marauding, frightened refugees.” Overcautious, this. British plutocrats, even if foreign-born, have been pretty safe from mob-fury in this century (though, admittedly, members of the native oligarchy are capable of disseminating a little racialism downwards, when it suits their convenience). Nubar’s upper-class schooling and horsemanship helped him win the kind of popularity accorded to a duke or an Aga Khan. Touchingly, he records a tribute to himself (“old Gorblimey”) overheard in a lavatory at a point-to-point (horse-race). “Gorblimey? ‘E can’t ride for little green apples,” said one “yokel”; but another replied, in the same quaint dialect, “Yus, but the bugger’s got guts.”

A Conservative minister suggested another name—two, in fact—for “old Gorblimey,” when advising him to enter politics: “You’ll find people will want to know what your name was before it was Gumbley. If you don’t start off by calling yourself Gulleybanks, then you’ll have to say your name used to be Gulbenkian. And then they’ll know you’re really a foreigner.” This remark reflects the reservations of his class, a race-snobbery which is disquietingly common. J.M. Cohen’s Penguin Book of Comic Verse records some striking period examples—jeers at “Mr. Semitopolis” and verse like this:

They say the Duke of Deal is wont to deck

His forehead with a huge phylactery.

They say Sir Buckley Boldwood is a Czech

And Lord Fitzwaldemar a Portugee.

They say Lord Penge began in poverty

Outside Pompeii, selling souvenirs…

In 1965, Donald McCormick takes much the same tone with Zaharoff—originally “a brothel tout in Constantinople,” he believes. But was Sir Basil a Russian or a Greek, a heathen Turk or Jew? The author toys uncertainly with the scabrous possibilities, quoting newspaper abuse against “the Levantine,” some of it from Lord Beaverbrook. (McCormick himself works for another Canadian press baron, Lord Thomson.) He seems to suggest that Sir Basil was in some way racially inferior to these enobled immigrants; but perhaps I misjudge him.

His biography is so thick with rumors and legends that it’s hard to be sure of anything; but the anecdotes—and McCormick’s severity—do at least help to explain Sir Basil’s unpopularity. The indictment is, basically, that Zaharoff lacked loyalty to “national interests” or even to business partners; perhaps he was merely less hypocritical than others. Apparently, his first big coup was selling Nordenfeldt’s submarine to both Turkey and Greece. Then, after discrediting and sabotaging the Maxim gun, he arranged the Maxim-Nordenfeldt-Vickers merger; during the Boer War this firm made large profits by supplying arms to both sides. By 1905 Zaharoff was drawing £86,000 a year from Vickers; four years later the British Government was treating the firm almost as a state enterprise and, in World War I, employees of the arms firm were introduced into the Civil Service. We may disapprove of this kind of state-military-industrial complex—but it’s hard that Zaharoff should get all the blame. As for industrial espionage and competitive public relations, there’s nothing discreditable about these things nowadays, surely.

McCormick holds that the conduct of the 1914-18 war was influenced by the Lloyd George-Zaharoff desire to extend it eastwards, in order to gain control of oilfields. Zaharoff’s visit to the US was intended to secure American military aid—while discouraging direct intervention for fear of American involvement in the Middle East. After the war, he established in France the Société Générale des Huiles de Pétrole, of which Anglo-Persian held 45 per cent of the share capital. Much of the French capital Zaharoff supplied himself. A principal aim, claims McCormick, was to ensure that Western Europe gained oil concessions which would make them economically impregnable. He held a rather similar attitude to the armaments industry, wishing to see the European firms in an interlocking cartel of interests which would co-operate and fix prices; one of his arguments is very familiar—that scientific discoveries in armaments lead to technological improvements in civil industry.

Advertisement

Thus, when we read that Zaharoff was considered “a sinister influence” in the US during the disarmament campaign of the 1920s, there’s an obvious suspicion that his anti-American, pro-European oil policy was partially responsible. At a political convention, his straightforward anti-communist posture—accepting Franco Spain but drawing the line at Nazi Germany—would not seem too outrageous at a modern NATO conference; nor would his insistence on balanced forces in rival nations, each maintaining an arms-based economy. His international (or “unpatriotic”) outlook was one of his strengths. He supported the British war effort on his own terms, ensuring that all his factories and all sources of armament-producing raw material should remain intact. No offensive action was taken by the Allies against Briey or Thionville, although they were of vital importance to the Germans for mineral supplies. “The censor is our best ally,” joked Zaharoff. After the war, he helped secure lenient treatment for his German rival, Herr Krupp, pointing out on his Agence Radio that Krupp’s products had made a considerable “contribution to the deaths of German soldiers.”

One trouble with these two success stories is that they keep challenging the reader to pass moral judgments, when we may not wish to do so. McCormick is so severe on Zaharoff that one may feel over-inclined to defend him. Nubar Gulbenkian priggishly asks our advice and approbation:

I was faced with a moral problem. On the one hand, I could not allow people who had trusted the Gulbenkians to sell out their share at £4 10s., when I knew quite well that in a few days they would be offered £6. On the other hand, I did not want to let fall the slightest hint of what was going on.

He resolved the problem to his own satisfaction; but those of us who are unable to consider “business ethics” as a subject for serious study will feel inclined to laugh. It is not in the puny capitalist conscience that the glamor of wealth resides, but in romantic autocracy and extravagant gesture. Here Zaharoff wins hands down. Young Nubar had a safe mistress selected for him by his father; but Zaharoff won a Spanish duchess, after duelling with her husband. At table he roared: “There is only one real kind of beauty and that is a woman with white gold hair. Only women with your hair should be allowed to remain in this restaurant.” The other women were obediently cleared away. Zaharoff was one of nature’s gentlemen. Nubar is second-generation stuff, lacking the style and distinction of the monstrous parvenu.

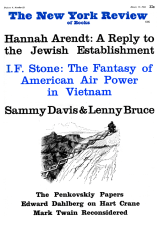

This Issue

January 20, 1966