It would be a pleasure to be able to praise unreservedly this latest work of Professor Bruner. He is a humane, perceptive, and intelligent man, who likes children and is deeply concerned with their thinking and learning. In the controversies that divide education, his head and his heart are very often in the right place. He has arrived at some important understandings about teaching, which he here sets forth. How easy it would be to join the chorus of worshipful critics who are or soon will be calling this book great, challenging, revolutionary, destined to change the course of American education, and so on. But it is not a very good book, certainly not a tenth as good a book as a man with Bruner’s insights, talents, and opportunities ought to have written. This is not to say that he ought to have written an entirely different book; only that he ought to have written this one better.

What is wrong with it? First, the title. Why so ponderous? Why not Toward Better Teaching, or How We Can Teach Better, or Can We Teach Better? The difference is important. Few elementary school teachers read many books, as it is. Had the book a simpler title, at least some teachers might have been tempted to take a look at it. As it is, not a teacher in a hundred, unless made to, will so much as open it. If they do, they will probably feel, after the first two or three pages, that the book is not for them. As academic writing goes, this book is not badly written; but why should Bruner write like an academic when he knows how to write clear, strong English? On page 25 we have “heavy dentition.” Why not “teeth”? On page 36 we have, “These are the furbelows of documentary short supply.” Why not, “We keep such junk only because we don’t have much junk to keep.” And so on. Bruner has often said (though this contradicts much of Piaget) that any subject can be made meaningful to children of any age, and if children, certainly adults. Surely, then, a writer, whatever his subject, ought to try to make his ideas clear to as many people as he can. What use is a book about teaching that most teachers will not understand? Bruner might reply that his book is not aimed at classroom teachers, but at the administrators, supervisors, publishers, and instructors, who will one day tell them what to do. If so, his aim is bad, for no important changes in education can be made that classroom teachers do not understand and support.

The book is very loosely and weakly organized, if it can be said to be organized at all. It is a collection of speeches, made into essays. Bruner says they have been much revised and edited. They do not show it. They sound off the cuff—witty and learned, no doubt, but off the cuff just the same. They are not tied together by any connective material, or clear plan of organization, so that those unfamiliar with Bruner’s work will find it hard to know what his thoughts are, or why he thinks them, or which of them he feels least or most certain, which least or most important.

Still, they do express a point of view about knowing and learning. It is one which I feel, useful and true though it may be in some details, to be fundamentally in error. Put very simply and briefly, it is this. The learning and knowing of a child goes through three stages. In the first, he knows only what he senses, the reality immediately before him is the only reality. In the second, he has collected many of his sense impressions of the world into a kind of memory bank, what Bruner, and I, call a mental model of the world—though we mean quite different things by it. Because he has this model, the child is aware of the existence of many things beyond those immediately before his senses. In the third and most advanced stage of learning, the child has been able to express his understandings of the world in words and other symbols, and has also learned, or been taught, by shifting these symbols in accordance with certain logical and agreed on rules, to predict, in many circumstances, what the real world will do.

A SIMPLE EXAMPLE—Bruner’s own—will make this more clear. “Or take the five-year-old, faced with two equal beakers, each filled to the same level with water. He will say that they are equal. Now pour the contents of one of the beakers into another that is taller and thinner and ask whether there is the same amount in both. The child will deny it, pointing out that one of them has more “because the water is higher.” The child is fooled by what he sees, and because he has nothing to go on but what he sees. But when they get older, children are no longer fooled; they say the amounts remain the same, and explain what they see with remarks like, “It looks different, but it really isn’t,” or “It looks higher, but that’s because it’s thinner,” and so on. Bruner believes that it is because the older children can say such things, because they have learned, so to speak, to solve this problem by a verbal formula, that they are not fooled by what they see. As he puts it, “Language provides the means of getting free of immediate appearance as the sole basis of judgement.”

Advertisement

Yes, it does. But it also provided Aristotle with the means of saying, as men said for many centuries after him, along with many other logically arrived at absurdities, that heavy bodies fall faster than light ones. When we try to predict reality by manipulating verbal symbols of reality, we may get truth; but we are just as likely, even more likely, to get nonsense.

In this matter, Bruner’s theories are closely related to those of Piaget. To see the flaw in their reasoning, we must look at one of Piaget’s simpler experiments. Before a young child he put two rods of equal length, their ends lined up, and then asked the child which was longer, or whether they were of the same length. The child would say that they were the same. Then Piaget moved a rod, so that their ends were no longer in line, and asked the question again. This time the child would always say that one or the other of the rods was longer. From this Piaget concluded that the child thought that one rod had become longer, and thence, that children below a certain age were incapable of understanding the idea of conservation of length. But what Piaget failed to understand or imagine was that the child’s understanding of the question, and his own, might not be the same. What does a little child understand the word “longer” to mean? It means the one that sticks out. Only after considerable experience does he realize that “Which is longer?” really means, “If you line them up at one end, which one sticks out at the other?” The meaning of the question, “Which is longer?”, like the meaning of many questions, lies in the procedure you must follow to answer it; if you don’t know the procedure, you don’t know the meaning of the question.

Many, perhaps all, of Piaget’s and Bruner’s experiments on conservation, and other concepts as well, are flawed in the same way. A child is shown a lump of clay; then the experimenter breaks the lump into many small lumps, or stretches it into a long cylinder, or otherwise deforms it, and then asks the child whether there is more than before, or less, or the same. (When a movie of this experiment was shown at one of Bruner’s colloquia at Harvard, nobody thought it worth mentioning that most of the time the child was looking not at the clay but at the face of his questioner, as if to read there the wanted answer—but this is another story.) The child almost always answered “More.” Piaget, and later Bruner, say, “Aha! He says it’s more because it looks like more.” But to the young child the question, “Is it more?” means “Does it look like more?” What else could it mean? He has not had the kind of experience that would tell him that “more” could refer to anything but immediate appearance.

I HAVE OFTEN THOUGHT if little children really believed about conservation what Piaget says they believe, how would their knowledge lead them to act? To make any good thing—a collection of toys, a piece of candy or cake, a glass of juice—look like more, they would divide it, spread it about. But they don’t break the candy in little bits and pour their juice into many glasses; if anything, they tend to do the opposite, gather things together into a big lump. I also asked myself, what kinds of experience might make a child aware of conservation in liquids? How would you learn that, given some liquid to drink, whatever you put it in, you got only the same amount to drink? Well, you might learn if liquid was scarce, and every swallow counted, and was counted, and relished. So I was not surprised to hear that, when someone, perhaps Bruner himself, tried the liquid conservation problem in one of the desert countries of Africa, the children caught on at a much earlier age. As they say, it figured. Finally, there are some very important respects in which all children do grasp the principle of conservation, and this long before they talk well enough to learn it through words. Bruner says little children are fooled by their senses because they have no words to make an invariant world with. But the world they see, like the world we see, is one in which every object changes its size, shape, and position relative to other objects, every time we move. It is a world of rubber. But even by the time they are four, or three, or younger still, children know that this rubber world they see is not what the real world is like. They know that their mother doesn’t shrink as she moves away from them. And this is a far more subtle understanding than the ones that Piaget and others like to test.

Advertisement

From this fundamental error—the idea that our understanding of reality is fundamentally verbal or symbolic, and that thinking, certainly in its highest form, is the manipulation of those symbols—flow many other errors. Bruner’s six “benchmarks of intellectual growth” express a number of them. One is “Independence of response from the immediate nature of the stimulus.” He speaks of “the child’s being able to maintain an invariant response in the face of changing states of the stimulating environment…” This sounds to me like Dean Rusk in Vietnam. I would counter it with Dr. Caleb Gattegno’s remark that what the world needs is a few more people who can take a hint from experience. Another benchmark: “Intellectual development depends upon a systematic and contingent interaction between a tutor and a learner…” Sometimes, yes. Most of the time, the problem is to get the teacher out from between the learner and the material, and many of the best teachers I know are trying to bring about (to quote Gattegno again) “the subordination of teaching to learning.” Still another benchmark: “Teaching is vastly facilitated by the medium of language…” Perhaps, ideally it could be; in practice, as Bruner would know if he did a stretch of duty as a classroom teacher, the reverse is more often true. Our explanations confuse more than they explain, and classrooms are full of children who have become so distrustful of words, and their own ability to get meaning from words, that they will not do anything until they are shown something they can imitate.

WHAT WE MUST REMEMBER about words is that they are like freight cars; they may carry a cargo of meaning, of associated, non-verbal reality, or they may not. The words that enter our minds with a cargo of meaning make more complete and accurate our non-verbal model of the universe. Other words just rattle around in our heads. We may be able to spit them out, or shuffle them around according to the rules, but they have not changed what we really know and understand about things. One of the things that is so wrong with school is that most of the words children hear there carry no non-verbal meaning whatever, and so add nothing to their real understanding. Instead they only confuse them, or worse yet, encourage them to feel that if they can talk glibly about something it means that they understand it. It is a dangerous delusion. As Robert Frost said, in the poem “At Woodward’s Gardens,” “It’s knowing what to do with things that counts.” No dozen university professors, however many theories they might spout, could ever know as much about the ballistics of a batted baseball as Willie Mays. They might have the words, but he has a model that works—and that is what real knowledge is about.

Bruner appears to be in a big argument with conventional teachers, but their differences are not so fundamental or important as he thinks. They both think their job is to plant strings of words in children’s heads. What he says, and argues about, is that some word strings are more important than others. He sees a kind of hierarchy of ideas, with a few master ideas at the top, like the master keys that will open all the doors in a building. If you know these master ideas, then it will be easy to find out or understand anything else you want to learn. The notion is plausible and tempting. What Bruner, like most conscientious teachers, does not see is that each of us has to forge his own master key out of his own materials, has to make sense of the world in his own way, and that no two people will ever do it in the same way. If Bruner has his way, every sixth grader in the country will one day be able to say that what makes men human is that they have opposable thumbs, tools, language in which word-order influences meaning, etc. For Bruner, these verbal freight cars carry an enormous load of associated meaning. For the students, they will be just a few additions to their lists of “cepts”—pat phrases you put down on an exam to make a teacher think you know the course, empty of any other meaning.

WHATEVER MAY BE the weakness in his theories, Bruner has many insights into what makes good teaching, and sets forth a number of them in this book. Too often, though, he does so in such a way that most readers will fail to see why and how they are important. Indeed, in places Bruner seems to have failed to see this himself. On page 4 he speaks of the distinction “between behavior that copes with the requirements of a problem and behavior that is designed to defend against entry into the problem. It is the distinction one might make between playing tennis on the one hand and fighting like fury to stay off the tennis court altogether on the other.” This is an extraordinarily important insight, but even Bruner’s example shows how little he has pursued or understood it. There are many more ways of resisting tennis than simply refusing to play it. I remember, when about fifteen, watching my sister play, or pretend to play. After every swing she would grimace, or giggle, or make some grossly clumsy and comic gesture. At the time I thought this was for the benefit of watching boy friends, actual or potential. Only years later did I see that they were her way of defending against the problem of learning to play tennis, and at that, only one of a whole range of such defensive behavior, in which someone appears to be committing himself to a problem or activity, while in fact limiting his commitment, or holding back from it altogether. Much of what adults do in many circumstances and almost all of what children do in school is behavior of this kind. But Bruner has not seen this; indeed, he has turned his back on his own insight, saying, “We would have floundered in studies of how children learn to avoid learning, which was not our intent…” Floundered, indeed! when this is what most school behavior is about. When I think of some of the research that Bruner and his colleagues have been doing in recent years, such as the eye camera project, I hardly know whether to laugh or cry.

On page 4 is another important insight not followed up, and therefore not fully understood—the remark of the mathematician David Page that “when children give wrong answers it is not so often that they are wrong as that they are answering another question…” This is only the beginning of the truth. Sometimes children give wrong answers because they have not understood a particular question. Most of the time, the trouble lies deeper. It isn’t just that they do not understand the particular question, but that they don’t understand the nature and purpose of questions in general. It isn’t just that they now and then give an answer to a wrong problem, but that the answers they give are rarely related to any problem. A question is supposed to direct our attention to a problem; to many or most children, it does the opposite—directs their attention away from the problem, and toward the complicated strategies for finding, or stealing, an answer. But we must look further yet; for a great many of the answers children give in school they do not expect or in some cases even intend to be right. They are desperately wild guesses, or deliberately wrong ones, thrown out in the hopes of evading the issue, or even of failing on purpose, to avoid the pain and humiliation of fruitless and futile effort.

If the new educational reformers—Bruner aptly labels them “Widener-to-Wichita” people—do not see more clearly than they do, it is not because they have not good eyes, but for two other reasons. The first is that they tend to start talking before they have done enough looking, and their theories obstruct and blur their vision, and the vision of others, as Piaget has blurred Bruner’s vision. The second is that their contact with schools is so special and artificial that they don’t really know what school is like. On the whole, only the most successful and confident schools will even let these high-powered visitors in. Then they steer them toward their “best” classes, where a well-prepared teacher and students put on a good show. Even when the visitors do the teaching, this too is artificial. They hold no power over the students, have no rewards and penalties to hand out. The children are as glad to see a visitor come to class as to see a guest come home for dinner. For a while, they are safe. The visitor will cause them no trouble, and while he is there, they are much less likely to get trouble from the usual sources. So when the reformers, who, like Bruner, are good with children, invite them to play intellectual games, the children play freely, and therefore well. Later, the reformers go away saying, “See? Anyone can do it!” not realizing that their success came, not so much from their ideas, but from their having, by being there, turned the classroom into a very different kind of place.

AT TIMES, BRUNER seems to understand this. Thus, on page 52, he says, “The ability of problem solvers to use information correctively is known to vary as a function of their internal state. One state in which information is least useful is that of strong drive and anxiety.” On page 127 he summarizes the argument of the excellent chapter, “The Will to Learn,” in this way: “The will to learn becomes a ‘problem’ only under specialized circumstances like those of a school, where a curriculum is set, students confined, and a path fixed. The problem exists not so much in learning itself, but in the fact that what the school imposes often fails to enlist the natural energies that sustain spontaneous learning—curiosity, a desire for competence, aspiration to emulate a model…” This is excellent. Then, on page 128, “External reinforcement may indeed get a particular act going and may eventually lead to its repetition, but it does not nourish, reliably, the long course of learning by which man slowly builds in his own way a serviceable model of what the world is and what it can be.” No, indeed it does not; but this is what the progressive, or libertarian educators—call them what you will—have been saying for years, and decades. Bruner’s own The Process of Education, as Paul Goodman pointed out in Compulsory Mis-Education, made the same points. One might suppose that Bruner and his colleagues would show some interest in the schools that try to practice what he preaches—Summerhill, Summerlane, Green Valley, and others—all the more since in such schools many children do as much as five years of schoolwork in one. But of such interest there has been no sign.

Other valuable insights deserve mention. On page 68 he says that children should do things before being made to talk or write about them, and on page 71: “A curriculum, in short, must contain many tracks leading to the same general goal.” Yes, indeed! On page 109: “…words do not fully exhaust the knowledge and sensibility contained in our acts and our images.” Very true; but much of the time, Bruner, like Piaget, talks as if the measure of what we know about something is what we can say about it. On page 115: “…an important early function is served by the child’s omnivorous capacity for new impressions. He is sorting the world, storing those things that have some recurrent regularity and require ‘knowing’…” But Bruner seems not to understand the power and efficiency of this kind of early learning, nor the waste and loss that come when we do not allow it to continue. On page 118: “We get interested in what we get good at.” Then why not have, in school, a much greater variety and range of activities—arts, crafts, sciences, athletics—that children might get good at? Why give all the rewards to only one or two kinds of competence? On page 136: “…too strong an incentive for learning narrows the learning…” On page 158: “Young children in school expend extraordinary time and effort figuring out what it is that the teacher wants…” Young children? It goes on all the way through graduate school. And why not, with the school set-up what it is? Let us hope that before long Professor Bruner writes a book exploring the consequences of these insights, and that he writes it in English that teachers will read and understand. Then he will be, as he should be, a force for real change in American education.

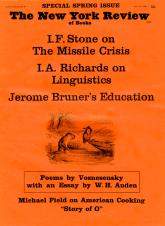

This Issue

April 14, 1966