If the sources which have contributed to the world’s highly developed cuisines are often difficult to disentangle, one can scarcely hope to find one’s way with ease through the labyrinth of American cooking. The vastness of the United States, the prodigal output of its dairies, farms, lakes, rivers, and oceans, would be enough to discourage investigation by any but the most intrepid of culinary scholars. And when one thinks of the still barely assimilated influences of the American Indians, the Africans, French, Dutch, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, and a host of lesser nationalities, the task becomes a formidable one indeed.

Yet, quite undaunted, cookbook writers by the hundreds, with little culinary and even less literary skill have, since the early 1800s, written and have had published scores of books on American cooking. Humorous, folksy, arch, or nostalgic in turn, few of the books have had anything really American to offer but the bare bones of standard recipes already picked clean by multitudes of writers before them. Unfortunately, the best of the books, among them Miss Parloa’s New Cookbook and Marketing Guide, Mrs. D. A. Lincoln’s Boston Cookbook, and Mrs. Rorer’s New Cookbook have long been out of print. But the two which have endured, Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking School Cookbook and The Settlement Cookbook, whatever their virtues may have been in their day, are in their most recent editions a tasteless pot-pourri of quasi-international recipes dotted here and there with bits of culinary Americana. They barely indicate what really good American cooking can be.

A BOOK WHICH MAKES a determined and decidedly successful attempt to do just that is The American Heritage Cookbook. Its title is misleading; only the second half of the book is a cookbook, Its subtitle describes it more precisely: An Illustrated History of American Eating and Drinking. Compiled by the editors of American Heritage magazine, this scholarly yet lively book is concerned, not surprisingly, with the development of American cooking more from the sociological viewpoint than from a culinary one. And the editors have assembled for the first half of their book a group of ten writers, only two of whom have written on culinary matters before. The others, a poet, several sociologists and social historians, bring to their task considerable insight and literary skill, and an honest appreciation of good eating and drinking untainted by even a hint of commercialism.

Particularly notable is a short piece by Marshall Fishwick on Thomas Jefferson. Mr. Fishwick explores in his essay a side of this extraordinary man too often ignored by his biographers: his love of fine French food and wine, and the astonishing amount of time, money, and energy he spent cultivating it. In 1785 Jefferson went to France to serve as American minister, and, as Mr. Fishwick describes it, “to wed Virginian and French cooking in one of the happiest unions recorded in the history of cooking.” That the marriage was indeed successful is evident when we read of Jefferson’s brilliant dinner parties in Monticello and the White House, the scope of his menus and wines, and, even more importantly, his productive investigations into French agricultural and viticultural methods. Nor was Jefferson, even as President, beneath writing out recipes for his friends and their cooks. One for meringues is especially memorable and quite precise: “12 blanc d’oeuf, les fouettes bien fermes, 12 cueilleres de sucre en poudre, put them by little and little into the whites of eggs, fouetter le tout ensemble, dresser les sur un papier avec un cueiller de bouche, metter les dans un four bien doux, that is to say an over after the bread is drawn out. You may leave there as long as you please.”

Almost touchingly, these simple meringues humanize and return to our time a man almost completely abstracted by his legends. One can hardly imagine President Johnson being concerned with such matters. Or ever being attacked, as was Jefferson by Patrick Henry, as having “abjured his native victuals.”

Of native victuals like corn, sourdough, hardtack, hominy, and the rest, The American Heritage Cookbook tells us in great detail. But more than the verbal descriptions of the food, it is the collection of colored prints, commercial posters, American primitives, and old photographs which makes this book so endearing and uniquely American. And when one finally reaches the cookbook section, the recipes in context assume far more meaning than they would have had, had they been presented alone.

As the food editor, Helen McCully, indicates, these were painstakingly collected from old cookbooks, handwritten manuscripts, historic menus (many of which are reproduced in their entirety), and other original sources. One can only admire the skill with which Miss McCully has adapted them to present-day techniques and the remarkable amount of their local flavor she has managed to retain. Most impressive is an involved recipe for a Creole Crayfish Bisque. Not often in any cuisine does one come upon a dish of such originality. Composed of a thickened soup with a base of crayfish vegetables, and tomatoes, it is seasoned vividly in the Creole fashion with lemon juice, cayenne, and tabasco. As if this weren’t enough, the bisque is served with the crayfish heads stuffed with the meat from their tails, and then baked.

Advertisement

At the other end of the scale, Miss McCully describes American country dishes like hoe cake made with cornmeal, red eye gravy made with coffee, hominy pudding, Hopping John, apple butter, and a host of other simple dishes without ever tampering with their essential innocence and charm. Her short disquisition on country hams, particularly those of Smithfield, Virginia, should make every American who reads it forswear forever those chemically pumped pieces of smoked pork which masquerade under the name of ham throughout the country today.

MARY MARGARET McBRIDE’S Harvest of American Cooking explores our culinary heritage on another level altogether. This is a book which has sold a vast number of copies since it was first published ten years ago, and during the process has accumulated a patina of respectibility it scarcely deserves. Similar in construction to The American Heritage Cookbook, it is divided into two sections, half text and half recipes. There, needless to say, the comparison ends. The first half of Miss McBride’s book is merely a repository of researched material, mostly anecdotal in character and oriented, not so subtly, towards what surely must have been the author’s commercial sponsors on her radio and television shows. That Miss McBride had a large staff to assist her is obvious from the heartfelt acknowledgments to them on the very first page of her book. We who must read her book have less cause for gratitude.

The writing is slick and lifeless, and the information, though occasionally lively, is interlarded with such passages as “I love the majesty of the view from my redwood paneled living room. I can start a chicken frying on the stove—pink and push-button modern—then look out the great windows at 40 miles of lake, with mountains piled up all around. I can pop corn in the vast blue fireplace after supper, with only the crackle of the fire and the pop of the corn to disturb the country quiet.” Reading the thousand recipes that follow isn’t much help. The first in the chapter on appetizers is called ominously, “Nutty Hors d’oeuvres.” This turns out to be a dreadful melange of pecans, almonds, filberts, olive oil, and garlic extract. From then on the spiral is downward, if that is possible: Baked Roll-Ups, Hot Tuna Sticks, Syrian Salami Kabobs, Stuffed Egg Special, and the like, ending with a section called Dips and Dunks.

Miss McBride and her staff make the customary concessions to American cooking—after all, this is supposed to be an American cookbook—by including telescoped recipes for a number of old American standbys like Johnnycake, New England Clam Chowder, and Shoo Fly Pie. But the majority of Miss McBride’s other recipes can be considered American only because she has given then American names. One is a Hot Chicken Salad Delaware consisting of chicken, celery, onions, almonds, lemon rind, cheddar cheese, mayonnaise, and potato chips, to be cooked in a casserole until brown. Another is a hamburger mixed with almost its own weight of chili sauce, catsup, mustard, horseradish and onion. And so it goes, page after page, with a Shirred Eggs Popeye here and a Lone Star Favorite there. Miss McBride’s book has been called a “classic” by people who should know better. One can only wonder if they have ever cooked from this book or even have ever read it.

TEN YEARS AGO. Helen Evans Brown wrote the West Coast Cook Book. That it is not well into its sixth printing indicates that not all American palates have been hopelessly brutalized. The late Mrs. Evans was a superb cook, and if her literary style was something less than distinguished, her taste and originality with food more than made up for it.

For some reason, the cooking of the West Coast—that is, California, Oregon, and Washington—has been largely ignored or brushed over lightly by most regional cookbooks. Even so fine a book as Sheila Hibben’s American Regional Cookery, now out of print (the best cookbooks are always out of print), gives these states short shrift: one recipe each for Washington and Oregon and only sixteen for California. And this in a book with hundreds of regional recipes! Fortunately, an impassioned partisan of West Coast cooking is James Beard. In his culinary auto-biography. Delights and Prejudices (in print, thank heaven). Mr. Beard’s lyrical paeans to Olympia oysters, Dungeness crabs, and Columbia River salmon more than make up for Miss Hibben’s omissions and place West Coast cooking in the important category where it rightfully belongs.

Advertisement

The West Coast Cook Book carries this a step further and we now have, faithfully reproduced in one volume, most of the fine and enduring dishes of the area. Among them is Cioppino. Whatever its earlier relationship to the Italian Zuppa di Pesce or to Bouillabaisse, Cioppino, in Mrs. Brown’s version, is a good, vigorous fish stew, more akin to the Italian soup than to the French one. But because it uses native shrimp, clams, and crabs, and dispenses with such refinements as the French mirepoix of vegetable and Spanish saffron, it has achieved an American personality of its own. And the same can be said for West Coast salads. Of them all—and Mrs. Brown describes many—Caesar Salad is the best known. Although its relationship to the Salade Niçoise is unmistakeable, this rough salad, like Cioppino, has become firmly entrenched in our cuisine and is evidently here to stay.

Mrs. Brown doesn’t say so, but perhaps one of the reasons that West Coast cooking is more sophisticated and more highly developed than most American regional cooking is that its roots are so firmly planted in the best wine-producing areas of the country. The development of wine has always paralleled that of good cooking in most European countries and there is every reason to hope that a similar process is taking place here. Be that as it may, the coda to Mrs. Brown’s book consists of a short history of California’s viticulture, followed by a chart listing not only the best known local varieties but also describing their color, characteristics, what to serve them with, and most informatively, the European wine each most resembles. One would have hoped Mrs. Brown’s recipes had been as impersonally and directly described as her wine chart, but still, her book is a good and honest one. And that means, of course, that the recipes work.

THE SAME CAN BE SAID OF The Chamberlain Sampler of American Cooking, with the advantage to the reader that its writing is straightforward, unmannered, and precise. The Chamberlains allow their dishes to speak for themselves. In her Introduction, however, Narcisse Chamberlain permits herself a more personal view as she surveys the rocky landscape of American cooking. She observes that it is a rare French cook who would be persuaded to adopt a Korean recipe for chicken as Californians do; French cooks singlemindedly cook dishes that are French. Diversity, Miss Chamberlain maintains, is the key to American cooking. Although we lack the strong national tradition which made the French cuisine great, or even the consistent styles which identify the Italian and Scandinavian cuisines, it is the variety of our dishes, she goes on to say, that gives them whatever importance they have.

Miss Chamberlain may be right, but because she belabors the point, one senses her wish that American cooking were a little tidier, more central, less sprawling. Surely an attempt to contain it must have determined the brevity of her book. In any event, The Sampler of American Cooking is a selection of recipes gathered from every part of the country and chosen not for any reason of order or plan, but on the basis of what the authors like. And it must be candidly said that this is as good a way to write an American cook-book as any.

The recipes illustrate convincingly Miss Chamberlain’s thesis of diversity. One reaches into the book as into a culinary grabbag and comes up with Lobster Thermidor, U. S. Senate Bean Soup, Beef Stroganoff, Tamale Pie, Cheese Blintzes, and Hominy Souffle. Indian Pudding duly makes its appearance and so does Boston Baked Beans. Recipe after recipe testifies to the profusion of our culinary influences. Thus, an American recipe for Russian Borscht, which must have had its beginnings on the West Coast (Mrs. Brown, in fact, has a similar recipe for it in her West Coast Cook Book), is more or less a traditional borscht until the cook is directed to add gelatine to it and then chill and serve it jellied with sour cream and dill. Whether this device makes the borscht American is, of course, questionable, but it is a good dish, nonetheless.

As is usual with the Chamberlain books, the recipes are accompanied by Samuel Chamberlain’s expressive photographs. The recipes are thus amplified, as it were, in another dimension. And when the photographs are particularly fine, they place a dish in its ambience as a running commentary could never do. Although one might question pairing a panoramic view of Miami with a recipe for Chicken Soup and Matzo Balls (a good one too), the rightness of most of the other alliances can hardly be disputed: a Louisianan Bayou and a recipe for Catfish Court Bouillon, a San Francisco street scene and Chinese Stuffed Lobster with Pork, the Dakota Badlands and a Scandinavian Vegetable Salad, or a Split Rail Fence in Kentucky and a recipe for Pecan Bourbon Candies.

Diversity is, indeed, the keynote in The Sampler of American Cooking and it is to the Chamberlains’ credit that they have managed to retain in each recipe, whatever its genesis, the elements which give it an American tone.

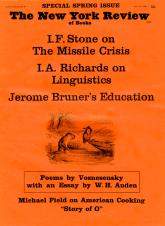

This Issue

April 14, 1966