Nietzsche called George Sand a “writing-cow.” Judging by Against Interpretation, it seems that the remarkable Susan Sontag deserves no less a tribute. Certainly in her trend-swept chronicle of cultural disturbances, here and in Europe, the ink in Miss Sontag’s pen never runs dry. On page after page, ideas, counter ideas, and perhaps even what might be termed non-ideas, squirt, trickle, or smudge. “Camp sees everything in quotation marks,” observes Miss Sontag. “It’s not a lamp but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but ‘a woman.’ ” It’s not Howard Taubman, it’s “Stanley Kauffmann.” And so forth.

Reprinted from, among other haunts, Partisan Review and The New York Review, Miss Sontag’s collected essays are brilliant, punchy, brisk, and, in a characteristically contemporary way, a little perverse. In her splendid study of the anthropologist Lévi-Strauss, Miss Sontag touches upon something of what I mean. “Modern thought,” she says, “is pledged to a kind of applied Hegelianism: seeking its Self in its Other…The ‘other’ is experienced as a harsh purification of ‘self.’ But at the same time the ‘self’ is busily colonizing all strange domains of experience.” In Against Interpretation, then, the figures and movements treated are, first and foremost, of an “exemplary” cast. Like Miss Sontag, all are attracted to extremes: asceticism as a species of spiritual fulfillment in Simone Weil; the arbitrary as a disciplinary device in some of the new wave films; Cesare Pavese and suicidal ineffectuality; Michel Leiris and physical disgust; the theater as interpersonal abuse or “radical juxtaposition” as in Marat/Sade or Happenings.

What supports such a heady ensemble and what shapes many of Miss Sontag’s ingenious turns and twists is her ardent, almost cryptic, concern with “a new, more open way of looking at the world and at the things in the world.” Putting the matter very bluntly, Miss Sontag refuses to acknowledge art as “statement” or “argument,” she demands a “descriptive, rather than prescriptive aesthetic,” and decrying the continued “prestige of ‘realism’,” she rejects the more traditional social or psychological formulation about human nature or the self. Above all, saluting the experimental character of contemporary poetry, music, and the plastic arts, Miss Sontag favors an equally radical transformation of the drama and the novel. In her discussion of Nathalie Sarraute, Miss Sontag states that the coming-of-age of the novel in England and America

will entail a commitment to all sorts of questionable notions, like the idea of “progress” in the arts and the defiantly aggressive ideology expressed in the metaphor of the avant-garde. It will restrict the novel’s audience because it will demand accepting new pleasures—such as the pleasure of solving a problem—to be gotten from prose fiction and learning how to get them…But the price must be paid. Readers must be made to see, by a new generation of critics who may well have to force this ungainly period of the novel down their throats by all sorts of seductive and partly fraudulent rhetoric, the necessity of this move. And the sooner the better.

Reverberating over many battlefields (at one end, the symbolist tradition; at the other, Marshall McLuhan’s electronic wonderland), the call to arms heard throughout Miss Sontag’s volume is fiery enough, but, frankly, not always illuminating. “Indeed,” admitted George Lichtheim gallantly, “it requires a certain degree of intellectual expertise to grasp what she is about.”

IN PART, THE DIFFICULTY can be chalked up to temperament: Miss Sontag suggests contrary components, austerity and voluptuousness, resulting usually in an uneasy truce, as witness the encompassing of Beckett and the Beatles in the programmatic “one culture” of her concluding essay, where both an “excruciating seriousness” and fun and games are held to be “equally accessible” to the participants of the “new sensibility.” A greater difficulty is Miss Sontag’s dialectical constructions. If one gets past the revolving door at the entrance there are sure to be other revolving doors elsewhere. This is especially so in the theoretical pieces, the title-essay and “On Style.” There the bête noire, aside from “genteel-moralistic judgments,” is the proliferation of academic or literary exegeses. “Ours is a culture based on excess, on overproduction…Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there…The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.”

Along that line, Miss Sontag insists that the tank patroling the deserted street in The Silence was not a “phallic symbol,” as Bergman may have intended, and much of his audience thought, but rather a “sensory equivalent” for the rough-house eroticism raging in the hotel. “Those who reach for a Freudian interpretation…are only expressing their lack of response to what is there on the screen.” Nevertheless, as seems a shade obvious, to term one sequence a sensory equivalent of another is also, however subtly, to interpret. Miss Sontag interprets with an eye to structure, while those who cry phallic symbol interpret with an eye to content. Miss Sontag thinks she is responding rightly and directly to a mood, while the others are merely reacting to a clinical phrase. In most of the essays, these distinctions between pure form and impure “meaning” are subjected to around-the-clock alterations, some simply spidery, and some highly significant. A statement such as: “Lévi-Strauss and the the structuralists, in short, would view society like a game, which there is no one right way to play; different societies assign different moves to the players,” has an aesthetic corollary in “On Style”; “Morality is a form of acting…one of the achievements of human will…And as the human will is capable of an indefinite number of stances, there are an indefinite number of possible styles for works of art.” Philosophically, the relativism implicit in both of these quotations seems fuzzy. One may, for instance, reduce morality to a form of acting, and thereby rid ourselves of Sunday School cant. However, if one asks what particular form our acting should take, should it be one of moderation or one of excess, then, I think, we’re back with Aristotle, engulfed by the very ethical concerns Miss Sontag apparently disdains or assumes to be irrelevant.

Advertisement

In any case, in dealing with aesthetics per se, and while passionately attuned to the Continental wave-length, Miss Sontag does not adequately confront the contextualist school of Anglo-American criticism, though now and again she garbles a concept or two. When she says “Transparence is the highest, most liberating value in art—and in criticism—today. Transparence means experiencing the luminousness of the thing in itself, of things being what they are,” she sounds, to my ear, like Eliot or Joyce gone beserk in the direction of Husserl. Nor, for all her admirable erudition, is she above landing in a historical muddle. Declaring that since Diderot the main tradition in criticism has been appealing to “verisimilitude and moral correctness,” she not only turns Kant or Coleridge into un-persons, but also, in effect, peddles misleading summaries. Just as there is more to Arnold than civic uplift, there’s more to Zola than naturalism. Similarly, one may assume that sensory equivalent is concrete, and phallic symbol abstract; in practice, it’s not that cosy. The demented husband of Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy, for instances, squashes a centipede against a wall. It is his fancy that the man whom he imagines to be shacking up with his wife is also squashing a centipede against a wall. How is the double image to be understood—as something sensory or something phallic? Or is it to be “understood”? “Ideally,” says Miss Sontag, swiftly seeking salvation, “it is possible to elude the interpreters…by making works of art whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be…just what it is.”

TO AN EXTENT, of course, that’s true of Ionesco, as Miss Sontag shrewdly notes: “It has been said that Ionesco’s early plays are ‘about’ meaninglessness, or ‘about’ non-communication. But this misses the important fact that in much of modern art one can no longer really speak of subject-matter…Rather, the subject-matter is the technique.” To illustrate, take The New Tenant. While a concierge nags and household movers exchange banalities, the detached protagonist watches his apartment become more and more cluttered, until surrounded by cumbersome furniture, assorted mementos, an ancestral portrait, and so on, he is left literally and figuratively boxed-in. The subject-matter of the play—the disintegration of a mind—is expressed not psychologically, but revealed through the physical procedings—in short, through the technique.

That technique—which somewhat resembles a loony version of the “objective correlative”—both the nouveau roman and the new wave film push a step further. Here the tale, the nominal “text,” becomes a pretext for other interests. The real concern of La Modification, says Miss Sontag, “is not to show whether the hero will or will not leave his wife to live with his mistress…What interests Butor is the ‘modification’ itself, the formal structure of the man’s behavior.” Thus, instead of old guard introspective immersion—what Robbe-Grillet has contemptuously dubbed “suspect interiority”—there’s an attempt at phenomenological neutralism: minute events minutely-described, dehydrated dramatics, unresolved endings. A film like Alain Resnais’s Muriel “is designed so that…at any given moment it is a formal composition; and it is to this end that individual scenes are shaped so obliquely, the time sequences scrambled, and dialogue kept to a minimum of informativeness.” Undoubtedly, being so informally formal has advantages. Resnais can (and does) string together a plethora of rhythmic, tonal, and assymetric patterns—all fugitive, but fascinating. Alas, it produces disadvantages, duly acknowledged by Miss Sontag, but then dropped. For while Muriel indeed rests on a set of particulars—an ex-soldier brooding over war crimes committed in Algeria, his stepmother schoolgirlishly resurrecting an old love affair—these particulars are rendered with such utter impersonality, such indifference, that the form of Muriel, the whole atmospheric structure, need not, fundamentally speaking, change at all, even if Bernard’s guilt had to do with drink, say, or Hélène’s mystifying romanticism had something to do with him. Actually, while watching Muriel there were moments when these and other possibilities crossed my mind.

Advertisement

NOW THE FRUSTRATING element in Butor or Resnais, and with the so-called “bare” book and film generally (and Miss Sontag is a vigilant partisan of both), is not the proclaimed dismissal of psychological plausibility (most of us aren’t “plausible”), but rather, through the anti-psychological approach, a kind of reverse-psychology, tending at times towards philosophic abstractions, almost always ensues. The reader or viewer is presented with the rough data of a person or mind, but the data themselves are processed so transiently (“in situation”), that whatever “theme” or “import” may be around is systematically submerged beneath a fluctuating surface. The surface suggests consciousness on-the-run, so to speak, and, as if in answer to the old dilemma, appearance becomes reality, or to use Miss Sontag’s phrase, “a dedicated agnosticism about reality itself.” In method, at least, it is a little like Glenn Gould’s recent performances of Mozart and Beethoven, in which he emphasizes the bass line at the expense of the melodic line. Naturally even for many who favor technical innovations, such procedures are often considered either gimmicky or capricious, and when not that, downright boring. About the latter complaint, Miss Sontag issues one of her humorless sermons, at which she is quite adept, but here she seems to me to be doing little more than begging the question. “The charge of boredom,” she says, “is really hypocritical. There is, in a sense, no such thing as boredom. Boredom is only another name for a certain species of frustration. And the new languages which the interesting art of our time speaks are frustrating to the sensibilities of most educated people.”

A parallel adventure, more or less publicized by Miss Sontag in much the same manner, is the use of indeterminacy as an artistic principle: Nathalie Sarraute’s unidentified conversations, Antonioni’s indirect spatial longueurs, Grotowski’s Theater Laboratory of Poland where actors turn into props, props on occasion turn into actors, an ugly man portrays a handsome man. Though the rewards can be considerable and the varying rationales certainly unique, in the following case, both the reward and the rationale seem slim. The important fact about Flaming Creatures, writes Miss Sontag glowingly, “is that one cannot easily tell which are men and which are women…The film is built out of a complex web of ambiguities and ambivalences, whose primary image is the confusion of male and female flesh. The shaken breast and the shaken penis become interchangeable with each other.”

COMMENTARY of that sort, while appealingly animated, more often than not soon slips into a semantic tangle. Reviewing Vivre sa Vie, after quoting Cocteau’s charming sophism (“In Orphée…I do not narrate the passing through mirrors; I show it, and in some manner, I prove it”), and then after offering her own elaboration vis-à-vis some cloudy passages on the difference between proof and analysis, Miss Sontag arrives at her coup de théatre: “Godard does not show us why, at the end of the film, Nana’s pimp Raoul ‘sells’ her, or what has happened between them, or what lies behind the final gun battle in the street in which Nana is killed. He only shows us that she is sold, that she does die. He does not analyze. He proves.”

Proof presupposes an hypothesis, a demonstration, and a conclusion, all of which may be found in Vivre sa Vie, as well as in a TV commercial. The proof of the pudding, however, is that a causal connection must exist between the three parts, and as Miss Sontag has previously established, “Godard rejects causality.” I think it is safe to say Godard does not “prove” anything, he merely presents—which is what all art does, and which, frankly, is all that Miss Sontag really means, anyway. Again, Miss Sontag’s deduction that Vivre sa Vie is an essay on freedom and responsibility, though dazzlingly proffered, is not, I’m afraid, very convincing. If it is an essay at all, it is an essay in determinism, and Godard’s Brechtian placards at the beginning of each episode, telling us what will happen, only serve to stress the behaviorist character of Nana, who, pauvre type, cannot possibly support the Sartrean sentiments she spouts. “I am responsible,” says Nana. “I turn my head, I am responsible…A plate is a plate. A man is a man. Life is…life.” These statements, within the context of the film, do work, but only in an ironic, improvisational way. The arresting quality of Vivre sa Vie is its stylish, metallic subversion of two established genres; partly it is a mock-documentary partly a mock-lyric. For Miss Sontag, however, Vivre sa Vie represents Nana’s “twelve stations of the cross,” because the film has twelve episodes, and because in it prostitution “has entirely the character of an ordeal,” and Nana does die. Something equally solemn was once uttered by Roland Barthes. La Dame aux Camélias, he said, is “the archetype of lower-middle class sentimentality.” Poor Garbo.

ROLAND BARTHES’S complex critical apparatus, with its backward-and-forward movement (literature, according to him, is both a meaning advanced and a meaning withdrawn), and its perpetual reassessment of creative works through extra-literary disciplines, has, in varying, often contradictory fashion, affected a good deal of Against Interpretation. In “Spiritual Style in the films of Robert Bresson,” the best essay written on the subject, the Barthesian influence is beautifully absorbed, and Miss Sontag evokes an extraordinary interplay of theological and aesthetic motifs, as she defines the development of such notions as “project,” “gravity,” and “grace” from one film to the next. With the celebrated “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” however, Barthes is left struggling with his disciplines, while Miss Sontag explores Linear B. A multi-layered tour de force, and unreservedly commendable if only because it has annoyed all the right people, “Notes on ‘Camp’ ” is alternately or simultaneously a language-game à la Wittgenstein: a repertory of role-playing à la Wilde or Sartre; the genealogy of a particular taste; a tryptich of cultural modes: classic, modern, and the post-modernist “consistently aesthetic experience of the world” known as Camp; a catalogue of pop-snobbery or democratic dilettantism; and a study in the fluctuating rise and fall of minority groups. Also, embedded somewhere in the “jottings,” and badly bruised, are now-and-then glimpses of its eponymous figure, the camping “queen.” Of course, to the general mind, the latter is the alpha and omega of the whole affair. Either that, or someone always “on stage.” For Miss Sontag, though, Camp means much more: a kind of sophisticated non-art, whose primary attributes are exaggeration, frivolity, inversion, and artifice as an ideal. Moreover, it’s a non-art possible only, and increasingly prevalent, in culturally saturated affluent societies. Thus “there are ‘campy’ movies, clothes, furniture, popular songs, novels, people, buildings.” An amorphous conglomeration. But that there exists such a “fugitive sensibility,” which now transcends its homosexual origins, seems to me quite true. (It also, for the most part, seems to me quite silly, but that, I suppose, is beside the point.) I might add, parenthetically, that Miss Sontag’s Camp citations, while exhausting, are not necessarily inexhaustible. The six Sternberg-Dietrich films are certainly camp. But since Ona Munson’s portrayal of Madame Gin-Sling “camps” Dietrich, Sternberg’s Shanghai Gesture, a non-Dietrich film, could be considered camp-within-camp. The Paris production of ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore was campy less for the staging, than for the ingroup buzz concerning Visconti and his two stars, which was truly echt camp. Besides swish-camp, there’s butch-camp. “The Ballad of the Green Berets” is butch-camp or nothing. An example of absent-minded camp may be seen here: “All I’m saying,” says Miss Sontag, “is that there are some elements of life—above all, sexual pleasure—about which it isn’t necessary to have a position.”

THE ULTIMATE CAMP statement is not, as Miss Sontag famously proclaimed, it’s good because it’s awful; the ultimate Camp statement is: it’s good because it’s the end. “To camp,” says Miss Sontag, “is a mode of seduction—one which employs flamboyant mannerisms…gestures full of duplicity, with a witty meaning for cognoscenti and another, more impersonal, for outsiders.” True, but the motivations of the camp personality, puzzlingly neglected by Miss Sontag, are something else. A person camps, a person becomes “beyond belief,” when the everyday experience is no longer “to be believed.” At the heart of the camp personality, whether gay or straight, is an existential problem. Indeed, in the deepest sense, the whole spirit of Camp is really the existential situation turned on its head. Authenticity, dread, despair—these are the woebegone concepts which have engendered the contemporary version of Camp, and in reverse fashion shaped its life-style. Miss Sontag’s controversial remark is correct only if it is inverted: One is drawn to Camp not because sincerity is “not enough,” but because it is “too much.” For the camp temperament, the only possible solution to the intolerable problem of sincerity or of authenticity is to be deliberately insincere, to exploit, to “enjoy” the unendurable. And it is just that which gives Camp its “outrageous” aspect, and all of Miss Sontag’s intricate palaver about a certain sensibility incarnated in a “woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers” is merely an incidental manifestation of it. “Here and there,” says the author of Beyond Good and Evil, “one can find a passionate and exaggerated adoration of ‘pure form’…Let no one doubt that anyone who needs that kind of cult of surface-things has at some time or other unhappily reached beneath the surface. Perhaps there is an order or rank, even, in these burnt children, these born artists who can find pleasure in life only in their intention to counterfeit its image (to take slow revenge on life, as it were)…”

The provocative, fervid author of Against Interpretation has looked beneath the surface, has grappled with the age’s crise de conscience, and like the younger generation for whom she speaks so forcefully, so dizzily, is now fed up. The message is clearly stated in her paraphrase of Norman O. Brown’s critique of Freudian dualism. “We are not body versus mind, he says; this is to deny death, and therefore to deny life. And self-consciousness, divorced from the experiences of the body, is also equated with the life-denying denial of death…What is wanted…is not Apollonian (or sublimation) consciousness, but Dionysian (or body) consciousness.” The influence of the social sciences and psychiatry, says Miss Sontag elsewhere, has persuaded more and more people to view themselves “as instances of generalities, and in so doing become profoundly and painfully alienated” from their own experience. The way out is through the pursuit of autonomy and a trans-moral intermingling of life and art. Pan-aestheticism, it seems to me, is what is being preached, and to think of it as a failure of nerve is simply to indulge an irrelevant jargon. Miss Sontag’s “new sensibility” is the temper of the times: Art “as an instrument for modifying and educating sensibility and consciousness,” Art “as a kind of shock therapy for both confounding and enclosing our senses,” Art in which technology is not looked upon as a threat and there are “sensory mixes” and “programmed sensations,” and Art where ideas, as in Marat/Sade, “may function as decor, props, sensuous material.” Still, something else seems to be waiting in the wings, a competitor:

“Pot is THEATRE,” exults someone in a recent issue of City Lights Journal. “You yourself are an actor, if you muff a line so what. All situations are scenes, all places are sets. All objects are props. They squirm, how can you take them seriously? One thing turns into another, a clock peels…A shoe comes on like a substance. ‘I’m all shoe,’ it warbles, shuffling along on the floor…”

Miss Sontag in wanting to widen the boundaries of taste and of consciousness, in wishing to drop deadening distinctions between “high” culture and “low” culture, is perhaps not radical enough. Perhaps what pan-aestheticism ultimately points to is its own end. “No more masterpieces!” shouted Artaud. No more arty substitutes of any sort! may well be the next chant. Every creator for himself.

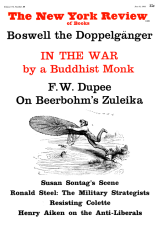

This Issue

June 9, 1966