In response to:

The Shape of Things to Come from the August 21, 1969 issue

To the Editors:

Professor James Ackerman’s criticism of my book Beyond Modern Sculpture (August 21) involves a number of misinterpretations.

First, by insisting that I see all formalist sculpture as derived from the appearance of scientific models he leads the reader to believe that I have stuffed a great deal of art into that narrow category. The point is made that formal models, as a class, possess characteristics that differ from those of representational models; consequently scientific models are only one type of formal model. This oversimplification accounts for Ackerman’s confusion when “nonscientific” examples of Formalism are included in the text.

In a subsequent chapter on Minimal Art the reviewer suggests that I personally support a phenomenological approach to art criticism and he is perplexed that I do not use such a method. My intention was to explain its use; in no way do I endorse it personally.

Ackerman’s real grudge with the book stems from two impulses followed by most trained art historians: one is predicated upon the hope that if we do not contemplate the effects of technology upon art, such heresy will vanish and scholars can return to judging art for art’s sake; or if new art defies the mold of Renaissance or Post-Renaissance connoisseurship, it fails to exist as art and is consequently beneath discussion.

But the nexus of Ackerman’s argument is that my concept of history is faulty. The most dumbfounding statement in his review is “Burnham is Heinrich Wölfflin and Alois Riegl reincarnated.” Can he be serious? My book attempts to refute the idealistic posture of those two historians; it rejects Wölfflin’s cyclical theory of style, and style itself as a primary means of dealing with modern sculpture. In no way does its thesis depend upon the linear and idealistic framework of Hegel’s esthetics and historicism. How then am I linked, in Ackerman’s mind, with these thinkers?

He assumes that my historical model is based upon goals. To understand Ackerman’s position one must be aware of an essay of his in several versions which attacks the use of teleological assumptions in shaping stylistic analysis. But what he fails to distinguish is the difference between Wölfflin’s tenuous theory of stylistic repetition and my view, which is implicitly that no teleology is necessary to prove influence and that technology has rendered the apparatus of connoisseurship obsolete, including Ackerman’s modified adaptation of stylistics.

One might more profitably ask why a teleological explanation of biology and historical events was so necessary to nineteenth century science and philosophy. The reason is simply that no theory accounted for the steadily evolving complexity of human development—without the aid of some premeditated pattern. Yet within the last two decades scientists concerned with the development of self-organizing systems (both physical and symbolic) have begun to explain complexity and diversity without the aid of a teleological mechanism. In inorganic growth, organic evolution, and problem solving complexity may stem from simple forms purely through the aid of random processes. Direction is provided by the relative stability of new forms—be these molecules, social systems, or ideas [see Herbert A. Simon (1969) “Evolution of Complex Systems” in The Sciences of the Artificial (Cambridge: MIT Press) pp. 88-118].

So when Ackerman accuses me of dredging up a nineteenth-century theory to support present developments, he is tilting with a dead issue. My book rests upon the assumption that science and technology are tremendously powerful self-organizing processes which affect everything in their wake.

The central thesis of my book (finished in 1967) is that we are moving from an art centered upon objects to one focused upon systems, thus implying that sculptured objects are in eclipse. Ackerman glides comfortably over this central premise. But it would seem a very preliminary test of the book’s validity would be to compare its thesis with recent events in the art world. For one thing, exhibitions in antiform art, large-scale environmental art, ecological art, and conceptual art have become fairly common. A number of critics have seriously discussed the question of the end of art objects. Dialogues between artists and scientists have grown, not diminished. Also the suspicion has increased that our life-style and uses of technology more fully reflect our esthetic deficiencies, than all the formalist fears about the demise of “high art.”

Through his writings Ackerman has insisted that “durable standards of judgment,” “experience worth having,” “quality,” “tradition,” and “content” are the real keys to evaluating contemporary art. Of course if delectation is the historian’s primary function, then Ackerman’s insistence that “What matters is whether we discover in works of art an experience worth having” becomes the only reasonable purpose for writing an art book. Suppose a writer were to play down the usual tools of the art historian and, instead, dwell upon “experience worth having,” then by what means would he convey these experiences? Obviously there is no way to convey such information. Invariably the historian deals with facts, descriptions, and most fallibly with opinions….

Jack Burnham

New York City

James Ackerman replies:

I’m sorry my description of Mr. Geist as “a student of the artist” was ambiguous; I meant it in the sense of “one who studies the work of” Brancusi. Several people—Mr. Burnham included—have written to say that Mr. Geist’s book was unjustly treated in my review, and I see now that they are correct: I should at least have expressed my belief that it is the best book on Brancusi, and that its catalog is a most important contribution.

Mr. Burnham and I do indeed differ on the points he raises and, as a result, we may both misinterpret each other. But the issues have been adequately presented in the book and in the review; they are interesting ones, and I’m sure I should only confuse them by attempting to respond further.

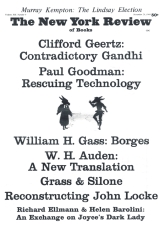

This Issue

November 20, 1969