When Kingman Brewster, Jr., boarded a plane on Monday, May 11, to lead a large delegation of students, faculty, and members of the Yale Corporation to lobby in Congress against the expanded war in Southeast Asia, one sensed that a new alignment of forces was taking place in American political life. It now seems conceivable that the bankers and business executives who comprise university corporations will soon be occupying buildings and circulating petitions alongside students and faculty if the government does not curb its extraordinary appetite for war.

It is too soon to say how fragile or permanent this new solidarity between liberals and radicals, between students and administrators, will be. What is certain is that the first of these alliances was made at Yale, not over the issue of the war but over the infinitely more divisive issue of the Black Panther Party. More than anything else it was the result of that combination of pluck, diplomacy, and conscience which some Yalies refer to as “Kingman Brewster’s Ivy League Machismo.”

Brewster provided a model which appears to have prodded dozens of other university administrators, during the past weeks, to deny their neutrality in a time of crisis, and to speak their conscience. “Perhaps all universities should be on strike,” a Yale professor said the week of May 10, “except Yale. We’ve accomplished too much in the past weeks. We have done here on a small scale what we should be doing in society at large.”

It was ironic that Yale’s moment should have come on College Weekend, the first weekend of May, which is matched only by the autumnal Harvard-Yale events in bucolic and erotic expectations. For decades it has been the weekend to watch crew races and lacrosse matches, go to the beach for the first seaside outing of the year, drink too much at cookouts, take your girl to the spring prom, make love to her by the polluted banks of the Connecticut River. This year, the mood was different. “There’s all this talk about dying,” a Yale senior said to me the week before the May First rally supporting the Black Panthers. “After all in Chicago and Paris there were only billy-clubs. On May Day there’ll be guns. I’m going to the rally, but it scares the shit out of me.” He added, with that strange mixture of terror, Old Blue loyalty, and black humor which pervaded the Yale campus during the week preceding May First: “Of course we’ll take our hi-fi sets out of town before we die.”

What is surprising about the story is Yale’s long innocence. It had been known for almost a year that nine Black Panthers would be put to trial in the New Haven courthouse, a stone’s throw away from the Yale compound, for the murder of their “brother” Alex Rackley last spring. For some months it was known that an immense rally supporting the Black Panther Nine would be held in May on the New Haven Green. In mid-March a white radical group connected with the Conspiracy Seven, and calling itself the Panther Defense Committee, set up shop in New Haven. The rally was being organized by a fringe of the Movement whose dedication to nonviolence was unclear; and its following might well include young radicals whose style of protest, in the past six months, has left deeper scars on the Movement than Agnew’s diatribes have done.

Yet the first two weeks of April dragged on in the somnolent routine of spring classes, with a good portion of the students remarkably ignorant about the body that had been found in Middlefield Swamp in May 1968, comfortably aloof from the trial put in motion by the discovery of Alex Rackley’s corpse. Between Nixon’s November 3 speech and the recent Cambodian crisis, the Movement seems to have been chiefly stirred by events occurring in two courthouses: the Federal Courthouse in Chicago and the State Courthouse in New Haven, which had in common the defendant Bobby Seale, and which called into question, more acutely than before, the quality of justice meted out in this country to blacks and to political dissidents.

Yale’s awakening on April 14 was as swift as it was late. It occurred in the Grecian-columned courthouse a few hundred yards away from the Yale compound, when David Hilliard, Chief of Staff of the Black Panther Party, and Emory Douglas, its Minister of Culture, were given contempt of court sentences of six months for reading a note in court. This event—which suffers only minor modifications from different eyewitnesses—can be described as follows:

Defense counsel Charles Garry handed Hilliard a note from Bobby Seale. Hilliard read it in a whisper to Douglas who was seated beside him. A court officer told Hilliard to stop speaking and put his hand on Hilliard’s shoulder, in what Hilliard interpreted as an attempt to reach for the note. Hilliard stood up and began struggling with the marshal. Douglas, exclaiming “Take your hands off that man,” stood up to assist Hilliard. Court officers surrounded the two Panthers and forced them to the center of the courtroom where they were handcuffed by state troopers. Judge Mulvey, ignoring a plea by Charles Garry to speak for the defendants, immediately sentenced them to six months’ imprisonment for contempt of court.

Advertisement

The campus was suddenly electrified. An editorial in the next day’s issue of the Yale Daily News had this comment: “In view of the events of the last two days, we believe it is mandatory that the entire Yale community examine its relationship to the Black Panthers and the Rackley murder case for the days and the weeks ahead.”

Since the political ideology of the 1970 Yale News is considered “Bob Finch liberal” by the moderate part of the student body, and “liberal Reaganite” by its radicals, it is not difficult to imagine the rage and pandemonium that prevailed in the first student meeting held on the evening of April 15, the day after Hilliard and Douglas were jailed for contempt. Among the milder courses of action suggested: occupy Woodbridge Hall, kidnap Kingman Brewster, shut off the New Haven water supply. A more direct tactic was offered for the imminent May Day rally by Tom Dustou, a Yale dropout and a chief coordinator of the Panther Defense Committee. “Give me some money and I’ll buy guns!” he screamed. “I’ll stand at the Green and distribute them!”

An exotic proposal was brought to the floor by an overwrought law student, who suggested mass suicide: Let each person there be allotted a number, he said, and then each day for the following month the person whose number was drawn would give up his life in support of the Panthers.

“Why die?” a student piped up in the stunned silence that followed.

“To die like a Panther, to die like a man,” the future barrister cried.

The meeting dissolved in an apotheosis of radical guilt and threats of burning down the university, with a vote for a three-day moratorium of classes and a demand that the Yale Corporation donate $500,000 to the Panthers’ legal defense fund.

The campus simmered for several days, with various classes in the humanities and social sciences devoting their classroom time to talking about the Panther trial. It grew more restless over the weekend after Douglas Miranda, the nineteen-year-old New Haven area leader of the Black Panther Party, urged a large meeting of students to strike in support of his brothers. “Take your power and save the institution…. You can stop the country from using the courts as fascist tools…that Panther and that Bulldog gotta get together.”

Two days later Judge Mulvey agreed to restore David Hilliard’s freedom, after he apologized to the court, attributing the scuffle of the previous week to “a misunderstanding.” This did not placate, but heated Yale’s emotions. The students had flexed their muscles, and felt that it was their political pressure that had moved the Judge to commute the Panthers’ sentences. “Since we had the power to make him commute the sentences,” so the logic went, “we have the power to make him do still more.” If two Panthers sitting as observers in court could be sentenced to six months for the events of April 14, then how could the defendants themselves expect even elementary justice in the trial still to come? The factual question of the Panthers’ role in Rackley’s death became obscured, their right to a fair trial paramount.

Tuesday, April 21: At a tumultuous rally of 4,500 people at Ingall’s Rink, the Reverend William Sloane Coffin, whose views on Vietnam had placed him at the extreme left wing of the college three years ago, made a plea that students submit to mass arrest on the steps of the courthouse in support of the Black Panthers, a tactic which struck the students as old-fashioned. The clenched fists of the students rose in the air when David Hilliard, freed from jail after having served a week for contempt, closed his speech to the students by shouting “Strike, strike!” The students returned to their residential colleges to vote on the issue. Nine of the twelve colleges meeting voted that very night to strike and to open their facilities to out-of-town demonstrators on May Day. The remaining colleges—Pierson, Trumbull, Timothy Dwight—voted the following day. A Strike Steering Committee was formed with one representative from each of twelve residential colleges and the graduate schools. The shutdown of Yale began the next morning, with some 70 percent of students staying out of class. (The attendance was considerably higher in the sciences, and microbiology was said to go on as usual.)

Advertisement

At Yale’s twelve residential colleges numerous referenda were taken, resolutions voted, committees formed. Throughout the following weeks, the colleges remained the organizational units of the strike. It is the autonomy of these units, Yale’s uniquely decentralized cellular structure, which must be given a great deal of the credit for the amazingly harmonious way in which the college prepared for May First. For even in the more radical students there is a tribal Old Blue loyalty to the residential college as well as to the university, a sense of community and commune. “I have some radical types here who’d take terrific risks charging up the Green,” Trumbull Master Kai Erikson said, “but who have a strange affection for their college.” And the council of masters whose power Kingman Brewster has vastly enlarged in the past year—was able to work out a highly efficient liaison between the students and the administration. The new political alignments of liberals and radicals, of faculty and students, taking place at Yale and elsewhere in the spring of 1970 had been clearly shown when Yale’s council of masters had unanimously voted, the day before the students voted, to open their residential facilities to the unpredictable visitors expected on May 1.

An even clearer sign of the new alignment was apparent at the college faculty meeting called by Kingman Brewster on Thursday, April 23, to consider the students’ vote for a moratorium. Brewster handled this with the pluck and shrewdness with which he had, in previous years, supported the creation of a strong Afro-American studies program; defended the rights of William Sloane Coffin; limited credits available from ROTC training programs; and encouraged the placement of students on key Yale policy committees. Brewster knew the way the wind was blowing and tacked with it, preserving his position by closing ranks with students and blacks and minimizing dissent against the administration.

Foregoing the usual procedure, Brewster took the unprecedented step of yielding the floor to the black faculty without so much as one opening remark. Professor Roy Bryce-Laporte, the head of the African Studies program, read a resolution drawn up by the black faculty which supported the students’ vote for a moratorium and defined the university’s responsibility to New Haven’s black community. There was a discussion of an hour or so. Then Brewster took another extremely unconventional step by calling for the question to be moved, instead of waiting for a member of the faculty to call it. The black faculty’s resolution—with only one modification of substance—was adopted by a voice vote whose margin is estimated as three-to-one by some observers, six-to-one by others. The only important rephrasing of the black faculty’s original resolution occurred in the following sentence where the original text is in brackets: “We support, and we call on other members of the Yale faculty to support, the issuance of a directive to all persons affected, stating that the normal [functions] expectations of the university be [surrended] modified.”

Other demands—left intact—urged support for a national conference of black organizations to be held at Yale to discuss the “issues of political and social repression”; proposed the establishment of a commission with strong black representation which would have a veto on any of Yale’s land expansion programs; and asked for the establishment of a fund to deal with any financial problems that might arise from the student moratorium. “It was an eerie meeting,” a young faculty member recalls. “The conservatives were there with numerous resolutions, and they could have spoken up, but they never did. It was partly out of respect and loyalty to Brewster, partly because of the old problem of white guilt….”

The dissident faculty spoke later. Professor Jager of the Philosophy Department called the meeting a “Munich” because of its excessive haste. Much of the dissident faculty—some of them concerned with preserving the role of the university as a place of learning where questions of social action would not excessively intrude, others alarmed by the potential destructiveness of the May First visitors—wanted Brewster to close up Yale in the face of the May showing concern. Early in the week there was a new sense of urgency. It was rumored that the Panther Defense Committee had appointed a totally inexperienced eighteen-year-old girl, a freshman at Yale, to be head marshal for the rally. A Safety Committee of seven Yale students and seven faculty members was hastily formed to monitor the work of marshals and handle other logistical problems. (Faculty on the Safety Committee included David Barber, Peter Brooks, William Sloane Coffin, John Hersey, and Kenneth Keniston. Along with Ken Mills, Kai Erikson, Robert Jay Lifton, and two Law School professors—Elias Clark and Abraham Goldstein—they were the faculty members who would do the most to keep the university cool.)

Meanwhile, a continuous bull session proliferated in the common rooms and sunny quadrangles of the university. Along with innumerable talks on the issues of the Panther Nine’s trial, there were forums on the Law of Conspiracy, on the Psychology of Racism, on Language and Revolution, on Colonization and Race in Plantation America; seminars on the Psychodynamics of Racism and Resistance; teach-ins on Urban Community Housing and on Self-Defense for women. There were also teach-outs; some 300 Yalies cut their hair and shaved Clean for Gene style in order to canvass the New Haven community and discuss the issues of the Panther Nine’s trial.

What was happening? The students and teachers at Yale were touchy about the words one used. It was not a “strike” or a “shutdown”—even “moratorium,” a slightly more acceptable word, was not adequate. Kai Erikson of the Sociology Department favored the word “redirection.” Kenneth Keniston stressed that “strike” was an early twentieth-century term totally inadequate for a situation where students were learning at such a furious pace: “We’re trapped in early twentieth-century language,” he said, “to describe a situation totally different from anything that’s happened before on a campus.” Even the word “liberated,” which in other university crises had signified the occupying of buildings, was used at Yale to designate those colleges which voted to open their rooms and dining halls to the May Day visitors. (The only “unliberated” college remained Berkeley, whose master, the economist Robert Triffin, was showing less ready hospitality than were the other masters.)

At a press conference held two days before May Day at the Panther Defense Committee headquarters, it was already evident that the crucial responsibility for maintaining calm rested on the Panthers’ shoulders, and that they were calling for nonviolence as clearly as their language allowed them to. The Defense Committee is on Chapel Street, incongruously set into the block that parades New Haven’s most fastidious Ivy League sartorial goods. Anne Froines and Tom Dustou, chief coordinators of the Panther Defense Committee and of the May Day rally, and Big Man, the Panthers’ Deputy Minister of Information and editor of the Panther magazine, sat on three narrow chairs under harsh overhead bulbs. Big Man—some six feet and two hundred and fifty pounds—has a broad and thoughtful face. Aside from the expected litanies—“a pig is a pig is a pig, no matter what shape, size, or color”—he made a clear plea for nonviolence on May first. “We don’t want anarchism; we don’t want rampaging through the streets. We want organizing.” He gave unexpected praise to Yale students for “cutting their hair and going out to get support from the middle class.” He was cool and witty during the question period.

“Is there any concern on your part that any large organization or group coming into town would constitute a threat?”

“Just the National Guard.”

“What is your position on Kingman Brewster?”

“I don’t know anything about the man.”

Anne Froines, wife of John Froines of the Conspiracy Seven, is delicate and pallid-skinned, with the pinched air of a conscientious nun.

“Mrs. Froines, are you satisfied with Yale’s reaction so far?”

“I won’t be satisfied until the university is run by the students and the Panthers are free…. The struggle at Yale is in part inspired by a realization of what this trial is about…. We are interested in seeing the Yale student struggle taking place and continuing.” Anne Froines’s only relationship to Yale is that John Froines once took a doctorate in chemistry from the university. The white radicals, throughout the week, stressed struggle, while the Panthers stressed calm. Tom Dustou, who had earlier wanted guns for the Green, did not talk; he is bearded, with glazed and humorless eyes. He is a former member of the Patriot Party, a lower middle-class white radical group who copy their tactics and rhetoric from the Panthers, and whose slogan is “Stop Thinking.” They relentlessly purge their members for “too much ego” and “too much subjectivity.” (“I miss the old SDS,” a professor said to me during the May Day crisis. “They were so predictable, dealing with them was like shadow boxing. These new groups are so mysterious….”)

Perhaps it is symbolic of the new political alignments on campuses that Yale’s crisis this spring was one of the few in five years in which SDS has played no official role. SDS leader (PL faction) Carl Zenger, who had been Yale’s first visible radical in the late 1960s, had been called a pig by the Panthers for not putting the problems of the black community uppermost, and was lying low through the April days. Every afternoon at Beinecke Plaza, a strike rally was held around the ten-foot-high Oldenburg lipstick sculpture, which outlines itself incongruously against the World War I battle names engraved on the Doric pediment of Wolsey Hall: “Thierry, Somme, Argenteuil, Marne.”

“We’re going to have a little guided tour of the university,” an SDSer yells into the microphone, “first we’re going to tour the Social Science site, where they’re planning to breed some more capitalist managers, then we’re going to tour the place where they want to rip up some more buildings to build an art gallery…. We’re going to tour the university down!” A few “right on’s,” much shrugging of shoulders. Shortly before at the Beinecke rally, when a Black Student Alliance member had pleaded for nonviolence, there had been a wild ovation. The number of Yale students who wanted to bring the university down was clearly small, and quite powerless. The threat, this time, came from the possible violence of the outsider, from the left’s supposedly lunatic fringe, which was thought to be gathering ominously in New York and Boston. And it was the fear of this mutual enemy which held the university together.

It was ironic that the man most credited by students for keeping the college cool should be Yale’s most radical faculty member. Associate Professor Ken Mills of the Philosophy Department, born in Trinidad, is a tall, lithe, Oxford-educated scholar with an Afro hairdo who looks as if he might be the Panthers’ Minister of Fine Arts. He is described by his friends as “a radical looking for profound historical change, not for protest or ego trips.” He is totally respected by the Panthers, and is strongly opposed to building seizures and similar tactics because they are “played out politics,” leading, as they did at Harvard and Columbia, to setback after the bust. And he has taught much to radical students about the necessity of making well-timed, strategic alliances with liberals.

“The phrase ‘to hell with liberals’ is foolish,” he told me in his blend of Oxford British and West Indian. “People spout Mao Tse-tung as a head trip. If you start looking at Mao’s categories of primary contradictions, secondary contradictions, and so on, you have to ask yourself a serious question if you’re on the left: is your main enemy the liberal or the conservative forces? The radicals have always this fear of cooption, but you cannot get coopted if you know what you’re all about. The black faculty did not get coopted at the faculty meeting. They knew what they went in for and by and large they got it. For several reasons the president of the University joined them, but this is not because he coopted their efforts, but because of his own set of strategic plans.”

In one of the few interesting speeches of the May Day weekend, Tom Hayden would compare Kingman Brewster to Sihanouk because of his efforts to maintain neutrality while sheltering radicals. He stressed that the neutralist sanctuary for the Movement in New Haven would be used for increasingly larger and stronger attacks on the court system, with rallies increasing in size as the trial progresses. (The next is scheduled for July 26, to coincide with the Cuban celebration.) New Haven’s days of unrest are not over.

May Day: A morning mist hangs over the city, whose streets are chillingly empty and quiet. One-third of the student body has left. I am reminded of the first war weeks of 1939 in Paris: the stores boarded up by cautious merchants, the families sent out of town, the first-aid station signs at the gate of every college. The out-of-towners begin to arrive, in surprisingly small numbers, many of them easily distinguishable from the most eccentric Yale students. There are emaciated macrobiotic types with hair down to the waist, motorcycle gang toughies, kids dressed like Algerian paratroopers, complete with water canteens, knapsacks, and gas masks.

I walk down Grove Street with two girls from Long Island who admit that they are “scared shitless” by the National Guard, but are determined to stay because “it is our duty to help keep things nonviolent.” The crowds, they say, will be much smaller than predicted. Even the head of Harvard SDS is said to be staying away because he is “scared shitless”—the words come out throughout the week with numbing repetition—of the bloodbath. Yet as they talk I detect a peculiar joy, an ambivalence of thrill and terror, in the girls’ eyes. A larger proportion of girls than of boys is supposed to have stayed at Yale. Is it their greater romanticism in the face of danger, their Florence Nightingale instinct of taking care of those who might be hurt? In between talk of guns and bloodbaths they launch into fastidious Home Ec descriptions of how the weekend crowd is going to be fed.

“The student body voted to go on a low subsistence diet to accommodate the visitors,” one of the girls says with pride. “We’re going to serve 170,000 meals over the three-day period. We’re having two meal shifts a day, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and 4 p.m. to 10 p.m. Familia the first morning followed by rice cooked in soya sauce, lox and bagels the second morning with franks in the evening….” On the way to the press conference at Center Church held by Panthers and members of the Chicago Conspiracy we pass through Branford College, where students and visitors are being fed familia (a commune gruel) as at a trough, scooping up cupfuls of bran-date-sunflower-seed-and-matzoh mixture out of vast metal vats. The girls talk about death, the National Guard, and how decently their parents are behaving back in Great Neck.

The press conference is one of the more surreal scenes of the weekend. Hayden, Froines, Dellinger, Davis, Wiener, Rubin, and Hoffman stand banked by cameras below the delicately curved altar of the genteel 1810 Congregational Church. Above them, in front of the altar, is a choirboy contingent of Yippie supporters softly waving their flag of marijuana leaf and red star rampant on a black field. The flags are furled onto soft rolls of cardboard; for law school students had spread through the colleges the night before, warning students and visitors that definition of weapons would be strict, and might include Afro combs, belt buckles, and flag staffs.

Dellinger makes a guarded plea for nonviolence. “We must not let Nixon and Agnew prod us into false violence.” He pledges to return to New Haven. “From now on the Chicago Eight will be based in New Haven!” (“One, two, three, many New Havens” has become a weekend slogan.) “Revolutionary youth, we’ve got to educate that Brewster,” Hoffman yells out. “Brewster is saying that he does not want another Woodstock here but we won’t let him separate our politics from our culture! We will not let America devour its youth! The Panthers have their breakfast for children program, the establishment has its children for breakfast program!” Strident, Day unrest, lock every gate, and send the students home. “I was immensely cheered that my immediate fears proved groundless and that Kingman Brewster’s plan was effective for cooling that potentially explosive weekend,” Robert Brustein, Dean of the Yale Drama School, would say after May Day had proved calm. “But in the long range I am worried about the impulse to induct the university wholesale into the service of social action, even during crisis, for this is bound to have dark consequences for the future of academic freedom, artistic variety, and open scholarship.”

It was also at this meeting, between the presentation of the black faculty’s resolution and discussion upon it, that Brewster made the following statement, which deserves to be quoted in full because of the misunderstanding that fragmented quotations from it have caused.

I would like to make a few remarks about what I take to be the two issues presently disturbing all of Yale. The first is the trial of the Panther members; the second is Yale’s relation to the community.

My statement of last Sunday tried to make it clear that Yale as an institution as well as myself personally have a very real concern for the fact of justice and the confidence in justice in our own community. No principle of neutrality should inhibit the university from doing whatever it can properly do to assure a fair trial. The university is ready to meet the expenses or make available the faculty time which might be involved in the monitoring of the trial, reporting on its developments, and reviewing its fairness, not just for the benefit of the profession but for the benefit of the public.

The university cannot, however, contribute to the costs of the legal defense of any defendant. We could not use funds given to us for the tax deductible purpose of education and turn them over for the benefit of a particular person where a gift would not qualify for a tax deduction. This is an absolute legal barrier to any use of university resources for a defense fund; the same, I am advised, would be true of bail funds for a particular person.

None of these strictures, however, should inhibit any one of us, in his individual capacity, from declaring himself on the issues of the trial and its fairness, nor from contribution as he sees fit for the benefit of any individual defendant or member of his family.

So in spite of my insistence on the limits of any official capacity, I personally want to say that I am appalled and ashamed that things should have come to such a pass that I am skeptical of the ability of black revolutionaries to achieve a fair trial anywhere in the United States. In large measure the atmosphere has been created by police actions and prosecutions against the Panthers in many parts of the country. It is also one more inheritance from centuries of racist discrimination and oppression.

As a private citizen I would also say, however, that doing anything to inflame the community would be the worst possible service to the defendants. Their chance of being able to raise and prevail on the many real legal and constitutional issues raised by the arrest and indictment would be smothered if political passion were allowed to dominate the scene of the trial. All of us have a responsibility not only to the community but to these defendants and their families to do everything we can to see this does not happen. The first contribution to the fairness of the trial which anyone can make is to cool rather than heat up the atmosphere in which the trial will be held.

It is said at Yale that if Kingman Brewster had seen the black faculty’s resolution before the meeting—or at least had been aware of its reasonable tone—he might have prepared a less powerful statement. But perhaps it is precisely the boldness of his stand—its dose of moral overkill—which enabled Brewster to bring about an alliance not only between the college’s black and white communities, but also between its liberal and radical factions, something no university president had been able to do before. And while some of Yale’s more cautious professors, alumni, and trustees were angered by reports of his statement, many of these united behind him when the Vice President stated that he did not feel that “students of Yale University can get a fair impression of their country under the tutelage of Kingman Brewster.”

Next to Agnew’s attack against Brewster’s position, few things irked the people I talked to at Yale more, during the week preceding May Day, than the mistaken notion that Yale students were demanding the cessation of the Panther Nine’s trial. In the final five-point list of demands made by the Strike Steering Committee in close cooperation with the Black Student Alliance, the phrase about the trial went as follows:

“The Black Panther party is and has been the victim of political oppression and police bias. We, the students of Yale university, believe that these conditions subvert the legal system as an instrument of justice and preclude a fair trial for the New Haven Nine. We call upon the Yale corporation and the American people to recognize this and join us in demanding that the State of Connecticut end this injustice.”

An earlier version of this demand had indeed asked that charges against the Panther Nine be dropped but had been revised because it found little support. According to campus estimates, less than 10 percent of Yale students would have voted for it. Yet a majority of the students had a gut sympathy for Chaplain Coffin’s Antigonian statement that it was “legally right and morally wrong” to bring the Panthers to trial. It was a statement as distorted, when quoted out of the context of the Sunday sermon in which it had occurred, as the isolated fragments of Brewster’s statement to the faculty. The phrase had not even been coined by Coffin, but, as he pointed out, by a perturbed juror at his own trial who had said that he felt it was “legally right and morally wrong” to convict the Boston Five.

The opacity of Coffin’s statement was due, in part, to the fact that he had lifted a phrase out of a trial concerned with issues of political dissent and tried to apply it to the vastly different context of a murder trial; and, in part, to its centering on the tenuous issue of collective guilt: “I say legally right, but morally wrong, because while in the eyes of the law the defendants may be proved guilty as charged, in the sight of God all of us conspired to bring on this tragedy—law enforcement agencies, by their illegal acts against the Panthers, and the rest of us by our immoral silence in front of these acts.”

What was obscured, in quoting the phrase out of context, was that Coffin was not so much judging as “morally wrong” the fact of the Panthers going to trial. (“I myself cannot judge, or rather prejudge, the defendants of this trial. The evidence is yet inconclusive…[A]s there can be no reconciliation without justice, there can be no salvation without judgment.”) Rather, like Brewster, he was pointing out the immoral—because illegal—treatment of the Panthers by the police and the courts in the past, and questioning the dubious quality of justice which would be possible for them within American society. It was a statement which had in moral fervor what it lacked in intellectual clarity, and which was met with particularly unanimous approval by Yale’s divinity students.

The other four demands presented by the Strike Steering Committee called for the establishment of free day-care centers for Yale employees; stopping construction of the Social Science Center because it would serve “to create a business and governmental elite which exploits the people”; the establishment of adequate wage and workmen’s compensation for Yale’s personnel; and a curb on Yale’s expansion plans in order to stop depleting New Haven’s housing market. The link between the Panthers’ trial and a concern for the black community was clear enough: Since Yale is helpless to call off or interfere directly in the trial, the least it can do is to show greater interest in the black people of New Haven.

But the students’ alignment behind these two concerns was more complex. Many favoring the strike and supporting the rights of the Panthers showed little interest in the last four demands. Other progressives who had worked hard and long to increase Yale’s sense of responsibility to New Haven—and had met with great indifference—opposed the strike, and were bitter that it had taken a corpse, a trial, and a May Day demonstration to jolt the students. “Do you know what this strike is really about?” a graduate student who felt such bitterness told me. “It is a structuring of time to alleviate the anxiety of May Day, an anxiety compounded of expectation and fear.”

The fear was real. Many students admitted that they were more frightened by May Day than they had ever before been frightened in their lives. A good many faculty members were planning to send their families out of town. Alarmism had been fed by a fire at the Yale Law School library (it is still unknown who set it); by a theft of 245 pints of liquid mercury—an ingredient readily used in homemade explosives—from the Sterling Chemical Laboratory; by reports that guns had been stolen from sporting-goods stores in nearby Newington and Fairfield, and another collection hijacked from a truck; by the arrest of a Weatherman Yale dropout for the possession of already made explosives.

There were rumors that Boston radicals planning to attend the rally had been purchasing guns in Massachusetts; that some 300 Minutemen had reserved rooms in motels adjoining New Haven; that a machine gun had been posted on the tower of Calhoun College; that in the bloody fray caused on Harvard Square the previous week by the November Action group, young radicals dressed as policemen had beaten up kids to incite provocation and were planning to repeat this tactic on May Day. The most ghoulish speculation heard was that if the virology lab on Wall Street was bombed, all its Lassa Fever viruses might spread through town.

Yale students, it was feared, were being used as pawns by a left fringe whose maladroit aping of Panther tactics were alienating not only the liberal faculty but also most of the radical blacks and whites in the college; whatever violence they caused would principally victimize that black community for which Yale was belatedly fanatical shouting fills the delicate white church, and one is reminded of Daley’s cohorts stomping for their leader from the galleries of Chicago’s Convention Hall.

An hour later Jerry Rubin, in tanager scarlet pants, packs them in again in Wolsey Hall. “It’s you, the white middle-class students, who are the most oppressed class of our society! More oppressed than ghetto children or poor whites! You know what college is? It’s an advanced form of toilet training!” Loud stomping, clapping, the kind of wild cheering offered by Lenny Bruce’s audiences.

“We’re everything they say we are! I haven’t taken a bath in six months! We aren’t ever going to grow up! We’re never going to mature! We’re never going to be rational! Fuck rationality! It’s the alcoholics who’re putting the pot smokers in jail! It’s the alcoholics who beat their wives and oppress their kids and invade Vietnam! Telling us to stop smoking pot is like telling Jews to stop eating matzohs!” More wild stomping. “Until you’re ready to kill your parents you’ll remain a consumer society!” The Yale psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, sits through Rubin’s talk taking copious notes.

Rubin’s speech lasts almost to the beginning of the rally, and the rest of the program is a terrible letdown. After the weeks of revolutionary rhetoric, radical soul-searching, and liberal apologies, the talks by Hilliard, Dellinger, and Big Man on New Haven Green have the impetuousness of piped Muzak. The afternoon is beautiful and somnolent. There are an unexpected number of middle-aged Connecticut couples with Joe Duffey for Senator buttons on their lapels. The students lie in the grass, eyes closed, stretching like young animals as the speeches drone on. During an endless translation of Jean Genet’s statement a graduate student sitting next to me yawns and adds, “It is important that we accept boredom instead of getting killed.” As at Mobe’s May 8 rally one week later, one senses as poignantly as the Panthers and members of the Conspiracy—without necessarily drawing the same conclusions—that the days for this kind of rhetoric are over. One also senses a terrible void between the possibility of successful direct mass action—yet undefined—and Rubin’s borscht-belt black comedy.

We first see the National Guard in front of Branford College, lined up three deep. Five hundred Guardsmen have been deployed around the year’s most soporific rally. There is an unreal freshness to their khaki uniforms, water canteens, boots, and grenades, which recalls play uniforms bought for ten-year-olds to wear at birthday parties. They look younger than the Yale students. The children are pitted against each other. A Yalie with an expensive Japanese camera lies on the sidewalk, aiming his lens at the Guard. “Smile, captain, smile,” he says. Across the street, some fifty students ogle, giggle, flash V signs. “I don’t believe it!” a freshman Yale girl squeals. “I never thought I’d see it! I mean it’s not for real! I mean it’s so exciting! And terrifying! And exciting!” “It’s Catch-22,” her companion giggles, clapping her hands.

An hour later we are walking down Grove Street, a Yale girl and I, where a line of Guardsmen lean against the gate of the cemetery. A soldier with a round face, green and trusting eyes, stops us.

“How is it out there?” he asks.

“Dull,” the Yale girl says.

“How many blocks am I from the Green?” he wonders.

“Two blocks away,” she answers.

“I wish I were out there,” he says nostalgically, “or at the beach. I could have been in Cape Cod this weekend if they hadn’t called us out. I love the beach.”

“What’s that you have on your chest?” the girl asks, touching the round tear gas canister that hangs from his breast pocket. “It looks like a Christmas tree ornament.”

“I’m not allowed to say,” he says mournfully. His eyes stare at us, mottled and gentle, from under his khaki helmet.

“I bet you don’t want to hurt us,” the girl says, “any more than we want to hurt you.”

“I’m nonviolent,” he says, and adds, pointing to his gun: “But you see, it’s either this or jail.”

They stare at each other for a few seconds. “Your eyes,” says the girl, “are as green as your uniform.”

“We licked ’em with love,” Bill Coffin said in his Sunday morning sermon following the May Day rally. There was a euphoria of congratulations in New Haven after May Day was over. Kingman Brewster congratulated the Panthers and the police, the police congratulated the student marshals, members of the Yale Corporation congratulated Kingman Brewster for having gambled on hospitality and trust, and won.

But it is a sign of a high political talent of the Panthers who had called the rally had known to keep it cool, and had made the rights of the Panther Nine a cause to which a great university could rally. The Panthers had gone out into the most explosive sections of the city on two weekend nights and blasted through their bullhorns: “Everyone but pigs and marshals off the street.” They had advised gangs of out-of-towners intent on provoking violence to “take the shit out on your own time.” “Stop your ego trips, you weekend revolutionaries,” they had said during the Saturday night fray. “You can get tear-gassed and go home, we have to take the consequences.” And the only slogans which enabled white marshals to calm tear-gassed demonstrators during those weekend nights were “The Panthers don’t want violence” and “The Panthers say go to your colleges.”

The Panthers had taught the weekend revolutionaries that well-timed restraint is a great test of political sophistication. As for Kingman Brewster, in taking a brave, shrewd, and well-timed risk he had taught the university system a lesson that may turn out to be a crucial one for the politics of the Seventies.

During the following weeks Yale, like other colleges throughout the country, would be steeped in the anger and sorrow that followed the slaughter at Kent State. But at Yale there was an added feeling of shock, of identification with the students who had died in Ohio. “Some of our side threw rocks too,” a student said. “We did the same things they did, and they’re dead. If we had come to that kind of a crisis here, Brewster and many of the faculty would have been with us facing the National Guard.”

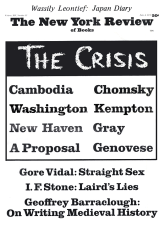

This Issue

June 4, 1970