It had been thought that Arthur Goldberg was one of those great balloons—like Dwight Eisenhower in 1952—subject, of course, to shrinkage over six months in the sun, but with more than enough reserve of air to remain aloft and defeat Governor Rockefeller next November. But he seems already to have begun to leak most alarmingly. The Former Justice of the Supreme Court, the Former Secretary of Labor, the Former Ambassador to the United Nations—an outrider benumbed by these ruffles and flourishes affectionately wondered aloud whether it might not be simpler for provincial chairmen just to introduce him as the Former Arthur Goldberg—was put through the most painful primary night by merely the Former Undersecretary of Commerce and Former Candidate for Lieutenant-Governor of New York, Howard Samuels. The Justice-Ambassador-Secretary sat up until two in the morning, all that dignity hanging over an abyss of humiliation; and he won in the end with only 52 percent of the Democratic vote.

Mr. Samuels, to be sure, had brought to his campaign the carelessness about capital that the very rich seem especially to demonstrate when their own ambition is the object of their philanthropy. His showing must be credited then in some measure to the extinction of romantic illusion in his party: the Democrats of New York seem to be drawn to a candidate these days as women of the eighteenth century were to Casanova, that is, to the man who pays.

But the advantage that almost made the difference for Mr. Samuels was no more in what he spent than in what he promised to do. He would, he kept insisting, be a fighting governor, to which Justice Goldberg was proud to reply that he would be a governor who conciliates. And it was that posture, you finally sense, which caused him to bleed more than he should have and which he seems determined to maintain, with the potential for even more bleeding, all the way along the course ahead of him.

For Justice Goldberg still believes that America is a success. He trusts all parties in their quarrels; and he seeks, with the assurance of finding it, some communality in their interests. That spirit gives him a curious, if rather touching, air of antiquity as he enters a politics where more and more voters feel that what history has put asunder no man ought to try to put together short of the knife. Set aside for the moment the servant and the master: there is nothing in common between the managers of the Long Island Railroad and those they carry these days.

For it is a peculiarly sad moment in history when those qualities in Justice Goldberg which we would otherwise conceive as being most admirable could not serve us worse if they were character defects. There is, to take the most lamentable trait, his sense of duty. He cannot resist any call to sacrifice. It has never occurred to him to be selfish and to do what he wants; he would have lived his life out on the Supreme Court, never so much contented with himself or more contenting to others, if Mr. Johnson had not persuaded him that his country needed him as Ambassador to the United Nations. He ended there earnestly defending in public and painfully striving to correct in private a government which had abandoned him.

Still he carried an intact sense of public duty into the private life this excess of trust had forced on him. His most conspicuous civic effort between then and now was his leadership in forming a commission to investigate the treatment of the Black Panthers by police departments. The results of that experience were painful to him and damaging to the enterprise; and they suggest that the sense of virtue which impels Arthur Goldberg to good works is a reason for their turning out badly.

On December 15, a few days after the police shooting of Fred Hampton, Chicago chairman of the Black Panther Party, Justice Goldberg and Roy Wilkins, director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, announced “a searching inquiry” into Hampton’s death and cases of police conflict with the Panthers in “Los Angeles, Detroit, New York and elsewhere.” The present situation, Justice Goldberg said, “clearly poses the most serious questions, which must be answered and dealt with if Americans of all persuasions are to have continued faith in the democratic process.”

His commission appointed Norman Amaker, an NAACP lawyer, to direct its inquiry. There was some expectation of funding from the Ford Foundation. Since then Ford has backed away; the commission’s straitened staff does its best with no expectation of any funds more generous than those already granted by the NAACP and without even a full-time director at the moment, Amaker having departed in despair. One supposes, as happens with employees, that he will be blamed for its troubles; it is not surprising, as happens with youthful outsiders, that he makes a very good case for blaming certain defects in the splendid impulses Justice Goldberg brought to the work.

Advertisement

Shortly after the committee was formed [Amaker remembers] David Hilliard went on television and said that appointing Goldberg was like appointing the fox to watch the chickens. Eldridge Cleaver said something about Goldberg being a Zionist pig. He asked me to come to his office and expressed his anger at this sort of thing. Didn’t these people know his record? “Do I have to display my credentials?” he asked. And here his friends were asking what had come over him and he was getting the worst hate mail of his life.

There seems to have come over Justice Goldberg thereafter that diminution of spirit which can happen to the best of men when they have tried to do a good thing and are not appreciated. He made little use of his unique eminence which might have persuaded the Ford Foundation to give its grant. His most consequential act thereafter was founded on those reflexes conditioned to respond to his government’s call. Attorney General Mitchell, whose nose for the weaknesses of the well-intentioned must be keener than is admitted by detractors of his subtlety, telephoned the Justice to request an opportunity to explain why his department could be trusted to pursue its investigation of Hampton’s death, without the need for concerned citizens to bother with their own.

So Justice Goldberg settled loyally into his accustomed place as mediator, in this instance between Norman Amaker and Jerris Leonard, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Director

We came pretty suspicious [Amaker remembers]. It was mostly a matter of listening to Leonard. We were only able to raise general kinds of questions. He did say that on the basis of what the Grand Jury had heard so far, he didn’t see how indictments of some policemen could be avoided if the facts checked out.

On that assurance, the Justice Department was allowed to proceed without the interference of more zealous competitors. In the end, the Grand Jury decided that every substantial fact in the allegation that Hampton was murdered by law officers checked out, and proceeded solemnly to indict no one. Justice Goldberg might, of course, argue that, without the pressure of his commission, there might not even have been a Grand Jury finding of fact in this case; but it would be an argument made considerably less powerful by the condition that he has left the commission in not very good shape to exert any real pressure in the future, and by a posture which seems to suggest that any disillusionment these events have brought to him has been less with the Attorney General, the Ford Foundation, or himself than with the Black Panthers.

This experience seems to have made no perceptible mark on Justice Goldberg’s serenity, although, if anything could, it ought to define the perils to be faced by any man who thinks of himself as above all a conciliator in a time when mediation, more nakedly than often before, is increasingly a sitting-down between the wolf and the lamb. Justice Goldberg and Norman Amaker clearly have more in common than the Justice could hope from the disputatious parties he promises to bring together—good intentions and high social purpose for one thing. Yet, when their enterprise withered, Norman Amaker put most of the blame on Justice Goldberg’s vanity—a weakness fairly to be charged to him once we recognize that it is no petty esteem for self but a vast, impersonal vanity about America. But if history is by now so poisoned that even partners can come to think so badly of each other, who could dare still promise to bring enemy to lie quietly down with enemy?

There is, of course, considerable vanity in attendance to the call of duty; you just ought not to take yourself so seriously as to give in whenever someone else tells you that you alone are needed. That habit of duty pulled Justice Goldberg into this latest embarrassment. He had hoped to stand for the Senate, and was pushed to run for Governor by Stephen Smith, executor of those Kennedy properties which look for the moment to have died intestate.

Smith seems to have told the Justice that no one except him could unite and revive the Democrats of New York State. The command which had been offered as an anointment turned out to be obtainable only through painful and almost humiliating fraternal battle. Justice Goldberg could hardly in reason have expected any more comfortable result from having consented to preside over a party whose natural state is tribal warfare. But he had, as usual, given way to his habit of assuming that the parties before him share his concern with public problems and his confidence that everyone present wants to solve the very few of these he thinks remain.

Advertisement

Stephen Smith could not, of course, care very much about public or even party problems, except as they intrude upon that desire to be let alone—a right clearly earned after so many years of service to a family whose tragedies have now left it for the moment with no survivor whose interest can practically be thought of as capable of advancement. As Robert Kennedy’s New York executor, Smith is naturally heir to those suspicions of dynastic ambition which used to hang over his great principal; and he does have that sharpness toward the crew which is unavoidable for anyone whose blood comes from generations of Brooklyn tugboat proprietors.

But it is an impatience aroused not by their habitual failures as mechanics but by their persistence in intruding upon him their personal troubles and frustrations. His stewardship impresses him most for its inconvenience; he can be pardoned if these annoyances were so overriding in him that all the while he was imploring Justice Goldberg to take up the burden of New York State, he was thinking only of removing the burden of its Democrats from himself and imagining a state of things where all these unwanted retainers would be decently employed with no further need to bother him.

But Justice Goldberg could not conceive of feelings so personal, so selfish, indeed so sensible. The public life, for all his experience, remains to him sacred in everything and in nothing profane; it is hard to imagine a private thought of his about an American institution that would differ much from his public speech on an occasion celebrating some anniversary of its founding and the unmixed benefits of its subsequent labors for us all.

This faith in our history as a constant progress toward ever sunnier uplands must make peculiarly disabling the attitude he brings to the confrontation with the national institution of Nelson Rockefeller. Both are exhibits for the illusion of how much improved we all are in this century: Justice Goldberg comes from a labor movement and the Governor from a family which, fifty years ago, were alike objects of the distrust of broad, if not identical, sections of the American public. Now no family is more admired than the Rockefellers and few persons more admired than the former General Counsel to the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Each is a symbol of that disgusting Wilsonian ideal of the institution in the service of the nation.

Yet all this has nothing to do with Nelson Rockefeller who has, like most great figures of romance, by now no more social conscience than a cat, and is indeed so bored with public affairs as to move entirely as his private passions direct him. In 1966, he made it seem quite plausible that he ran for governor largely to keep Mrs. Rockefeller from blaming herself for having destroyed his career; if he carries on now, it may be under no spur stronger than his hatred for John V. Lindsay. His sudden tolerance for President Nixon, his noticeable silence about Vice-President Agnew are put down to calculation; but it seems more likely that the Governor is long past caring about public issues. His politics are not social but domestic: what alternative is there to Nixon, the mere acquaintance, except Lindsay, the intimate enemy?

The notion that eminent personages could go this far beyond the gospel of service is, of course, alien to Justice Goldberg. The contest between him and Governor Rockefeller seems to be, just by itself, enough to justify his feeling of contentment with history; it suffices that one or the other of two persons, each born under circumstances seeming to make elective office unimaginable, will now be governor of New York. The mere existence of such a choice must seem another of those affirmations of the American promise that make who is finally chosen rather beside the point. The republic has already and too far in advance proved itself to Arthur Goldberg.

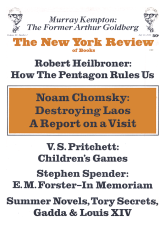

This Issue

July 23, 1970