The faster political evolution proceeds, the commoner becomes a sinister mutation in young men and women: polymorphism of the personality. In Japan, we read, it is frequent for a man in his late twenties to have been successively a docile pupil and son, a national-revivalist fanatic, an armored student stamping through the gas clouds for Marx and Mao, a whiteshirted executive soothing the computers of a new electronics corporation. In West Germany, similar quick-changes of the personality can be observed as the authoritarian, libertarian, contemplative, and engaged modes of life are buttoned on, paraded, and then exchanged. The mutation is defensive: what value, it is implicitly asked can consistency of personality have in a century constructed like an evening of ancient music hall?

To the impassioned revolutionaries of the first years after 1917; such adaptability would appear—had they survived—as merely a development of the craft of groveling fostered by fascism and Stalinism. But their own fate, so often inner emigration followed by defection or death, certainly did not suggest that upright consistency was best suited to ensure the survival of the species. Revolution is a trade in which many have their hour, but very few indeed have their decade, and the hour of revolution is also an indiscriminate rallying together of all kinds of rebels whose real part is soon played. For such people, the next twenty years in the Party were bound to be an anticlimax to the few days in which they shook the world. To have mattered and minded in the international Communist movement in 1920 often meant, for those whose allegiance was really to the revolution rather than the Party, death or defection by 1940. Elisabeth Poretsky’s husband, the Soviet agent “Ludwik,” was offered the chance of going back to normal political work after nearly ten years in intelligence. “What Party work?” he asked. “What Party, come to that?”

All three men whose lives are recorded in these books, “Ludwik,” the German Communist Heinz Brandt, and the libertarian revolutionary Victor Serge, succumbed to the centrifugal force of Stalinism and retreated to the West. All refused to play the chameleon, and fought in their various ways for a purification of the revolution which, they believed, they had not abandoned: it was the revolution which had abandoned them and with them, its proper nature.

One day, a historian bored with period controversy will try to discard both their arguments and the reproaches of those who called them traitors by suggesting that a revolutionary may be judged by the intensity of his contribution rather than by its duration. These men would have found such harlequin fatalism about human effort disgusting. They paid hard for their decision to carry on the struggle. Serge lived in poverty and exile until his death in Mexico in 1947. Heinz Brandt was kidnapped back by the East Germans and released only three years later. Ludwik was murdered by NKVD agents in Switzerland, within months of his break with Moscow.

Heinz Brandt, who now works for the West German metalworkers’ union in Frankfurt, was a “Conciliator.” This was the important faction within the German Communist Party (KPD) which came to oppose Stalin’s “ultra-left” policies at the end of the Twenties. The Conciliators tried to resist the breach with the trade unions and the Social Democrats (“Social-Fascists”) which Stalin forced upon the KPD. The faction had powerful friends: Gottwald, Togliatti, and Dimitrov were (according to Brandt) in sympathy, and in Moscow the Conciliators pinned their hopes on Bukharin. It was useless. The popular front policy came too late to stop Hitler from walking into power past a divided working class, and most of the Conciliators were amicably shared by the murder facilities of the two dictators.

Brandt stayed on in Germany, producing a clandestine news-sheet. He was young and devoted, the son of a lively Jewish family in Posen. His education was his grandfather preaching the “liberating revolution” of Judaism, his father exclaiming that “these Bolsheviki will save the world.” It was his own sudden decision to stay on his feet as the Polish Corpus Christi procession went by while everyone else glared at him from their knees. It was the ever-recitable Berlin of Piscator and Brecht and Heartfield, of Ernst Thälmann and Polizeipräsident Zörrgiebel, of the thirty workers Zörrgiebel shot dead at a May demonstration.

Brandt did not stay at liberty long. He was released after being whipped, kicked, and punched for a night in an S.A. headquarters. The second arrest, when he was caught in Spandau distributing his paper, was more nearly final. Brandt spent ten years in the Brandenburg jail, in Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz, and finally Buchenwald, where he took part in the prisoners’ rising which freed the camp.

Brandt describes the great prison debates among Communists, as the Nazi-Soviet Pact and its consequences sieved out loyalists from rebels. Men later to be powerful in the German Democratic Republic, like Bruno Baum, praised the trick of “unleashing war between imperialists.” Others surrendered psychologically because “I don’t want to be a negator of everything and end up in suicide.” Brandt was among those who lost faith in Stalin and argued for a new form of workers’ party, but after the liberation both sides found themselves under suspicion from the “Ulbricht Group” returning from Moscow. As in West Germany, so in the East: the concentrationnaires who assumed that they would found a new democracy were disinherited.

Advertisement

The most striking part of Brandt’s book is his record, from his experience as a senior official in the Berlin party secretariat, of the year 1953. Only Stalin’s death, he believes, saved the GDR from anti-Semitic show trials on the Rajk-Slánský model, in which Franz Dahlem was cast as the senior victim. There followed the imposition by Beria and Malenkov of a “New Course” upon Ulbricht and their apparent selection of Rudolf Herrnstadt as his successor. But Ulbricht’s way of carrying out his orders was to relax pressure on the middle classes and strike the word “socialism” from the banners, while increasing the production norms of the working class. The result was the workers’ rising of June 17, which forced Soviet tanks onto the streets and paradoxically saved Ulbricht’s position through its revelation of his regime’s weakness.

Brandt’s eyewitness experience of the June days is fairly evidently the source of Carola Stern’s account in her biography of Ulbricht (Praeger, 1965), but his own version is fuller and more suggestive. Admittedly, his belief that Malenkov and Churchill were nearing agreement to reunify Germany on the basis of letting Communism in the GDR “slide to disintegration” is hard to swallow (Brandt is not particularly accurate about events outside Germany). From his record of the origins of the rising, on the other hand, one can construct a fascinating hypothesis: that this was the first time since the Twenties in Russia that the working class of a socialist country rebelled against the introduction of a crudely meritocratic system. It was not to be the last.

The rising was crushed; the promises of the “New Course” gradually revoked. Brandt was among many who lost their posts, and in 1958 he crossed to the West. He was kidnapped back in 1961 but refused to make public recantation, and was relegated to the penitentiary at Bautzen until international outcry—led by “Amnesty” and supported by Bertrand Russell—secured his release.

It had all become too much for Brandt. The sort of man who become a Communist because he found joy in staying on his feet while everyone else kneeled was more fitted for the revolution than the Party. By 1953, this fairly senior Communist official was delighted to contemplate his own party’s “slide to disintegration.” His “third way,” however, is no more than a cloudy mixture of the early Marx, anti-nuclear pacifism, and a generalized concern for the rights of the individual; it is significant that this totally disillusioned man remained a Party member for another five years, crossing the border only when his arrest seemed probable.

There are plenty of Brandts still carrying out their Party duties in Eastern Europe today. Indignantly refusing to adapt their inner convictions, they are nonetheless dominated by the belief that “there is no salvation outside the Church.” Even Ludwik, who instantly paid for his defection with his life, only defied the Party when it was plain that his liquidation had already been decided.

His story, recounted by his widow, is a forbidding one. As the First World War drew to a close, six clever young men in a small Galician town pledged themselves to the revolution. All were consumed by it. Their very closeness as a group of friends prescribed their early success, their alienation from the Comintern under Stalin, and finally their doom. Ludwik, Fedia, Brun, Misha, Walter, and Willy became Communists, then agents of Soviet military intelligence and later of the NKVD, then victims of the purges. Two of their deaths became public knowledge in the West: the murder of Ludwik in 1937 became famous as “the case of Ignace Reiss” (a pseudonym invented for his funeral). Walter Krivitsky was found shot in a New York hotel, probably by his own hand, several years after he had defected and written his memoirs (ghost-written, Mrs. Poretsky emphasizes) under the title I Was Stalin’s Agent.

Our Own People is a good title. It has accuracy and irony. The group to which Ludwik belonged was an intimate one, owing much to its Polish origin. As Polish Communists of the first generation, its members had just that fatal combination of unique intimacy with the Soviet comrades and sovereign skepticism about their claim to infallibility which led—after most of the group were already dead—to Stalin’s dissolution of the party and massacre of its leaders. They also inherited from the tradition of Rosa Luxemburg a primary concern with the world revolution, and they scorned—though they served—Stalin’s doctrine of “socialism in one country.”

Advertisement

Elisabeth Poretsky, the survivor, is loyal to their memory. “Our own people” were intelligent, idealistic, cosmopolitan agents who formed their own networks in their own idiosyncratic way. “They” were usually Russians, the stolid and obedient men who carried out the really evil errands and who, in the next generation, were to become the sort of professional agent who betrays all his colleagues as a matter of course when he defects. (Books of “our own” reminiscences, like this one and Krivitsky’s, are more reticent than a first glance suggests: “we” do not simply blab our secrets to the other side.)

Ludwik operated in Berlin, Vienna, and Holland before returning to Moscow in 1929. There the six and their friends maintained a precarious and hungry existence, confiding to each other over suppers of bad herring and horse sausage their growing disillusion. Once their masters had seemed to be part of their intimate companionship in clandestinity, but now, as Fedia put it, “either the enemy will hang us or our own people will shoot us.”

In Paris, as the Spanish Civil War approached its end, Ludwik and Elisabeth helplessly encountered the stream of Soviet agents summoned back to Moscow at the height of the purges to what they knew would be their own destruction. Yet they went back, some to expiate crimes on their conscience, others because there was no other mental possibility but to obey. Elisabeth returned to Moscow for a few months to see the atmosphere for herself, and a memorable chapter describes “our own people” on the edge of the abyss: the interrogators studying their victims to prepare for their own imprisonment, the men waiting alone in hotel rooms, the telephones which silenced a gathering when they rang.

In the face of his own summons to Moscow, Ludwik decided to make the break. But for him, there would be no scuttle to the CIA, no gorilla-escorted flight to some guarded country house for interrogation and T-bone steaks. Ignace Poretsky, which was his real name, walked out into the open with a public letter to the Central Committee calling for a “fight without mercy” against the perverters of the revolution, and dedicating himself to the struggle to “free humanity of capitalism and the USSR of Stalinism.” Seven weeks later he was found shot dead near Lausanne, the gray hairs of the woman who had lured him into the trap still clutched in his fist.

Many years after the war, in America, his widow was to meet the man who had betrayed Ludwik to his executioners. There came to her in a darkened apartment the haunting figure of Marc Zborowski, the young “Etienne” who had been the beloved and trusted assistant of Trotsky’s son and the Fourth International in Paris. All along, he now confessed, he had been an NKVD agent. The deaths of “Ignace Reiss” and many others were clearly owing to his information. Zborowski had become an anthropologist, and his subsequent conviction for per-jury in an espionage case was denounced as “witch-hunting” and “human sacrifice” by a chorus of his colleagues at Harvard and Columbia. Art, as usual, had prompted life: The Groves of Academe, so transparently based on the Zborowski affair, had actually been written more than five years before it took place.

The life of Elisabeth Poretsky briefly intersected the life of Victor Serge, the veteran revolutionary who had served the cause in France, Spain, and the Soviet Union, and who had put his great talents as a writer at the service of the exiled opposition to Stalin. After Ludwik’s murder, she encountered him in the company of “Etienne” to whom the casual Serge showed letters and messages which may, in retrospect, have cost lives. Mrs. Poretsky, whose standards of security were naturally exacting, considers Serge to have been either a monster of indiscretion or, possibly, an agent himself. She finds it hard to swallow the accepted version that it was the protests of foreign intellectuals which got Serge out of prison and expelled from Russia in 1935, and hints at other explanations.

This seems an unnecessary suspicion. The man who wrote Memoirs of a Revolutionary and The Case of Comrade Tulayev was above all open, sometimes wildly so. His background was one of generous anarchism and of taking risks as magnificent as they were sometimes gratuitous. His opposition to Stalinism as a system was temperamental and total. Serge could not stand either mental or physical prisons: he had seen too much of them.

The latest of Serge’s books to be republished by Doubleday—a major public service, as they had been forgotten and had become unobtainable—is concerned with that early period of his life. Serge, a child of Russian revolutionary emigrants whose real name was Victor Lvovich Kibalchich, went to Paris in the years before 1914 and became associated with the anarchist bank robbers known as the “Tragic Bandits.” He was tried—unlike most of the others, he escaped the guillotine—and sent to a penitentiary for five years.

Outside it was wartime; inside, the men being slowly processed into mites could only regard war’s destructiveness as a message of vitality and hope. Serge, as an anarchist, was in any case inclined to regard the war as the world-ending cataclysm which would produce the Second Coming of revolution; and the reflection of a “mechanical” capitalist world in the routine of a model prison was already a familiar idea to him. These episodes and portraits from prison life convey in detail its methodical reduction of vivid human beings into gray shades too passive to masturbate.

Serge musters all his anger. And yet this is one of his least good books. It shocks, and no more. It may be that Serge actually found the memory of those awful years too painful to transform into art. Or, possibly, the cataract of history which separated the experience from the writing—he finished Men in Prison in 1929—diluted his own interest in the past and tempted him to force his own feelings. As he said at the time, he wrote this book out of “a heavy sense of duty.” It is Serge’s discharge of a debt, by reminding the world that when he walked out of that miserable labyrinth into the morning, other men remained behind—and remain there still.

[A note to publishers: the world is full of helpful Poles. There is no excuse for the barbarous practice of transliterating Polish names from Russian (Mrs. Poretsky) or garbling the most famous line of the most famous Polish poem (Heinz Brandt). This language and literature are worth getting right.]

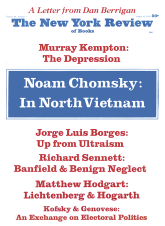

This Issue

August 13, 1970