Men hope to acquire certainty about the future and are always disappointed. The ancients consulted the oracle at Delphi and scrutinized the entrails of fowls. The Middle Ages relied devoutly on the relics of saints. When the Reformation opened the Bible to all, zealots fell upon the Prophetic Books, and the great Sir Isaac Newton spent more years conning the Book of Daniel than he did on discovering gravitation. Later a knowledge of history was expected to provide the answer. Increased understanding of the past would lead to increased understanding of the future. In practice historians guessed like other men and usually guessed wrongly. Most historians foretold success for their own country. Some preached woe. It was blind hooky in either case.

Now the historians have been superseded by the academic students of politics or, as they call themselves, the social scientists. Once more we are told that if only we accumulate enough facts the answer will come out like the winning combination on a fruit machine. An imponderable still defeats the best calculations. Human nature remains a mystery despite the efforts of the sociologists. For instance, Messrs. Mackenzie and Silver have written on British workingmen who vote Conservative.1 There are plenty of explanations after the event, but we are no nearer knowing why and when voters switch. Again, there is a splendid political atlas by Mr. Kinnear of every electoral result since 1885.2 The one thing missing is a series of maps on what men expected beforehand. Some would have been right. Some would have been wrong, which is not surprising.

Even the political pundits have been eclipsed by the pollsters. Before the recent British general election we had no less than seven different systems, each proclaiming the superiority of its method. Each came up with slightly varying results, but until the last moment they agreed on one thing: Labour was going to win. At the end one poll hesitatingly pointed to a Conservative victory, and now all the pollsters are claiming that they would have got the results right if they had counted still later. This is a sad conclusion. If these ingenious systems cannot get things right as little as a week or two days before, we are back at the old method of prophesying an event only when it has taken place. The wise expert is the one who remains silent while things are happening and then demonstrates that he had expected them to happen like this all along. We already have plenty of these. In fact nearly every commentator is busy explaining that he foresaw a Conservative victory and hesitated to say so. This is very good news for the historian who has always regarded this hocus-pocus of social science with contempt.

The public opinion polls certainly had an effect on the election results, though not in the way that was feared or foretold. It was widely conjectured that a large number of voters would go the way the polls were swinging, thus following the example of the Gadarene swine. This illustrates a basic, though incorrect, assumption of the social sciences. It is the Holier-than-Thou assumption. No social scientist assumes that he himself is moronic, materialist, hysterical. But he assumes it of everyone else. The masses or, it may be, the classes are the stock with which social sciences deal. The masses are imaginary and indeed nonexistent. I have never met anyone who answered “Yes” to the question: “Are you one of the masses?” The masses are always the other fellow, the man next door or across the street. In practice however it will be found that the so-called masses behave in much the same way as the social scientist or perhaps a little more intelligently.

So it was on this occasion. The voters did not take any notice what the polls were saying in one direction or the other. They did not vote in favor of the poll trend. They did not even vote, as I had hoped they would, deliberately against it. The public opinion polls were for the voters a complete irrelevance. Not so however for the Prime Minister James Harold Wilson. He was the victim of the polls, lured by them to disaster as often happens with those who consult an oracle. He had the social scientist’s contempt for the masses. He believed that they would swing as the polls told them to. He ordered a general election in the firm conviction that he had won beforehand. There was no need for a general election. The parliament elected in 1966 had still more than a year to run. There was no urgent crisis threatening the government except those engendered by its own follies. There was a large and docile Labour majority in the House of Commons.

Set against this was one sole factor and it was decisive: the polls were swinging Labour’s way. Harold Wilson hurried to get in on the act. Cynics asserted that he had rushed the general election in apprehension of the new economic crisis which may well blow up in the autumn. This is to credit Mr. Wilson with foresight, a gift he has not otherwise shown. Hitherto he has been a successful opportunist and inevitably succumbed to a favorable opportunity. There are few similar cases in British history. Of course governments have sprung general elections when they had something particularly telling to boast of or to sound the alarm about. But this was a matter of holding a general election solely in order to win it. Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield, is said to have been misled in the same way by a good run of by-elections early in 1880. If Mr. Wilson had studied history instead of the social sciences he might have remembered that Disraeli lost the general election of 1880.

Advertisement

The general election of 1970 was announced for No reason and was fought on No issues. The amount of No in the election was the only positive factor. Labour did not recite its achievements of the past six years, such as they were. It merely claimed to have undone the failures of the previous Conservative governments. If re-elected Labour would go on Not doing what the Conservatives had done. The Conservatives, and especially Edward Heath, their leader, were much praised—after the election—for being more constructive. They, it was said, had actually stated what they would do. Again not so in any significant sense. The Conservatives promised Not to go on doing what Labour had been doing. This promise is already producing some awkward consequences.

This remarkable negativism was not due to some immediate twist of circumstances or to the personal characteristics of the two leaders. It reflects rather a general doubt in Great Britain’s ability to take any initiative or pursue an independent policy. Most British politicians have lost faith in their country and in themselves. Conservatives do not believe in the Empire or Commonwealth. Labour men do not believe in Socialism. Instead of politics there are expedients, and these expedients wait upon events. This skepticism, of course, is created by the men of little faith, not by the situation. A nation can always find a policy if driven to it. Before the Second World War, for instance, we were told that Great Britain was no longer strong enough to lead others and must allow herself to be pushed along by events. In 1940 drifting was not enough. British statesmen and the British people resolved on a policy, ran a remarkably successful war, and achieved total victory over all their enemies. So it could be again.

We were told before the election that voters no longer swung from one side to the other. One pundit even discovered that people voted as their parents had done and that, as the younger generation now came predominantly from Labour parents, Labour would be in forever. This ingenious theory failed to explain why the parents had ever voted Labour in the first place, since all by definition ought to have voted either Labour or Conservative. When tested, the theory did not work. Voters actually made up their minds by a rational process instead of following the mass rules of social science. Of course there is a solid core of Labour voters, mostly working class, and a solid core of Conservative voters, mostly the conventional and respectable. But there are always those who do their own thinking.

It seems pretty clear that most electors, very sensibly, apply their minds to politics only when they have to. This maybe is why the public opinion polls were so erratic: they merely recorded how people thought they would vote before they had done any thinking. It has even been suggested—and this is a more attractive theory than most—that Labour lost the election because England was beaten in the World Cup. As long as England was in the competition, all television sets and most minds were tuned in to Mexico. But England was knocked out on a Sunday, and that left four days when there was nothing to watch or to think about except politics. Here again Harold Wilson was misled by the oracle which foretold an English victory.

In a contest of negatives, the Conservatives can usually win. After all this is what Conservatism is about—not to make changes unless they are absolutely necessary. Labour, despite its conservative elements, is by nature a reforming party, compounded of Radicals and Socialists. It cannot keep going without believing in something. Though there was certainly a real swing of voters from Labour to Conservative, there was also a considerable abstention by Labour voters and still more an indifference among Labour workers. The great disease of Labour leaders is to aspire to be a National government—very pleasing for themselves, but less inspiring for their followers. They rejoice to be the Queen’s ministers. They demonstrate, what is no doubt true, the sincerity of their patriotism. If National government is the aim, why bother to have a Labour and Socialist movement at all? Why not resurrect Ramsay MacDonald and have the National government of 1931 all over again? Harold Wilson took Stanley Baldwin for a model throughout his campaign—not a good example for a Radical leader to follow.

Advertisement

Real Radical leaders are far and few between, though they then make an impact which lasts for a generation. In this century we have only had Lloyd George and Aneurin Bevan, and I am not sure about Bevan. Venturing into American affairs, I would suppose that there has only been F. D. Roosevelt. Failing such figures, politics go jogging along, with the Radicals in spluttering, though not always successful, rebellion. The general election of 1970 was itself a sort of popular rebellion. The people had been treated with contempt, first by the pollsters and then by Harold Wilson. They responded by showing that the contempt was undeserved.

Apart from this, the election did not demonstrate anything in particular. It did not indicate a rise in racialist feeling. It did not show a profound dissatisfaction with economic conditions. The few candidates who espoused the Common Market were howled down, but maybe this too does not prove anything. In our equable climate, if you foretell that the weather tomorrow will be what it has been today, you will be more often right than wrong and also more right than the scientific weather forecasts. So it is likely to be in politics. They will be much what they have been, though perhaps a little less so.

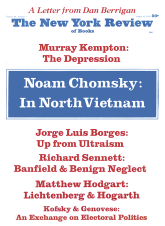

This Issue

August 13, 1970