Stanley Burnshaw’s long and closely knit book opens with the declaration that “poetry begins with the body and ends with the body.” Like the snake with its tail in its mouth, it closes with the same sentence, adding “it begins in one and ends in another.” In between a lot happens, or nothing happens: rather, a large number of fascinating questions connected with the poet-poem and poem-reader relationships are raised, discussed intelligently and cooly, and gently dropped back into that dark and unchartable sea from which they came. Or, to put it another way, in between there is a well-chosen anthology of what poets, critics, philosophers, and psychologists have had to say about the nature of art, how it comes about and what it does. Some of Mr. Burnshaw’s own contributions are worthy of the company they keep.

But as an argument? If it is an argument, it comes to no conclusion, or to so many conclusions as to amount to the same thing. To have come to a clear and single conclusion, Mr. Burnshaw would have had to limit himself severely or else to cheat, or of course to be simple. The variety of factors involved in the genesis of a literary work may not be infinite, but it is not far off. The variety of effects produced by a variety of poems on a variety of readers may not be infinite, but it is quite near. Compared with the exploration of art, the exploration of the moon is a weekend assignment for schoolboys.

The intellectually myopic are not so likely, I suppose, to be blinded with science. Which may be why I found Mr. Burnshaw’s physiological, biological, cerebral, and zoological excursuses less illuminating than they were meant to be. The use in artistic investigation of scientific procedure and parallels is nearly always a mistake, if a well-intentioned one: the outcome is a rather sorry thing by the standards of scientific discourse, so that all the champion of the arts can say, lamely, is that everything has been explained except what matters. It has to be added that Mr. Burnshaw’s concern is not with poetry as ersatz fodder for scientific methodology, but with poetry as an activity of the most complex and indeed most momentous kind, and his dealings with it are a good deal more delicate than those of Richards’s Principles of Literary Criticism.

A poem comes out of the poet’s total organism, psychophysical, mindbody, and goes into the reader’s total organism…. Mr. Burnshaw’s first chapter is rich in expert witness, yet for all its recondite detail, it tells us little we didn’t know before. It doesn’t tell us as much (or as vividly) as Lawrence does in his lively, casual-seeming piece, “Why the Novel Matters”:

Now I absolutely flatly deny that I am a soul, or a body, or a mind, or an intelligence, or a brain, or a nervous system, or a bunch of glands, or any of the rest of these bits of me. The whole is greater than the part. And therefore, I, who am a man alive, am greater than my soul, or spirit, or body, or mind, or consciousness, or anything else that is merely a part of me. I am a man, and alive, I am a man alive….

Among so much diversity of experience, some phenomena are recurrent: for example, the insistence by poets that they are being “used,” whether the force that uses them is called Inspiration or Unconsciousness, the White Goddess or the Dark Gods. You cannot write poetry just by wanting to, it comes or it doesn’t; and “coming” suggests a source outside the will, a “giver.”

But what about revision or re-vision, that which occurs in the course of what Mr. Burnshaw calls “reconstituted vision”? For unhappily not everything is always (or even often) given…. Does the poet agree with Frost that “if the sound is right the sense will take care of itself”? This proposition could as well be reversed, though perhaps no better reversed, since “sound” and “sense” are not simple and separate categories. Does the poet, along with Mallarmé, “yield the initiative to the words” and keep the obtrusive will in abeyance? Mr. Burnshaw points out very justly that “any such model of compliance omits the all-too-human in a writer.” The most “inspired,” the most unself-conscious writing is frequently the most embarrassingly self-ish. The will, sometimes after all a force for decency, collaborating with the analytical intellect, needs to obtrude: something must seek to moderate the whinings of the Unconscious, must open the poem to other people. Not infrequently the “given” is a present from Loving Us to Our Beloved Selves.

The conclusion Mr. Burnshaw reaches is that between the simple extremes of Involuntary and Voluntary there are an infinite number of gradations, of permutations and combinations. As so often in this book, we are left with a paradox whose contradictions all speak truth: the poet who said, “If poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all” is one whose work sheets are “a monument of ‘conscious artistry.”‘

Advertisement

It was Keats who defined “Negative Capability” as “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Though almost superhumanly free from irritability, Mr. Burnshaw is certainly reaching after fact and hoping to catch a few reasons. But he takes his failures with a good grace—he is a practitioner of poetry himself—as if he knows that most of what is catchable in this queer sea has been caught already and thrown back in to grow and prosper in its proper element. A sentence characteristic of him is this: “The foregoing sentences…are cumbersome, finical; but to write down even the comprehensive little that may surely be said of a poem and to convey its indispensable at-onceness would require a book-long sentence.”

In other connections (all of them connected, for Mr. Burnshaw’s subject is an organic whole) the situation is much the same: opposites are both right; without contraries there would be no progression; not either/or but a larger or smaller proportion of both or all three or four or five or… Thus, the coexistence of cultural diversity (and linguistic differences) with human sameness (and similarities in “language behavior”)… Thus, the apparent paradox inherent in “the pleasantness of the unpleasant in art”—of which Mr. Burnshaw makes rather heavy weather, as if, for once, he does suspect “pain” and “pleasure” of being true and unrelated opposites.

And then there is the problem of belief, whether the reader can and does suspend his disbelief and in his reading “go along with” views and doctrines from which he would ordinarily dissent. At times “belief” matters a lot, at others it doesn’t matter at all. Mr. Burnshaw cites an excellent instance; “A non-believer accepts the poem-prayer to the Sungod of Egypt but recoils from a Soviet Asia folkpoem which has changed the name of a traditional deity to ‘Lenin.”‘ I think we have to agree with him that if we read the Divine Comedy “purely as fictive art or insignificant fantasy,” then we are not reading the Divine Comedy…. Belief/disbelief is a part of our total organism which it would scarcely seem possible to deposit in a pigeonhole before we pass through the library turnstile!

But the more one thinks about it, the more exhaustingly complicated the problem seems. Why is it, for instance, that the present writer, a non-believer, can enter into the body of George Herbert’s poetry with what seems to him like reasonable ease and yet feels excluded from much of the Four Quartets? No doubt there are many answers in many specific cases, but there is no answer which is simultaneously utterable and applicable to sufficient poems and sufficient readers to amount to a “contribution to knowledge.”

A poem should not mean

But be,

said Archibald MacLeish, and Mr. Burnshaw adds, truly I believe, that if there isn’t something in the poem that makes “some acceptable type of sense” at once, then the reader will turn away without further ado. And so MacLeish can be inverted: “A poem before it can be for a reader must mean.” Mallarmé’s epigram that poems are made not with ideas but with words is equally reversible. The original saying was useful in its time, the inversion is more salutary today. Another witticism we would like to restructure is Gide’s “good sentiments make bad literature.”

These generalizations by poets and critics are half-truths or, rather, wholly true in certain circumstances, wholly untrue in others. Aperçus are like proverbs; they rely on the context for their truth and relevance. Sometimes “look before you leap” is a timely warning; at other times “he who hesitates is lost” is valuable advice. The only absolute answer to Mr. Burnshaw’s dilemmas is: “it all depends.”

Here and there one feels like adding one’s own reservations to Mr. Burnshaw’s. Elsewhere one finds oneself confirming him with anecdotes from one’s own experience. On the subject of “word music,” Mr. Burnshaw points out that “consonants and vowels do not exist as independent entities,” and the word is “sense-and-sonality.” This made me think of the eager student who claims in one essay that a succession of “s’s” creates “an atmosphere of soft, silken luxury,” and in the next that a succession of “s’s” creates “an atmosphere of sinisterness and serpentine malice.” Without sense, sonality is nothing—or, if we are to live up to Mr. Burnshaw’s standard of circumspection, next to nothing.

Advertisement

In discussing the occasional need for extraneous knowledge, especially biographical, in understanding a poem, Mr. Burnshaw remarks that without knowing that its author spoke as an active communist at a particular time, the reader of Brecht’s “An die Nachgeborenen” “could make only vague emotional sense of its confiding plea to posterity.” When an English translation of this poem was set recently as a practical criticism exercise for Singapore university students, one of them opined that it came from a released political detainee (perhaps the prearranged text of the TV recantation?) and another that it was written by one of those Students’ Unionists who are always finding fault with everything (a conservative citizen’s conception, maybe, of a potential detainee). A poet sometimes assumes that the personal circumstances in which a poem originated will somehow survive alongside the poem—but then, if they did, there would be little need for the editorial footnote or the teacher of literature. When one is already engaged by “some acceptable type of sense”—as I think is the case with this poem of Brecht’s—one is ready to investigate background or biography, one actively wants to. Our quarrel is with the poem which expects the reader to do the donkey-work in the absence of the dangling carrot.

Mr. Burnshaw invites expert attention, and perhaps readers more expert, more knowledgeable, might detect faults in the careful unfolding of his argument. One passage made me stop and doubt. He states that “not a single metaphor can be found in a great many excellent Chinese poems,” and he cites Waley’s translation of a piece by Emperor Wu-ti.* Chinese scholars deny that metaphor is less prominent in Chinese poetry than in Western verse, and some doubt whether Wu-ti is a sufficiently excellent poet for his practice to be adduced as an “excellent” example of anything Chinese. Mr. Burnshaw is talking about a particular translation, a modern one, and not about Wu-ti’s poem, and I suspect that if he had happened upon a Victorian translation, he would have found himself making a very different generalization about Chinese poetry! This lapse is the stranger in view of Mr. Burnshaw’s firm objection in a later chapter to “imitations” (“neither translations nor original poems but a species of improvisation”) and his caveat on the subject of translation: “I believe every verse translation should be accompanied…with a literal one in prose or a trot, for the protection of the reader and the author.”

Mr. Burnshaw is describing rather than prescribing, and descriptions, he points out, are not explanations. Such, as we have noted, is the nature of the subject. But this consideration doesn’t save the protracted urbanity of attitude, the scrupulously maintained judiciousness, from proving slightly fedious in the long run. Halfway through the long run I came across a passage in Ruth Pitter’s Preface to her recent Poems 1926-1966, which impressed me with its actuality, its sense of a human voice, a sense which Mr. Burnshaw’s more scientific prose is rather deficient in:

I think a real poem, however simple its immediate content, begins and ends in mystery. It begins in that secret movement of the poet’s being in response to the secret dynamism of life. It continues as a structure made of and evolved from and clothed in the legal tender and common currency of language; perhaps the simpler the better, so that the crowning wonder, if it comes, may emerge clear of hocus-pocus. (I think it is important to make the plain meaning of the words as clear as possible, but it cannot always be made entirely clear. Our only obscurities, I feel, should be those we are driven into; then a sort of blessing may descend, making such obscurity magical.)

Granted that obscurity and indefiniteness of meaning pose yet another complex problem, one might still like someone to get up and ask that poems should customarily stand on their own feet—I am not now thinking of the biographical difficulty in Brecht’s poem, for instance—to ask that the poet should do the work, his fair share of it, and not leave it to the researching reader to seek clues on other ground. As Miss Pitter suggests, our only obscurities should be those we are driven into. It is all very well for the Japanese to practice “indefiniteness” in their conventional forms, since the reader knows what the indefiniteness conventionally signifies. It is less well when contemporary practitioners in the West seek sanctimonious refuge in dot-dot-dot from their own lack of significance. The poet should be a maker, not a source of fragments for someone else to stick together.

The Seamless Web probably does as much as it could possibly do, given its spinner’s exquisite manners. What leaves me rather disconcerted is that the reading of it took me longer and required a considerably greater effort of will than the reading of any of Dickens’s longer novels or a sizable portion of Paradise Lost. For this looks like another paradox…. Art is already long—should talk about art, however intelligent, be longer?

At all events, Mr. Burnshaw’s readers will want to associate themselves with his estimate of the continuing importance of art for mankind. In his closing remarks on the conflict in the mind between “diencephalon” and “cerebral cortex,” or between primal forces and civilized forces, he proposes that one truce between them is art, when “certain innermost needs of the organism fulfill themselves through imaginative creations.” The mystery—of the needs and how they are fulfilled—remains. Perhaps it is meant to.

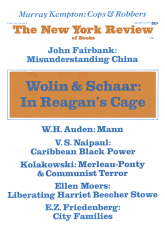

This Issue

September 3, 1970

-

*

A solecism, since ti signifies “Emperor”; therefore either “Wu-ti” or “Emperor Wu.”

↩