I

The familiar materials of popular discontent, quietly persisting through three decades of “affluence,” seem once again to be rising to the surface of American political life. Distrust of officials and official pronouncements; cynicism about the good faith of those in positions of great power; resentment of the rich; a conviction that most things in life are “fixed”—these attitudes were there all along, of course, forming part of the folk wisdom of the American working class, but they attracted little attention so long as it was possible to believe that the worker had become middle-class in his tastes and outlook. Now that they seem to be taking political form, the illusion is harder to maintain.

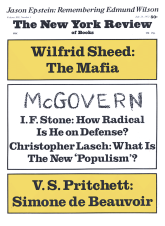

A grass-roots rebellion against the Democratic Party establishment gives rise to the McGovern and Wallace candidacies, antagonistic movements that nevertheless have in common that both are hated and feared by the official leaders of the party and flourish in the face of official attempts to suppress them. In Illinois the Daley machine suffers a sharp setback. In Lordstown, Ohio, GM workers are raising not the traditional issues of bread-and-butter unionism but a more disturbing question: Why does work have to be organized in such a way as to make it boring and meaningless? Studies show—what we hardly needed studies to find out—that most Americans are bored with their jobs. A Harris poll reveals the equally unsurprising information that our political institutions are distrusted by a majority of the people.

Distrust and boredom are two sides of the same mood; both flow from the experience of being without power. Having no control over his work, over governmental policy, over the press and television, or over the education of his children, the citizen feels himself manipulated to suit the interests of the rich and powerful. Busing—its unreality decried by established political spokesmen—has become an important issue in American politics because it represents for many people the most palpable threat of outside interference with their lives: the sacrifice of defenseless children to a bureaucratic design imposed from above. (That the children themselves seem not to mind is perhaps beside the point.)

In the new political climate—the existence of which the Democratic primaries, more than anything else, have made known—people are rediscovering “populism.” In the Fifties scholars ridiculed populism as a backward-looking agrarian fantasy. Some saw in the populism of the 1890s the seeds of American “fascism.” Others interpreted it as “paranoid,” anti-intellectual, and obsessed with issues of merely symbolic importance—the progenitor of McCarthyism and other right-wing movements “against modernity.” In the late Fifties and early Sixties a number of historians began to challenge these interpretations, arguing that the populists were neither nativist nor anti-Semitic, reminding us that populism was a genuinely radical movement with a radical program.1 In some cases they asserted an identity—spurious, in my view—of populism with socialism.

This new scholarship has had the effect of making populism intellectually respectable again. Joseph Kraft, in a review of the Newfield-Greenfield “manifesto,” expresses the older view of populism when he worries that a revolt against economic injustice, of the kind Newfield and Greenfield are trying to encourage, would degenerate into a demagogic crusade in which “the malign side of populism” would once again assert itself—“the side that in the past has fostered isolationism, anti-intellectualism, hostility to Jews and Catholics, and what Richard Hofstadter called the ‘paranoid style’ of American politics.” But it is precisely the association of isolationism, anti-intellectualism, anti-Semitism, and political paranoia with populism that can no longer be taken for granted. The revival of populism as a subject of general concern, while it derives in the first place from recent political events, also derives from—or at least was facilitated by—the scholarly rehabilitation of populism.

According to the interpretation that prevailed in the Fifties, populism was a rear-guard movement, rooted in the status anxieties of a declining class, the petty bourgeoisie; and although it would doubtless continue to manifest itself in such reactionary forms as Goldwaterism and the John Birch Society, it could hardly be regarded as the wave of the future. The recent reinterpretation of populism, by stressing its radicalism, has made it contemporary again—for many people, indeed, has made it a more appropriate answer to the crisis in American society than the radicalism of the Sixties.

A new populism might be expected to appeal not only to those directly victimized by economic injustice but to students and intellectuals who are tired of the ideological wrangles of the left and seek relief in a broadly based reform coalition in which theoretical niceties are subordinated to practical results. The populist revival reflects more than the growing impatience of the “average American”; it also reflects the disillusionment of many leftists and ex-leftists. Clearly the new populism is one of several candidates hoping to inherit what remains of the new left, others being women’s liberation, the “counter-culture,” and some form of socialism.

Advertisement

It may be suggestive of a new mood on the left that Newfield and Greenfield barely mention the new left; they simply by-pass it. In their eagerness “to return to American politics the economic passions jettisoned a generation ago,” they seem to assume that nothing at all can be learned from the radicalism of the Sixties. They pass over that complex experience with a brief criticism of the youth culture (actually of Charles Reich), a few snide references to “middle-class radicals,” and the observation—which hardly disposes of the subject—that “the New Left in its Weatherman, Panther, and Yippie incarnations has become anti-democratic, terroristic, dogmatic, stoned on rhetoric, and badly disconnected from everyday reality.”

They say nothing about the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, or the new left attack on the multiversity. By their own admission their program does not address itself to “the legitimate grievances of blacks, or the women’s movement,” or to “civil liberties, disarmament, and ecology.” Their populism speaks to “concrete economic interests.” In appealing frankly to “self-interest” as the motive force of politics, it is unashamedly liberal, while at the same time seeking to dissociate itself from the “elitist” and manipulative liberalism of Adlai Stevenson, Eugene McCarthy, and the Ivy League technocrats in the Defense Department. The populist program is “designed to move us closer toward justice, not Shangri-La.”

Newfield and Greenfield propose a variety of economic reforms. They would attack the concentration of wealth and economic power by means of antitrust suits, federal regulation of corporations, and tax reform. (In tax reform, their suggestions resemble the unamended McGovern proposals, combining higher rates for the rich with exemption for the poor and closing various loopholes.) Newfield and Greenfield would bring banking and insurance companies under control by means of public representation on boards of directors. Similarly they see union participation in management as a means of bringing corporations to public accountability. (This of course is not the same thing as worker control.) They demand public ownership of utilities (so did the populists in 1892), land reform designed to break up concentrations of land ownership and to thwart real estate developers, and reform of communications to prevent monopoly and encourage diversity.

Rightly convinced that “law and order” is a real issue for working people and not simply a slogan of right-wing demagogues, they advocate gun control, and end to police corruption and bureaucracy, penal reform that would emphasize rehabilitation instead of custody (another good nineteenth-century proposal), and, somewhat ominously, an end to “police practices that hinder the work of deterrence”—measures, it must be said, that hardly go to the heart of the problem. They propose a program of national health insurance, closer supervision of the drug industry, and a restructuring of the medical profession to allow “paraprofessionals” to play a larger role (but without noting the implications of this last suggestion for professional training in general). In short, they favor an “attack on economic privilege” all along the line.

The first thing to be said about this program is that it is too modest even within its own limits. There is no reason for populists to ignore such important issues as housing, transportation, and education, as Newfield and Greenfield do, or to pass so lightly over questions of foreign policy. Instead of examining the connection between American foreign policy and the concentration of wealth, Newfield and Greenfield subscribe to the questionable thesis that what is wrong with foreign policy can be attributed to the influence of intellectuals committed to “the mode of technocratic thinking and operating.” They treat racism purely as an economic matter: the concentration of economic power “leaves whites and blacks competing over too scarce public resources.” They by-pass the complicated issue of school desegregation, probably because it does not readily yield to an economic interpretation.

Again and again the authors try to avoid the troubling questions of the Fifties and Sixties by reviving issues that were central to American politics before these new issues arose; yet in many cases the roots of these issues must be traced directly to the “populist” administrations of Roosevelt and Truman. Newfield and Greenfield hark back nostalgically to Harry Truman’s “give-’em-hell” campaign of 1948—“one of the last examples of a successful populist coalition”—but forget that it was Truman who formulated the containment policy and made the first American commitments to Vietnam.

Some of the omissions and evasions of the Populist Manifesto are peculiar to the Newfield-Greenfield version of populism, and it is accordingly possible to imagine a slightly more rigorous statement of the case; but most of these evasions are intrinsic to populism itself. Certainly populism has never been “anti-imperialist in foreign policy,” as Newfield and Greenfield claim. In The Roots of the Modern American Empire, William Appleman Williams showed that American farmers saw an expansionist foreign policy as enlarging their markets; nor did the populist leaders quarrel with this assessment. There is admittedly a tradition in populism that sees war as a conspiracy of international bankers and munitions-makers, but this tradition is compatible with nationalist and even jingoist views and hardly provides a solid basis on which to oppose American expansionism—though it might be of some use at the moment in extricating ourselves from Vietnam.

Advertisement

Nor is populism reliably antitechnocratic, as Newfield and Greenfield also maintain. In its more sophisticated forms—as in the sociology of Lester Frank Ward and Thorstein Veblen—it advanced a technological interpretation of social “evolution” according to which the new technological and scientific elite were functionally indispensable to advanced industrial society, and thus assured of a commanding position in it.

Finally, populism, because it treats politics as a reflection of economic self-interest, has always found it difficult to explain the connections between politics and culture. Newfield and Greenfield with good reason believe that culture should not be confused with or substituted for politics (as in the theories of the counter-culturists); but this does not mean that the connections between them can be safely ignored. To make these connections, however, requires a theory of class and an understanding of the way in which class interests, seldom presenting themselves directly in economic form, are mediated by culture, which in turn acquires a life independent of its social origin. Racism, for example, though it once furnished a rationale for slavery and other forms of exploitation, no longer has a clear basis in economic self-interest; nevertheless it survives as a powerful force in American society and cannot be eliminated simply by a more equitable distribution of goods.

Eliminating racism demands, at the very least, an equalization of educational opportunity; but here again a merely quantitative approach to the problem—more spending on schools, an attack on “privilege”—cannot deal adequately even with its economic complexities (such as the relation between school taxes, segregated suburbs, and disintegrating cities), let alone with the cultural questions to which discussions of education are likely to lead: Is compulsory schooling inherently biased in favor of existing class structures? Is there some relation between the schools’ monopoly of education and the declining educational content of work—and for that matter of leisure?

II

The narrowness of populism appears immediately if we turn from the Populist Manifesto to Michael Harrington’s elaborate restatement of the socialist position—more properly, of the social democratic tradition, which it is one of his purposes to rescue from the scorn of the new left. Since socialism is simultaneously a theory, a body of practice with a long and complex history, and an ideal, Harrington has to deal with a vast range of material, including much that cannot even be touched on in this review. Essential to his undertaking are a reinterpretation of Marx; a historical analysis of “socialism” in practice in the USSR, China, and the “Third World”; an analysis of the social democratic tradition in Western Europe; and an account of “the American exception.” These will be considered here in that order, although the book weaves them together in a manner sometimes illuminating and sometimes confusing.

Harrington’s version of Marxian theory owes much to the recent work of George Lichtheim, Shlomo Avineri, and David McClellan. It restores Marx’s early writings to a position of central importance while denying a radical break between the young and the mature Marx. It stresses the philosophical origins of Marx’s thought and insists that Marxism forms a unified whole that cannot be broken down into Marxian economics, Marxian sociology, and other fragments. It treats as crucial to the meaning of Marxism Marx’s controversies with Jacobinism on the one hand and with Lassalle’s state socialism on the other.

What caused Marx to reject both these positions, according to Harrington, is that both ignored the social, economic, and cultural preconditions that Marx regarded as absolutely indispensable for the creation of a socialist order. The Jacobin tradition, surviving in the conspiratorial movements led by Blanqui and Bakunin, hoped to realize socialism through an act of revolutionary will and the heroic sacrifices of a revolutionary elite basing itself on the outcasts and dregs of society—Bakunin’s “proletariat in rags.” Lassalle, on the other hand, wanted to ally the emerging industrial proletariat in Germany with the reactionary anti-capitalism of the landed nobility. His tactics helped to prepare the way for Bismarck’s revolution from above.

Marx, however, insisted that socialism had to rest on economic abundance, on modern technology and modern culture generally, and on relations of production already “socialized” by capitalism. He argued that by demanding cooperative labor on an unprecedented scale capitalism had brought the workers out of their isolation and thus created conditions in which for the first time it was possible for them to think of themselves, in Harrington’s words, as “cooperators in the gigantic enterprise of satisfying human needs.” The “socialization” of labor made possible productivity on an unheard-of scale; but bourgeois society, according to Marx, by imprisoning this technology in a system of private commodity production, prepared the way for its own destruction and its succession either by a new form of barbarism or by socialism. This “contradiction” is Marx’s central theme, Harrington properly insists; and it “is more relevant today than when he wrote Das Kapital.”

If this makes Marx sound a little like a Menshevik, insisting that it is impossible to skip historical stages on the way to socialism, the confusion may lie in the very notion of “stages.” Drawing again on Lichtheim—and also perhaps, though without acknowledgment, on Eric Hobsbawm’s introduction to Marx’s Pre-Capitalist Economic Formations, where this question is also discussed—Harrington makes it clear that Marx, after flirting with a crude theory of historical stages in the Communist Manifesto, treated the development of capitalism out of feudalism in Europe as a unique and unprecedented event, not likely to recur elsewhere in the world. He saw no inevitable progression from slavery to feudalism to capitalism. Those who proceeded to read this meaning into Marx’s analysis of primitive accumulation in the West transformed, according to Marx himself, a specific historical discussion into a “historico-philosophic theory of the general path every people is fated to tread, whatever the historic circumstances in which it finds itself.”

The rise of a socialist movement in Russia, near the end of Marx’s life, raised this issue in a way that showed the intersection of practice with theory. Far from arguing, as the Mensheviks were later to argue, that Russia’s backwardness condemned her to repeat the “stages” of historical development in the West, passing first through a bourgeois revolution and thence to socialism, Marx and Engels came to believe, as they put it in 1882, that a revolution in Russia might “give the signal to a proletarian revolution in the West”—just as Lenin believed it would in 1917.

This does not mean that they endorsed the theories of Bakunin, Herzen, and the Russian populists that peasant communes in Russia could in themselves form the basis of a socialist society. Indeed the more closely they considered the “Asiatic mode of production,” the more they came to identify the lack of private ownership in land with the rural stagnation prevailing in large parts of the globe. Bakunin’s ideas, according to Marx, were “schoolboy’s asininity! A radical social revolution is bound up with historic conditions; the latter are its preconditions. It is thus only possible where there is capitalist production and the proletariat has at least an important role.”

There remained the possibility, however, that a socialist revolution in Europe, whether touched off by a Russian revolution or by some other crisis, would itself contribute materially and culturally to Russia’s economic development. Rather than positing a naïve theory of historical “evolution,” Marx recognized that events in one part of the world influence events in other parts, and that the outcome of developments in a country like Russia (and to an even greater degree in countries under Western colonialism) to a considerable extent depended on developments in the more advanced countries. Not that the Russians lacked the moral autonomy or the capacity to make a revolution; but if it was true that socialism demanded certain pre-conditions to be found only in the West, the form that a Russian revolution would take depended on European events.

It is well known that Lenin, whatever his other departures from Marxism, also believed that the success of the Bolshevik revolution depended on a socialist revolution in Europe. When this revolution failed to take place—or rather, when the social democrats joined with the bourgeoisie in putting it down, at least in Germany—Lenin was faced with the difficult task of explaining how the Bolsheviks could claim to be leading the socialist reconstruction of a country still on the verge of capitalism. In particular he had to justify the Bolshevik party dictatorship in the face of the condemnation by Marx and Engels of elitist and conspiratorial tactics. “In the process,” Harrington observes, “he laid the ideological basis for a totalitarian regime which, I suspect, he would have abominated.”

Confessing that “in effect we took over the old machinery of state from the Tsar and the bourgeoisie,” and that the Russian workers “have not yet developed the culture required” to build a more democratic political structure, Lenin nevertheless tried to convince himself that educational work among the peasants—a “cultural revolution,” in his phrase—“would now suffice to make our country a completely socialist country.” In an even greater departure from Marxism, he also insisted that the problems of Russian backwardness could somehow be solved by joining Russia to countries even more backward, since “in the last analysis, the outcome of the struggle will be determined by the fact that Russia, India, China, etc., account for the overwhelming majority of the population of the globe.”

Whatever ideological gloss Lenin might choose to put on the situation, the fact remained that in the absence of a European revolution, the “socialist” state in Russia would have to perform the role of the bourgeoisie, and moreover that it would have to carry out the work of primitive accumulation under extraordinarily unfavorable conditions, in a world still dominated by Western imperialism. Under these circumstances, as Marx had foreseen, socialism amounted to no more than the collectivization of poverty.

More recent experiments with “socialism” in countries even more backward than Russia in 1917, according to Harrington, have only confirmed the wisdom of Marx’s original insight. The attempt to impose socialism on such countries as China, Cuba, and North Vietnam has led to one or another variety of “bureaucratic collectivism” (a concept Harrington derives from Max Schachtman) or else, in countries like Egypt, to a “socialism of the barracks” in which the military regimentation of an agricultural population is justified in the name of an ideal with which it has nothing in common.

Harrington’s argument, it will be seen, hardly commends itself to Western radicals who look for deliverance to an uprising of the “Third World”; nor will it commend itself to latter-day Leninists or followers of Mao, Che, and Frantz Fanon. Nevertheless a great many Americans who call themselves socialists will find little to disagree with in the argument up to this point. More dubious is Harrington’s analysis of developments in the advanced countries. A detached view of the matter would seem to require recognition that social democracy in Europe has become as much a dead end as Leninism and its offshoots in Russia and the non-Western world.

Not that a “balanced view” demands that both branches of the socialist tradition receive equal criticism. But if we exaggerate the accomplishments of European social democracy, we shall find it difficult to explain among other things the persistence of capitalism and imperialism. At the very least it would seem important not to begin with a prejudice in favor of social democracy. To say, for example, that the failure of the proletarian revolution in Europe—the same event that had such disastrous consequences in Russia and other undeveloped countries—left the Western socialists in a cruel dilemma, cast both as “doctors” and as prospective “heirs” of an ailing system, is true but inadequate. In order to complete the observation, we need to note the socialists’ own contribution to the failure of that revolution. Harrington sees that the First World War was a turning point for European socialism, but it seems to me that he minimizes the lasting damage it inflicted on the movement.

In an early chapter he makes the important point that “the very growth of the socialist movement [in prewar Western Europe] was, in some measure, a result of working class optimism in a society in which the masses were making some real gains.” Responsible to a growing constituency, organized increasingly along the lines of the bourgeois parties, and increasingly enmeshed in bourgeois political institutions, the social democratic parties were “utterly unprepared to take to the streets” when “World War I broke out and revolutionary tactics against the government itself were required if the antiwar promises were to be redeemed.”

But it is necessary at once to add that the socialist movement never recovered from this debacle. Without invoking as an explanation of its behavior the theory that its constituency, the working class of Western Europe, is in reality a privileged sector of the world proletariat—a theory Harrington rightly rejects on the grounds that it stretches the term “proletariat” beyond recognition and ignores important differences within the Third World “proletariat” itself—we should still have to admit that the social democratic movement has pretty consistently supported imperialist wars ever since 1914. In particular it has enthusiastically endorsed, at least until recently, the international crusade against communism. It is this dismal record that makes it “problematic,” to use one of Harrington’s favorite words, whether social democracy any longer represents the hope of those who long for fundamental changes in our social and political life, and for whom the most important evidence of the need for change lies in the reckless, destructive, militaristic, and inhuman policies of the Western powers, especially the United States.

Social democracy has a bad record in domestic affairs as well—and this part of its history is clearly understood by Harrington, though he seems reluctant to draw the proper conclusions. Because they clung doggedly to an outmoded program of nationalizing industries, European social democrats, whenever they were in power, much too readily accepted responsibility for taking over decrepit industries, while the healthy ones remained in private hands. Thus in Western Europe nationalization had served to “socialize the losses of capitalist incompetence,” in Harrington’s excellent phrase, while at the same time acting “as a subsidy to the private sector.” Harrington shows that the social democratic parties have adopted as their own the cult of economic growth; he shows that they are increasingly attracted to managerial and technocratic solutions; in short he shows that they have gradually become exponents of a kind of “socialist capitalism.” Yet his only criticism of the 1959 Godesberg program of the German Social Democratic Party, which marked the complete triumph of these tendencies in European social democracy, is that its revisions of the orthodox program, while “overdue,” “went too far.”

Among other things, the Godesberg program announced that “the Social Democratic Party has ceased to be a party of the working class and has become a party of the people.” This was one of the changes, according to Harrington, that was “overdue,” since Marx himself, “once he got over the simplifications of the Communist Manifesto,…never believed that society was polarizing into two, and only two, classes, and every serious socialist tactician who came after him was aware of the need to reach out beyond the proletariat.” But Harrington’s argument is disingenuous. The question is not whether it is necessary to “reach out beyond the proletariat”—something nobody in his right mind would deny—but whether history (or at any rate modern history) is conceived as a struggle between classes or merely between “the people” and their oppressors. If the latter, then populism is fully as appropriate a position as socialism; surely Americans do not need Marx to instruct them in the rights of “the people.”

It is not easy to see in what sense a party identifying itself as the “party of the people” can be said to be a Marxist party at all. Harrington concedes that the Godesberg program—which also abandoned public ownership as a panacea, not in favor of something more radical, however, but in favor of various welfare programs—does “not go beyond American liberalism.” But here again his chief criticism—that the German Social Democrats were “much too optimistic about capitalism”—seems to miss the point, namely that they had nothing to put in its place. They were too optimistic, Harrington goes on to explain, because they ignored the persistence of poverty; but poverty too is something we did not need Marxism to discover or to account for. The authors of the Populist Manifesto comment again and again on the persistence of poverty, citing Harrington’s own book, The Other America, as an authority; but they certainly do not draw the conclusion that poverty is a function of bourgeois class rule or that socialism is the only possible solution.

Reading Harrington’s account of European social democracy leaves one in some confusion. On the one hand it appears that the social democrats have failed as an opposition and have in fact become indistinguishable from welfare liberals. On the other hand it is not clear what Harrington thinks they should have been doing instead. It is certainly not my own view that they should have been engaging in revolutionary terrorism. A popular movement has a responsibility to its constituency (although one of these responsibilities is to educate it, instead of merely reflecting its narrowest prejudices) and cannot afford the luxury of intransigent noncooperation in the everyday affairs of the state. The price of having a constituency at all is that one has to look out for its immediate interests. But it does not necessarily follow that a socialist party should content itself, in the words of the Godesberg platform, with “a step by step change in social structure.” Such a policy goes beyond recognizing the need for immediate reforms; it implies a piecemeal theory of social change, according to which socialism will somehow emerge as the sum-total of liberal reforms.

Not all European socialists, of course, have subscribed to this theory. Some of them in fact have tried to work out a version of socialism that avoids the dangers of Leninism and social democracy alike; and one of the puzzling things about Harrington’s book is that these socialists—the most interesting in Europe since the First World War—are completely ignored. Why does his book contain only isolated references to Rosa Luxemburg and Gramsci, and no reference at all to that important movement in European Marxism led by Lukács, Korsch, and the Frankfurt school? Why, for that matter, is there no discussion of the philosophical crisis of Marxism—the growing tendency toward positivism in both Leninism and social democracy—from which these theorists were trying to rescue Marxian thought?

Harrington’s account of Marxism is itself indebted to this theoretical movement, which was responsible for rediscovering the early Marx and for re-emphasizing his Hegelian origins. Nevertheless Harrington’s long and seemingly exhaustive study of socialism ignores it, perhaps because this particular re-interpretation of Marx was aimed as much against social democracy as against “bureaucratic collectivism.” But precisely because it tried to restore to European socialism a revolutionary perspective, the absence of which Harrington occasionally seems to deplore, it would seem to deserve some consideration, if only in order to help us to understand why it failed to have any practical consequences.

III

If Harrington’s analysis of socialism in Western Europe is unsatisfactory, his treatment of the United States is even worse. He requires us to believe that the United States had for years harbored a vital and growing social democratic tradition, an “invisible mass movement,” and that we have been unable to recognize it, not because it doesn’t exist, but because our eyes are blinded by European models and precedents. This “invisible mass movement” is, of course, the American labor movement, which has built a “political apparatus” that constitutes “a party in all but name.”

Whereas the usual interpretation of American labor history sees the defeat of socialism in the AFL in the 1890s as a decisive event marking the complete capitulation of the AFL to a policy of business unionism, Harrington argues that this defeat was only temporary and that in effect “the AFL reversed its 1894 decision over the next thirty years.” Without admitting as much, the AFL abandoned its opposition to political action when it joined the Conference on Progressive Political Action in 1922 and backed LaFollette in 1924. The organization of the CIO in the Thirties, together with the formation of Labor’s Non-Partisan League, Harrington believes, completed the reorientation of the American labor movement and gave to the New Deal, in which the unions allegedly played an important role, a “social democratic tinge”—in words Harrington quotes from Richard Hofstadter.

Recent leftist historians, according to Harrington, ignore the underlying radicalism of the New Deal only because they are blinded by the rabid antiliberalism of the Sixties. (How then do we account for the fact that Hofstadter himself came to a similar conclusion about the New Deal in 1948; he found it essentially opportunistic, patching up the structure here and there while leaving the underlying problems unsolved.)

That the labor movement could have transformed itself into a social democratic movement without adopting a socialist ideology does not greatly trouble Harrington; for it had long since been apparent to Marx himself, as he wrote in 1846, that “communist tendencies in America” might originally take “seemingly anti-communist, agrarian form.” Admitting that Marx and Engels “clearly expected that in the not-too-long run the exigencies of capitalist production would bring forth a socialist movement in the United States just as in Europe,” Harrington nevertheless leaps from Marx’s comments on American agrarianism to the much more general and dubious conclusion that socialism first appeared in America “in a capitalist guise” and that, indeed, this “dialectical irony” (!) is “still in force over a hundred years later.”

One can only wish that the “guise” were not so impenetrable. Is it merely a willful blindness that prevents us from seeing a socialist in George Meany, whose vaporings about securing “for the great mass of the people…a better share of whatever wealth the economy produces” are quoted by Harrington to show that his “definition of socialism…more or less coincides with that of the revisionist social democrats” in Europe? Not only is Meany a socialist in disguise, according to Harrington, but the heavy union support for Humphrey in 1968 shows that “labor had clearly made an ongoing, class-based political commitment and constituted a tendency—a labor party of sorts—within the Democratic Party.”

But the unions, during all this time, were among the stanchest supporters of American foreign policy. Harrington passes over the cold war in silence and refers to Vietnam only to suggest that this unfortunate incident provoked an “estrangement” between the labor movement and middle-class radicals and prevented “academics and journalists” from seeing “the profound change in labor’s social programs and political organization”—a “change,” it appears, that was demonstrated by its ardent support of Humphrey in 1968!

My skepticism about Harrington’s “invisible social democracy” does not rest on the belief that the American working class is hopelessly reactionary and has to be written off as a force for change. Nor do I deny that a radical tradition runs through the history of the working-class movement, a tradition that has been ignored by historians who identify radicalism too narrowly with the formation of socialist and labor parties, and conclude that the American working class has therefore been bourgeois from the beginning. Stripped of the conclusions to which Harrington pushes it, much is valuable in his interpretation of working-class history. For example, he comes down heavily on the cliché that a relatively high standard of living has made the American worker conservative. On the contrary, Harrington argues, “The egalitarian ideology and the lack of clearly defined limits to social mobility made for greater individual discontent among the workers.”

Nevertheless when we consider the collapse of working-class radicalism after the Second World War, the purge of communists from the CIO, the unions’ unremitting anticommunism and support of the cold war, their support for defense spending, and their indifference to ecological issues or questions of worker control, we must wonder what has become of earlier traditions of labor radicalism. Would it be too much to say that their revival depends, among other things, on the overthrow of the present leadership of the labor movement? Harrington refuses to consider this possibility. He has convinced himself that the union movement in its present form already amounts to a secret social democracy. Is this why it supports Humphrey against McGovern? I disagree with Harrington’s belief that the most effective way for American socialists to act is by affiliating themselves with the left wing of the Democratic party; but even if this were an effective strategy, we would still have to know where it leaves the labor unions, which are in the center of the Democratic Party, and on some issues on its right.

Harrington’s impressive scholarship, his exposition of Marx, his lucid discussion of Leninism and the false socialism of the Third World, his astute observations about the failure of social democracy in Western Europe are enlisted in support of a program for the United States that in many ways resembles the populism advocated by Newfield and Greenfield. To be sure, Harrington understands the difference—in theory—between socialist planning and neocapitalist planning. He recognizes the limits of liberalism; he sees the broader implications of such issues as housing and transportation (as Newfield and Greenfield do not). In the end, however, he advises us to work through the unions and the Democratic Party—and this at a time when large numbers of people are finally beginning to question the historic inevitability of those institutions.

In one respect the Newfield-Greenfield variety of populism actually seems preferable to Harrington’s socialism, since it is conceived explicitly as “a movement,” not as “a faction yoked to one political party or one charismatic personality.” It has the additional advantage of being unencumbered with an ideology most Americans associate with despotism. If “socialism” is to issue merely in liberal reforms, why should their success be jeopardized by associating them with socialism?

Once again I hope it is clear that I do not see the alternative as a policy of ultraleftism. Like Harrington, I believe that revolution is unlikely and that the left should abandon its revolutionary pretensions and follow a policy of “strategic reforms.” But Harrington denatures this concept—which he borrows from André Gorz—by identifying it with traditional social democratic tactics, whereas structural reform is “by definition,” according to Gorz, “a reform implemented or controlled by those who demand it” and is intended as an alternative not only to Leninism but to social democracy as well. Structural reform is incompatible with the present policies of the trade union movement. It is also incompatible with the kind of planning that seeks merely to “reorder priorities.”

To say with Harrington that “the people rather than the corporations with Government subsidies should decide priorities” is too abstract; what this means concretely, as Gorz points out, is that the struggle to reduce military budgets—to take an example made timely by the McGovern campaign—“will remain mere agitation and abstract propaganda so long as the labor movement has not worked out, factory by factory, industry by industry, and on the level of national planning, a program of reconversion and reorientation of the armament industries.” Lacking such a program the left, even if it finds itself in power, will be “torn between the political desire to abandon the program [of military spending] and the pressure from the unions at the factory level for whom the existing program has come to mean the defense of their employment.”2

The recent campaign in California provides a vivid illustration of this conflict, in which Humphrey was able to identify himself precisely with the unions’ defense of their jobs. What is heartening about the California election and about the primaries in general is that these tactics did not prevent McGovern from attracting working-class support (though not so much the support of workers directly dependent on military spending, like the aerospace workers of California). McGovern’s success may mean that many workers no longer regard the labor leadership as altogether representative of their political interests. Instead of trying to persuade themselves that the union bosses are socialist in all but name, socialists should welcome this disaffection and do everything possible to encourage it.

IV

Lest the astonishing rise of George McGovern be taken as a demonstration of the wisdom of social democratic strategies and of the possibility that socialists might be able to constitute themselves as the left wing of the Democratic Party, it is necessary to remind ourselves that McGovern’s election would hardly mark the beginning of a peaceful transition to democratic collectivism. The importance of McGovern lies in the fact that he has succeeded, in spite of the combined opposition of the party chiefs and the labor bureaucrats, by appealing directly to the belief of many people that their officially constituted representatives are no longer responsive to their needs. More than the issue of tax reform, more even than his unyielding opposition to the war, the issue of “credibility” has worked in McGovern’s favor. His only hope of election—assuming the nomination is not stolen from him at the last minute (in which case the party would be wrecked beyond hope of repair)—is to continue to exploit this issue and to identify himself with a growing revolt against the political establishment.

The course of the campaign indicates that McGovern could not have hoped to win either the nomination or the election in the ordinary way. Events since California have made this doubly clear. After McGovern’s victory there, normal political decencies demanded that Muskie endorse McGovern and that the party close ranks behind the front-runner, who had far outdistanced the competition. Their refusal to do so, even in the face of the virtual certainty of McGovern’s nomination, shows that the party leaders are unreconciled to their defeat and that they may prefer the entire party’s defeat to the election of a candidate who wrested the nomination without their approval. McGovern’s attempts to reassure the party bosses have for the most part been rudely rebuffed; in their eyes he is another Goldwater, an “extremist” with no chance of election.

The irony is that the Democrats’ only chance of returning to power is precisely to identify themselves with the disaffection abroad in the country. In a conventional campaign—the only kind the Democratic leadership knows how to organize—Nixon holds all the cards. Running as a great international statesman and peacemaker, Nixon can win on the strength of his ceremonial diplomacy, while confining his campaign to equally empty and ceremonial appearances. Faced, however, with an opponent who is determined to make an issue of the war, the economy, and governmental “credibility” in general, Nixon will revert to his former style, thereby confirming the long-standing popular suspicion that tricky Dick is not a man you can trust. To put the matter more broadly, the Democrats at this point can nullify the advantages inherent in controlling the Presidency only by appealing directly to popular discontent.

But since this also means reorganizing the party itself, the Democratic leaders can hardly be expected to participate enthusiastically in such a campaign. McGovern will have to win the Presidency the same way he won his party’s nomination—on his own, with his own organization, and with only perfunctory support from the unions and the party hierarchy.

A McGovern victory on these terms—here we come to the nub of the matter—would create a significant opening in American politics. It would set in motion popular forces which cannot be appeased by his own programs (and whose active support and pressure on Congress and the bureaucracy he would need even to make a beginning in re-allocating wealth and dismantling the military-industrial apparatus). Those programs are “extreme” only in the context of the total vacuity of other candidates’ programs. While their implementation would have consequences far from negligible for American society, they by no means embody the kind of comprehensive attack on the problems of neocapitalism that is required. They would probably create as much dissatisfaction as they would allay. Moreover, even their enactment is unlikely without various kinds of compromises.

Political conditions following the inauguration of McGovern might be somewhat reminiscent of conditions in 1933-34, when the New Deal acted as a stimulus to popular movements that sought to go beyond the New Deal and threatened for a time to overthrow it. The “revolution” that many observers predicted in 1934 never materialized, partly because the Roosevelt Administration made concessions to popular demands for such reforms as a graduated income tax and social security, partly because one of its leading spokesmen (Huey Long) was assassinated, and partly because the strongest and most effective wing of the left—the Communist Party—decided that communism was “twentieth-century Americanism” and gave uncritical support to the New Deal as the opening wedge of the socialist revolution; the very strategy Harrington urges today. It is in keeping with his general outlook that Harrington regards the disaster of the popular front as a piece of consummate political realism. The popular front strategy, he says, “worked better in the United States,” even though it was dictated by Moscow, than the sectarianism of the socialists.

Even if we set aside the socialists, who had their own problems, this judgment leaves us with the difficulty of explaining the collapse of the communist movement after the war and the ease with which it was expelled from the CIO. A better interpretation would be that the militant industrial unionism promoted by the CP in the late Thirties, unaccompanied by a militant politics or a critical view of American culture, left the party ideologically indistinguishable from American liberalism and to a considerable extent dependent on its fortunes. When liberals found themselves on the defensive after the war, they readily sacrificed their own left wing to the popular outcry against subversion, while the Party’s subservience to Moscow made it possible for it to be depicted as a foreign menace. As the left wing of the New Deal coalition, the communists were more vulnerable than they would have been as an independent political movement.

Whether a somewhat similar political situation in the 1970s would have a different outcome depends, in part, on whether the left is better prepared to deal with the new populism than the left of the Thirties was prepared to cope with the New Deal. The communists’ pratfalls in the Thirties, particularly their ungainly leap from the super-revolutionism of the “third period” (1929-34) to the ultra-reforming of the Popular Front, are an object-lesson in what to avoid. Merely negative lessons, however—even if these were clearly understood—would take the left only a certain distance toward the wisdom it needs. More than ever, radicals need to ponder their history.

In doing so, they will find in Michael Harrington’s book many of the insights they need to absorb. That Harrington’s book is not likely to provide reliable guidelines to current political practice does not invalidate its other virtues. Wisdom is not the monopoly of any particular political position. For that matter there is also much to be learned from the new populism, if only because it is closer to the country’s mood than the new left ever was. If radicals and intellectuals adopt toward this movement an attitude of superior disdain, they will show that they have not only learned nothing from their recent experiences but are probably determined to remain ignorant.

This Issue

July 20, 1972

-

1

See, for example, Norman Pollack, The Populist Response to Industrial America (Harvard, 1962); Walter T. K. Nugent, The Tolerant Populists (University of Chicago, 1963); and Michael Rogin, The Intellectuals and McCarthy (MIT Press, 1967).

↩ -

2

André Gorz, Strategy for Labor (Beacon Press, 1964), p. 60 n.

↩