Transpo ’72 was first planned as an air show, by the late Mendel Rivers of the House Committee on Armed Services. For a modest $750,000 of federal money, it would stimulate foreigners to buy American airplanes, and it would attract visitors to Dulles airport outside Washington, where it was to be staged.

The exposition, as held last month, had moments of aeronautical interest. The opening ceremonies at Dulles were performed by the president of Boeing and the astronaut Michael Collins, with displays by military parachutists in red, white, and blue silk. The show featured well-known figures from the world of defense politics—the so-called “distaff side of Transpo (“Women’s Lib Notwithstanding”) was handled by Mrs. Anna Chennault, identified as a vice president for international affairs of the Flying Tiger Airline. Demonstrations of modern transportation were interrupted regularly by Phantom jets flying by on their backs, at the level of the Transpo flagpoles. But Transpo also aspired to broader importance. At a cost of $5 million to the federal government (with about as much again contributed by corporate participants), and installed in a space of 300 acres, the show became a festival of Total Transportation.

Government officials described Transpo as the largest industrial exhibition in the history of the world, bringing together the finest “hardware and concepts” of the booming transportation industry, and the “products, equipment, techniques, and concepts that can solve today’s transportation crisis.” After a technologically troubled beginning, when a sudden wind blew down several new business pavilions and caused the Transpo asphalt (made from recycled garbage and sulphur waste) to disintegrate into clouds of bitter red dust, the exposition was a great popular success. More than a million and a quarter people toured the show, and traffic holdups snaked from all over Virginia to Transpo’s new prairie-like parking lots (acclaimed as “some of the world’s largest,” and “equivalent to forty miles of highway”). The hundreds of participating corporations showed Cadillacs, Mack trucks, trains, recreational vehicles, subway cars, boats, models of the F-111, hovering Coast Guard helicopters; and according to an ebullient spokesman quoted in the Wall Street Journal, it was “the biggest show the government has put on since World War II.”

He’s singing our song.

The most vaunted attraction of the new total Transpo was a display of four experimental mass transit systems, developed under government contracts by four different corporations. The systems consisted of small tram cars called “people-movers,” each carrying about twelve people and running on light tracks. All the cars were quiet and shiny and looked more like expensive refrigerators than like subway cars. Mayors from cities across America were invited to Transpo to ride on and order these cars, which could then be installed in, for example, airports, shopping centers, and down-town business areas.

The government agency responsible for the trams was the Department of Transportation’s four-year-old Urban Mass Transportation Administration, which is currently the government agency with the brightest financial prospects. Congress in 1970 promised it an initial $3.1 billion, and President Nixon’s recent economic pronouncements offer further subsidy. While other government departments parade their frugality, UMTA boasts that in 1971 it made 269 grants, bought 4,121 new buses, and doubled its staff. For Carlos Villarreal, the administrator of UMTA and a former Navy commander and California aerospace executive, Transpo was the culmination of this munificence. He has guessed that American cities will spend more than $30 billion on mass transit in the next ten to fifteen years. “Today,” he announced at the inauguration of Transpo, “marks UMTA’s entry into the space age of mass transportation.”

Of the four corporations that built UMTA’s Transpo tram systems, two are well-known aerospace contractors (the Rohr and Bendix corporations), one is Ford Motor Company, and the fourth, Transportation Technology, Inc., is described by UMTA as a “spin-off from GM.” UMTA’s 269 grants have the unmistakable smell of a space-age boondoggle, featuring a familiar corporate cast. (The former NASA center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been converted to transit research, and the Rand Corporation is undertaking civilian transportation studies.)

Mr. Villarreal of UMTA made his department’s relationship with the defense industry clear in an article from Aerospace magazine which was distributed at Transpo. He writes that ground transportation development requires and is already using the technological and managerial skills of the aerospace industry: “The scope of this achievement by aerospace firms may come as something of a surprise” (he is writing in a journal described as the “official publication of the Aerospace Industries Association”). “Let me give you some examples,” he continues, and lists mass transit projects involving North American Rockwell, the Grumman Corporation, Bendix Aerospace, Goodyear Aerospace, and Fairchild Hiller.

Transpo was most of all a bonanza for these and other diversifying defense corporations. Grumman displayed its latest, unpopular F-14A Navy fighter along with descriptions of a projected intercity air-cushion train. Ling-Temco-Vought provided details of its A-7E II Navy bomber, and of its newer activities, including acquisition of American Asian International, Inc. (“a Saigon-based company engaged in architecture, engineering projects, and skills training in South Vietnam”) and development of two rapid transit systems. A mock-up of the larger train was brought to Transpo from Dallas by truck, built on two mobile home frames; the public relations representative of Vought Aeronautics said that every time he stepped into it, “it was like a new world,” and that there was certainly plenty of market for such products.

Advertisement

Other aerospace companies were equally lavish in their Transpo displays, even though annual federal spending on mass transport is still worth only 5 percent of annual defense procurement. Boeing flew eighty dignitaries to the exposition in the first Boeing 707; it is meanwhile working on Department of Transportation contracts for small urban shuttles and for an advanced railroad car. (The award of a railroad contract to Boeing goaded Pullman, Inc., an unsuccessful bidder, to accuse the federal government of “playing wasteful politics by needlessly fostering the entry of companies from the depressed aerospace industry into the rail transit equipment business.” Pullman, which boycotted Transpo, later sued the Department of Transportation for allocating an $84 million commuter car contract to General Electric, another major defense corporation.)

Transpo’s most extravagant architecture was built by former defense contractors. A split-level hall in smoked glass belonged to Rohr Industries, which is described by Fortune magazine as “a shining example of diversification out of defense.” Rohr is now building trams, buses, hovering air-cushioned trains, cars for the new San Francisco subway and, probably, for the Washington Metro. During Mr. Carlos Villarreal’s Transpo press conference (inaugurating UMTA’s entry into the space age) two men sat down among reporters in the press room. They were easily identifiable by their large lapel badges as the chairman of Rohr Industries and his government relations officer. Mr. Villarreal happened at that moment to be describing the Rohr tracked air-cushion train. “Well,” said Chairman to Government Relations, “he’s singing our song.”

A Total Transportation Organization

The anticipated boom in government-supported mass transit has also been irresistible for the auto corporations. GM put on the largest display at Transpo, in a city of tents decorated with blue and white GM flags. A company spokesman spoke candidly about the public relations advantages of the show: GM’s “objectives for Transpo ’72 are to demonstrate that GM is a total transportation organization… [a] producer of hardware that will meet the needs of any federal, state, or local transportation system that is planned.” The GM pavilions featured buses and experimental “concept” vehicles, as well as Cadillacs, Vegas, and earth movers. Even the concept vehicles were demonstrated by short-skirted women models who, in the case of the micro-mini electric “XP-883,” towered about four feet above the cars on display. Ford built a geodesic dome and announced that it planned to install its Transpo tram system at Ford world headquarters—its two transit cars had been named “Rachel” and “Shirley” after two female secretaries in the Ford organization.

The Disneyland atmosphere of their pavilions did not entirely conceal the auto corporations’ uneasiness about non-automobile travel. A sober GM film discussing the future mass transit needs of Detroit affirmed the perpetual supremacy of the family car. Henry Ford II said that only a “limited portion” of the Highway Trust Fund should be used for public transportation, and then only for research into “new transportation concepts.” Chrysler’s exhibition claimed to demonstrate that the automobile, fitted if necessary with a new engine, but still private, will continue to be “man’s own personal magic carpet.” (Transpo also featured some of the auto industry’s less adventurous projects in personal transit. GM showed its new motor home. Something called the Recreational Vehicle Institute carpeted a large pavilion with green plastic turf. Both GM and Ford displayed “utility vehicles,” to be built in Malaysia and the Philippines for sale in what Ford called the “fast-growing vehicle market of Southeast Asia.” Ford’s Asian Fiera was described by the company as “a modern Model T for the masses”: “just one step up from the bullock cart or the bicycle,” but color-coordinated and available in six different models.)

Toward a Social-Industrial Complex

The preoccupation with new mass transportation shown by Transpo’s corporate participants is quite obviously a progressive development. One tram system for every half million Ford Thunderbirds is better than no trams at all. All trains are better than all F-14 fighter planes, and one can only welcome the prospect of the aerospace industry beating its swords into hovering trams. Yet the transportation systems now proposed by US industry and its government sponsors are very far from progressive when we consider some of their implications.

Advertisement

The way transport is organized is obviously important to the development of cities, yet the federal government seems about to abdicate responsibility for planning the politics of mass transit. Transpo entirely ignored questions of whether new transit systems should follow, or should try to inflect existing flows of traffic; whether the systems must be economically “viable” (and must therefore serve either people who can pay high fares or people whose time is considered economically valuable).

Most of the systems being planned support the present pattern of highway transportation: they make it easier to own an automobile. This is particularly clear in the case of the few Transpostyle tramlines already in operation or now being built. Almost all have been designed for new airports (in Seattle, Tampa, Dallas-Fort Worth), to move air passengers comfortably from parking lots to airliners. Another proposed use is for shopping and entertainment centers: trams would shuttle visiting suburban shoppers from distant low-rent parking lots to the high-rent entertainment area.

The principle of supporting automotive travel is likely to continue when the larger and more ambitious public tramlines now being developed are installed in cities. The schedules for new transport will be derived from an analysis of existing journeys. The new mass transit lines will be expensive to build and long-lasting, and they will connect city suburbs with downtown business areas. They will make the commuting journey from suburb to office to suburb easier and more pleasant. They will serve inevitably to encourage the creation of more and further distant suburban dormitories, and to reinforce a pattern of urban development and land-use based on a general use of automobiles. Meanwhile it will remain essential to own a car for journeys outside the dormitory-office corridor.

Most of the systems envisaged would also reinforce discrimination against the poor, particularly the poor who remain in the central cities, and would favor richer suburbanites, particularly suburbanite office workers. It seems likely that “personal” urban tramways will be installed, if anywhere, in the prosperous parts of prosperous cities. One found at Transpo no urgent interest in getting the people of, say, the Watts ghetto to work in other parts of Los Angeles, now reachable only by car. The two “advanced” automated railroads already built in the United States—the Lindenwold line outside Philadelphia, and the forthcoming San Francisco BART subway—both benefit predominantly prosperous commuters.

Under the new system, industrial workers trying to get from their homes in the central city to suburban factories at 8 AM might find several thousand personal trams going in one direction with perhaps two or three heading toward the suburbs. There would be no trams at all to take suburban factory workers to industrial jobs in other suburbs. Comfortable mass transit could become a luxury for the enlightened suburbs, while most of the poor continued to choose between irregular buses and an inconvenient, polluting car, by then probably subject to prohibitive taxation within urban areas.

Such discrimination is not surprising unless “mass” transit is treated as an absolute good. Public transportation could be used to redistribute wealth and opportunity, and to redesign cities. But the suburban tram lines as conceived at Transpo would not be likely to have this effect. This was shown clearly in a recent speech by Mr. Simon Ramo, called “Toward a Social-Industrial Complex.” Ramo, a vice president of the TRW aerospace corporation, a member of the official Transpo committee, and a prominent prophet of the “aerospace community,” evoked the possibility that existing military-industrial, government-business relationships will soon be replaced by a coalition of government planners and corporate “social technologists.”

A major activity of the social technologists would be to reorganize urban transport. “Substantial” government subsidy would attract private investors, and the enterprise could be so organized as to yield a generous economic profit both to the investors and to the government. Ramo writes that the suburban commuter “leaves his investment to stand all day in the parking lot.” “Tired even before he starts, his forty-hour work week accomplishes thirty hours worth, but it takes sixty hours portal to portal.” “The productivity improvement, the economic payoff potential, is sinful to ignore.” The message is: Mass tramlines can be profitable—when they are installed for the benefit of people whose time and psychic virility have a high dollar value.

It will be interesting to see which American city is first to install a “personal rapid transit” tramline (and to take advantage of the proposed two-thirds federal financing); and to see what political decisions it will make about how, and by whom, the system will be financed, and who will pay for and use the new trams. The corporations which designed the Transpo tramlines seem unconcerned about such questions of cost and organization—their hardware is apparently built for installation anywhere. One foreign city-planner who toured Transpo has said that he visited each mass transit pavilion at the exposition without finding a single company representative who could answer his simplest questions about the costs and fares estimated for the tramlines.

Yet modern corporations will in the future be eager to design the “software” and social organization for transit systems. GM, for example, is now rapidly expanding its staff of sociologists and city-planners. And even their present hardware looks biased toward a prosperous market. Transpo’s gleaming, high-technology modules seem designed to seduce the sophisticated commuter, sitting jadedly in his Buick or Volvo. As another foreign planner put it, cities will need “technological innovation to catch the imagination of the voter.” Meanwhile, the systems will use a maximum amount of capital—profitable and “technologically innovative” hardware—and a minimum of labor. They will run almost completely automatically, and they will provide few extra jobs. Their operating costs will be small, but the initial prices charged for the trams, tracks, and computer controllers will be enormous.

It seems possible, and dangerous, that the US government, now so enthusiastic about federally sponsored transit technology, will delegate responsibility for its application to city administrations; and that the cities will let that responsibility devolve upon corporate contractors. A mayor could ask GM or Bendix to deliver and install a complete system of urban mass transit, with little chance that such a system would seriously reduce the city’s dependence on autos or respond to criteria other than those of strictly economic return. Mr. Ramo’s Social-Industrial Complex could very quickly become a social monster, shielded from criticism by the assumption that all public works are worthy. Public transportation is too important to be left to Ford, Boeing, and Rohr.

Transportation and Civilization

The pavilions of Transpo were decorated with the apothegms of thinkers from Kipling to Nixon about the (intimate) connection between transportation and civilization. These quotations raise some questions about the Transpo approach to mass transit. The planned systems may reinforce social injustice—will they also create greater and greater, vainer and vainer needs for transportation? If commuting becomes easier, will more and more time, resources, and energy be used up on the journey to work, the journey to the shopping center? Will these journeys allow people more choice between jobs, or between supermarkets—or just more miles to be wasted?

During Transpo week, Henry Ford II told a Washington audience that 20 percent of the US GNP is spent on transportation—$1,000 for every man, woman, and child in America. Of that money, $800 is spent on motor vehicles. One out of every ten American workers is employed by the trucking industry (as the powerful American Trucking Association pointed out at Transpo, in a pamphlet which also noted that 99.44 percent of all materials arriving at Transpo came by truck: “the world’s first total transportation exposition—and it all arrived by truck”).

These statistics are no matter of national pride. It should not be impossible to discover, for example, whether certain journeys are unnecessary, and could be replaced by tele-communications contact, or whether certain movements of freight could be replaced by better methods of storage. It should not be unthinkable to consider discouraging the centralization of jobs and the suburban dispersal of cities, to consider that cities might by made more tolerable for all and that people might even live near their work. It is, in fact, also essential to reconsider the Kipling/Nixon equation of civilization and transportation.

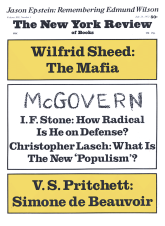

This Issue

July 20, 1972