Berger and Tournier have almost as much in common with each other as Webster and Tourneur have, those companions of the Jacobean Literature syllabus. And perhaps they also have something in common with Webster and Tourneur. Both their novels relate historical crises—respectively, the First World War, together with certain disturbances that preceded it, and the Second World War—to legend, and to the activities and fantasies of a heroic individual. Berger would be likely to sympathize with Tournier’s reference to “the stupid massacre of ’14-’18”; both try to explain such stupidity. Both novels use the image of a phallic Cyclops, of a penis with an eye in it, both invoke the shade of Don Giovanni, and these and other coincidences of myth and metaphor could suggest that both contain an element of vogue, and that the fashions and forces that shape them are at no great distance from one another. Different as they may now appear, they may eventually be seen to belong to a category no broader than that of the ethos of the Jacobean stage.

Meanwhile the differences between the books, which are no less important, can be expressed in Jacobean terms. Tournier has a little of Webster’s ready rhetoric and self-indulgent liking for the grotesque; Berger describes a sexual Machiavel whose seductions might look like a principled revenge against the ruling class.

John Berger’s book is “for Anya and for her sisters in Women’s Liberation,” and its hero, G., is a sort of Don Juan who liberates his women and subverts a merciless social order dominated by the search for colonies and capital. G. is the illegitimate son of a candied-fruit merchant in Livorno and of a rich American woman: his mother soon abandons him and goes off to serve the Fabian Society. The boy is looked after by his Aunt Beatrice in an English country house given over to the worship of horses, an ambience of centaur-squires. At puberty he watches the revolutionary fighting of 1898 in the streets of Milan, which occasions an illumination—to do with his not wanting to die. He goes to bed with his aunt, and embarks on a career of seduction. The arrival of aviation, which attracts his attention, does not dampen his sexual ardor: during the first flight over the Alps, which ends in disaster for the heroic aviator Chavez, G. is intent on flights of his own with a chambermaid in a nearby hotel. After that, he engineers the conquest of Camille, wife of an industrialist, Hennequin, who wings him with a revolver. After that:

He made his plans quickly. He would go to Paris, visit the Hennequins, make a point of ignoring Camille, reassure the husband and would quickly begin an obvious, public affair with Mathilde Le Diraison. In this way he would avenge himself on Hennequin by making the whole shooting incident appear ridiculous….

He would then disappear—quickly, no doubt—from the Hennequins’ circle.

The Great War breaks out and presently reaches Trieste, where G. is nominally engaged in undercover activities. He is also engaged in seducing a banker’s wife and in performing a Pygmalion on a Slovene peasant girl, Nusa, whom, for social revolutionary reasons, he takes to a grand ball: Nusa, though unseduced, can be said to complete the catalogue of his specified conquests. When Italy enters the war, riots ensue in the city, during which G. is dropped in the harbor and drowned. Just before his death another epiphany has occurred, which causes him to think: “Why not be dead?”

An interesting English review by P. N. Furbank states correctly, I think, how G.’s seductions are meant to be regarded. They are salutary; he is “a thaumaturgic sexual healer.” Those of his women who are of the bourgeoisie are immured in heavily ornamented houses, each stuffy room of which is charged with possessions, and they are themselves possessions and behave accordingly. Like the women in the portraits of the past which Berger—who is chiefly known, of course, as an art critic—has lately been discussing on BBC Television, they signify and attest to ownership. G. does not own them. Instead, he sees them. And this is their salvation. He rescues them from the condition of the lady in a limerick attributed to Dylan Thomas:

The night that I slept with the Queen,

She said as I murmured “Ich

dien”:

“This is Royalty’s night out,

So please switch the light out.

The Queen may be had but not seen.”

Berger’s thesis, Furbank says, is this: these women “need, not to be surveyed like possessions, but seen. And so deep is their dungeon, so thick-walled is their prison, that the only angel which can release them is the penis, for the penis alone can ‘see’ them.”

Advertisement

There is plenty of warrant for this interpretation in the text: “It is her solitariness—her solitariness alone—that he recognizes and desires. He has led her from her conjugal bedroom, from the overfurnished apartment, from the street in which the curtained windows are so still that they might be carved out of stone, from the overread pages of Mallarmé….” And again: “He stares at her with eyes more intensely fixed than any she has ever imagined.” And again:

She has not said to herself that she loves him. He has convinced her of only one thing. Unlike any other man she has ever encountered, he has convinced her that his desire for her—her alone—is absolute, that it is her existence which has created this desire. Formerly she has been aware of men wanting to choose her to satisfy desires already rooted in them, her and not another, because among the women available she has approximated the closest to what they need. Whereas he appears to have no needs. He has convinced her that the penis twitching in the air above her face is the size and colour and warmth that it is entirely because of what he has recognised in her. When he enters her, when this throbbing, cyclamen-headed, silken, apoplectic fifth limb of his reaches as near to her centre as her pelvis will allow, he, in it, will be returning, she believes, to the origin of his desire.

The novel can be quite sententious, and there is some fine writing here which creates, doubts: what does it mean to credit someone with absolute desires who has been declared to be without needs? What does it mean to say that his desires are not rooted in him, as are those of the other men mentioned? But the general picture is clear enough.

If G. is God’s gift to women, it’s a gift that is rapidly removed from each in turn, though these lightning departures do not spoil the miraculous cures. His departures resemble those of the traditional Don Juan. The traditional Don Juan was a subversive force by virtue of his offenses against a system whereby women were a form of property: he was a thief—perhaps a principled thief. But he was not a liberator of the women he stole. He could, in fact, be thought to give support to the ownership and subjection of women in much the same way that Al Capone could be called a capitalist. Don Juan can only be enlisted in the cause of Women’s Liberation by virtue of a rather severe adjustment of his traditional role, and I’m not sure that any such adjustment takes place here.

If G. is a sexual revolutionary who is also a social revolutionary, his subversions and his seductions are seldom seen to coincide. Not only that, the healing effects of his seductions are largely a matter of assertion on the writer’s part. I wonder how many sisters would accept that a brief and beady inspection by a wandering penis should be their guarantee of freedom. The thaumaturgic properties of the fifth limb—is this “the purest Women’s Lib doctrine,” as Furbank alleges? At times, the author of this book reads like an involuntary male chauvinist who is on the side of Women’s Liberation because he is on the side of revolution. “There is a look which can come into the eyes of a woman (and into the eyes of a man, but very rarely) which is without pride or apology, which makes no demand, which promises no adventure.” If there is such a look, it is likely to be in the eye of the male beholder. Women’s Lib doctrine would presumably be that there is no such look.

The book has an interest, however, which can’t be argued away like this. It was a good idea to bring together the roles of seducer and subversive during a period when there seems to have been a powerful relationship between greed for money and the glorification of adultery: a powerful relationship, both of attraction and revulsion, between business killings and lady-killings. G. isn’t exactly a person: he is mythical and anonymous, and a striking last passage compares his death to the lapsing of a wave in a tossing sea of human experience. But in so far as he is a person, he is, somehow, a plausible one, and the career of this uprooted Anglo-Italian bastard gent, devoted to sex and social outrage, may be felt to represent a likely story.

For all that, there is oddly little sense of period in the book, and this may possibly be related to the lack of any element of enjoyment, affection, or humor in G.’s love affairs. The very riots are sexier: in fact, it is the riots that are sexy. What humor there is is of the accidental kind: “I am enveloped in the astonishing silence of my breasts.” Not long ago Alberto Moravia turned a penis into a character in a novel, and now Philip Roth has a character who turns into a breast. Moravia was being funny, Roth disclaims any “crapola about Deep Meaning”; Mr. Berger’s purpose in devising a phallic eye seems very different from theirs.

Advertisement

But perhaps such a want of feeling and absence of atmosphere are not odd at all, but just what you’d expect from a novel which is an essay in the French style, replete with examples, explanations, poems, metaphors, and incidents, many of them occupying paragraphs of their own within a frame of white space, like pictures in a gallery: G.’s liberations are abetted by typography. Some of the narratives and small items are very successful—the failing bond between G.’s parents, for instance, and the Chavez episode. But some of them are not. This isn’t a tall story, but some of its explanations and assertions are (for me) quite tall. “This combination of surprise and of expectations being precisely fulfilled is unique to moments of sexual passion and is another factor which places them outside the normal course of time.” Mr. Berger occasionally gives the impression of lecturing, and is self-confident about difficult matters. Some of the poetic writing is tall too: “Time whose vagina is moist with timelessness.”

Both these writers, as I’ve said, play with the idea of a penis with an eye in it, and at one point Tournier’s ogre—the gentle-giant pederast, coprophile, crank, and virtuoso, Abel Tiffauges—compares himself to Don Giovanni. Shortly afterward the phallic Cyclops rears his head. Tiffauges drives about in his car with a camera “wedged between my legs. I enjoy being equipped with a huge leather-clad sex whose Cyclopean eye opens like lightning when I command it to look.” But it seems that the two writers differ sharply about what is involved in the activity of seeing somebody. For Tiffauges, “It is plain that photography is a kind of magic to bring about the possession of what is photographed.” He goes on: “As I don’t possess the despotic powers to procure me actual possession of the children I’ve decided to get hold of, I make use of the snare of photography.”

Whereas Berger’s Don Giovanni sees in order to save the person seen from the plight of being a possession, Tournier’s Don Giovanni sees, and snaps, in order to possess. G. does not, of course, take pictures, or bear away trophies or scalps from his conquests. The two characters are doing different things. But there are definite resemblances between their activities as seers of a sort. And the conflicting interpretations put on what they do, and on its metaphorical significance, are enough to suggest that here we have a tribute to the elasticity of metaphor when it is used in a tricky or coercive fashion. Both novels deal in legend, or legendariness, and to some degree, too, in legerdemain.

Tiffauges’s consciousness pervades The Ogre, and extracts from his Sinister Writings are embodied in the narrative. He is not only a metaphoric but a phoric animal. Let me explain. He is a large, muscular French recluse who has a bad time at school between the world wars, but acquires a sense of destiny. He comes to love children and wishes to carry them about on his shoulders: this obsession with “phoria” or carrying makes him more of an Atlas or a St. Christopher than a Cyclops, let alone a Don Giovanni. He has also acquired a love of wounds—purple, pulpy wounds with lips and coursing liquids. When the Second World War breaks out, he joins the French army and lovingly tends carrier pigeons (perhaps because the French for carrier pigeon is pigeon voyageur, that’s one phoric trifle that goes unconsidered by M. Tournier, who is normally very keen on analogies and verbal ploys). Then he is captured and taken to a camp in Prussia, where his destiny enters a new phase.

Apart from the business of phoria, Tiffauges believes in a certain process of inversion. His obsessions appear to match some of the Nordic superstitions which the Nazis have incorporated into their mystique: but this Teutonic material is experienced as a series of “malign inversions” of the Tiffauges material. Nevertheless, his move nach Osten provides him with a feast of phorias and euphorias. His bliss begins in the prison camp itself, where he befriends a blind elk, and continues with his translation to an estate where he serves Goering in the capacity of huntsman, witnessing the convulsions of the Reichsmarschall’s backside as he gropes in the entrails of a slaughtered deer for the magic testicles. Life is a load of magic testicles in this gothic version of Hitler’s Germany. It is also one disemboweling or impaling after another, and Tournier’s Jacobean proclivities bring about a spectacular Act Five holocaust when Tiffauges shares in the Nazi Götterdämmerung and his favorite German boys arrive at a “Golgotha.”

By then he has gone to work at one of Hitler’s youth academies—or Napolas, as they were known, apparently. This one was formerly a castle of the celibate Teutonic knights. Here Tiffauges is in his element, riding phorically about on a sturdy horse in order to collect cadets, a fulfilled and healing centaur ministering to his hundreds of blond youths, on whom the curse of Nazism, though not yet that of puberty, has descended. At the last moment, as the Russian tanks are rolling toward the lads, he picks up a Jewish boy who has escaped from a concentration camp, and nurses him in an attic. Ephraim, perhaps, teaches him a livelier recognition of the malignity of the Nazis. But Ephraim is also his undoing. Fleeing from the Russians, the pair, pig-a-back, end up in a marsh and Tiffauges sinks to his death, passing into the condition of one of those prehistoric sacrificial victims who turn up from time to time in the acid soils of Northern Europe, excellently preserved, their last meal of cereal still crouching in the intestines. Meanwhile Ephraim, a star, twinkles on high. Such is the book which Janet Flanner regards as the most important to appear in France since Proust.

Tournier is the author of the much-admired Robinson, and an English reviewer has now recalled that this “dazzling” novel showed the rational Crusoe of the Enlightenment regressing toward a “truer enlightenment of primitive blood-knowledge”: it also ended, like the new one, in the sky, in “solar ecstasy” (Tournier’s words). The Ogre is a very clever book in its belletristic way, and the translation reads extremely well. It may not be a likely story, but it is an absorbing one. Tiffauges’s obsessions—a cornucopia of the ocular, the cloacal, of celibacy, heraldry, therapies, wounds, beasts, boys, and twins—are conveyed in an alliterative rhetoric of rare words and allusions. There are words like suint (according to the dictionary, “dried perspiration in wool [Fr.]”). And sentences like: “The horse is not only the animal totem of Defecation and the phoric beast par excellence. The Anal Angel can also become an instrument of ravishment and rape, and, as the rider carries his prey phorically in his arms, rise to the level of superphoria.” Tournier’s primitive dumb ox of a hero has been awarded the pen of a French man of letters—the sort that wins the Prix Goncourt, as Tournier has with The Ogre.

Tiffauges is rendered as a being who is himself partly malign. He ends in the earth, not in the sky. He possibly corresponds to the Erl-King in Goethe’s ballad, which figures in the book, as well as to the equestrian father in the ballad, and he is an Erl-King who comes to a sticky end. All the same, while the novel contains the self-disclosures of a type of erring or aberrant sadomasochistic exalté, it also seems to make sense to read it as a celebration of his fantasies. (I notice that M. Tournier is an enthusiastic photographer.) There is clearly some renewal here of the profundities and affirmations of Robinson, and I imagine that it wouldn’t be easy to say why one should be dazzled by the first book and repelled by its successor.

The unsatisfactoriness of The Ogre lies mainly in the weakness of the distinction it draws between the malignity of the Nazis and the comparative benignity of this creature who achieves an apotheosis in the Nazi heartland. And its picture of the malignity of the Nazis is very dubious anyway. Hitler’s G. is presented as a country of the mind, a country without politics, tenanted by evil magicians poring over pints of blood and suint and measuring skulls and noses in the interests of purity. Alfred Rosenberg’s contribution to the Reich is talked about; Albert Speer’s is not. Tournier documents the behavior of his cranks and pedants with reference to the evidence obtained for the Nuremberg Trials: but the evidence submitted there hardly tends to show that the behavior of these cranks was central to the history of the Reich. Admittedly, Tournier is not writing a history of the Reich. But it would appear that he has misrepresented that history while using it as a setting for an account of a fairly exotic psychological state.

In an agony of tenderness, Tiffauges broods over the innocents whom his fellow cranks, who are the wrong sort of cranks, have consigned to a massacre. His madness is full of Deep Meaning; theirs is full of cruelty: yet they have a deep something in common. It is all too mysterious and magical for me. And I doubt whether that something will assist an understanding of German nationalism in the time of Hitler, any more than the prophetic works of Yeats assist an understanding of Irish nationalism. Tournier’s imaginings come no closer to the condition of life in Nazi Germany than his Academician’s prose does to the delusions of a supposedly ignorant obsessional.

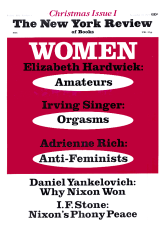

This Issue

November 30, 1972