that ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia

—Finnegans Wake

In spite of brilliant deviations like Three Trapped Tigers and A Hundred Years of Solitude, naturalism remains the dominant mode of fiction in Latin America. It is a naturalism that accommodates myths, symbolism, streams of consciousness, elaborate narrative techniques, but naturalism, nevertheless, is what it is.

All writing presupposes a particular relation between the writer and the reader. In naturalistic fiction the writer is usually assumed to be the reader’s delegate. He sees more than we do, thinks more, and writes better. He has more imagination, more sensibility: he is our voice. His job is to find the right words, to name and describe events, people, objects, emotions, sensations. Writers can be good or not good at doing this, but if they choose this relation with their readers, they lock themselves up in literature, confine themselves in a closed, static universe of literary verisimilitudes and probabilities. If they live in our century, they have resigned themselves, whether they know it or not, to being minor writers.

Of the writers under review here, Asturias (from Guatemala), Fuentes (from Mexico), and Donoso (from Chile) are minor writers in these terms. Their prose sets out to capture the world—the light of a tropical morning, the shine on a businessman’s suit, the quality of life in a run-down brothel—and succeeds. But the success is a limitation and the coherence of these novels an admission of smallness: Asturias’s The Eyes of the Interred, Fuentes’s Holy Place (the first of the three narratives in Triple Cross), and Donoso’s Hell Has No Limits (the second of these three narratives) are only novels, bundles of words in pursuit of reality, nets that will catch only fish that are already dead.

This is not to say that the other writers under review are major writers (although I think the Brazilian Machado de Assis and the Argentinian Cortázar are), merely that they have not settled in advance for a minor mode. If we think of other models for the relation between writer and reader, some of all this will perhaps become clearer. Many writers refuse to see a disparity between themselves and their readers, and replace the suggestion of a delegation with an implied parallelism. They assume either that they themselves are also readers, deciphering the universe in much the same way as their readers are unscrambling their text: or that the reader is also a writer, creating worlds in his mind much like the one that is being assembled on the page before him. Or both, of course.

Borges, Bioy Casares, Machado de Assis, and Cortázar are readers, intent on what Cortázar calls “the old human topic—deciphering.” We may also think of Henry James, who constantly spoke of “making things out,” or of Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, reading signatures in the sand of an Irish beach. This is fiction which is modern in its epistemological concerns but also linked to the nineteenth century in its taste for patterns that come out, as in detective stories, as in Dickens, for the final unfolding, the configuration which constitutes a deciphered meaning.

Joyce, on the other hand, is also a writer behaving like a writer, making writing itself into a metaphor—we watch him piling up words against silences in Ulysses, spinning out language in Finnegans Wake. He finds company in Latin America in writers like Cabrera Infante, author of Three Trapped Tigers, and Severo Sarduy, author of From Cuba With a Song, the third of the narratives in Triple Cross. In a critical essay Sarduy appears to answer Cortázar’s image of a code with a new emphasis—on the making of a code, or on the putting into code. He calls for “a new literature in which language will appear as the space of the act of ciphering, as a surface of unlimited transformations….”

Joyce, though, like the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier in The Lost Steps, like García Márquez in A Hundred Years of Solitude, insists on both the coding and the decoding, insists that the readers play both games, make themselves sufferers from that ideal insomnia, as baffled and as creative as the writer himself. It is not a question of our collaborating imaginatively in the fiction. We do that anyway, if we are reading properly; that is what reading is. It is a question of our solidarity with the writer, or rather, of the writer’s solidarity with us, the single fate that links us. We all have to read the world, writers and the rest of us, and we all have to find words for our readings. Not the right words. The perspective I am suggesting recognizes only that some words are better than others. All are provisional, pointers only, intimations of reality, not boxes or cages; and all retain in their arrangement an irony which escapes naturalism.

Advertisement

Let me give some examples from the books involved here. Here are Asturias, Fuentes, Donoso:

They spun around in one spot, tight together, incrusted, in a drowsy haze of drink and cigarettes, kissing, talking, licking each other like primitive creatures caught in the conflagration of the origins of the world, of which jazz was the image….

…she spurs the horse and there, forever, are her aqueous dark eyes, the only eyes which by virtue of darkness create light, as if to deny something were the only way to finally conquer it.

The poplars trembled. If the wind blew any harder the town would be invaded by yellow leaves for at least a week and the women would be sweeping them all day from everywhere, the street, the alleyways, doors and even from under the beds, to gather them in heaps and burn them….

Every linguistic feature in these passages, including metaphor, paradox, and hypothesis, is directed toward making us see: see a bar in a tropical town; the eyes in a face in a movie; a season in South America—naturalism. And such writing treats states of mind in the same way, as phenomena to be described, named.

In Machado and Cortázar, on the other hand, the language shows us not the world but a mind looking at the world, not a mood but an activity. It mimes the mind’s movements. The writer is no longer our delegate, he is merely doing in front of us what we do on our own all the time. He is trying to make sense of things, and he no longer seems to be working so hard as the naturalists were. Machado:

My stay had been far too long, and in spite of our intimacy might begin to appear indiscreet. It was time to leave; I wanted to leave and stay at one and the same time, an impossibility; thus I passed several moments of contrary impulses.

Cortázar:

…and that, Juan said to himself, drinking his third glass of Sylvaner, was basically all the summing up he could best utilize, putting it that way, of what had happened to him: a lesson of things, a display of how once more the before and the after had fallen apart in his hands, leaving him a light, useless rain of dead moths.

For completeness, I should quote the Cuban Sarduy, the writer as writer, whose world is shown in the making. We respond here, it seems to me, to the movement of the writer’s imagination, not to what the imagination proposes. There is nothing to see, nothing even to read, in the sense of deciphering:

They are fluorescent, they are acetylene, they are drums that hypnotize birds, they are helicopters, they are chairs at the bottom of an aquarium, they are obese eunuchs, their tiny sexes among pink flowers, they are piranhas, leprous angels who sing “Metamorphosis, metamorphosis,” they are two unhappy creatures who just wanted to escape a retired Priapus. They are forgiven.

A case of “unlimited transformations,” as Sarduy says.

Asturias is a proficient, prolific, rather dull novelist who seems to have got the Nobel Prize for having a kind heart and for sympathizing, at least in his books, with the downtrodden. The Eyes of the Interred, first published in Spanish in 1960, is the third part of a trilogy, following on Strong Wind and The Green Pope, a long story of strife and turmoil in the banana plantations. Here the threat of a general strike brings down the president of the country, but the revolutionaries know they have not won their fight yet. “No, not yet, because they were only on the threshold of that great day…,” the day when the dead, who were buried with open eyes, the legend says, will be able to close their eyes in peace.

The book is skillfully decorated with symbols and myths, all the characters are convincingly realized, in a bookish way, and the only question in my mind is why Asturias should have bothered to write it, and why we should bother to read it. The lovers reborn in a cave, the assassin who not only sends his girl flowers but gets discovered before he has to do any assassinating, and turns out not to be all that keen on killing anyway (he just stumbled into that part of the plot, and no one else seemed to want to do it), clearly locate this novel in the realm of sentimental fiction, the place where we sit and securely contemplate a simplified world, hoping for an end to injustice, so long as we don’t have to do anything about it, or even look at it from very close up. The Asturias who emerges in the interview with him which appears in Rita Guibert’s Seven Voices is just what the fiction would lead you to expect: grand, pompous, occasionally impressive, and often silly, given to talking about his “little native land,” and convinced that an exhibition of Mayan artifacts, which he arranged in Paris, was a redeeming political act.

Advertisement

Fuentes, on the other hand, is a remarkably intelligent man who can’t decide what to do with himself. Holy Place is a camped up pursuit of camp, littered with brittle quotations from Borges, Fitzgerald, Sade, Huysmans, and Susan Sontag. The narrator is the son of a famous Mexican movie star, haunted by his mother, and we are meant to see several possibilities for the myth of Ulysses here, the central one of which seems to be that Telemachus will marry his mother while his father is away. In any case, Penelope turns into Circe when her son sees her having an affair with his old school friend and spiritual twin.

The novel doesn’t get off the ground because it is too snarled up in cleverness and paradox, and hampered by an alarming poverty of imagination. The narrator has Nadar’s portrait of Baudelaire in his room, his safe, holy place where he seals himself off from the desecrations of the world, and a painting of guess who else: Sarah Bernhardt. At one point he reaches for the “inevitable” books he keeps by his bed, and the word “inevitable” rings with an unfortunate clamor. These are not the books this character was certain to have, but the books that Fuentes, fatally and feebly, was certain to endow such a character with: Les Caves du Vatican, A Rebours, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Quest for Corvo, Cardinal Pirelli. Everything in the book smacks of this deadening predictability.

José Donoso’s Hell Has No Limits, however, is a masterly little fable about the strangling ambiguities of life in a poor, dying Latin American town. La Manuela is an aging queer, fluttered by the reappearance of the bullying truck driver who pushed him around a year ago. La Manuela and his daughter, who run the local brothel, wait for the man to come. But the truck driver is in debt to Don Alejandro, the local landowner and politician, and is trapped by his past. He grew up on Don Alejandro’s estate and can’t free himself from this false father. The men of this village waver, then, between the brothel and the hacienda. La Manuela gets out a tattered red dress and dances flamenco for the man when he comes, but is later beaten up and crawls off toward the domain of Don Alejandro for safety, thereby clarifying the connection which has been building throughout the work. The failed father, the father who would rather be a female dancer, and the fierce father, the one who eats his children, are in secret league, on the same side of the fence, and always have been: La Manuela and Don Alejandro, the fatherless brothel and the paternalist rule.

I’m making the book sound more schematic than it is. These allegories drawn from the confusion of sexual and parental roles are certainly there, but they are firmly embedded in a naturalistic setting, a place we can see. The meanings grow by suggestion, by intimation, are not set as roughly across the text as I have set them in this crude summary.

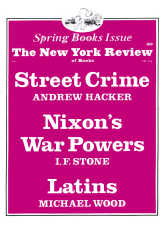

With Severo Sarduy’s From Cuba With a Song we leave naturalism a long way behind and approach what has been described by Roberto Gonzalez Echevarría as “an attempt to reduce Cuba to a textual space where the entire range of Cuban speech is contained simultaneously—a sort of living archeology.” I know nothing at all about the range of Cuban speech, but that must surely be an exaggeration. What we have here are three short fables about absence, loss, distress, dilution. A comic-opera Spanish general looks for a Chinese singer in a kind of surrealist knockabout dominated by two frenzied, bewigged ladies known as Help and Mercy. An awkward pair of narrators try to tell the story of a mulatto woman who was the mistress of a Cuban politician, and wrote a ten-line poem as her own epitaph. A quick cultural and religious history of Cuba is sketched, which races allusively from medieval Spain through Spanish mysticism (“In this passage, and many others, may Saint John forgive me,” we read in a footnote) and over the sea to tropical languor, winding up with Christ, who is also Castro, trekking across the island from Santiago to Havana.

From Cuba With a Song is something like a Spanish-language equivalent to Queneau’s Zazie dans le Métro, a work that is both parody and celebration. The text, for example, mocks the writer: “Good grief! That’s all we needed: God the writer, who sees all and knows all before anybody else does….” But then the writer also has his moments, and explains to his characters that he can’t give them everything: “Well, dear, not everything in life is coherent. A little disorder with the order, I always say.” The verve and variety of this writing remind us that works which take language as their hero don’t have to be dead or divorced from reality. They may affirm, as this work does, and as Joyce does, the multiple human energies of words themselves, which are as free and cluttered as we are, caught up in culture but also free to play around.

From ciphering to deciphering. Bioy Casares is a close friend and collaborator of Borges, and Borges’s influence is very clear in his work (if we knew more about him, we might also say that his influence is very clear in Borges’s work). He is in one sense more inventive than Borges, better able to create a plot and sustain a narrative. But he appears to lack Borges’s eeriest and most important gift: the ability to suggest the uncanny lurking in the quietest, most unlikely corner of a house or a phrase. Diary of the War of the Pig has the logic of dream, or seems to invite such a logic, but it doesn’t have the intensity of a dream, although it seems to be seeking it.

The young, we discover, have grown impatient with the old, and are killing them and beating them up and putting them away. A young man shoots an old man, and explains to the court that he was so irritated by the sight of a bald head, and by the old man’s slow reflexes, that he just couldn’t resist the temptation to kill him. The jury understands, and he is acquitted.

What is interesting about the book is less its premise and the competent but uninspired execution of its consequences, than the psychology of the old men, who are busy either trivializing the whole thing, arguing about whether the war of the pig ought not to be called the war of the hog, or caving in wholesale to the arguments of the young, secretly agreeing to despise themselves, to feel ashamed at the course of nature. Bioy is plainly thinking here of that damaging impulse so common in persecuted groups, and memorably dramatized in Kafka: the impulse to believe that your persecutors are in some sense right about you.

Whenever a work gives the impression of trying to create a summa, Cortázar’s character Morelli thought in Hopscotch, one must quickly demonstrate that the reverse is being attempted, the creation merely of remains. What gets written, for Cortázar, is what is left when the excitement is over, when the epiphany or illumination that started you writing has gone, has disappeared among all the words and phrases you have thrown round it.

A character in 62: A Model Kit is engaged in the same pursuit. Juan, in love with Hélène, thinks he has seen, for a moment, how everything falls into place, glimpsed a real order of emotion and events which would allow him to connect a set of his own fantasies about vampires with a French dollmaker who is in the habit of inserting gloves, money, and other less reputable objects and substances into his dolls, with the light over a Paris street at a certain moment, with a boy who died in hospital under anaesthesia, with himself having dinner alone one Christmas Eve: a configuration which tells him that Hélène is a vampire and he is the victim, that both of them are being propelled into these postures by forces which have nothing to do with their conscious or unconscious wills. But then he also knows that this is not true, that he and Hélène are who they are, are choosing to present themselves to each other in this cruel relation.

The title of 62 refers to a chapter in Hopscotch, where Morelli thinks of a book in which psychology would be replaced by a theory of the chemical nature of thought so that characters would be driven by the organic, cellular needs of life itself, pushed into love or metamorphosis for no apparent reason. But Cortázar, as distinct from Morelli, knows that the attractions of this secret, impenetrable order are sinister and inhuman and not to be flirted with, like the attractions of perfect symmetry or the abolition of time in Borges. So he places this speculative possibility in a novel where the human particularity of events cries out against this reduction, pleads to be understood by the old, ordinary psychology.

Marrast, a French sculptor, loves Nicole, who loves Juan, who loves Hélène, who likes Celia, who is having an affair with Austin. The whole group is linked by such chains, and the only sane attitude seems to be a certain zany aloofness, as represented by the Danish girl Tell. Marrast and Nicole are in despair because their affection has gone sour and yet they can’t leave each other: another form of vampirism. “I put the license of a torturer in your hands but so secretly that you have no way of knowing,” Nicole says. And in the face of these dark, circling realities, conveyed in a fast, obsessive prose that slips in and out of the minds of different characters, in and out of fantasies, without any sign of transition, the characters convert themselves and their lives into jokes.

Marrast anonymously invites a group of people to gather in front of a nondescript painting at the Courtauld Institute in London. The director is alarmed by the crowds, and thinks the painting is about to be stolen. Polanco, an exiled Argentinian, plays with an electric razor in a bowl of porridge in order to find out by analogy whether he will be able to use a lawn mower as an outboard motor. He greets an interruption with a sigh, and “the same face that Galileo assumed under similar circumstances.”

These characters, like Cortázar as he presents himself in Seven Voices, pretend to be amateurs, playing at their jobs, at their public lives, saving their real energies for their secret affective concerns (Cortázar saves his, apparently, for the consolidation of the Cuban Revolution). And all of them, again like Cortázar in the interview, achieve a real but fragile charm on the basis of their playfulness, without for a moment convincing us of their amateur status. There is a lie here, an illusion. The characters of 62 deny their despair in the same way that Cortázar denies his seriousness about his writing, and there is something touching, if a little silly, about such extremes of self-deception.

62 is a lesser work than Hopscotch, then, less dense, less compelling, but an important and attractive book all the same. But we have to go back a number of years, to 1908, to reach the real masterpiece among the books under review: Machado de Assis’s Counselor Ayres’ Memorial, his last novel, published a few months before he died. The only work I know which is at all like this one is Jane Austen’s Persuasion, another late novel in which the author abandons fireworks in favor of the simplest kind of passion and elegance.

Memorial consists of the notebooks of the retired diplomat Ayres, the fictitious author of Machado’s Esau and Jacob (1904), for the years 1888 and 1889. We see the emancipation of the slaves in Brazil, greeted by Ayres with a sense of guilt—nothing will erase the stain from history—which holds him back from the general rejoicing. There is talk of a Republic, but the declaration occurred later in 1889, after these notes are closed, so that Machado gives us, in 1908, an ironic look back at the new Republic as if it were still an open book, a fresh, clear possibility still to come about. These political events have their relevance to the story, but they are talked about very discreetly, hinted at as a background of strife and injustice and subjection of men by men which corresponds in subtle ways to the private lives which occupy the foreground of the novel.

An old and extremely loving couple have never had children, but they take as their spiritual, borrowed son and daughter—as children “born of their affection,” as Ayres puts it—a young man whom they bring up and a young girl whose husband has died. The young man goes away to Portugal, becomes a Portuguese citizen, dabbles in politics. Then he returns, the false brother and sister fall in love, marry, and instead of settling in Brazil, go off to Portugal. The prodigal son has come back only to take away the faithful daughter, attracting her away from her fidelity both to her dead husband and to the old couple. All this is observed and deciphered by Ayres with sympathy and irony and a mild envy, as life fulfills what seems to be a law, leaving the old folks behind and the dead in their graves.

That’s all there is. A few faint and well-modulated echoes of Romeo and Juliet, of Dante, epigraphs suggesting flight with a lover over the sea to Lisbon, cruelly qualified by the fact that the flight of this book is away from people who need the fleeing ones desperately. Just as emancipation will mean bewilderment, and possibly a new enslavement, for many slaves, so the young couple’s freedom from the old couple enslaves the old couple in turn, ties them down to their memories. Machado is suggesting, delicately, that love may enslave as much as hatred or greed, that there is almost no event in life that is not to be greeted at best with a restrained, ambivalent joy, as Ayres greeted the news of the act of emancipation.

Machado’s tone, and his quiet, complicated humor, appear here as in Epitaph of a Small Winner (1881) and Dom Casmurro (1900), but much muted. The rest of Ayres’s notes will be published some day, we read, “if some day comes,” Ayres’s sister asks him for news of an auctioneer, and Ayres, bored by the request, tells her the man is dead. “He is probably still alive,” he thinks, “but he is sure to die some day.” Two or three days later he learns that the man has just died. He leaves coins in his pocket for his servant to steal, because he knows the servant could steal more if he chose. He enjoys malicious gossip if it’s funny.

He is the perfect, wry narrator for a story that would otherwise seem mawkish, the dry man we can’t accuse of excessive tenderness and who can therefore tell us this extraordinarily tender tale, offer us this ruined idyll, spoiled not by ugly sentiments or human failing but by simple passages of affections, leaving the old people lonely. The thought of incest, which would have kept real siblings unmarried but would also have kept at least the daughter in Brazil, faithful to her husband and her adopted parents, is nowhere hinted at in the novel, but it hangs constantly in the air, like the ghost of a transgression the young couple have committed: an effect that only a very great and very confident novelist could have achieved.

Dalton Trevisan is also a Brazilian, but the distance that separates him from Machado could hardly be greater, unless one thinks of Machado in certain sardonic, willful moods. Trevisan writes tight, dark short stories about jealousy, death, humiliation, panic, disease, loneliness. The selection is taken from seven books published by Trevisan between 1959 and 1969, and borrows its title from a set of stories concerning Nelsinho, a randy young man cropping up in various avatars, seducing shop girls, sleeping with his old teacher. He is the vampire of Curitiba because he preys on the women of the town and because he feels like a vampire doing it. He looks for his reflection in a window and thinks, “Since when does the image of Nosferatu cast a reflection?” He greets a girl with a smile and is careful not to show his black tooth, but then he makes the mistake of turning his bad ear to her, so that he can’t hear what she says.

This bleakly ludicrous note marks most of the stories. “The Perfect Crime” concerns a wife who is supposed to be killing her husband simply by grinding him down and going out a lot—only the man who offers this brilliant, angry diagnosis of someone else’s marriage goes home to a wife who seems to be working on him in the same way. “Thirty-Seven Nights of Passion” is about an unconsummated marriage, cancelled after the thirty-seventh night by the girl’s mother. The spare prose of this conclusion, and the sense of a great deal still to be said, are characteristic:

A month later they ran into each other by chance on the street. Maria left her mother and spoke to him quite naturally. He could barely light his cigarette, his hands were trembling so much.

Obviously there is a relation between writer and reader which is neither delegation nor parallelism but rage and provocation. One’s response to reading a sequence of Trevisan stories is a kind of anger at the perfection of the writer’s concealment, at his absolute moral invisibility, when we know he must be lurking somewhere behind his deadpan style. But this anger, presumably, is just what Trevisan wants from us.

I’m not sure what there is to say about Seven Voices except that it makes agreeable reading and goes on too long. Rita Guibert’s seven writers—Neruda, Borges, Asturias, Paz, Cortázar, García Márquez, Cabrera Infante—are very keen to talk and none of them can resist an epigram, or even an access of solemn rhetoric, when he feels one coming on. Liberty, Cabrera Infante tells us, in a context which suggests he is not joking, is the oxygen of history; and Neruda gravely reminds us that the most absolute of our duties is sincerity. “Octavio Paz, one last question: what are your plans for the future? Paz: To abolish it.”

Neruda is pompous, Borges is graceful and elusive (“that series of habits that’s known as Borges,” he says), Paz is wonderfully articulate and intelligent, but aimless, talking round and round a few familiar ideas. García Márquez tells funny stories and Cabrera Infante makes excruciating jokes which clearly delight him: “Emily Brontë may not be the Victoria Regina of the nineteenth-century novel, but she is something better: its Vagina Rectoria.” I think of the work that goes into a joke like that and shudder. Cabrera Infante is also full of anecdotes about Castro and Guevara and paranoia as a political system, but ends up, like many a man on the run from an ideology, as the ideological defender of the middle of the road: “I believe that all ideologies are reactionary…communism is merely the poor man’s fascism.”

On the whole, everyone talks too well here, and what would be a pleasure to listen to becomes dull and self-conscious on paper. This is not Rita Guibert’s fault, since she obviously conducted the interviews with great tact and skill. But there it is. Or rather, there they are: seven garrulous men anxious to tell the world where it’s at, writers on their day off, motors idling, tongues wagging.

This Issue

April 19, 1973