No American black leader I know of carries on the tradition of Booker T. Washington. This does not mean, of course, that echoes of his ideas are not to be heard here and there. Racial separation, for example, remains a major aim of certain groups within the black movement, although the argument made for it in recent times has been aggressive and demanding where Washington’s was essentially submissive. But no black leader would dare now to endorse Washington’s policies of acquiescence in segregation and disfranchisement; emphasis on industrial training in preference to higher education and equal opportunity; rejection of racial and social protest in favor of self-help, business enterprise, and political accommodation. The changes since 1915, when Washington died, or since the first three or four years of the century, when he was at the height of his influence, have made his program anathema for blacks.

But this is far from true for a large constituency of whites. One senses in this country today an attitude toward continued black progress that recalls, however faintly, the late nineteenth century in America when—after Reconstruction had been betrayed and the federal government had withdrawn its protection of black rights in the South—black progress was dramatically reversed, and when Booker T. Washington, one of the few black men who prospered under these conditions, was rising to a position of leadership. As W.E.B. DuBois observed in 1903:

Easily the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington. It began at a time when war memories and ideals were rapidly passing; a day of astonishing commercial development was dawning…. Mr. Washington came with a single definite programme, at a psychological moment when the nation was a little ashamed of having bestowed so much sentiment on Negroes, and was concentrating its energies on Dollars. [Italics added.]

What one senses today springs from the policy of silence or indifference, or worse, which the Nixon Administration appears to have adopted toward some of the most important racial and social reforms enacted between 1960 and 1968—reforms which had the effect or at least held out the promise of restoring many of the rights and freedoms revoked between the 1870s and the 1890s. Perhaps this new policy was most charitably named by the former cabinet member who counseled Mr. Nixon that “the time has come when the issue of race could benefit from a period of benign neglect.” Mr. Moynihan’s sentiments (like those of his colleagues who speak today as if their former broad support of the politics of racial equality is a liberal indiscretion they would like as soon as possible to forget) may well be similar to those DuBois remarked upon earlier when he said that “the nation was a little ashamed.” More recently, the policy of neglect appears to have been extended to poverty—which is to say that it now applies to the issue of race both politically and economically (though one realizes, of course, that there are more whites below the federal poverty level than there are blacks).

So this seems a good moment to reconsider Booker T. Washington. There is no better source to consult than Louis R. Harlan’s biography and the first two (of a projected fifteen) volumes of the Washington Papers, which he is editing. The biography, which follows Washington “from birth to the plateau of his power and influence in 1901,” is a major contribution to black American history, drawing more heavily on Washington’s papers than any other study of its kind, and as objective in its treatment of Washington as one can reasonably expect. One might complain that Harlan writes rather flatly, if clearly, and that Washington does not emerge vividly from Harlan’s careful work on the documents, but his book is nevertheless the most impressive study we have of Washington and his period.

It may be true, as DuBois said, that the most striking thing in black history of the late nineteenth century was the ascendancy of Washington. But I think we would do well to attend to Washington’s ideas and the sources of those ideas—without which he would have been quite unable to appeal to those who made his ascendancy possible. It is customary in considering Washington to pay the most attention to his skill as a political operator, at changing masks, and his mastery of the art of saying one thing to white Southern conservatives (what he knew they wanted to hear) while appearing to be saying something different to his own people. Harlan himself seems to look at Washington in this way. He writes:

Power was his game, and he used ideas simply as instruments to gain power…. The complexity of…Washington’s personality probably had its origin in being black in white America. He was forced from childhood to deceive, to simulate, to wear the mask. With each subgroup of blacks or whites that he confronted, he learned to play a different role, wear a different mask.

All of which supports the conclusion that Washington’s views on racial and other public issues were determined chiefly by habits of deception and by what he conceived to be expedient political strategy.

Advertisement

Some of this may be true. But when one looks closely at Washington’s reputation, it seems to rest most solidly not upon his record as a political dissembler but upon the peculiar ideas with which he sought to describe the black situation and to prescribe how blacks ought to deal with it. No other leader in black history has been so closely identified with doctrines that weakened his people’s aspiration for freedom, that urged them instead to make a virtue of their disadvantage. They were not the doctrines of an oppressed people, but of paternalistic Southern white racism—the views of men who were nostalgic for slavery, and who, as Frederick Douglass once said, “shrink back in horror from contact with the Negro as a man and gentleman, but like him very well as a barber, waiter, coachman and cook.”

How did a black leader come by such ideas? The influences upon a man’s outlook may be complex, to be sure, and, as Harlan suggests, sources in Washington’s childhood are not to be overlooked. Yet I think much about Washington is explained by his attachment to General Samuel C. Armstrong, the founder and headmaster of Hampton Institute, where Washington, a virtually penniless sixteen-year-old ex-slave, who regarded himself as an unformed piece of clay, journeyed in 1872 for an education. Several years later, in his autobiography, Up From Slavery, Washington wrote that Armstrong “made the greatest and most lasting impression upon me,” and described him as “the noblest, rarest human being that it has ever been my privilege to meet…a perfect man…there was something about him that was superhuman.”

The object of all this affection was a man who, in comparing blacks with Polynesians, once said, “Of both it is true that not mere ignorance, but deficiency of character is the chief difficulty…. Especially in the weak tropical races, idleness, like ignorance, breeds vice.” On another occasion, he observed that “the differentia of races goes deeper than skin,” and that a black man was a primitive whose “mechanical faculty works quickly and outstrips his understanding.” To him—and to Hampton, which taught his philosophy—industrial training was “a quasi religious principle, for the temporal salvation of the Negro race.”

When Armstrong tried to visualize the day when blacks would be ready for higher education, it seemed so far in the future as to render the effort useless. He made a point of counseling his young black charges at Hampton to avoid politics, labor unions, and such professions as the law. “The founding of Hampton,” Harlan writes, “had grown out of the General’s disillusionment with the rainbow dreams of Reconstruction…. When the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was passed…the Southern Workman [Hampton’s newspaper] pleaded with black people ‘to raise no needless and ill-considered issue under the present law,’ and to use integrated facilities only when none were provided for blacks separately.” No wonder the militant black bishop Henry M. Turner found, on a visit to the school in 1878, that it taught “Negro inferiority.”

All of this—as Harlan writes, commenting upon Washington’s graduation in 1875—“wrought such a transformation of his life and thought that he might be said to have been born again.” Harlan goes on:

In General…Armstrong he found the white father figure he had perhaps unconsciously been searching for…. Washington’s years at Hampton became the central shaping experience of his life, and General Armstrong’s social philosophy and example became the beacon that guided Washington throughout the rest of his life….

Washington later referred to him as “more than a father” and as “the most perfect specimen of man, physically, mentally and spiritually” that he had ever seen…. Washington came to model his career, his school, his social outlook, and the very cut of his clothes after Armstrong’s example.

In fact, the test of almost everything Washington said and did after leaving Hampton was whether it was the sort of thing General Armstrong would approve of. In 1876, while Washington was teaching for a short time at Hampton, the Hayes-Tilden Compromise ended Reconstruction, in effect abolishing the franchise for large numbers of blacks and throwing their elected representatives out of office. Washington seems to have been no more drawn to “the rainbow dreams of Reconstruction” than Armstrong himself, and, like Armstrong, he would have “openly endorsed the compromises by which Reconstruction ended.” Tuskegee Institute, which he founded in 1881, was organized along the same lines and upon the same principles as Hampton. In 1883, when the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, Washington took it complacently.

Advertisement

Harlan believes that after Armstrong’s death, in 1893, a significant change took place in Washington:

In a sense, the death of the fatherly Armstrong…was for Washington a liberation. He continued throughout his life to venerate Armstrong and to endorse his educational philosophy, but in matters of general racial policy it was increasingly clear that if he was to be a black leader he must pursue goals and use methods that never would have been conceived or approved by Armstrong. For financial aid, he would have to move on from the philanthropy of the New England Sunday school to that of the temples of business…. He would have to be more of a “race man,” more a spokesman for black people….

This seems unconvincing. Washington had been expressing his accommodationist ideas for some time before; but it was not until 1895, two years after Armstrong’s death, that he found a platform for them, in his speech before the Atlanta Exposition. What he said then surely did not make him “more a spokesman for black people.” He sometimes gave covert support to blacks who engaged in skirmishes with the Southern system; but the secrecy of his assistance—or whatever considerations required him to act in secret—is not the behavior of a man who has been converted into a spokesman for his people.

Washington’s turning to “the temples of business” for financial support would scarcely have displeased Armstrong, so long as the proceeds promoted the work at Tuskegee, which both men considered to be of the utmost importance. Armstrong would have insisted on making two assumptions, neither of which Washington abandoned: blacks were not, at the expense of industrial education, to be trained in the arts, politics, or the professions; and efforts in their behalf had to be conciliatory and accommodationist, not militant or radical or protesting. Thus, in all things that were essential to keeping blacks submissive in Southern society, Washington remained a faithful pupil of Armstrong and Hampton Institute.

We must remember that Washington gave his speech soon after Frederick Douglass died, one year before the Supreme Court endorsed the separate but equal doctrine, and at the time when the political fortunes of blacks were steadily worsening and Jim Crow laws were being passed all over the South. He became the most important black leader in the US by reassuring the white South that blacks should begin at the bottom, by pledging that blacks were ready to serve the South in laboring and other nonintellectual jobs, by appealing to his white listeners to cast down their buckets “among the eight million Negroes whose habits you know, whose fidelity and love you have tested….” Before he sat down, he had made it clear that the principle of black political rights was not in question: “The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly….” Even Harlan, a biographer who does not easily criticize his subject, is unable to resist the conclusion that

Booker T. Washington’s racial Compromise of 1895, as August Meier notes, “expressed Negro accommodation to the social conditions implicit in the earlier Compromise of 1877.” As often in his career, Washington’s rise coincided with a setback of his race.

It is not even correct to say that he “expressed Negro accommodation.” “Pledged” or “promised” may be a better term, for, in a sense, what Washington was expressing were his own desires and those of the white South. He was no more representing the unarticulated wishes of the black masses than those masses had chosen him as their spokesman and leader. I think Frederick Douglass more accurately expressed their genuine aspirations when he opposed white supremacist codes on the grounds that they were “calculated to repress [the Negro’s] manly ambition, his energies, and make him a dejected and spiritless man.” As Harlan notes,

…blacks had virtually nothing to do with making Washington a black leader…. Southern conservatives…chose Booker Washington rather than any one of a dozen Negroes at least as prominent, because they regarded him as a “safe” Negro counselor, one whom they wanted to encourage…. The Southerners sought a black man who would symbolize that Reconstruction was over, and one they could consider an ally against not only the old Yankee enemy but the Southern Populist and labor organizer. They wanted a black spokesman who could reassure them against the renewal of black competition and racial strife. And Northern whites as well were in search of a black leader who could give them a rest from the eternal race problem.

Considering how much of his reputation rests upon the opposition he led against Washington’s compromise policies, it is interesting to note that DuBois was at first not at all troubled by what Washington had said in Atlanta. In fact, he wrote Washington to “heartily congratulate you upon your phenomenal success at Atlanta—it was a word fitly spoken.” Which seems a surprising statement, since Washington had just dismissed the principle of black rights. DuBois was silent then, Harlan explains, because both men “were not as far apart as they later believed themselves to be.” (Apparently, Harlan has doubts that they were so far apart even later on.) Anyway, Washington’s biographer goes on to name a number of projects on which Washington and DuBois held somewhat harmonious views around the turn of the century. At one point Washington was even considering DuBois for a post at Tuskegee.

Why, then, was DuBois ready by 1903 to come out against Washington? As he explained later,

Organized opposition…arose first quite naturally. Not only did presidents of the United States consult Booker Washington, but governors and congressmen; philanthropists conferred with him, scholars wrote to him…. After a time almost no Negro institution could collect funds without the recommendation or acquiescence of Mr. Washington. Few political appointments were made anywhere in the United States without his consent. Even the careers of rising young colored men were very often determined by his advice and certainly his opposition was fatal.1

He also explained on another occasion that

I was increasingly uncomfortable under the statements of Mr. Washington’s position: his depreciation of the value of the vote; his evident dislike of Negro colleges; and his general attitude which seemed to place the onus of blame for the status of Negroes upon Negroes themselves rather than upon the whites.2

In any event, DuBois felt by 1903 that the time had come for him to speak out, and what he said, in one of his best-known essays,3 remains the definitive contemporary attack on the doctrine Washington expounded in 1895. DuBois wrote:

This “Atlanta Compromise” is by all odds the most notable thing in Mr. Washington’s career…. So far as [he] preaches Thrift, Patience, and Industrial Training for the masses, we must hold up his hands and strive with him…. But so far as Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice, North or South, does not rightly value the privileges and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds—so far as he, the South, or the Nation does this—we must increasingly and firmly oppose him. By every civilized and peaceful method we must strive for the rights which the world accords men….

Would blacks in the South have been better served by more militant leaders like Douglass and DuBois than by those like Booker T. Washington? It is difficult to speak with any authority today. Both policies involved enormous risks, and who can know now what those blacks who lived at the time were prepared to suffer in the name of one policy or another? But the intense anti-black feeling that flared up after Reconstruction and continued to the end of the century, and the absence of federal protection of black rights and black lives, do not suggest that a militant protest leadership would have been capable of making any important gains whatever. A fruitless struggle might still have provoked a far more violent and bloody reaction from the white South than that which actually occurred, in spite of Washington’s accommodation.

Further, since a protesting or self-assertive leadership would not have emphasized, as Washington did (with some success), the need for industrial education—and would have lacked the philanthropic support to advance the goals of higher education—its practical accomplishments might have been nil. (This ignores the possibility, of course, that a militant protest movement might, even under such repressive conditions, have aroused the conscience of many in the North, as happened in the 1960s. But that is doubtful. America was a very different country then.)

What one can say with some certainty is this: the one lasting contribution of a more aggressive leadership would have been its absolute refusal to surrender, as Washington did, the political cause and the human rights of the people they presumed to lead. Few contributions, under the circumstances, would have been more valuable.

For one must also see that almost every important achievement of Washington’s leadership—with the exception of the work at Tuskegee, which still goes on—has been diminished, partly by the influx of skilled labor from Europe, and partly by the fact that black workers failed first to seek and later to obtain the protection of the organized trade union movement in the South. They failed to seek it because they had been counseled by Washington against forming trade unions. And when, in spite of Washington’s teachings, it became clear that they needed the protection of the trade union movement, they failed to get it because by then the movement had become solidly racist and exclusionist—consenting (when finally it did so) to organize blacks only in second-class and segregated locals. But black workers were by then powerless to do anything about it. By abandoning the quest for political rights, their leaders were also allowing Jim Crow unions to be organized. Consequently, there were no institutions among blacks that could press their full and equal claims upon the labor movement. It was one of the most striking and disastrous paradoxes of Washington’s policies.

As it turned out, it was the more intransigent leadership of men like A. Philip Randolph, who was himself rooted in the tradition of Douglass and DuBois, that, regrouping a few years before Washington’s death, led the long uphill struggle to the 1960s, when many of the rights revoked after Reconstruction were restored. What is happening to those gains now? The recent policies of neglect of blacks—“benign” or not—are all too reminiscent of the post-Reconstruction mood in which Booker T. Washington flourished, with excruciating consequences for American life.

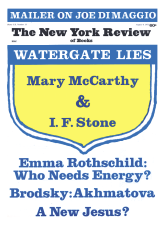

This Issue

August 9, 1973

-

1

“My Early Relations with Booker T. Washington,” in Booker T. Washington, edited by E. L. Thornbrough (PrenticeHall, 1969), p. 127. Reprinted from Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept, by W. E. B. DuBois (Harcourt Brace & World, 1940), pp. 70-80.

↩ -

2

The Autobiography of W. E. B. DuBois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century (International Publishers, 1968), p.244.

↩ -

3

“Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others,” in The Souls of Black Folk (McClurg, 1903), pp. 42-54.

↩