The failure of a second work is, I think, more damaging to a writer than failure ever will be again. The success of the first work—in my case, The Children’s Hour, which went into the sensational because I was young and unheard of—then seems an accident. Maybe the wrong people liked it, maybe you played good tricks, just maybe you are no good. The praise is usually out of bounds: the photographs, interviews, “appearances,” party invitations are so swift and dazzling that you go into the second work with confidence you will never have again if you have any sense. And failure in the theater is more public, more brilliant, more unreal than in any other field.

Days to Come was written in Princeton, New Jersey. Dashiell Hammett, who never wanted much to live in New York, had rented the house of a rich professor who was a Napoleon expert. Its over-formal Directoire furniture was filled each night with students who liked Hammett, but liked even better the free alcohol and the odd corners where they could sleep and bring their friends. That makes it sound like now, when students are often interesting, but it wasn’t: they were a dull generation, but Dash never much examined the people to whom he was talking if he was drunk enough to talk at all.

Even now the pains I had on the opening night of Days to Come puzzle me. Good theater jokes are almost always based on survived disasters and there were so many that night that they should, in time, have passed into comedy: the carefully rehearsed light cues worked as if they were meant for another play; the props, not too complicated, showed up where nobody had ever seen them before and broke, or didn’t break, with the malice of animate beings; good actors knew by the first twenty minutes that they had lost the audience and thus became bad actors; the audience, maybe friendly when it came in, was soon restless and uncomfortable. The air of a theater is unmistakable: things go well or they do not. They did not. Standing in the back of the side aisle, I vomited without knowing it was going to happen and went home to change my clothes. I wanted, of course, to go to bed and stay there, but I was young enough to worry about cowardice and so I got back in time to see William Randolph Hearst lead his six guests out of the theater, in the middle of the second act, talking very loudly as he came up the aisle.

It is hard for me to believe, these many years later—I read the play again last year for the first time since the production and liked most of it—in the guilt I felt for the failure of Days to Come. The threads of those threads have lasted to this day. Guilt is often an excuse for not thinking and maybe that’s what happened to me. In any case, it was to be two years before I could write another play, The Little Foxes, and when I did get to it I was so scared that I wrote it nine times.

Ten of the twelve plays I have written are connected to Hammett—he was in the army in the Aleutian Islands for one of them, and he was dead when I wrote the last—but The Little Foxes was the one that was most dependent on him. We were living together in the same house, he was not doing any work of his own but, after his death, when much became clear to me that had not been before, I knew that he was working so hard for me because Days to Come had scared me and scared him for my future.

The Little Foxes was the most difficult play I ever wrote. I was clumsy in the first drafts, putting in and taking out characters, ornamenting, decorating, growing more and more weary as the versions of the scenes and then acts and then three whole plays had to be thrown away. Some of the trouble came because it had a distant connection to my mother’s family and everything that I had heard or seen or imagined had formed a giant, tangled time-jungle in which I could find no space to walk without tripping over old roots, hearing old voices speak about histories made long before my day.

In the first three versions of the play, because it had been true in life, Horace Giddens had syphilis. When Regina, his wife, who had long refused him her bed, found out about it she put fresh paint on a miserable building that had once been used as slave quarters and kept him there for the rest of his life because, she said, he might infect his children. I had been told that the real Regina would speak with outrage of her betrayal by a man she had never liked and then would burst out laughing at what she said. On the day he died, she dropped the moral complaints forever and went horseback riding during his funeral. All that seemed fine for the play. But it wasn’t: life had been too big, too muddled for writing. So the syphilis became heart trouble, I cut out the slave cabin and the long explanations of Regina and Horace’s early life together.

Advertisement

I was on the eighth version of the play before Hammett gave a nod of approval and said he thought maybe everything would be okay if only I’d cut out the “blackamoor chit-chat.” I knew that the toughness of his criticism, the coldness of his praise, gave him a certain pleasure. But even then I, who am not a good-tempered woman, admired his refusal with me, or with anybody else, to decorate or apologize or placate. It came from the most carefully guarded honesty I have ever known, as if one lie would muck up his world. If the honesty was mixed with harshness, I didn’t much care, it didn’t seem to me my business. The desire to take an occasional swipe is there in most of us, but most of us have no reason for it, it is as aimless as the pleasure in a piece of candy. When it is controlled by sense and balance, it is still not pretty, but it is not dangerous and often it is useful. It was useful to me and I knew it.

The casting of the play was difficult. We offered it to Ina Claire and to Judith Anderson. Each had a pleasant reason for refusing: each meant that the part was unsympathetic, a popular fear for actresses before that concept became outmoded. Herman Shumlin, the producer-director, asked me what I thought of Tallulah Bankhead, but I had never seen her here or in her famous English days. She had returned to New York by 1939, had done a couple of flops, and was married to a nice, silly, handsome actor called John Emery.

She was living in the same hotel I was, but I had fallen asleep by the time Herman rang my bell after six hours spent upstairs with Tallulah on their first meeting. He said he had a headache, was worn out by Miss Bankhead’s vitality, but he thought she would do fine for us if he could, in the future, avoid the kind of scene he had just come from: she had been “wild” about the play, wild enough to insist the consultation take place while she was in bed with John Emery and a bottle. Shumlin said he didn’t think Emery liked that much, but he was certain that poor Emery was unprepared for Tallulah’s saying to Herman as he rose to go, “Wait a minute, darling, just wait a minute. I have something to show you.” She threw aside the sheets, pointed down at the naked, miserable Emery, and said, “Just tell me, darling, if you’ve ever seen a prick that big.” I don’t know what Herman said but it must have been pleasant because there was no fight that night, nothing to predict what was to come.

I still have a diary entry, written a few days later, asking myself whether talk about the size of the male organ isn’t a homosexual preoccupation: if things aren’t too bad in other ways I doubt if any woman cares very much. Almost certainly Tallulah didn’t care about the size or the function: it was the stylish, épater palaver of her day.

It is a mark of many famous people that they cannot part with their brightest hour: what worked once must always work. Tallulah had been the Twenties’ most daring girl, but what had been dashing, even brave, had become, by 1939, shrill and tiring. The lives of the special darlings in the world of art and society had been made old-fashioned by the economic miseries of those who had never been darlings. Nothing is displaced on a single day and much of the Twenties was left over during the Depression, but the train had made a sharp historical swing and the fashionable folk, their life and customs, had become loud and tacky.

Tallulah, in the first months of the play, gave a fine performance, had a well-deserved triumph. It was sad to watch it all decline into shrill high-jinks on the stage and in life. Long before her death, beginning with my play, I think, she threw the talent around to amuse the campy boys who came each opening night to watch her vindicate their view of women. I didn’t clearly understand all that when I first met her, but I knew that while there was probably not more than five years’ difference in our ages, and a bond in our Southern background—her family came from an Alabama town close to my mother’s—we were a generation apart.

Advertisement

I knew many of the virtues and the mistakes of The Little Foxes before the play opened, but I wanted, I needed an interesting critical mind to tell what I had done beyond the limited amount I could see for myself. The high praise and the few reservations seemed to me stale stuff and I think were one of the reasons why the great success of the play sent me into a wasteful, ridiculous depression. I sat drinking for months after the play opened trying to figure out what I had wanted to say and why some of it got lost.

I grew restless, sickish, digging around the random memories that had been the conscious or semiconscious material for the play. I had meant to half mock my own youthful high-class innocence in Alexandra, the young girl in the play; I had meant people to smile at, and to sympathize with, the sad, weak Birdie, certainly I had not meant them to cry: I had meant the audience to recognize some part of themselves in the money-dominated Hubbards. I had not meant people to think of them as villains to whom they had no connection.

I belonged, on my mother’s side, to a banking, store-keeping family from Alabama, and Sunday dinners were large, with four sisters and three brothers of my grandmother’s generation, their children, and a few cousins of my age. These dinners were long, with high-spirited talk and laughter from the older people of who did what to whom, what good nigger had consented to 30 percent interest on his cotton crop and what bad nigger had made a timid protest, what new white partner had been outwitted, what benefits the year had brought from the Southern business interests they had left behind for the Northern profits they had had sense enough to move toward.

When I was fourteen, in one of my many religious periods, I yelled across that Sunday’s dinner table at my great aunt, “You have a spatulate face made to dig in the mud for money. May God forgive you.” My aunt rose, came around the table, and slapped me with her napkin. I said, “Some day I’ll pay you back unless the dear God helps me conquer the evil spirit of revenge,” and ran from the room as my gentle mother started to cry. But, later that night, she knocked on my locked door and said that if I came out I could have a squab for dinner. My father was out of New York but, evidently informed of the drama by my mother, wrote to me saying that he hoped I had the sense not to revenge myself until I was as tall and as heavy as my great aunt.

A few years after I had stopped being pleased with the word spatulate, a change occurred for which even now I have no explanation. I began to think that greed and the cheating that is its usual companion were comic as well as evil, and I began to like the family dinners with the talk of who did what to whom. I particularly looked forward to the biannual dinner when the sisters and brothers assembled to draw lots for “the diamond” that had been left, almost thirty years before, in my great-grandmother’s estate. Sometimes they would use the length of a strip of paper to designate the winner, sometimes the flip of a coin, and once I was allowed to choose a number up to eight and the correct guesser was to get the diamond.

But nobody, so far as I know, ever did get it. No sooner was the winner declared than one loser would sulk, and, by prearrangement, another would console the sulker and a third would start the real event of the afternoon: an open charge of cheating. The paper, the coin, my number, all had been fixed or tampered with. That was wild and funny. Funnier because my mother’s generation would sit white-faced, sometimes tearful, appalled at what was happening, all of them envying the vigor of their parents, half-knowing that they were broken spirits who wished the world was nicer, but who were still so anxious to inherit the money that they made no protest.

I was about eighteen when my Great Uncle Jake took the dinner hours to describe how he and a new partner had bought a street of slum houses in downtown New York. He, Jake, during a lunch break in the signing of the partnership, removed all the toilet seats from the buildings and sold them for fifty dollars. But, asked my cousin, what will the poor people who live there do without toilet seats? “Let us,” said Jake, “approach your question in a practical manner. I ask you to accompany me now to the bathroom where I will explode my bowels in the manner of the impoverished and you will see for yourself how it is done.” As he reached for her hand to lead her to the exhibition, my constantly ailing cousin began to cry in high, long sounds. Her mother said to her, “Go along immediately with your Uncle Jake. You are being disrespectful to him.”

By the time I came to The Little Foxes, I still liked all that, but my anger with what the Hubbards had done to America came out another way.

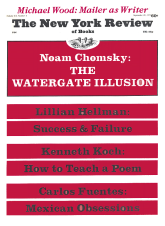

This Issue

September 20, 1973