Little boy kneels at the foot of the bed,

Droops on the little hands little gold head.

Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares!

Christopher Robin is saying his prayers.

Uppermost in Christopher Robin’s prayers, if we are to believe A.A. Milne, were Mummie, Daddy, and Nanny—not, however, in James Morris’s. “Please, God,” went this little boy’s nightly orison, “let me be a girl. Amen.” And he made the same prayer whenever he “saw a shooting star, won a wishbone contest, or visited a Blarney well.” His persistence was rewarded, but not for forty years. In the summer of 1972, thanks to the intervention of a Moroccan surgeon, this popular British author—ex-cavalry officer, foreign correspondent, mountain climber, father of four—became Jan: a sister-in-law to his wife, “an adoring if interfering” Auntie Jan to his children.

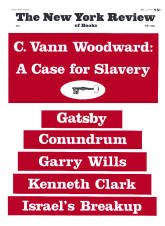

Now that her ordeal is over and she has settled down in Bath, Jan Morris has decided to tell all, well not quite all, about “the most fascinating experience that ever befell a human being.” Sure enough this award-winning travel writer squeezes maximum mileage out of the most sensational and perilous trip he/she ever took, the trip from one sex to another. And sure enough, Conundrum lives up to its peculiar subject, disarming one with Welsh charm one moment, disconcerting one with genteel exhibitionism the next. For a change compulsive writing—Conundrum has to be seen as the last act, or rather the last curtain call, in Jan’s sex change—makes for compulsive reading. Yet it is also an irritating book: coyly reticent where it should be frank, whimsical where it should be scientific, embarrassing where it aims to be touching.

The trouble with confessional writers is that their confessions are apt to become specious advertisements for themselves. Euphemisms can be made to excuse or enhance all manner of errors. Take the recent Portrait of a Marriage. Vita Sackville-West beat her breasts flat describing an entanglement with another woman, but she never admitted to being a lesbian; she called it having “a dual personality.” The same with the author of Conundrum. James/Jan suffered from a decidedly more dual personality than Vita, but he/she finds a totally different pretext for her maladjustment: changing sex was a spiritual act—“I equate it with the idea of soul.”

Yes, Conundrum aims at being an inspirational book, especially in its piety where women are concerned. With all the fanaticism of a convert, Jan insists on seeing women as frail, virginal beings (woman’s “frailty is her strength, her inferiority is her privilege”) divinely entitled to both pedestal and halo. These misconceptions go back to the authoress’s boyhood: “A virginal ideal was fostered in me by my years at [school], a sense of sacrament and fragility, and this I came slowly to identify as femaleness—’eternal womanhood,’ which, as Goethe says…’leads us above.’ ” Elsewhere we read how the boy identified with nuns, with the Virgin Mary. He envied the Virgin Birth, and came to see his transsexual voyage as a sacramental or visionary quest. “It has assumed for me a quality of epic, its purpose unyielding, its conclusion inevitable.”

These ideas carry as much conviction as a transvestite’s falsies. Granted, they serve somewhat the same purpose in that they were invaluable props, when James was easing himself into a female role, but they will not make Jan as welcome a recruit to “the monstrous regiment,” as she evidently hopes. And they will surely be anathema to Women’s Lib—unfortunate because Jan is deluded enough to see herself as a Female Chauvinist. “It still seems to me only common sense to wish to be a woman rather than a man—or if not common sense, at least good taste.” Or again, as reported by The New York Times: “I like being a woman, but I mean a woman. I like having my suitcase carried…. I would have been happiest being someone’s second in command. Lieutenant to a really great man.”*

The sex change seems to have amplified certain maudlin tendencies which were formerly contained within James’s dashing masculinity. For on the face of things Morris could not have been a more stolid type. Part Welsh, part Quaker, he had a conventional middle-class upbringing: Christ Church choir school, a minor public school (Lancing), Oxford, and five years in a cavalry regiment. True, he had desultory affairs with men, but Jan claims a bit sententiously that he found homosexuality childish and sterile. In any case he craved to have children, and so at the age of twenty-two he married an understanding girl who sympathized with his problem. “It was a marriage that had no right to work, yet it worked like a dream…. I hid nothing from Elizabeth…I told her that though each year my every instinct seemed to become more feminine, my entombment within the male physique more terrible to me, still the mechanism of my body was complete and functional, and for what it is worth was hers.”

Advertisement

James confesses that he really wanted to be a mother—“perhaps my preoccupation with virgin birth was only a recognition that I could never be one.” Faute de mieux he became a father, siring five children, one of whom died in infancy. Let me quote the description of this unhappy event, because it pinpoints the way Jan embarrasses her readers when she strives to touch them. And note the sound effects—a recurrent device of this writer.

I felt she would surely come back to us, if not in one guise, then in another—and she very soon did, leaving us sadly as Virginia, returning as Susan, merry as a dancing star.

…we knew she was very near death. Elizabeth and I lay sleepless in our room overlooking the garden…. Towards midnight a nightingale began to sing…. I had never heard an English nightingale before, and it was like hearing for the first time a voice from the empyrean. All night long it trilled and soared in the moonlight, infinitely sad, infinitely beautiful…. We lay there through it all,…the tears running silently down our cheeks, and the bird sang on, part elegy, part comfort, part farewell, until the moon failed and we fell hand in hand into sleep.

In the morning the child had gone.

Jan must take most of the blame for this mawkish stuff, for at his best James was an excellent journalist. How else could he have held down a top job as correspondent for the (London) Times and subsequently the Manchester Guardian? How else could he have done justice to one of the biggest journalistic breaks in history: the Mount Everest story? Conundrum describes how Morris accompanied the 1953 expedition to 22,000 feet, and organized his means of communication so ingeniously that the Times scooped the world with the news of Hillary’s and Tenzing’s triumph. Jan’s bragging description of James’s heroic role in this exploit is worth quoting:

How brilliant I felt, as with a couple of Sherpa porters I bounded down the glacial moraine towards the green below! I was brilliant with the success of my friends on the mountain, I was brilliant with my knowledge of the event, brilliant with muscular tautness, brilliant with conceit, brilliant with awareness of the subterfuge, amounting very nearly to dishonesty, by which I hoped to have deceived my competitors and scooped the world. …my news had reached London providentially on the eve of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, I felt as though I had been crowned myself.

I never mind the swagger of young men. It is their right to swank, and I know the sensation!

It is disconcerting to watch the dashing fellow who bounds down the moraine turn in the space of a paragraph into a little woman who does not mind a bit of swagger, and elsewhere enjoys “a touch of swank”—Dr. Jekyll into Mrs. Hyde.

Everest was the high point of James’s career as a journalist. By putting his masculinity to the test the mountain deepened his sense of duality. Back home James had to fight an increasing sense of isolation from the world: he began to suffer from migraines, distortions of vision and speech “preceded by periods of terrific elation, as though I had been injected with some gloriously stimulating drug.” This state was not helped by his journalistic assignments which involved “little but misery or chicanery, as I flew from war to rebellion, famine to earthquake, diplomatic squabble to political trial.” And as he admits, his condition even had stylistic repercussions: “the elaboration of my prose…which all too often declined into rhetoric, but did have its moments of splendor, owed much to what I was.”

More and more James sublimated his sexual appetite such as it was (anyone who really enjoyed sex would hardly swap a set of functioning organs for what amounts to a very Rube Goldberg contrivance) into sensual feelings for inanimate objects: “buildings, landscapes, pictures, wines, and certain sorts of confectionery…whole cities are mine because I have loved them so. So are pictures scattered through the art galleries of the world. If you love something hotly enough, consciously with care, it becomes yours by symbiosis irrevocably.” Arabia, Venice, South Africa are some of the places that James wrote about with increasing success, and, alas, rapture. Meanwhile, what about Elizabeth? Was “the incomparable gift of children” really enough to console her for James’s infidelities with plates of mille feuilles or the Doges Palace, not to speak of the hormones he had begun to take?

Advertisement

As James traveled round the world, sating his lust for cities in the purple of his prose, events were being forecast for him “arcanely” (a very Morris word):

A Xosa wise woman, telling my future in her dark hut of the Transkei, had assured me long before that I would one day be a woman too; a reader of mine in Stockholm had repeatedly warned me that the King of Sweden was changing my sex by invisible rays. As you know, I had myself long seen in my quest some veiled spiritual purpose, as though I was pursuing a Grail or grasping Oneness. There was, however, nothing mystic about the substances I now employed to achieve my ends…. The pills I now took three times a day…were made in Canada from the urine of pregnant mares.

…[These] turned me gradually from a person who looked like a healthy male of orthodox sexual tendencies…into something perilously close to a hermaphrodite, apparently neither of one sex nor the other, and more or less ageless. I was assured that this was a reversible process, and that if…I decided to go no further, I might gradually revert to the male again; but of course the more frankly feminine I became the happier I was, object of curiosity though I became,…and embarrassment I fear, though they never dreamt of showing it, to Elizabeth and the children.

James says that his “small breasts blossomed like blushes,” and his rough male hide took on a nubile girlish glow; he turned into “a chimera, half male, half female, an object of wonder even to myself.” These physical changes were accompanied by odd feelings of levitation, the emergence of quivering new responses and lightheadedness, as when Jan found herself “talking to the garden flowers, wishing them a Happy Easter, or thanking them for the fine show they made.” ” ‘Was the whole process affecting her mind a little?’ ” asked an editor who had worked on an early draft of Conundrum. “But no, I had been talking to my typewriter for years.”

Meanwhile James lived part of the time with his wife and family as a man. Jan, however, took a small house at Oxford, where she could occasionally try out life as a woman. At the Traveller’s Club James had perforce to be known as a man—at least to his face—but the porter at another London club to which he belonged welcomed him as Madam. The pages which describe this in-between phase of James’s life are the best part of the book. The earnestness is at last relieved by glints of sense and humor, especially when he evokes some of the confusions resulting from his androgynous state, for instance when James visited his son at Eton, and a matron mistook the queer-looking father for one of the boys (shades of Vice Versa), or when a South African restaurant made him wear a tie at lunch, but would not let her wear pants at dinner.

In Mexico…a deputation of housemaids came to my door one day. “Please tell us,” they said, “whether you are a lady or a gentleman.” I whipped up my shirt to show my bosom, and they gave me a bunch of flowers when I left. “Are you a man or a woman?” asked the Fijian taxi-driver as he drove me from the airport. “I am a respectable, rich, middle-aged English widow,” I replied. “Good,” he said, “just what I want,” and put his hand upon my knee.

Americans assumed him to be female and cheered him up with small attentions:

Englishmen of the educated classes found the ambiguity in itself beguiling…. Frenchmen were curious…. Italians…simply stared boorishly…. Greeks were vastly entertained. Arabs asked me to go for walks with them. Scots looked shocked. Germans looked worried. Japanese did not notice.

Mare’s urine effectively feminized James, but his body still produced “male hormones in rearguard desperation.” He therefore decided to consult a surgeon. Thanks to the persuasion of an enlightened endocrinologist, Dr. Harry Benjamin of New York City, sex change by surgery was no longer considered “a cross between a racket, an obscenity, and a very expensive placebo,” but the rational solution to most transsexual problems.

England, where James began to make the necessary inquiries, had followed the US in accepting transsexuals. Conundrum does not tell us, but a typically British hierarchy has grown up in the no man’s land between the sexes. At the top are the grandes dames who at considerable pain and cost have undergone a series of complex operations involving the removal of penis and testicles and the installation of a vagina cobbled out of the leftovers—the ultimate in sex change therapy. These deependers look contemptuously down on the poor creatures who submit themselves to the National Health Scheme’s iniquitous “chop job”—free, but merely castrating. In their turn these castrati are condescending about transvestites—amateurs who lack the guts to face the knife. Then again, transvestites, a notoriously narrow lot, despise homosexuals for not facing up to their true nature and adopting drag. Lastly come the heterosexuals who are pitied by the homosexuals for not facing up to their true nature.

James was naturally determined to have a definitive operation—one that leaves the patient more or less in the condition of a woman who has had a total hysterectomy—but there was an unforeseen problem: English surgeons understandably refuse to change the sex of a married man. Fond as he was—and still is—of his wife, James saw the eventual necessity of divorce, but he wanted to do this in his own time and not at the behest of British justice. The only solution was to leave the country and put himself in the hands of Dr. B————in Morocco. And so after an idyllic family summer in his house at Llanystumdwy, James set off to see the Great Agrippa of Casablanca. No problems. He handed over a stack of traveler’s checks, worked on the Times crossword puzzle, shaved his crotch in cold water under the eyes of Fatima, “Mistress of the Knives,” and as the anesthetic started to work, said goodbye to himself in the mirror: “I wanted to give that other self a long last look in the eye, and a wink for luck.” (Sound effects: a street vendor playing a delicate arpeggio on his flute “over and over again in sweet diminuendo.”)

Jan awoke pinioned to the bed but astonishingly happy. As soon as her chafed wrists were released, she polished off the crossword puzzle—“well almost polished it off—in no time at all.” Jan was either lucky, or in starry-eyed gratitude she has glossed over the worst horrors of the Casablanca clinic—known to some alumnae as the “Villa Frankenstein.” (One case reported to me woke up with the desired aperture, but the Moroccan plumbers had made a fearful tangle of her tubes.) When the bandages were removed, Jan was conscious of being “deliciously clean” at last. The protuberances she had come to detest had been scoured from her. “I was made by my own lights normal.” Feeling a new girl, she sallied forth to meet other new girls. They were a weird lot:

…brunette, jet black, or violent blond…butch…beefy, and…provocatively svelte. We ranged from the apparently scholarly to the obviously animal. Whether we were all going from male to female, or whether some of us were traveling the other way, I do not know…. Some of us were clearly sane, others were evidently rather dotty…. Our faces might be tight with pain, or grotesque with splodged makeup, but they were shining too with hope…. All our conundrums seemed unraveled.

Elizabeth welcomed Jan back home as if nothing had happened. Welsh neighbors likewise put her at her ease by pretending not to notice anything amiss. But I suspect a more drastic change had taken place than anyone had envisaged. A skillful scalpel may be able to change a man into a woman, but it cannot change a man into a lady. Jan’s words to the Fijian cab driver were prophetic. What had James become but Mrs. Miniver, that quintessence of middle-aged, middle-brow, middle-class gentility? Jan was not just an anomaly, she was an anachronism.

The very beginning of Conundrum supplies a possible explanation for this Miniverish persona. James’s first intimations that he had been born into the wrong body came at the age of three or four, when he was crouched under his mother’s piano. All we learn about this crucial lady is that she was playing Sibelius at the time. The omission of all other information is surely significant. Can it be that a Miniverish Mummie was James’s exemplar? No, I am not thinking of whoever wrote Psycho, but of Balzac, who tells us somewhere that a parvenu will usually base his style on splendors associated with his earliest memories, hence the anachronism of so much nouveau riche display. Could a similar pattern explain Jan’s anachronistic femininity? Certainly the dates fit: Mrs. Miniver first came out in 1939 (the movie with Greer Garson followed in 1942) when James was about twelve years old, and where else but in the Times—James’s old newspaper—and over the pseudonymous signature of Jan (Struther), James’s new name.

Conundrum is thus a cautionary tale. Imagine taking all those thousands of milligrams of hormones; imagine the agony of all those operations; imagine being responsible for all that family pain, and then to end up a travesty of pre-1939 gentility! In her outmoded coquettishness—“my red and white bangles give me a racy feel”—the author is as much a caricature of certain feminine attitudes (in themselves caricatures) as those drag queens whom Jan dismisses with a shudder as “the poor castaways of sex.”

Jan admits that James’s much-vaunted travel books became increasingly overwritten; purple passages and flights of Celtic fancy proliferated as the author’s male hormones lost out to female ones. Since the sex change, however, Jan’s writing has taken on a women’s magazine chirpiness that was not there before. Now that she has become a woman, Jan apparently feels obliged to write for—and down to—other Mrs. Minivers, as witness the description of a typical day in her new life: Jan goes out shopping and stops for a gossip, but “not at all a feline” one. She is distressed when Mrs. Weatherby tells her that Amanda missed school, sympathetic when Jane complains about Archie’s latest excess. No longer interested in food—a depressing development—she briskly buys a bagful of shelled Brazils, where James would have lingered over langues de chat, and goes home to find workmen in her neat flat, and oh deary me!

One of them has knocked my little red horse off the mantelpiece, chipping its enameled rump. I restrain my annoyance, summon a fairly frosty smile, and make them all cups of tea, but I am thinking to myself, as they sheepishly help themselves to sugar, a harsh feminist thought. It would be a man, I think.

Well it would, wouldn’t it?

Jan defiantly concludes that there is nobody in the world she would rather be than Jan. Fine, but please lady, spare us those self-righteous sniffs. They are poor advertisements for your new self and a betrayal of your new sex.

This Issue

May 2, 1974

-

*

The New York Times Magazine, March 17, 1974.

↩