Here is a book on a subject of obvious importance; it is based on serious though unobtrusive research and meditation; and it is written in a lucid and unaffected style. Reading the early pages one has little doubt that one is in for a quite memorable course of instruction, and that one had better be thinking of the appropriate ways of celebrating an investigator of insight and originality. However, something goes wrong: the author’s hand, elegantly opened, stays open, the fist is never made, and the material dribbles away.

Mr. Clayre undertakes to examine the notion, which according to him is about two hundred years old, that work should be the central interest of every life. The antithetical faith, which he takes to, be of more recent origin, holds that the right course is to drop out of the cycle of production and consumption into freedom and nature. In between there is a third term, the “instrumentalist” belief that the object of working is to finance leisure and pleasure.

The first task of the book is to look at the tradition of the primacy of work. This tradition is middle-class-intellectual, to be sought among people who talk about physical labor rather than do it. Such people, says Clayre, are apt to dismiss any dissenting views held by the workers themselves, attributing them to alienation or self-estrangement or “false consciousness,” concepts which he thinks have not traveled well down the years that have gone by since the end of the sixteen-hour day. Believing that workers are entitled to their views, Clayre wants among other things to measure the gap that exists between those views and the doctrines of the intellectuals.

Many of the theories about work that are still current have eighteenth-century origins. Rousseau, who believed that membership of society entailed an obligation to work, wanted Emile to be a carpenter and avoid monotonous and repetitive labor, even though this was before the power-machines came in. Schiller argued that individual liberty would be possible only after a transformation of the state, and also introduced the notion of play—creative activity of a disinterested, Kantian kind—as the sole satisfaction of the legitimate demands of men living in society, and indeed an index of their humanity. Fourier thought work and play need not be divided and set great store by variety of tasks. The early Hegel saw machines as mechanizing workers, and sketched the concept of alienation.

Evidence of this kind suggests to Clayre that there may be “a tendency in critical concepts to outlive the cosmology and methods of argument which gave them their original force.” This is in fact a commonplace of the history of ideas; it might even be said to have outlived its own epoch. The classical instance is the survival for centuries of antithetical primitivisms, labeled “soft” and “hard,” and reflecting complementary attitudes to work. Both kinds are involved in the story of Adam, who lived in a paradise of pleasure but had to cultivate it: a situation Milton found a bit difficult, for having declared the work virtually unnecessary, a mere disinterested tidying up of superfluous growth with prelapsarian secateurs, he gave Eve victorious arguments for the division of labor. The interesting question about all such perennial survivors is not whether they are true today, but why thought and feeling tend, over extremely long stretches of time, to assume these forms of expression.

In fact it is not very surprising that, for example, the concept of alienation should be older than the machinery we now identify as its principal agent. There has always been repetitive labor and it has always been stupefying; this of course does not entail the view that powered machinery may not be more stupefying than nonpowered, or nonpowered machinery than repetitive manual labor. Mr. Clayre’s real point is that he is disinclined to believe that the stupefaction of workers is so great that they do not know what they are talking about, and this is why he is keen to prove that the intellectuals are too ready to apply to modern conditions “methods of argument” designed to deal with conditions as they were over a hundred years ago, closing their ears meanwhile to the views of the workers themselves. For this reason they perpetuate the error of William Morris, and are quite unable to understand that some people actually like machines and are fascinated by their precision, just as they cannot understand that workers rarely entertain lofty ideals of work in the manner of their betters.

Since loss of work entails the ruin of leisure—the two, by long habit, are thought of as complementary—people who work rarely waste their time in fantasies of total idleness. They do of course discriminate between different kinds of work; it needs no academic investigation to convince them that clockbound workers are worse off than men who regulate their own time, or that noisy work, or work carried out under strict surveillance, or work with a very short cycle, is more exhausting than work which, though physically tougher, is more varied or spontaneous. Most obviously, they are aware that hours spent at work are stolen from leisure, which is why the major effort of unions has hitherto been toward shorter hours and higher wages, rather than toward sophisticated improvements in working conditions. What they go for is more leisure and more money to pay for it.

Advertisement

It is when he turns to the question of what workers think about work that Mr. Clayre, it seems to me, begins to waver. He has little difficulty in demonstrating that nineteenth-century workers, unlike their bourgeois sympathizers, liked leisure and play more than work, and would not have understood Engels when he pitied them not because they had to work but because they had to work for money. This is strictly a gentleman’s worry. And even in Engels’s Manchester, work was inextricably involved with play—with the jokes, songs, and rituals of the workshop (in so far as masters permitted them) and the finery of the holiday processions, deplored by Marx for the waste of money involved. Then as now, says Clayre, workers set a higher value on play than writers do, which partly explains the gap between their views on work.

As my account no doubt suggests, Clayre is somewhat obsessed with this difference. And yet it cannot come as a surprise to anybody who is or has been a worker, or has known workers, to learn that they like playing better than working, and combine to improve the rewards of work rather than to make it more varied or productive or even safer. To develop an interest in Ruskin or Morris or Marx was a fairly sure sign of upward mobility and a changed style of life. The capacity of the working classes to spend all they earn, even in the best of times, though it invariably irritates the middle classes, arises naturally enough from their conviction that they spend the week doing what they do not freely choose to do in order to purchase the right to do as they please in their “own time.” There are plenty of reasons, no doubt, for thinking this an unfortunate or even a false attitude; perhaps, as Clayre suggests, there was a primitive state in which work and leisure were undissociated, where the satisfactions now associated with leisure were intrinsic to hunting or agriculture; but it seems clear that this is over.

At this point Clayre worries about the possibility that the lowering effect of repetitive work in modern factories may have a damaging effect on the worker’s leisure. The automobile worker often dislikes his job and does it only for the money; but it has tired him in a peculiarly destructive way and may have impaired his creativity in leisure tasks also. He cites some evidence that this is so, and it does not seem improbable. But on the whole his promised treatment of the workers’ view of the effect of their jobs on their lives is disappointing and sketchy.

There is a great deal of evidence he does not use, for example on the element of play in nineteenth-century work: the rough fun, the songs that not only lamented the passing of a traditional way of life but sometimes celebrated the virtues of the new order, the vitality of town life, the pretty clothes that the new money could buy, even the achievements of ur-Stakhanovite workmates, and the traditional craft obscenities. Clubs and unions fostered a class-ideology, and with it a new concept of the dignity of the working man. The music-hall songs of the later years of the century, a commercialized development of working-class play-songs, can be used to show how complex were the interactions of work, play, and status; such are the subjects of Martha Vicinus’s book The Industrial Muse, published last year. By comparison Mr. Clayre often sounds very abstract.

Moreover, like the predecessors he condemns, he concentrates on the theory of work, relying largely on Huizinga for what he says of play. It may be, as D.W. Winnicott remarks, that “the natural thing is playing,” but it does not follow that the concept needs less exploration than that of work, especially in a book like this. If work is the social reality, leisure is the space between it and the soul of the individual, the space in which he makes the rules, runs the clock, and is necessarily creative. It is the modern version of what Morris called creative activity and Marx free work. And it is, of course, precisely the space that advertising seeks to invade and corrupt. Of the forces which act upon playtime, and which, in their more complicated fashion, attempt to fulfill the failed prophecy of the nineteenth-century economists and keep labor at something like subsistence level by taking its money in exchange for trash, Mr. Clayre has nothing to say, though they must be at least as important as the carry-over of ill effects from tedious work into leisure; and they also have a bearing on the question of “false consciousness.”

Advertisement

We should need, in short, more generous and subtle notions of playcreativity and its enemies before we could add to Clayre’s book the final section it lacks. They would not be easy to develop, and we should have to be especially careful not to give play to our own false consciousness, for example by undervaluing leisure activities which are to us inexplicably tedious or insipid. On the other hand we should not simply ignore the intrusions of a stupefying propaganda into the space of play.

For want of such discriminations this elegant and in its way rather distinguished book seems in the end tentative and inconclusive. It is also, despite its initial claims, uninformative on the opinions of workers—further testimony, indeed, to that “gap in consciousness” between them and their intellectual sympathizers of which Clayre so often complains.

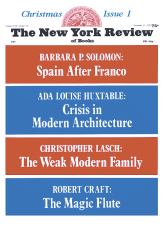

This Issue

November 27, 1975