Unity Mitford was the fourth of the six remarkable Mitford sisters. The eldest, Nancy, who immortalized her parents, Lord and Lady Redesdale, in The Pursuit of Love, married the original of Evelyn Waugh’s character Basil Seal. The youngest married the present Duke of Devonshire. The third, Diana, married the leader of the British Fascist movement, Sir Oswald Mosley, was imprisoned with him during the war for three years as a security risk, released by Churchill when the threat of the invasion of Britain had clearly passed, and has just written a vivacious memoir entirely unrepentant and complaining of being uncomfortable in prison. Jessica (“Decca”) is the best known in America for her books on morticians and prisons: now married to the labor lawyer Bob Treuhaft, she first ran off with Churchill’s nephew, Esmond Romilly, to fight on the Spanish Republican side in the civil war.

It was Unity’s distinction to win notoriety on the other side as the unbridled supporter of the Nazis and the personal friend of Hitler, whom she often saw when she lived in Munich during the 1930s. On the outbreak of war in 1939 she shot herself through the head in a Munich park, was invalided back to England, and died nine years later a wreck. She was a big, beautiful blonde, but far from dumb. As with those other sisters, the Brontës, the intensity of their family life made the Mitfords create a world of their own. For them the family resembled a fortress from which they made assaults on the society of their youth; and they were greatly set up when they managed, each in her own way, to shock it.

Last fall a storm broke in the teacup of London literary society. The rest of the nation can hardly be said to have noticed it, the fall of the pound was not noticeably accelerated, and the fabric of English life, somewhat threadbare these days, withstood the strain. But if one listened to the pungent rumors and delectable gossip which flew around as the storm raged, the shores should have been strewed with the wreckage of reputations and friendships. The typhoon struck Mr. David Pryce-Jones’s biography of Unity Mitford, and the Horsemen of the Apocalypse riding the whirlwind were the three surviving Mitford sisters living in England.

They declared that the biography was unauthorized, inaccurate, and unfair. They denounced Mr. Pryce-Jones for going around and passing himself off as persona grata with the family, when in fact he was not, and on those grounds inveigling many of Unity’s acquaintances to give him information which he then twisted to suit his thesis. When his informants complained and asked to be shown the proofs of what they were alleged to have said, Mr. Pryce-Jones then—so the indictment read—either forgot to send proofs or left in offending passages which he had agreed to delete. His book was tendentious, unimaginative, and insensitive to the tragedy which befell Unity Mitford’s parents, and toward the delusion which afflicted and finally destroyed the girl herself. After all, was she not at an age when people exaggerate, posture, do foolish and say unforgivable things?

By now, with the wind howling, some who had been interviewed by Mr. Pryce-Jones, like those in the parable who were bidden to the great supper, all with one consent began to make excuse. They wailed that they had been misrepresented, they had never said Unity was halfmad, they were misquoted, the errors in the book were so gross that it was impossible to correct them. Their letters of exculpation were then circulated to various potential reviewers. And now the publisher of the book, George Weidenfeld, found himself caught in the gale, facing imperious demands that he should withdraw it from publication. He replied that he had faith in David Pryce-Jones’s integrity and declined to interfere.

The author showed to the London Sunday Times the correspondence he had had with the very people who now were declaring that he had tricked them, producing their corrected proofs and the deletions he had made in deference to their wishes, and expressed his astonishment that people with whom he had had, until then, friendly relations and who had overtly helped him, should now repudiate what they had done. He began to receive letters familiar to those who were hostile to Munich or Suez, accusing him of being a traitor to his class. It is even alleged that an attempt was made to drum up the support of his father, Mr. Alan Pryce-Jones, who received a card saying “Can’t you call your boy off?” The former editor of the Times Literary Supplement, however, lying like Drake in his hammock a thousand miles away in Newport, Rhode Island, declined the summons.

At any rate, the affair added some new names to the usual list of reviewers, the most dazzling piece of invective being written by Lord Lambton, the Tory junior defense minister under Edward Heath, a Valmont of our times whose liaisons became ultimately too dangerous, so much so that he had to resign his post after an infamous paperrazzo photographed him by trickery in bed with two call girls—a thing that might happen to fair number of people these days. Lambton not only savaged the book but wrote the most disagreeable things about its publisher, who in his view had insolently accepted a peerage, and occupied himself more with Beautiful People than with books. Finally, in the classic gesture of the upper classes, the three sisters sent a grave letter of protest to the Times.

Advertisement

Since the Conservative government of 1964 fell and the days of Macmillan were over, the British aristocracy has kept a low profile. Sometimes a young scion hits the headlines when arrested for possessing pot, but most members of the aristocracy have retired from the political scene and are beginning like their Continental counterparts to live in a world of their own, far more harassed than the Continentals by taxes, but unlikely to exert much influence in a Conservative party ruled by Margaret Thatcher. Nor are they attracted by the squalor of life as an MP in the House of Commons, which no longer brings social rewards, and leaves a man less time for leisure than even a hardworking businessman can except. What was it that sparked off this sudden eruption?

All sorts of theories have been canvassed. Was it an old dispossessed Establishment snarling at the heels of the new Establishment which Harold Wilson’s patronage had created? Or was it the guilty memory of the pre-1939 days when two or three dukes, a covey of lesser peers, such as Unity Mitford’s father, a few generals and admirals, and substantial numbers in the City, including one Jewish merchant bank which bought German bonds, backed Hitler as the bulwark against Communism and contrasted his achievements with those of their own ineffective parliamentary democracy?

Or was it caused by a Jewish conspiracy? Conspiracy theorists noted that David Pryce-Jones’s mother was a Fuld and sister to Baroness Elie de Rothschild, that George Weidenfeld is a Zionist, and that the editor of the TLS, Mr. John Gross, insisted that a hostile review should be cut. Mr. Pryce-Jones prefers the theory that, so far from being Jewish, it is a Whig conspiracy at work. He is quoted as saying that the “desperate lengths people will go to defend their social position” shows how the aristocracy resists egalitarianism. The rumpus reopens the question of how many Englishmen “were prepared to compromise with Nazism to save their own positions.”

None of these theories is tenable. The truth seems to me to be simpler. Although this seems unknown to the author, his book is an indictment of the aristocratic notion of politics. According to this notion, it is a delusion to imagine that politics are about ideas. They are about people. Inevitably, you have to take sides, and in order to explain why you trot out reasons, and sometimes even invoke principles. But these are of no importance whatsoever. Moreover, politics are a matter of luck: you can easily be caught on the wrong side. If several of your ancestors lost their heads on the scaffold, or their lands, or were disgraced, or quarreled violently with the leaders of their party or faction, you are not much disposed to see the political world in black and white. No one in politics can be consistent, each has to compromise, do U-turns, lie brazenly when things go wrong, admit bounders and blackguards to his circle and—worse—dim, dull dogs who are useful at certain technical tasks but intolerable bores who don’t understand one’s jokes. Courage and flair are the chief political virtues, fidelity to principles or manifestoes a chimera.

In the practice of aristocratic politics, the suit of tu quoque is always trumps. Who invented concentration camps but the British in the Boer War, and who dares still to pass them off as “corrective labor camps” in the Soviet Union? For every My Lai there is a Têt massacre. If the South African police shoot a hundred brace of Africans, elsewhere in Africa whole tribes are being exterminated by the rulers of states celebrating in a blood bath their liberation from imperialist order. If the argument gets rough, the aristocrat is quite likely to end up calling his opponents names as he learned to do in the nursery: Suez-Cuba, Dachau-Gulag Archipelago, Lidice-Katyn, Coventry-Dresden.

Foreigners are never to be trusted. They always put their own interests first as France did in 1940; and a de Gaulle is to be treated as a pawn, pushed about the board to suit the British convenience. When the pawn, in the course of time, becomes a queen and checkmates the British entry to Europe, this is proof that gratitude, ententes cordiales, or ideological alliances are impostures. It is vain to hope that one is always going to be on the “right” side, because all politicians, whatever their side, have feet of clay. You convict yourself of being historically illiterate if you say that Gladstone was “right” over Home Rule for Ireland. When except possibly between 1937 and 1940 was Winston Churchill “right”? As late as 1937 he allowed his expression of hope to appear in print that Hitler despite his methods might turn out to be a great figure whose life might enrich mankind. If you identify yourself with a discernible historical movement, or embrace a political ideology, you will end by double-dealing and using double-talk to explain away your connivance at conduct just as odious as that which you condemn in your enemies. Never blame people for the consequences in politics. Reformers discover that the consequences of their reforms are always remote from what they intended.

Advertisement

The antithesis to this notion of politics is held by part at least—and perhaps the most serious and high-minded part—of the intelligentsia. As a theory it owes a good deal to Calvinism, in which for every deed and every utterance one is accountable to God. Utter a careless word and, as a consequence, some weaker brother or sister enters into a life of sin. There is a direct causal chain which links evil to evil. That is why discrimination is a peremptory duty, and the identification of error in others a positive injunction.

It has been observed that the London intellectual establishment living in the political center of their country and mixing in the political and mass media circles are notably more indulgent and less rigorous than their counterparts in New York. There, so it seems to the English, the stand which one took on Vietnam, civil rights, Kennedy, McCarthy, Oppenheimer, Hiss, Stalin’s purges, or the assassination of Trotsky is regarded as evidence either that one is—well, if not in Calvinist terminology sanctified, at least not of the devil’s party, or culpable of error so grave that public apology is only the first of a number of humiliations before rejoining the elect. The precise date at which one ceased to be a supporter of communism, or opposed the loyalty oath, or deserted the Kennedy camp, or opposed the war in Vietnam is a matter which can divide friends and dissolve alliances. Politics is indeed seen as a battlefield between good and evil; and if George Kennan, in theory, or Kissinger, in practice, attempts to throw doubt and sow confusion on this contention, he is likely to be regarded with odium and lucky if he escapes with dismissive comment.

Such a view of politics dismisses the aristocratic notion which puts first loyalty to family, class, and country as little better than the politics of the Mafia. To the intelligentsia it is entirely just that the admirers and, in the case of Unity Mitford, frenzied supporters of Hitler should be disinterred and their corpses gibbeted. It must be admitted that in the Thirties the British right up to the rape of Czechoslovakia were not so much divided as in a fine muddle where Germany was concerned. The mass of the people may have despised Hitler, but the slaughter of the First World War made them in varying degrees pacifist. That was why it was easy for Chamberlain’s supporters to denounce the critics of appeasement as warmongers. It was this which led the Labour Party to put itself in the absurd position of calling simultaneously for a stand to be taken against fascism while voting against rearmament. Veterans of the First World War in both countries had formed “Never Again” associations, and among Conservatives there was the hope that somehow Hitler could be persuaded to turn against communist Russia rather than break up the Europe of Versailles.

Nevertheless, so the argument runs, this confusion of purpose does not alter the fact that virtually the whole country despised the Nazi movement and its methods. Even Unity’s father, who in his anticommunism supported Nazi Germany, shook his head over her flamboyant advocacy of the Nazi cause, her hobnobbing with Hitler and her association with Goebbels, Streicher, and the SS. For it is also true and highly significant that in England Mosley’s fascist party never at any time looked like a mass movement. In fact the number of active supporters of Hitler and Nazism was miniscule. No matter what excess or bestiality the Nazis committed, Unity Mitford would glory in it. According to this view of politics she was a disgraceful ally of an evil regime.

To the adherents of the aristocratic notion of politics this is almost irrelevant. To them, Unity Mitford merely backed the wrong horse. They declare that it is scarcely credible that any of the convulsions and calamities of Europe in the war years can be attributed to the antics of a girl who enjoyed, like her younger sister on the antifascist side, the delight of shocking her own class by her support of an unpopular cause. At any rate, when she shot herself, leaving a note to Hitler imploring him to spare her people, she showed she was no traitor to her country like the communist renegades Burgess, MacLean, and Philby. After all, who cares about dotty opinions? What mattered was her high spirits, the fact that she was the favorite sister in the family, that she was amusing and lovable. Why then write a book about someone of conspicuous unimportance which will give pain to her family who cherish her memory as a person?

In the hands of Michael Oakeshott, and with considerable modification, the aristocratic notion of politics can be erected into a formidable political theory. But there is one inconvenient fact about Unity Mitford which this theory is incapable of assimilating. She was a virulent anti-Semite. “I want everybody to know I am a Jew-hater,” was her charming contribution to Der Stürmer. Mr. David Pryce-Jones quotes two examples of her sensibility. When, after the occupation of Austria, 5,000 Jews were left on a breakwater or to float downstream on the Danube with no hope of refuge, she rejoiced: “That is the way to treat them, I wish we could do that in England to our Jews.” When she needed an apartment in Munich she was offered by Hitler a choice from those requisitioned from Jews after the Kristallnacht and inspected them while the Jewish families watched her.

It is interesting to observe how her apologists meet this challenge. Lord Lambton’s audacity is breath-taking. He begins by praising the Jews in England for their silence. Not once have they raked over the embers of the past. But Pryce-Jones and Weidenfeld betrayed “the dignity and moderation with which the Jewish race reacted to their terrible sufferings in the last war…. These two have sacrificed the accuracy and truthfulness which have been the proud hallmark of the Jewish establishment since the War.”

What do these last three words mean? Does Lord Lambton follow Sir Oswald Mosley in believing that the Jews were not accurate or truthful or dignified or moderate before the war? For that is the essence of Mosley’s apologia for his anti-Semitism—he was merely trying to prevent a Jewish clique from involving Britain in a war with Germany; and to his misfortune, he failed. Apart from that he really had nothing against them. But as Mr. David Pryce-Jones pointed out in his review in these pages,* Robert Skidelsky’s biography of Mosley suppressed the fact that Mosley openly congratulated Streicher and that his fascists went in for Jew-baiting in London—not in the City where allegedly these dastardly conspirators lurked organizing an international financial plot to plunge Europe into war, but in the East End where the poor Jews lived, refugees from the Russian pogroms at the turn of the century.

The excuse most frequently proffered in Unity Mitford’s defense is that the six million dead in the gas ovens lay in the future and no one before the war could have envisaged the Final Solution. The truth is that the concentration camps were set up long before the war and if their first inmates were mostly the Nazis’ political opponents, individual Jews also were imprisoned and collectively Jews were persecuted. Why did the fortunate emigrate if it were not so?

Moreover, as Professor Trevor-Roper and other historians have demonstrated, to the discomfiture of those who enjoy trying to palm off Hitler’s wickedness onto Chamberlain, Daladier, or the impersonal forces of history, Hitler’s own published writings before the war declared exactly what he stood for and what he set out to achieve. Here was a regime that was openly willing to plunge Europe into a major war in order to attain its ends and that determined to eliminate not merely its political opponents but citizens who happened to be Jews and were law-abiding and patriotic members of their country. The young are often cruel and spiteful and acquire in their own eyes an identity only if they spit upon what is accepted and deliberately give pain in so doing. But to embrace such a cause was evil.

Indeed, to do so broke with the aristocratic notion of politics. For what distinguishes this code from that of the Mafia is that honor is not interpreted as omertá. Why in England was Jewbaiting rejected as disgusting by the right—why, long before Hitler, were those, such as Hilaire Belloc or Cecil Chesterton, who tried it driven out of national politics? Why was the slander by some despicable German playwright that Churchill ordered Sikorsky’s aircraft to be sabotaged seen as ludicrous? The reason is that such behavior breaks the code of conduct governing English aristocratic politics. For Unity Mitford to fawn on Hitler and Streicher and embrace their principles was to break with the political tradition to which she belonged.

Should Mr. Pryce-Jones have given pain by writing this book?—for, of course, the silly attempts to hamper its publication sprang from pain. Intellectuals are often puzzled that people mind seeing family skeletons revealed. For them the family is an institution of repression and restriction; and it must be said that noble families usually rise resilient when skeletons fall out of the cupboard. The trouble is that Mr. Pryce-Jones can hardly be said to have written the book which the subject deserved. Fearing perhaps that his judgments would be challenged unless he produced his evidence, he has emptied his notebooks into his biography and much of the material is deadly, trivial bric-a-brac. The sound which emerges from the pages is that of the yakking of debutantes; and the German names and phrases quoted, though free of the grosser mistakes in the English edition, still contain some slips.

Even if he was unwilling to analyze, fortunately for them, the class into which she was born and its manners, or even the society of her young contemporaries in which the future President Kennedy learned to play as a boy, some comparison might have been made with others of her age who shot off to the extreme right or the extreme left. In such a light there is a complexity; but it is not a complexity of Unity Mitford’s psychology so much as the complexity of the moral issues which he raises that are worth exploring. As it is, the main merit of the book is its success in conveying for those who were then young and belonged to the upper classes a whiff of those sad years, unforgettable yet best forgotten.

Since the days when they were young, the Mitford sisters have been news; and those who live by the sword of publicity have to accept that if they fall from grace, whether or not deservedly, they will perish by the sword. Unity Mitford was an insignificant bit part player in that particular act of history; but if you go on the stage, your family cannot object if the critics judge you to have put on a bad act. The only response, combining dignity and compassion, is that which the one Mitford sister, Decca, who did not join in the chorus of protest, made when called to comment by the press. “I am mourning my sister.”

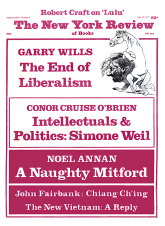

This Issue

May 12, 1977

-

*

NYR, September 16, 1976.

↩