One flaw in a human rights foreign policy is that human rights are not as pervasive as human righteousness, and the self-esteemed revolutionaries who monopolize righteousness in Russia and China will reject American tutelage. But if the Kremlin leaders do it a bit defensively as Europeans once removed, the same cannot be expected of Peking. To rule by virtue of virtuous conduct was a Chinese specialty long before Christianity and Roman law taught us that individuals have immortal souls and civil liberties. Confucian morality stressed duties, not rights, as the glue of social harmony, and individualism is still a dirty word in the People’s Republic. The fact is that the human rights concept, though enshrined in a self-styled universal declaration, is culture-bound. Thus it assumes the rightful supremacy of law and due process over moral teachings, but right-thinking Maoists, who don’t tolerate a legal profession, scorn the letter of the law and exalt Mao’s principles of moral conduct. They view our civil rights as a form of political affluence associated with the property rights of our economic affluence, not something China can use. Chinese individuals relate to state and society in a different way.

The difference between Chinese and Americans is perennially fascinating, almost as fascinating as the difference between men and women, though less tangible and not as easy to investigate. Whether the Chinese can learn anything moral from us, beyond the negative examples they now see in our streets and media, is quite uncertain. Since they have lived crowded longer than we, perhaps we have more to learn from them in both material ecology and personal self-discipline. Buddhism as well as Confucianism taught them that unease and disorder are rooted in human desires, the very things our consumerist advertising and our travel, health, and sex industries try to cultivate. Exciting ourselves as we do in the name of individualism, we have problems that collectivist China hopes to avoid. Yet our individualist faith is central to our culture, and Americans in China who are not mesmerized by culture-shock invariably seek personal intimacies there, hoping to exchange private thoughts, share perspectives, and enjoy a unique experience. To the organizers of China’s new order, such conduct is bourgeois, subversive, and dangerously infectious. But just as the Western competition in the 1890s was to see which explorer could get closest to Lhasa before being thrown out of Tibet, so our present-day visitors to the People’s Republic compete to see who can have the most heart-to-heart exchange with a Chinese person.

Orville Schell visited China in 1975 in a party of twenty Americans aged eighteen to sixty who not only had a two-week tour of Peking, Yenan, Sian, Mao’s birthplace, and Shanghai but also spent a fortnight or so working part time in a Shanghai factory and another period in the fields of the model Tachai Brigade in Shansi. This special opportunity to be with ordinary Chinese, “the masses,” was arranged by the trusted Hinton family (of Putney School in Vermont) who have long been a PRC beachhead in the US. (Bill Hinton’s Fanshen is the classic account of land reform in the late 1940s.) At age thirty-five Schell was well prepared with Chinese language, historical studies, and two years reporting from Vietnam and elsewhere.

In the People’s Republic is one of the best of the I-saw-China books that have mushroomed since 1972 because Schell mercifully screens out his American colleagues. Instead of recording the considerable happening that this junket must have been, he concentrates on his personal contacts with Chinese and his own ensuing reflections. His search for intimate friendship and mutual exchange is frustrating. First, his Chinese acquaintances are uniformly not interested in the US, which is beyond their ken and certainly beyond their concern. Even worse, they seem genuinely uninterested in the unique assemblage of preferences, self-images, and personal experiences that adorn and identify an American individual. On the contrary, the Chinese are collectivists seemingly eager to be just like one another, to work together and not separately, to conform and not deviate, and to get their satisfactions from the approval of the group and constituted authority rather than from realizing private ambitions or any form of self-indulgence. This unconcern for self, this self-realization within the group, not apart from it, is of course not a transient vogue but the product of many centuries of Confucian family collectivism, now redirected to “serve the people.”

For Western journalists, those world-weary scions of individual enterprise, this lack of selfishness is hard to take. Schell faults his Hong Kong confreres for defending their impure outside world by magnifying impurities within China—for example, they persist in reporting amateur prostitution in Peking and Shanghai, mainly for foreigners, whereas the really significant thing is the lack of prostitution in China generally. “China’s purity seems intolerable to those of us on the outside who live in a state of such permanent compromise and ambiguity…we cannot allow the Chinese to become intelligible unless we see them as flawed…by greed, lust, selfishness, and self-gratification.”

Advertisement

Walking to work from dormitory to factory, Schell falls in with a clear-eyed, handsome girl named Shao-feng. But a man and woman seen alone together in public are usually considered engaged. Finding herself in this one-on-one boy-meets-girl situation, Shao-feng calls to a girl friend to join them and then is more at ease. Later in the theater she inadvertently sits down next to Schell, who hopes to get further acquainted. But his male Chinese companion at once sees the problem and simply changes seats with him. Schell wonders if the Chinese “have learned to defy the sexual gravity which keeps the bourgeois world so preoccupied and earthbound.”

“Americans are forever trying to get the Chinese to say something illuminating on the subject of their personal relations. They will sit at a table full of commune cadres and officials and ask and expect an answer about premarital sex.” Schell concludes that Chinese downplaying of sexuality is a “question of values and not repression.” He finds “a directness and a matter-of-factness evident in relations between the sexes.” But “there is little time and no encouragement for hedonistic activities.”

The same abstention applies to national political issues and decisions, which are discussed extensively but always in the past tense, after the issues have been decided. (In the old days the masses took no part in politics; today they are still wary.) Schell remarks that Chinese would rather talk on “past issues that have been resolved than on present issues that are still being struggled over.” Live issues still undecided are no-news, non-topics. Only dead issues specifically embalmed in the party line can safely be discussed. It is like knowing all the plots of old movies but never seeing a new one unfolding in motion. One senses that the inventors of paper, printing, books, and civil service exams learned long ago to wait for the established texts and not pop off orally and prematurely on current events. Schell concludes that “whatever the Chinese talk about most is precisely what they have the greatest trouble doing. The Chinese talk about criticizing authority a great deal…. They strike me as extremely obedient, almost paralyzed, in the face of authority.”

At the Tachai Brigade store Schell meets a fruit tree specialist, Mr. Huang, who has been “sent down” to work at Tachai—an intelligent and interesting man with whom he enjoys conversing. Schell asks permission and arranges to see Mr. Huang again. That evening he stays home from the movie to write and sleep. Suddenly the overhead light is on and the cadre in charge tells him that the date with Mr. Huang has been cancelled and since Schell is sick he will stay in next day and not go outdoors. Schell realizes that he has been too inquisitive, “seeking individual experiences, not bending totally to the schedule arranged for us.”

While Orville Schell finds little individualism, though plenty of personality, among the masses, Roxane Witke finds both to be flourishing in the woman leader, Chiang Ch’ing. Roxane Witke got to Peking in July 1972 as a recognized China specialist (out of Stanford, Chicago, and Berkeley by way of Binghamton) in order to study Chinese feminism. After Chiang Ch’ing suddenly enlisted her services as a female Edgar Snow and gave her sixty hours of self-revealing discourse, Witke faced a problem: translated transcripts, after the first one, were in the end not forth-coming but she had her own copious notes of a week of marathon sessions with Chiang Ch’ing at Canton plus many photographs, and other exchanges in the year after. Chinese officialdom urged her to forget it but she persisted, trying to fashion an intelligible biography and set it in the historical context of the Shanghai stage and film world of the 1930s, of Yenan in the 1940s, and especially of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Edgar Snow’s task in taking down Mao’s youthful saga in 1936 was much easier. Witke’s account is more diffuse and less definitive. It is a big book, handsomely produced with unique photographs, a useful chronology, lists of terms and persons, and research notes. Comrade Chiang Ch’ing, published six months after its subject’s fall from a decade of power, has been given a Time cover story. Critics, whether disappointed or enthusiastic, cannot deny its uniqueness, but it will take some time to judge its historical value.

First of all, Chiang Ch’ing’s story of her career is a political document, self-serving, incomplete, an island of evidence in a broad ocean of secrecy. Imagine a history of the New Deal based on only the Congressional Record and the ex parte memoirs of Harold Ickes! Chiang Ch’ing’s testimony, though partially vetted by Chou En-lai and others, seems strictly personal, not a product of collective judgment on how to characterize the past. The counter testimony of her predecessors as cultural arbiters, the “Four Villains” she purged (Chou Yang, T’ien Han, Hsia Yen, and Yang Han-sheng), of course is not equally available, nor are her statements, direct or indirect, on power relations and leadership decisions either formally authorized by her or fully documented, if at all. The book is not based on tapes like Khrushchev Remembers but presents Chiang Ch’ing’s oral views and recollections as translated by her interpreter and recorded by Roxane Witke in 1972 and subsequently combined with Witke’s own research and interpretation. Two voices speak but it would not be correct to put Chiang Ch’ing’s in quotation marks. The author presents her own record of what Chiang Ch’ing said and then her own comment on it. The reader has to shift gears accordingly.

Advertisement

The publishers play up their author’s metamorphosis from honored guest to official enemy of the People’s Republic, denounced for receiving state secrets from the anti-party traitor that Chiang Ch’ing has now become. Given the secret style of government and the moral obloquy heaped upon ex-power holders in Peking, this can be expected. But Americans trying in their more open, pluralistic world to penetrate the mystery of Chinese politics can feel indebted to Roxane Witke for her painstaking effort to put Chiang Ch’ing’s story together, even though the result is only as reliable as the star witness.

In brief, her early life is presented as one of dire poverty and harship but determination to rise as an actress and join the revolution. She was accepted by the Party in 1933 at age nineteen and, although never an insider in the organization, she worked in the precarious communist underground in Shanghai while becoming known as the actress Li Yun-ho and later as the film star Lan P’ing. She reveals that in 1934 she was jailed for eight months by the Kuomintang (this is now used against her) and released only through the intervention of a foreigner from the YMCA.

When she reached Yenan with this revolutionary record in August 1937 and took the name Chiang Ch’ing (Azure River), Mao Tse-tung was forty-four. He took an immediate interest in Chiang Ch’ing. Her big city sophistication complemented his country background. At twenty-three she had enough feminist ego to stand up to him and enough resilience to learn his rustic way of life. During the North Shensi campaign of the civil war in 1947-1948 she stayed with Mao and Chou En-lai in villagers’ hovels, often marching by night, eluding the Nationalist forces. From this harsh experience her health suffered (tuberculosis, cancer, enlarged liver, etc.). She was ill during most of the 1950s and made four trips to the USSR to recuperate. Only in the late 1950s did she begin to emerge in party councils and campaigns as a leader in her own right.

Chiang Ch’ing finally entered history as an apostle of the Cultural Revolution. After some experience in land reform, she went back to Shanghai in 1959 and began her attack on feudal and bourgeois holdovers in the performing arts there in 1962. “She had convinced the Chairman (as she had argued for years) of the compelling need to gain the upper hand ideologically by vigorously promoting proletarian supremacy in the arts.” She felt that China’s cultural life, unlike the economy and polity, had not yet been cleansed of the pre-liberation evils.

Chiang Ch’ing’s approach to the cultural superstructure of revolutionary education, art, and literature took off from Mao’s formulations and methods for thought reform devised at Yenan in the 1940s. Yet as Witke remarks, “The conflict between totalitarian political authority and creative independence is unreconcilable—universally. But in the rhetoric of Mao Tse-tung’s regime that insoluble contradiction was grossly over-simplified to supply evidence of the ‘struggle between the two lines’: the correct line of Mao…and the incorrect line of his opponent of the hour.” In short, Mao used thought reform politically to show that “people who disagreed with him intellectually were by the same act disloyal to him personally.” This approach suited Chiang Ch’ing, who bitterly resented her nonacceptance by the Party’s cultural commissars of the 1930s. In the 1960s she cashiered them as reactionaries (they had dominated the scene for thirty years) and took their place.

As Mao’s greatest campaign unfolded, Chiang Ch’ing drafted key documents, began to reform the Peking opera, soon made public appearances and even speeches. She became a member of the People’s Congress, then cultural adviser to the army, and finally in 1966 one of the Cultural Revolution group appointed to direct the whole campaign. By its end in 1969 she was at the top—a member of the Politburo and in charge of all cultural activities. Including five years of primary school, she had had only eight years of education herself. She let the universities remain closed for five years, stopped all unauthorized book and film production, and sponsored the creation of eight revolutionary operas that blanketed the country with black and white stereotypes of villains thwarted by model heroes and heroines, fists clenched in determination, eyes glaring in righteous defiance. This proletarian morality held sway until Mao died in September 1976 and his widow was arrested in October.

Evaluation of Chiang Ch’ing’s role in history will depend on one’s view of the Cultural Revolution, which had a bad press outside China. Photos showed rampaging teenagers waving their little red books of Mao quotations. To purge the Party bureaucrats Mao mobilized these adolescents as Red Guards, but millions of them later had to be dispersed to the countryside. What did all the chaos accomplish?

Our American incomprehension of Mao’s second revolution stems, I think, from our ignorance of China’s ancient ruling class tradition which was its institutional target. Unfortunately Mao’s quest for an egalitarianism that would bring the masses of China into modern life coincided with the technology of mass communications that foster central control. The revolution’s push for equality in social relations and living conditions has not dimmed its need for top authority. The Party dictatorship has therefore manipulated the masses even more actively than the old scholar-official elite used to manipulate the lao-pai-hsing or common people with the skills of Confucian-Legalist statecraft.

Communist elitism is implicit in the whole mystique of the masses to which Chiang Ch’ing subscribed. She felt that to go among the masses, be accepted, win their confidence, and lead them was the revolutionary’s highest function. As Mao put it, “only by being their pupil can he be their teacher. If he regards himself as their master…he will not be needed by the masses.” But despite this rhetoric China’s politics remain authoritarian. Elitist government of the sophisticated type that has held 800 million Chinese together cannot be soon foregone. From this perspective what outsider can say that Chiang Ch’ing’s simplistic operas were not efficacious among China’s masses? Her decade of power can be fully judged only in the light of facts we still lack.

For our present purposes one conclusion seems evident—a selected elite committed to governing by egalitarian models and maintaining its established authority over the mass of the populace cannot be expected to embrace a foreign and essentially bourgeois creed of civil liberties. Before we beat the drum of human rights in our China policy, we need to sort out global universals from culture-bound particulars and find common ground. To many Chinese much of our liberty seems closer to license. Let us grant that neither of us can be a model for the other and get down to the business of human survival together.

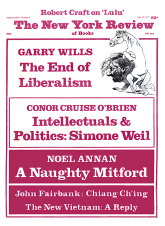

This Issue

May 12, 1977