These two novels are by American writers in the prime of their reputations who now live in England. Each novel is set in New England, and each is about a family, and about a family romance. Neither is proof of what has recently been asserted—that the English and American languages are diverging. In spite of the American vernacular they need to use, and in spite of the ethnic readings which each of them invites, neither is unmistakably the work of an American, rather than an Englishman: indeed, the ethos, or ethnos, of Theroux’s novel could, in part, be called Anglo-American. David Plante’s book is grave, tight, and deliberate. Paul Theroux’s is loose and approximate, fast-moving, given over to impact and commotion and emotion. Never a dull moment.

Mr. Theroux’s Picture Palace examines the relationship between the personal life of an artist and the art it produces (or, as we shall see, doesn’t produce). The story is told by a celebrated photographer, Maude Coffin Pratt, born in 1906 and now in her seventies, who is engaged, as the sole surviving tenant of the family house on Cape Cod, in looking through her old pictures, piled in the adjacent windmill. With her is trendy Frank Fusco, who is mounting a Maude Pratt retrospective, bedizened with stereophonic sound effects. This work causes charming, ill-natured Maude to resuffer her past life.

At one point she had come to realize that she was

a photographer for love. Orlando was the reason for my camera, and he would make it superfluous. I had no ambition beyond tempting him to its darkened side, and while my fame was crucial to this it struck me as foolish to pursue the lonely distraction of art beyond the room where we made a sandwich of our passion.

Orlando is her brother, and her designs on him are thwarted when she finds that, having been prepared by her for incest, he chooses to commit it with her sister Phoebe instead, in the windmill. Maude witnesses and records their embrace, and then, for a term, goes blind, staying on, Agonistes, at or around the mill with these slaves of passion, her screwing siblings. For all its fast moving, this is a densely literary book.

It is also a romantic book, evoking as it does a commitment which takes two people out of the world, a commitment which Maude aims at and misses. She dreams of Orlando and herself as “two images stealing together, as if we existed as fixed lovers in a field beyond the moon. Our ecstatic light-beams twisted toward earth, brother and sister, to be joined.” She is “fascinated by double images,” and imagines the witnessed incestuous embrace as a meeting of doubles. But, in modern times, duality is a matter of more selves than just two. She learns that “schizophrenia is merely a mistake in arithmetic. When I heard someone described as a split personality I thought, Only a schizo? Why choose two lives when so many are available in us?” She eventually imagines that her brother and sister had lit on her photograph of their embrace, and that the discovery had persuaded them to drown themselves. They had, in fact, drowned themselves. “They went out too far,” explains the father of the brood, and Maude makes romantic sense of his un-comprehending words. In all this we can recognize a traditional language, which knows no difference between England and America.

Orlando to the windmill—the book may be alluding to Virginia Woolf, and to the well-known seaside house and lighthouse in her fiction, so that it is surprising that she should be among the few celebrities of the period who do not put in an appearance in the book as Maude’s subjects. Those who do appear include Waugh, an even crosser patch than his portrayer, and stony Stieglitz, the photographer, with his mustached sneer, and they include the living. Graham Greene is revealed as wise and raffishly urbane: “I haven’t seen any pornography since they legalized it.” Maude laughs at this: “it was so like him.” D.H. Lawrence appears, and is treated with loathing. His beard doesn’t grow right, and he has the bad breath of a man whose lungs are not right either. He intones about darkness to the adolescent Maude, who is later to have thoughts of her own on the subject. Worse is to follow. “He said, ‘Those are my loins,’ and bumped me, ‘and that’s my willy,’ and bumped me again.”

Early in the book discomfort ensues with the feeling (mine anyway) that Maude is a man. She is aggressive, assassin-like, is rarely civil, wants to punch Frank in the mouth, and belches her disapproval of his retrospective in his face. She is meant to be hermaphroditic, longing to turn male and mustached with age. But it occurred to me that some of her pugnacities were less like those of any conceivable Yankee virago than like those of her compatriot Robert Frost, as they have been recalled by the disenchanted. Then Frost himself turned up in person on the page: an “utter egomaniac,” the biggest son-of-a-bitch I was ever to photograph,” “monologuing to a group of admirers, a whopping earache of complaints against his family.” But Maude is not very different, more son-of-a-bitch than bitch. Picture Palace explores the wilder shores of American androgyny, and a conception which transcends both sex and shore—that of the famous and cantankerous old artist who gets to punch the world in the mouth.

Advertisement

The writer’s habit of allusion and his recruitment of real people demonstrate that Maude inhabits an Anglo-American literary culture. When she writes that “home is such a tragic consolation of familiar dullness—that tree, this fence, that shrinking road,” we reflect that Philip Larkin has a poem called “Home is so sad,” whose last line is: “The music in the piano stool. That vase.” Such echoes add complication to a prose which is vivid and deft, but which is sometimes strained and uncertain. Maude is a purple crosspatch, and once you’re aware that the typesetter is making mistakes you start to worry over her eloquence. “The city was a steepness of remarkable air masses shaped by the specific columns of granite and fitted like a Jungle gym in impressive bars of voiceless smoke that had displaced the city.” I am lost in that gym. “Luxuriating in slyness, enjoying a kind of lover’s heartburn”: what kind of heart-burn is that? Presently Raymond Chandler’s wife’s “face had been plaster, but the flesh whitened it further.” A misprint for “flash” is indicated. Soon Thomas Mann, “a mustached man of about seventy,” doubling in this respect for his photographer, looks at his “pocked watch.” That should be “pocket watch,” but Mr. Theroux can write in such a manner that you hesitate to make up your mind.

Where the novel does well is in its sketching of the art, cult, and history of photography. Fox Talbot is remembered, Julia Cameron is revered, the American virtuosi of the twentieth century are paraded and disparaged: I was sorry there was no homage to the best of all photographers, Lartigue. You feel that the pictures credited to Maude would have been worth taking. Though the novelist overdoes the shame of a Florida banquet where businessmen are diverted by Arbus freaks and bare bareback riders from a local circus, the Pig Dinner shots come to life in the mind, as do her South Yarmouth Madonna, her Cuba pictures, her rogues’ gallery of eminent writers. Meanwhile the cliches of the Camera Club—“Honest Face,” “Drunken Bum,” “Prostitute in Slit Skit Standing near Rooms Sign“—provide a very funny page.

The novel presents an egomaniac in a darkroom meditating on the impersonality of art and holding that “subject is everything.” It tries to show that Maude’s exhibited, retrospective pictures fail to express that other subject which calls the shots, and that the secrets locked in the shots no one knows affirm her true self, and the failure of its loving endeavors. The book’s account of the proximity between these two failures, however, is unable to convey that the art for which she is known does not display her, and that the undisplayed incest picture does. The importance assigned to this emblem of Maude Pratt’s romantic agony is the most conventional, the least idiosyncratic, element in the book. Perhaps there is another thing that could be said about its sources, about the matter of convention. Picture Palace is a romantic fable which has history in it, and living people, and it may be that it also has in it a reading of Doctorow’s Ragtime.

According to Susan Sontag, photography in America has dealt with democracy in America, and has danced to Whitman’s tune. Picture Palace leaves the same impression. Whitman did not doubt “there is far more in trivialities, insects, vulgar persons, slaves, dwarfs, weeds, rejected refuse, than I have supposed.” Some of these subjects—vulgar persons, slaves, dwarfs—are Maude’s, and Maude is, in this sense, a patriot. Miss Sontag writes:

Like Whitman, Stieglitz saw no contradiction between making art an instrument of identification with the community and aggrandizing the artist as a heroic, romantic, self-expressing ego.

Perhaps we might say that Paul Theroux has invented a photographer who is missing from her own exhibition, in which subject—America, and Anglo-America—is everything, who declares herself only in her secret shots, and who nevertheless queens it over her subjects and is the heroine of her emblems of commonness and community.

Advertisement

Across the bridge near the spot on the Charles River where Maude courts her brother in his boat proceed the dramatis personae of David Plante’s novel, in the course of one of its chapters. These persons are the family of the title, the French Canadian Francoeurs, Jim and Reena and their seven sons, who have driven up from the parish of Notre Dame de Lourdes in Providence, Rhode Island, to spend the day with their clever son at MIT. The second last of the sons is Daniel, literature’s sensitive adolescent, gripped by a devotion to his mother and yet anxious to take off. The action is studiously located in their Providence house and in a house they acquire in the country, by a lake. Jim is a tool-cutter who falls out with his union and is sacked. He falls out, too, with the smart son, and expels him from the family. A crisis gathers when Reena, in her fifties, breaks down, and Jim resists the shock treatment prescribed for her.

At another point, it is said of some bathers, as in the Theroux, “You’re out too far,” and the idea is picked up again after Reena’s breakdown. At Boston College in 1958, Daniel receives a letter from his mother:

He didn’t know where he was, but he knew he was looking at the handwriting of someone very far in space, very far in time, as if she had died. He was startled. He had not been home in a month and a half, perhaps to show that he was independent. Now, suddenly, his independence, which he had forced on himself all the time he was away, detached him not only from his family, his mother and father, his brothers, but detached him from the time and place he was in. He felt that he had been so cut off from his mother he would never be able to see or speak or write to her again. He needed to get in touch with her right away. He wanted to reassure her that he wasn’t independent, and didn’t want to be independent.

Both of them are far out, in their different fashions. In the final passage of the novel, Daniel utters a prayer which may, or may not, stand in ironic relation to what has gone before, when the reader has been made aware that a sinister and dreary Catholic Church is part of their trouble:

To all these, in their strange high country, in their large bright house, pray for the small dark house in this low country.

The idea of being far out is present here as well, with religion promising a remoteness from the ordinary life of some low country.

The novel is preoccupied with space and place, with real and imaginary zones and countries, with the immediate and the remote, with the displacement of soul from body. This tendency is assisted by a painterly care for lights and colors, and it can look like a version of the nouveau roman’s early exactitude in depicting physical environments, determined as that was by a certain suspicion of feeling. The depiction of feeling, of mental states, is placed under restraint here, and is usually reserved for direct speech, for the terse English speech of bilingual puritans.

It may be that austerity imitates austerity in this book. Providence’s French Canadian enclave is a dark house, a hard and limited life, and it may be that the writing says so by means of the limits which it observes. Those who suspect an intrusion of theory in the book might admit that, in general, it is theory which fits the facts. But there are times when it interferes with them, when we are offered, for instance, a Daniel who appears to be what he is not—backward, unfeeling.

Again, the grim leanness of the narrative prose may be thought to defer to a community in which pleasure is an ice-cream soda and the occasional family farting match. Puritans and petomanes. (Frank Fusco publicly farts in the Theroux. What is happening up there in Massachusetts? Lover’s heartburn?) There’s a passage in which, with each in his own automobile, Jim meets and omits to greet his son Edmond, who has been away. Jim tells him to “back up.” “Edmond reversed, and saw his father back in his car, drive by.” The second “back” jars with the first, and the sentence is mispunctuated: noticing this, however, we may decide that the meager, grudging English here is imitative. The next paragraph opens: “His mother, too, wasn’t surprised to see him.” But neither Jim nor the author has spoken the so many words that might have expressed his father’s lack of surprise. The writer’s reliance on the tacit, on omission and ellipse, appears to copy a community in which taciturnity is repression. It is a method which has its dangers, but it has to be said that it does not do much damage on the whole, and that Edmond’s sense of exclusion from the family is among the most moving features of a moving novel.

A saw lops off the tip of Jim’s index finger: a telling image for what there is of loss, and of coercion and admonition, in the life of his community, and of his family, which both resists and reproduces that community. He does not complain or consult a doctor. He bears it. And his stoicism encourages one to guess about the ethnic properties of Mr. Plante’s stoical literary style. Jim’s forbearance suggests the Red Indian blood in him, which puts up with cruelty and inflicts it, while Mr. Plante’s suggests, among other things, a knowledge of the literature of France. There have been rules in both quarters which favor silence and reserve, and there have been rules in French literature to the effect that characters, but not authors, may speak their mind. There are pages of The Family which taste of Robbe-Grillet, whose opinions have been laid at Mr. Plante’s door, and of Racine, with his dramas of confinement and fault, and which also taste of the Iroquois. David Plante is writing about the world of his youth, and it is a world which can be seen to have supplied both method and material. This is a highly indigenous book, one which is not remote from its native ground.

It gets better as it goes on. Abstentions and exclusions matter less, and feeling achieves a thaw. The book is as solemn as its subject, but one or two of its finest effects, eventually, are effects of humor. The son André makes up as Madame Butterfly, causing no expressions of surprise whatever. At a late stage, Daniel is told by his mother about a letter from his brother Philip, in reply to a letter from their father, in which relations with Philip were severed. Jim has torn Philip’s letter up, and Reena says, speaking like a book, or like the translation of a book:

“I’ve tried to put it together to read it. I can’t. What does picayune mean?”

“I don’t know,” Daniel said.

“Philip wrote on one bit that his father’s action in writing his letter to him was picayune. You know Philip’s anger. Will you look it up for me?”

Jim had written that “the next time Philip sees him he’ll be in a pine box.” Daniel and Reena are amused by these words.

When Reena breaks down, her state is observed in terms of physical behavior, in terms of an itinerary from room to room, which begins:

The mother got up, walked to the open double doorway between the living room and the dining room, stopped and stood there, her back to her sons. She walked on to the doorway between the dining room and the kitchen, again stopped, and after a moment turned round and grasped the jamb on either side of her.

This is impressive. It is even, in its way, Phèdre. This, in its silent way, is Reena’s great speech. She is a prey, and she wishes to die. At the same time, the passage reminds the reader of less impressive itineraries in the novel, and it is as well that it is succeeded by revealing exchanges between Daniel and his impassioned mother.

Reena may be suffering a menopausal anguish: it is an anguish, at any rate, in which the wants and submissions of her life hit her as they haven’t done before, but in which she feels she has to yield to her husband, whose authority and severity and isolation have conditioned her grief. Shaken by the catastrophe, the sons blame their father for his stubbornness over the shock therapy—wrongly, we may be meant to think—and blame their mother for breaking down: one of them cries that the mother of a Marine should stand on her feet. They are all decent people who are helplessly at fault.

It is to these scenes that the drama in the novel moves, and if the drama is powerful, it is because the novel is truthful. Whether its literary doctrines are true (as well as appropriate) is another question. The book has some tedium in it, some dull moments, and these are due, not to its material, but to its method: writers with a special respect for lists, locations, and itineraries are apt to forget the difficulties readers have in responding to, or even taking in, the writing that comes of this. But it is also apparent that the method contributes to the drama of the book, that it joins in communicating the tragedy of Reena.

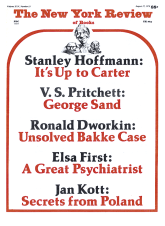

This Issue

August 17, 1978