Anyone interested in Brahmanic religious philosophy and Vedic verse meters, as well as in ancient music, should read this book. Another, incidental, subject is that of international drug culture, for Samavedic chanting, in its ritualistic form, takes place uniquely during sacrificial ceremonies in which libations of the juice of the soma plant are offered to the deities.

In the 1960s, Western audiences became more aware of Indian music, thanks in large measure to such virtuoso sitarists as Ravi Shankar, who influenced the Beatles and jazz figures like John Coltrane, and, in small measure, to the discovery of a parallel in the strictness of note-order between some ragas and twelve-tone series. Instrumental improvisation is simpler to appreciate, however, at least on one level, than a species of chanting that cannot even be exported from one jungle village to another. Furthermore, correspondences exist between ragas and Western music, both functionally, in the seasons and times of day at which a piece is performed (the church’s canonical hours), and in structure and content: one raga scale is identical with a Western mode, and ragas are harmonic in that the solo instrument forms two-note chords with the accompanying drone part (tala).

None of this is to suggest that a true comprehension of this infinitely subtle art form is imminent in the West, but merely to say that, compared to Samavedic chant, the raga is as close to us as Tchaikovsky. Yet in spite of the remoteness of thirty centuries, a vestige of the power of this venerable singing, and of the presence of the past—the Kauthuma notational numerals are believed to relate to the cries of animals—can be felt by wholly uninstructed listeners.

Some readers may wonder why Mr. Howard has devoted more than a third of his book to transcriptions, since the chants have come down to us by oral tradition. The Rgveda, for instance, the oldest of the Vedic collections, containing over 10,000 verses in more than 1,000 hymns, has been preserved practically unchanged for more than 3,000 years—written texts are about 900 years old—a scarcely believable phenomenon to the Hebrew, Christian, and Moslem who lives by his Book. The answer is that the music can be studied only through transcriptions, even though these are transposed (to facilitate legibility), merely approximate even in relative pitch, and convey nothing of the qualities of sound. In Mr. Howard’s book the transcriptions are in a far from calligraphic, not to say shaky, hand, and the notation of rhythmic values is unnecessarily dense: since long notes are rare, they could have been represented by halves, instead of quarters, thereby reducing the beams from four, the most common kind, to three.

At whatever the increase in the price of this already expensive book (“Thank you Paine Webber”), audio-visual cassettes should have been packaged with it, especially since the Vedic priests employ hand and finger positions (mudra) while intoning the ritual chants (sotras). One hopes that Mr. Howard’s tape recordings will soon be made available commercially. Besides enlightening us, they will encourage support for the study of the chants (and of Dravidian languages)—at the University of Mysore, to name only one center concerned with the continuation of this oldest of still-living musical arts.

A suggestion: read the glossary as an introduction, though at first only a few terms, such as “matras” (temporal units) and “Parrans” (the divisions of the chant, each sung in one breath), need be remembered.

Wagner’s “Rienzi” reveals more of the genesis of a Wagner opera than any other book on the composer in English—except that the quotations from his writings, and a twenty-two-page draft of the libretto, have been left in German. Briefly, Mr. Deathridge demonstrates that, in Rienzi at least, Wagner thought of himself as a dramatist first, a musician second, extensively rewriting the text but leaving no written evidence that he took many pains with the development of his musical ideas. This may mean no more than that he felt greater confidence in his musical than in his literary gifts, yet it is surprising that only two musical notations, one of them in Rienzi, are found in the prose drafts for all of his operas!

Wagner and Rienzi is a subject of general historical interest, since the opera supposedly inspired the young Hitler’s worship of the composer. In any case, Hitler acquired the 800-page original manuscript, and it was apparently with him when he died, no trace of it having been found. That Cola Rienzi, the fascist prototype, attracted both the composer and the dictator is not astonishing, but Der Führer’s fondness for the opera demolishes any claims for his musical discrimination. Rienzi is banal, inflated, and poverty-stricken in the quality of its musical ideas. To turn from Mr. Deathridge’s absorbing reconstruction of the dramatic plan of the full work to the opera itself is to disappoint even the least optimistic expectations.

Advertisement

On the day following the first performance (1842) of the seemingly endless score, Wagner marked a number of cuts. But its success with the audience had been so great that the principal singers protested, and Rienzi remained intact but unpublished, the composer soon disassociating himself from it. After his death, Cosima Wagner, with the help of her Bayreuth protégé Julius Kniese, tried to revise the opera according to the master’s later philosophy of the music drama, omitting, in the process, everything thought not to be absolutely essential to the action, including entire choruses, repetitions of words, and even musical ornaments. The first published score (1898-1899) was falsely advertised as “based on” the original, but this had not been made available, and Rienzi as Wagner conceived it disappeared in the “Götter-dämmerung” as Hitler staged it.

The cast in the new East German recording (Angel, SEXT 3818) is stunning, hence the stilted vocal style and the extended passages in extremely high registers are less of a torture to the ears than they might have been. Mercifully, the performance is abundantly cut.

This book contains fair appraisals (i.e., in agreement with the reviewer’s) of the strengths and weaknesses of Bruckner’s music, as well as clear identifications of the composer’s stylistic fingerprints: the unisons, octave leaps, homemade chorale tunes; the attraction to the mediant; the preference for brass instruments, both singly and massed (Wagner called him “the trumpet”). But the modern aspect of Bruckner’s rhythmic constructions, such as the simultaneous 3’s and 2’s, 4’s and 3’s, in the Adagio of the Fifth Symphony, is overlooked. These anticipate the Webern of Das Augenlicht, as do the coupling of themes with their inversions, and the use of silences.

The biographical chapters are less satisfactory. Bruckner’s “complexes” and intermittent insanity demand a Freudian “life,” or one by specialists in numeromania (the compulsive counting of everything, even the leaves on a tree), in hopeless infatuations with teenage girls (Olga the waitress, Ida the chambermaid, the Lolita to whom the unsuitably old bachelor daily brought flowers), and in the obsession, whether necrophilous or archaeological, with cadavers, skulls, mortal remains.

Now that Serge Lifar has reported the existence of another major sketchbook for the music of the ballet, Professor Forte’s guide to its chord structure may already be in need of updating. Before revisions are begun, however, his tables of the score’s harmonic vocabulary should be rechecked. In the simplest category—that of chords with only four different pitches—three out of nine musical examples, one of them the famous final chord, do not match the description in Table 1.

Professor Forte regards the Rite as essentially “atonal,” earlier analysts as essentially tonal. Boulez, for one, assumed an underlying tonic, dominant, and subdominant structure, and referred to chords in terms of triads with “appoggiaturas.” And undoubtedly much of the harmony of The Rite of Spring has a triadic character in spite of extraneous pitches.

But the Boulez approach was limited; it could not explain the more complex constructions, and, more important, the logic of their relations. For these reasons Professor Forte’s system, with its larger scope, supersedes those analyses based on the principles of classical harmony. The chapters on the Introduction to Part Two and on the Sacrificial Dance are particularly valuable.

That Couperin’s L’Apothéose de Lully and Richard Strauss’s Lully arrangements in Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme are better known than any music by Lully in its original form indicates the present neglect of the “founder of French opera.” Except for a few volumes reprinted from Henri Prunières’s Oeuvres Complètes (Paris, 1930-1939), which is not a performing edition, Lully’s music is virtually unavailable. Moreover, of the handful of pieces that have been recorded, none of the performances shows an understanding of proper rhythmic execution and of the realization of agréments.

These musicological standards are not improved in two new releases, one of Plaude, Laetere Gallia (Nonesuch, H-71039), the motet for the baptism of the Dauphin, the other of the Te Deum (Erato, STU 70927), yet they manage to suggest something of Lully’s stature. The most affecting music is in the Te Deum, in the solo quartet “Te ergo,” with its suspensions and falling thirds, and in duets momentarily reminiscent of Monteverdi. The choral and instrumental tutti—or “tous,” as Lully wrote, disdaining his native tongue—are Handelian in pomp, if not in majesty.

R.H.F. Scott’s Jean-Baptiste Lully, the first biography of the composer in English, devotes as much space to his pederasty as to his music, and, by a generous selection of the ribald rhymes he inspired, contributes as much to the history of buggery as to that of opera:

Advertisement

Un jour l’Amour dlt à sa mère

Pourquoi ne suis-je pas vêtu?

Si Baptiste me voit tout nu

C’en est fait de mon derrière.

In lieu of a discussion of the music, or even of the eight comédies-ballets that Lully wrote with Molière, Mr. Scott repeats anecdotes, some of them surely apocryphal, about the composer’s quarrels with the likes of Boileau and La Fontaine. The Te Deum is not presented as an example of the stile concertato, but used merely to retell the story of the composer’s death, for though he danced in his ballets, sometimes with the Sun King as a partner, corybantic conducting was not yet in fashion, and, keeping time during a performance of the Te Deum by tapping the floor with a stick, Lully accidentally struck his foot and died from the injury.

Comprehensive but concise, sound in its musical analyses, Michael Talbot’s Vivaldi may well become the popular English-language “life and works” for a decade—and possibly for longer than that if the subject were another composer. Vivaldi is still being discovered, however, and unknown scores, such as the trio-sonata recently come to light in Dresden, are certain to appear. Peter Ryom’s Les Manuscrits de Vivaldi (Copenhagen, 1977), a monument to leg, library, and mental work, describes hundreds of autograph scores, sometimes with the aid of ultraviolet screening, but the reader is far from convinced that the last aria, sinfonia, opera fragment has been found, and that the problems of attribution, authenticity, and self-borrowing or contrafacta can soon be solved.

Vivaldi the man emerges in Mr. Talbot’s pages in a fuller dimension than in other biographies, partly because of his perceptive reinterpretations of writings by such contemporaries as Goldoni, De Brosses, and Benedetto Marcello. Only a few years ago, the dates of the composer’s birth and death were matters of conjecture, but these, and much more, have been established from recent research, primarily in Venice and Vienna.

The remarkable feature of Mr. Talbot’s survey of the music of the “Red Priest” is that the vocal works, scarcely mentioned in earlier monographs, receive almost as much space as the instrumental. But since Vivaldi’s contemporaries admired his concertos more than his operas, the posthumous neglect of the latter was predictable. Unsure of himself in his first stage works, he sometimes gave the most important melodic lines to the orchestra, and to some extent his development as an opera composer can be measured in the increasing independence of his vocal from his instrumental style. Apart from these considerations, the reader is not left with a compelling desire to learn the operas. Of the sixteen out of forty-five that survive complete, all suffer from dramatic diffuseness and a lack of structural variety in the individual numbers. Mr. Talbot believes that one factor in the superiority of Vivaldi’s sacred over his secular vocal music is that the liturgical texts do not permit excessive use of the da capo form. In any event, the staging of the operas today may pose insuperable obstacles.

Other features of the book are a brief history of the effect of the shift in music publishing early in the eighteenth century from Venice to Amsterdam and the North; precise descriptions of instruments (earlier writers failed not only to identify the salmò as a chalumeau, for instance, but even to distinguish recorders and transverse flutes); and some judicious comments on Bach’s transcriptions of Vivaldi. Although these last enriched the music contrapuntally, “a streak of pedantry sometimes made [Bach] gild the lily,” and he added or subtracted measures “to produce a symmetry more characteristic of his own music than of Vivaldi’s.” An example in music-type shows Bach missing the point of a sequence in the finale of Concerto RV 580.

Some of Mr. Talbot’s statements are peculiar. Thus, while establishing the dates of the Mantuan period, he writes that

if Vicenzo [sic] di Gonzaga had lost Monteverdi to Venice…the recruitment of Caldara [to Mantua]…showed that the pull could as well come from the other direction.

But a more unequal exchange would be difficult to imagine. Also, the finale of Concerto RV 159 is characterized as “frankly experimental,” a “collage…of two thematically self-contained movements—one of a three-part concertino…the other for a four-part ripieno…[a] crazy quilt of a form.” So far from a “crazy quilt,” the music, all in one tempo, is a simple dialogue, and the solo trio and full string groups take regular turns. Instead of an “experiment,” the piece is an expression of the Venetian tradition of antiphony.

“There is nothing I long for more intensely…than to be taken for a better sort of Tchaikovsky,” Arnold Schoenberg wrote in 1947, “or…that people should know my tunes and whistle them.” This condescension would be shocking if these ambitions were not so totally unreal: Schoenberg is not likely to be taken for any sort of Tchaikovsky, and no “tune” by the founder of serial composition shows the slightest promise of entering the repertory of whistlers. Yet it is the overplayed Russian, rather than the neglected Viennese, who is in need of just appreciation.

Tchaikovsky is the only composer of the late nineteenth century to have contributed enduring works in every branch of his art—opera and ballet, symphony and concerto, chamber and piano music, vocal music both sacred and secular. Admittedly the distance between his best and his worst is immense, but the worst does not count, except that in his case it is the chief obstacle, together with the popularity, to a fair appraisal of his music. Thus the famous movement in the first quartet obscures its other, more accomplished ones; the crashing-cymbal finales drown out the instrumental genius; and the repetitive and bombastic symphonic developments tend to conceal the great miniaturist of the ballets.

Mr. Warrack’s survey of the man and his music offers some reappraisals, including a higher place for the Manfred Symphony. He is a fair-minded critic who tries to defend Nikolai Rubinstein’s rejection of the B-flat minor Concerto by the academic criteria of the time, and because of supposed weaknesses in form and construction. The reader is not persuaded. Rubinstein, who was one of the founders of the Moscow Conservatory, where Tchaikovsky taught, should have been able to perceive the originality, and that it outweighed the faults.

Mr. Warrack adopts another perplexing critical attitude, regretting that “Tchaikovsky’s inspiration was Delibes, whom…he preferred to Wagner as a composer.” Without Delibes, however, The Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty might not have been written, whereas a Wagnerian Tchaikovsky is too horrible to contemplate. Perhaps for the reason that Tchaikovsky was not a harmonic innovator, Mr. Warrack gives no examples in music-type—David Brown’s book contains nearly one hundred of them—but his verbal descriptions of themes might better have been omitted as well, especially the anthropopathic kind:

…a single melodic phrase that attempts to heave itself up painfully and on its second statement is forced to collapse back onto the original note….

Mr. Warrack believes that too little is known about “Tchaikovsky’s psychology” and the “causes of homosexuality” to attribute his “subsequent disposition to any definite origin,” though this was surely a result, at least in part, of his mother’s dominating affection, her tragic death, and the child’s untransferable love for her. In any event, all editions of Tchaikovsky’s letters are still expurgated, since Soviet scholars both acknowledge his homosexuality and ignore it, regarding such subjects as his identification with Tatiana and his artistic exhibitionism and selfpity as suitable only for the bourgeois non-science of psychopathology.

The book’s photographs of the composer in his male entourage reveal more than the text, which does not even consider that his patron Mme von Meck may have broken with Tchaikovsky because stories of his profligacy had reached her ears. Tchaikovsky’s affairs with youths in Florence, Tiflis, and elsewhere were not well-kept secrets, and even in St. Petersburg and Moscow scandals involving blackmail must have been known. It was following an encounter with a woman who demanded money because of his relationship with her son that Tchaikovsky drank the fatal glass of unboiled water.

The first installment of David Brown’s three-volume study contains the most thorough discussion in English of the first two symphonies, the early operas, Romeo and Juliet, and much other, especially little-known, music. Concerning the B-flat minor Concerto, Mr. Brown ably refutes Rubinstein’s argument as presented by Mr. Warrack on the so-called shortcomings of the piece. Mr. Brown also gives an excellent account of Tchaikovsky’s years as a civil servant, apprentice-composer, and music critic, as well as a study of the influence of Balakirev.

The second volume will begin with the composition of Swan Lake and presumably its centerpieces will be studies of Eugene Onegin and the Fourth Symphony, which is the turning point in Tchaikovsky’s career much as the Eroica was in Beethoven’s. The later books are eagerly awaited, but it is to be hoped that Mr. Brown’s prose improves, and that he does not include references to “passages that would once have moistened the tear ducts.” As he tells it, when the composer declared that some day he would make his brother Nikolay proud, the latter “never forgot his…look, nor the tone of voice in which these words were uttered”—which sounds less appropriate in a work of scholarship than in a boys’ weekly—a weekly for “good boys,” of course. Mr. Brown goes on to say that “for some years whenever [Tchaikovsky] was conducting he would clutch his chin with his left hand to hold his head in place….” Mr. Warrack says that this happened only once. But however frequent the occurrence, what the reader wonders is: who turned the pages?

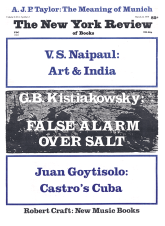

This Issue

March 22, 1979